Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain

| Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain | |

|---|---|

| Pohqui Moosie | |

|

Poke-O-Moonshine, with cliffs, from U.S. Route 9 to the north | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,180 ft (660 m) [1] |

| Prominence | 299 ft (91 m) |

| Parent peak | Old Rang Mountain |

| Coordinates | 44°24′6″N 73°30′47″W / 44.40167°N 73.51306°WCoordinates: 44°24′6″N 73°30′47″W / 44.40167°N 73.51306°W |

| Geography | |

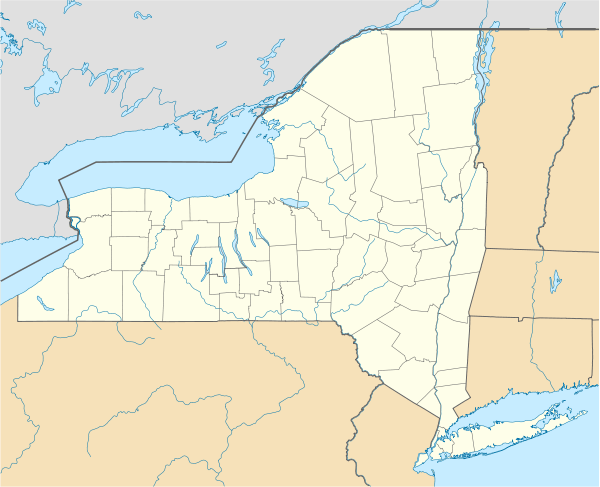

Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain Map showing location of mountain within New York | |

| Location | New York, U.S. |

| Parent range | Adirondacks |

| Topo map | Au Sable Forks |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Old jeep road, trail |

Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain, spelled Pokamoonshine on U.S. Geological Survey maps, and sometimes known as just Poke-O, is a minor peak of the Adirondack Mountains. The name is believed to be a corruption of the Algonquin words pohqui, meaning 'broken', and moosie, meaning 'smooth'.[2] It is located in the town of Chesterfield, New York, United States, on New York state Forest Preserve land, part of the Taylor Pond Wild Forest complex within the Adirondack Park. Due to its location next to the pass through which most travelers from the north enter the range, it has been called the "gateway to the Adirondacks".

At its 2,180-foot (660 m) summit is a disused fire lookout tower listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While many of those who reach it and take in the sweeping views of the High Peaks and Lake Champlain hike up one of two trails from U.S. Route 9 near the mountain's base, the stone cliffs ringing its summit have attracted climbers, although their activities are limited during the nesting season of the peregrine falcon. Its easy access from the Adirondack Northway (Interstate 87) and challenging routes have made it the most popular rock and ice climbing spot in the Adirondacks,[3] regularly drawing visitors from both the U.S. and Canada.

Geography

Poke-O-Moonshine is located at the eastern end of a group of summits at the northeastern corner of the Adirondacks. Most of the peaks to its west are of similar height, though lower; Old Rang Mountain a mile (1.6 km) to the northwest is higher at 2,294 feet (699 m). To the east is a pass roughly 500 feet (150 m) wide, traversed by Interstate 87, locally referred to as the Adirondack Northway, and U.S. Route 9. Across it rises a similar unnamed peak with several summits, the highest of which reaches 1,620 feet (490 m).[4]

It is located in the southern portion of the town of Chesterfield, near its tripoint with the towns of Lewis and Willsboro. The nearest settlements are the central hamlet of Willsboro to the east-southeast and the village of Keeseville to the north-northeast. Both are approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) from the mountain.[4] A ridge connects the mountain to Carl Mountain a mile to the west. On the mountain's east and south, the slopes rise steeply from the pass to the granite cliffs, their main scarp face 600 feet (180 m) high and a mile wide,[5] that bracket the summit and the northeast ridge. The north side has a gentler, but deeper, drop into the valley of McGuire Brook, which drains into Butternut Pond to the north and then, via that body's outlet into Augur Lake, to the AuSable River. On the south, a steeper drainage goes to Cold Brook, which flows into the North Branch of the Boquet River. Both streams themselves drain into Lake Champlain, whose Willsboro Bay is 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Poke-O-Moonshine's summit.[4]

History

Humans have lived in the Adirondacks since at least the end of the Wisconsin glaciation, 10-12,000 years ago. In the 11th century, farming began in the surrounding river valleys, which led many inhabitants to come down from the mountains.[6] The Algonquin, the first humans known to have lived in the area of the mountain, were as struck by its cliffs as later visitors. They named the mountain for them—Pohquis Moosie, in their language, roughly translates to "place of the broken smooth rocks." It was important to them since it stood aside the pass that allowed access to the mountains from the plains next to the lake, and thus became a frequent location for trade and diplomatic meetings between their tribes.[1]

Because of the area's remoteness from settlements established during the 17th century by the British and Dutch to the south and the French to the north, European settlers did not come to the area in significant numbers. Since it was vacant, the land was claimed during the 18th century by both the British, who had conquered New Netherland, and the French. King George's War in mid-century failed to settle that claim, and it took the later French and Indian War to establish British hegemony over all the European colonies in the region. Settlement was further delayed by the Revolutionary War, and only afterwards, with the new state of New York owning the land, was it subdivided and sold to veterans.[6] Those first settlers corrupted the Algonquin name to "Poke-O-Moonshine."[7]

The 200-acre (81 ha) lot that includes the mountain's summit reverted to state ownership following a tax sale in 1876.[7] During his lengthy survey of the Adirondacks, Verplanck Colvin used Poke-O-Moonshine's summit as his Station #26, establishing the benchmark that remains today. A high wooden tower was built near it to assist in the survey.[8]

In 1885, the state legislature created the Forest Preserve in response to fears that silt eroding from heavily logged slopes in the Adirondacks would render the Erie Canal unnavigable and adversely affect the state's economy. It required that any state land in certain areas, including Essex County, "be forever kept as wild forest lands." A decade later, this was added to the New York State Constitution as Article XIV.[9]

In the first decade of the 20th century, droughts led to series of devastating wildfires in the Adirondacks. New York's Forest, Fish and Game Commission (FFGC), a predecessor land-management agency to today's Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), decided to follow Maine's example and build fire lookouts on strategically located mountains throughout the range.[10] In 1912 a trail was cut and a wooden tower built atop Poke-O-Moonshine; five years later the current metal tower replaced it.[7]

The FFGC, now the Conservation Commission, added other facilities such as a cabin and springhouse during the 1920s. In 1928 writer Walter Collins O'Kane commended the view of Lake Champlain and Vermont from the tower in his Trails and Summits of the Adirondacks. The mountain became a popular hike.[7] In 1940 a guidebook produced by the Federal Writers' Project also endorsed that view, and reported a local legend that the peak's name had acquired a second meaning during Prohibition, when the pass became a popular place to distill and sell illegal liquor to loggers working in camps deeper in the mountains.[11]

In 1930 the state built a 25-site campground on three acres (1.2 ha) next to Route 9. It began purchasing additional land on and around the mountain the following year. This would eventually prove beneficial to another group of outdoor enthusiasts.[12]

Since the development of technical mountaineering equipment in the early 20th century, climbers had been attempting the many rock cliffs and walls of the Adirondacks. However, this effort had been hampered by the lack of quality roads in the sparsely populated region and the difficulty they posed in getting even to trailheads for those cliffs. In the late 1950s this situation had improved somewhat, and Geoff Smith and John Turner began making many first ascents of many of those cliffs.[13] They particularly concentrated on Poke-O-Moonshine, with Turner's bold (for the time) style allowing him to name and rate many of its routes.[3]

Throughout the rest of the 20th century the hikers and climbers kept coming, aided by the completion of the Northway in the late 1960s. The state continued to buy land when it was available. Better methods of fire detection became available, and the risks of fire declined to the point that DEC closed the fire tower in 1988. Three years later, the observer's cabin was burned down; only the fireplace and foundation remain.[7]

In 1995 DEC announced it was planning to dismantle the fire tower. As with many of the state's other historic fire towers, a local organization was formed to raise the funds to save it. It was renovated and reopened three years later.[7]

By 2004 the state had acquired 272 additional undeveloped acres (110 ha) for the campground and brought its mountain holdings to 2,082 acres (843 ha).[12] Five years later, however, during a budget crisis, the campground was shut down due to low use,[14] although it remains open as a day-use access area to the cliffs.[12]

In 2011, another access route was added when the Adirondack Land Trust bought the 200 acres (81 ha) to the south, allowing the jeep road to the summit to be converted into a trail. It was longer, but less steep, than the existing trail.[15] In 2013 another private organization's purchase added to the protected land around the mountain, when the Open Space Institute bought a conservation easement on 1,356 acres (549 ha) to the north. The land, which extended all the way to Butternut Pond, is not on the mountain itself but within its northern viewshed.[16]

Geology

The Adirondacks, geologically, are distinct from all other mountains in New York. While the Catskills, Taconics and other chains are in different ways part of the Appalachian Mountains, the northern mountains are a southerly extension of the Laurentian Mountains in the Canadian province of Québec. The Adirondack range is a large dome that uplifted and began to erode before being shaped further by geologically recent glacial epochs. It is often referred to as "new mountains from old rock" due to the pre-Cambrian nature of most of the rock and the relatively recent orogeny.[17]

Poke-O-Moonshine's massif is thus a miniature version of the range as a whole. Its bedrock is the same granite–gneiss combination as the rest of the range.[5] The climbing cliffs feature subtypes of that rock like ferrodiorite and lamprophyre.[2] There are some sheets of Potsdam Sandstone on the mountain, relics of a time before the orogeny when the land was beneath a shallow sea.[18]

Natural environment

The slopes of the mountain are covered in a northern hardwood forest similar to that found throughout the Adirondacks at lower elevations. The dominant species are sugar maple, birch and beech. There are a few oaks, a species not found much in the Adirondack forests, at lower elevations. Herbaceous plants in the understory include many fern species, and sarsaparilla.[19]

Higher up, where the slopes become rockier near and around the cliffs, other tree species, like white pine, striped maple and hemlock show up in the forest. Stinging nettles grow in the understory, along with red-flowering raspberry and wildflower species like trillium.[19]

On the summit ridge, the trees grow shorter and scrubbier. Mountain ash joins the forest. The summit's altitude is too low, even at its latitude, for the boreal forest found at higher elevations in the Adirondacks to flourish.[19]

The mountain's forest supports a diverse array of wildlife typical of the region. It is most notable for the peregrine falcons that nest in the cliffs. Since they are considered an endangered species in New York, DEC usually closes climbing routes that go near known nesting sites at the beginning of the climbing season in the springtime, sometimes till after midsummer, until all the falcons known to have hatched have successfully fledged.[20] The department works closely with the climbing community on this, since the nesting falcons have been known to attack humans who come too close.[20] Birders come to Poke-O-Moonshine during those times to watch the falcons, as well as the ravens that also nest there.[21]

Access

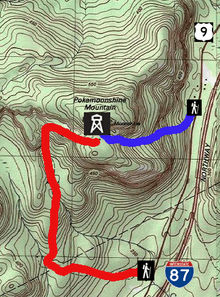

Two trails lead to the summit of Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain. Both meet at the site of the observer's cabin on the south promontory below the upper cliffs; from there it is a short climb to the fire tower. The Upper Tiers lean-to is located a short distance away from their junction.

Ranger's Trail

From the south end of the old campground, the Ranger's Trail ascends under the cliff bases. First it traverses the slopes to the south, then attacks the slope more directly as it bends to the west. Unofficial side trails serving climbers go to the foot and, later, the tops of the cliffs. On a promontory roughly 2,000 feet (610 m) in elevation, it meets the Observer's Trail at the site where the cabin once stood. From there it turns north to the summit.[4]

For a long time the Ranger's Trail was the only public route to the top. The campground served as its trailhead, and thus it is still heavily used by climbers since it provides access to the base of the cliffs via unofficial side trails. It is only 1.2 miles (1.9 km) to the summit, but it climbs 1,280 feet (390 m) in that distance, giving much of the trail a steep grade averaging 35% .[22]

In addition to its steepness, it suffers from some of the same common problems as older Adirondack trails. It is heavily eroded in some areas; water runs along some stretches in spring and after significant rainfall. As part of the fire tower restoration, it was marked with 11 interpretive stations pointing hikers' attention to natural history in the surroundings, discussed in detail in a brochure available at the trailhead.[23]

Observer's Trail

The Adirondack Land Trust's 2008 purchase of 200 acres (81 ha) south of the mountain allowed the former jeep road to be cleared and used as a trail. Two years later it was opened as the Observer's Trail. Its trailhead is almost a mile south of the Ranger's trailhead along Route 9, just past Cold Brook, over the Lewis town line. It is longer, at 2.4 miles (3.9 km), and adds more vertical, requiring a 1,450-foot (440 m) climb to the summit. However, as a result, its grade is much gentler. It passes two beaver ponds on the way up to the junction with the Ranger's Trail.[15]

From its trailhead lot it crosses right over the brook, then heads west while ascending gently for a half-mile (1 km). At a ridgeline 1,100 feet (340 m) in elevation, it turns to the north. At first it follows the ridge, then descends slightly into the wetlands surrounding the beaver ponds, in the headwaters of the brook. It climbs again and then turns back east, where it meets the Ranger's Trail at the cabin ruin after a thousand feet (300 m).[4]

Summit

The summit of Poke-O-Moonshine is a small open area of rock. The firetower is located at its north, leaving a wide ledge. From it there is expansive view of the valley to the south of the mountain, with the Northway running through it. Further in that direction the Adirondack High Peaks stand out, with Giant and, further to the southwest, Whiteface mountain, distinguished by its prominent ski trails. Southeast the narrower south end of Lake Champlain is visible.[19]

From the firetower views open up in all directions. North of the mountain the Adirondacks yield to the plains and farmland of Clinton County and the lake opens up; Plattsburgh is visible, and in clear enough weather even Montréal, across the Canada–US border in Québec. East of Poke-O-Moonshine Burlington, Vermont, is visible across the lake, and beyond it the Green Mountains of that state.[19]

Climbing

Poke-O-Moonshine is considered the Adirondacks' best climbing location.[3] Its cliffs were first climbed by John Turner, an English immigrant to Canada, and a group of others from the Montréal area, during the late 1950s and early 1960s.[24] Another group of regular climbers from Plattsburgh consolidated the work of Turner's group through the rest of the decade while trying to keep awareness of the mountain from being disseminated too widely, lest the cliffs become as busy on the weekends as those of the Shawangunk Ridge farther south and closer to New York City. By the mid-1970s, however, Poke-O-Moonshine had become known throughout the climbing community of the Northeast, yet without crowds developing.[25] Today, on a busy weekend, the climbers are likely to be a mixture of Americans and French Canadians.[2]

The cliffs are divided into three main areas: the Main Wall across the north and east face of the mountain, easily visible when approaching from the north; the Slab, the rock face seen first when approaching from the south; and the Upper Tiers, the cliffs around the summit.[26] Many of the routes available are highly challenging, with grades in the higher levels of the Yosemite Decimal System. Climbers with less skill than that required for such climbs are advised to avoid those routes or just hike up the mountain.[27]

Routes range from the 5.4 Snake at the easier end[28] to 5.13 Salad Days, a 100-foot (30 m) pitch described as "the hardest climbing yet done in the Adirondacks."[29] Both are on the Main Wall. Catharsis, a five-pitch 450-foot (140 m) 5.5 route on the Slab, has long been the mountain's most popular.[30]

On the Main Wall are other popular routes: Remembering Youth (5.12),[31] the 500-foot (150 m), five-pitch Gamesmanship (5.8) and Southern Hospitality (5.11)[32] FM, another climber favorite rated 5.8 over five pitches and 400-foot (120 m) of the Main Wall, got its name during its first ascent when one of John Turner's associates screamed "Fuck me!" after a rock he stepped on broke loose.[33] Positive Thinking, a 5.9 elsewhere on the wall, has become Poke-O-Moonshine's most popular ice route,[34] despite a 2003 accident in which a Canadian climber fell to his death after the ice he was on detached.[35]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Poke-O-Moonshine". Summitpost.org. 2000–2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Grant, James W. (September 2, 2009). "Lower Peaks, And Lighter Traffic". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Lewis, S. Peter; Horowitz, David (2003). Selected Climbs in the Northeast: Rock, Alpine, and Ice Routes from the Gunks to Acadia. Seattle: The Mountaineers Books. pp. 104–114. ISBN 9780898868579. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Au Sable Forks Quadrangle – New York – Clinton, Essex Cos. (Map). 1:24,000. USGS 7½ x 15' map series. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 Toula, Tim (2002). Rock 'n' Road: An Atlas of North American Rock Climbing Areas. Globe Pequot. pp. 275–276. ISBN 9780762723065. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 "Taylor Pond Management Complex – Draft Unit Management Plan – May 2012" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. May 2012. pp. 5–6. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Draft UMP, 8–9.

- ↑ Wes Haynes (May 2000). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain Fire Observation Station". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ "History of the Adirondack Park". Adirondack Park Agency. 2003. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ Podskosch, Martin (2000). Fire Towers of the Catskills: Their History and Lore. Fleischmanns, New York: Purple Mountain Press. p. 14. ISBN 1-930098-10-3.

- ↑ New York City Guide. Federal Writers Project. 1940. p. 556. ISBN 9781623760311. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Draft UMP, 3–4.

- ↑ Fast, Yvona (April 22, 2010). "Geoffrey Smith: Rock climbing and ski pioneer". Adirondack Daily Enterprise. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ Blaise, Lucas (February 23, 2009). "DEC Closes Poke-O-Moonshine Campground for 2009 season". Press-Republican. Plattsburgh, NY. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- 1 2 Gregory, Alan (July 3, 2011). "New trail eases hike up gateway to Adirondacks". Standard-Speaker. Hazleton, PA. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Easement protects land near Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain". Adirondack Daily Enterprise. January 28, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Richard, Glenn A. (2007). "Old Rocks and New Mountains: Natural History of the Adirondacks" (PowerPoint presentation). State University of New York at Stony Brook. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Richard, slide 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ostertag, Rhonda and George (2002). Hiking New York (2nd ed.). Gloeb Pequot. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9780762722426. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- 1 2 "Adirondack Rock Climbing Route Closures". July 20, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Brown, Phil (1999). Longstreet Highroad Guide to the Adirondacks. Boulder, CO: Taylor Trade Publications. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9781563525056. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Marshall, Ash (Fall 2003). "A Small Pleasure, Poke-O-Moonshine Stands Tall". All Points North. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ↑ Draft UMP, 48/

- ↑ Mellor, Don (1995). Climbing in the Adirondacks: A Guide to Rock and Ice Routes in the Adirondack Park (3rd ed.). Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club. p. 29. ISBN 0-935272-79-8.

- ↑ Mellor, 31.

- ↑ Mellor, 213.

- ↑ Hoekstra, David (2007). Frommer's Best RV and Tent Campgrounds in the U.S.A. John Wiley & Sons. p. 588. ISBN 9780470069295. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ↑ Mellor, 231.

- ↑ Mellor, 237.

- ↑ Mellor, 223–224.

- ↑ Mellor, 233–234.

- ↑ Mellor, 254–255.

- ↑ Mellor, 240–242.

- ↑ Mellor, 250.

- ↑ Williamson, Jed (2004). Accidents in North American Mountaineering 2003. The Mountaineers Books. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780930410940. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain. |

- Poke-O-Moonshine Mountain at Summitpost.org