Playfair cipher

The Playfair cipher or Playfair square or Wheatstone-Playfair cipher or Wheatstone cipher is a manual symmetric encryption technique and was the first literal digram substitution cipher. The scheme was invented in 1854 by Charles Wheatstone, but bears the name of Lord Playfair who promoted the use of the cipher.

The technique encrypts pairs of letters (bigrams or digrams), instead of single letters as in the simple substitution cipher and rather more complex Vigenère cipher systems then in use. The Playfair is thus significantly harder to break since the frequency analysis used for simple substitution ciphers does not work with it. The frequency analysis of bigrams is possible, but considerably more difficult. With 600[1] possible bigrams rather than the 26 possible monograms (single symbols, usually letters in this context), a considerably larger cipher text is required in order to be useful.

History

It became known as the Playfair cipher after Lord Playfair, who heavily promoted its use, despite its invention by Wheatstone. The first recorded description of the Playfair cipher was in a document signed by Wheatstone on 26 March 1854.

It was rejected by the British Foreign Office when it was developed because of its perceived complexity. Wheatstone offered to demonstrate that three out of four boys in a nearby school could learn to use it in 15 minutes, but the Under Secretary of the Foreign Office responded, "That is very possible, but you could never teach it to attachés."

It was used for tactical purposes by British forces in the Second Boer War and in World War I and for the same purpose by the British and Australians during World War II. This was because Playfair is reasonably fast to use and requires no special equipment - just a pencil and some paper. A typical scenario for Playfair use was to protect important but non-critical secrets during actual combat e.g. the fact that an artillery barrage of smoke shells would commence within 30 minutes to cover soldiers' advance towards the next objective. By the time enemy cryptanalysts could decode such messages hours later, such information would be useless to them because it was no longer relevant.

During the Second World War, the Government of New Zealand used it for communication among New Zealand, the Chatham Islands, and the coastwatchers in the Pacific Islands.[2][3]

Superseded

Playfair is no longer used by military forces because of the advent of digital encryption devices. This cipher is now regarded as insecure for any purpose, because modern computers could easily break it within seconds.

The first published solution of the Playfair cipher was described in a 19-page pamphlet by Lieutenant Joseph O. Mauborgne, published in 1914.[4]

Description

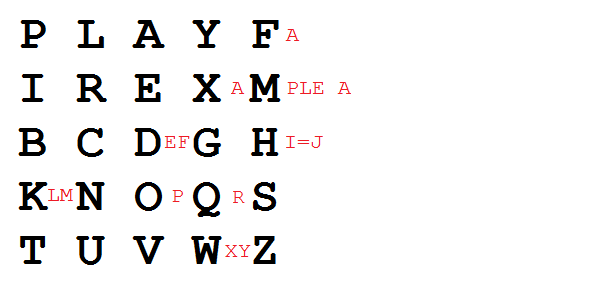

The Playfair cipher uses a 5 by 5 table containing a key word or phrase. Memorization of the keyword and 4 simple rules was all that was required to create the 5 by 5 table and use the cipher.

To generate the key table, one would first fill in the spaces in the table with the letters of the keyword (dropping any duplicate letters), then fill the remaining spaces with the rest of the letters of the alphabet in order (usually omitting "Q" to reduce the alphabet to fit; other versions put both "I" and "J" in the same space). The key can be written in the top rows of the table, from left to right, or in some other pattern, such as a spiral beginning in the upper-left-hand corner and ending in the center. The keyword together with the conventions for filling in the 5 by 5 table constitute the cipher key.

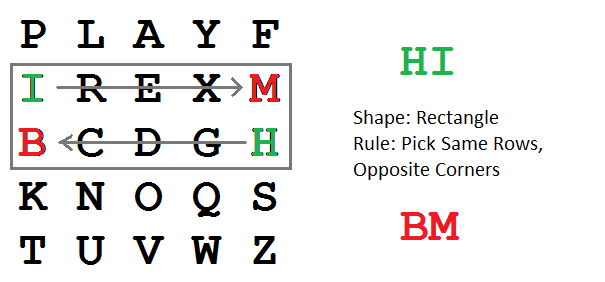

To encrypt a message, one would break the message into digrams (groups of 2 letters) such that, for example, "HelloWorld" becomes "HE LL OW OR LD", and map them out on the key table. If needed, append an uncommon monogram to complete the final digram. The two letters of the digram are considered as the opposite corners of a rectangle in the key table. Note the relative position of the corners of this rectangle. Then apply the following 4 rules, in order, to each pair of letters in the plaintext:

- If both letters are the same (or only one letter is left), add an "X" after the first letter. Encrypt the new pair and continue. Some variants of Playfair use "Q" instead of "X", but any letter, itself uncommon as a repeated pair, will do.

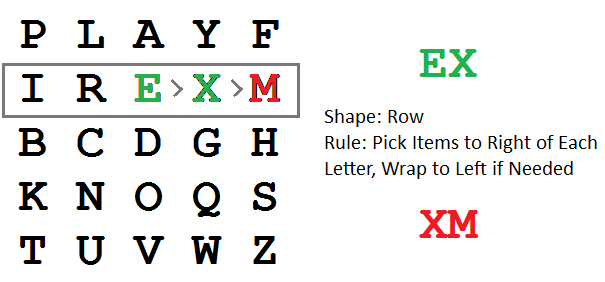

- If the letters appear on the same row of your table, replace them with the letters to their immediate right respectively (wrapping around to the left side of the row if a letter in the original pair was on the right side of the row).

- If the letters appear on the same column of your table, replace them with the letters immediately below respectively (wrapping around to the top side of the column if a letter in the original pair was on the bottom side of the column).

- If the letters are not on the same row or column, replace them with the letters on the same row respectively but at the other pair of corners of the rectangle defined by the original pair. The order is important – the first letter of the encrypted pair is the one that lies on the same row as the first letter of the plaintext pair.

To decrypt, use the INVERSE (opposite) of the last 3 rules, and the 1st as-is (dropping any extra "X"s, or "Q"s that do not make sense in the final message when finished).

There are several minor variations of the original Playfair cipher.[5]

Example

Using "playfair example" as the key (assuming that I and J are interchangeable), the table becomes (omitted letters in red):

P L A Y F I R E X M B C D G H K N O Q S T U V W Z

Encrypting the message "Hide the gold in the tree stump" (note the null "X" used to separate the repeated "E"s) :

HI DE TH EG OL DI NT HE TR EX ES TU MP

^

| 1. The pair HI forms a rectangle, replace it with BM |  |

| 2. The pair DE is in a column, replace it with OD |  |

| 3. The pair TH forms a rectangle, replace it with ZB |  |

| 4. The pair EG forms a rectangle, replace it with XD |  |

| 5. The pair OL forms a rectangle, replace it with NA |  |

| 6. The pair DI forms a rectangle, replace it with BE | |

| 7. The pair NT forms a rectangle, replace it with KU | |

| 8. The pair HE forms a rectangle, replace it with DM | |

| 9. The pair TR forms a rectangle, replace it with UI | |

| 10. The pair EX (X inserted to split EE) is in a row, replace it with XM |  |

| 11. The pair ES forms a rectangle, replace it with MO | |

| 12. The pair TU is in a row, replace it with UV | |

| 13. The pair MP forms a rectangle, replace it with IF |

BM OD ZB XD NA BE KU DM UI XM MO UV IF

Thus the message "Hide the gold in the tree stump" becomes "BMODZ BXDNA BEKUD MUIXM MOUVI F". (Breaks included for ease of reading the cipher text.)

Clarification with picture

Assume one wants to encrypt the digram OR. There are five general cases:

1)

* * * * * * O Y R Z * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Hence, OR → YZ |

2)

* * O * * * * B * * * * * * * * * R * * * * Y * * Hence, OR → BY |

3)

Z * * O * * * * * * * * * * * R * * X * * * * * * Hence, OR → ZX |

4)

* * * * * * * * * * * O R C * * * * * * * * * * * Hence, OR → RC |

5)

* * * * * * * R * * * * O * * * * I * * * * * * * Hence, OR → IO |

Cryptanalysis

Like most classical ciphers, the Playfair cipher can be easily cracked if there is enough text. Obtaining the key is relatively straightforward if both plaintext and ciphertext are known. When only the ciphertext is known, brute force cryptanalysis of the cipher involves searching through the key space for matches between the frequency of occurrence of digrams (pairs of letters) and the known frequency of occurrence of digrams in the assumed language of the original message.[6]

Cryptanalysis of Playfair is similar to that of four-square and two-square ciphers, though the relative simplicity of the Playfair system makes identifying candidate plaintext strings easier. Most notably, a Playfair digraph and its reverse (e.g. AB and BA) will decrypt to the same letter pattern in the plaintext (e.g. RE and ER). In English, there are many words which contain these reversed digraphs such as REceivER and DEpartED. Identifying nearby reversed digraphs in the ciphertext and matching the pattern to a list of known plaintext words containing the pattern is an easy way to generate possible plaintext strings with which to begin constructing the key.

A different approach to tackling a Playfair cipher is the shotgun hill climbing method. This starts with a random square of letters. Then minor changes are introduced (i.e. switching letters, rows, or reflecting the entire square) to see if the candidate plaintext is more like standard plaintext than before the change (perhaps by comparing the digrams to a known frequency chart). If the new square is deemed to be an improvement, then it is adopted and then further mutated to find an even better candidate. Eventually, the plaintext or something very close is found to achieve a maximal score by whatever grading method is chosen. This is obviously beyond the range of typical human patience, but computers can adopt this algorithm to crack Playfair ciphers with a relatively small amount of text.

Another aspect of Playfair that separates it from four-square and two-square ciphers is the fact that it will never contain a double-letter digram, e.g. EE. If there are no double letter digrams in the ciphertext and the length of the message is long enough to make this statistically significant, it is very likely that the method of encryption is Playfair.

A good tutorial on reconstructing the key for a Playfair cipher can be found in chapter 7, "Solution to Polygraphic Substitution Systems," of Field Manual 34-40-2, produced by the United States Army. Another cryptanalysis of a Playfair cipher can be found in Chapter XXI of Helen Fouché Gaines, Cryptanalysis / a study of ciphers and their solutions.[7]

A detailed cryptanalysis of Playfair is undertaken in chapter 28 of Dorothy L. Sayers' mystery novel Have His Carcase. In this story, a Playfair message is demonstrated to be cryptographically weak, as the detective is able to solve for the entire key making only a few guesses as to the formatting of the message (in this case, that the message starts with the name of a city and then a date). Sayers' book includes a detailed description of the mechanics of Playfair encryption, as well as a step-by-step account of manual cryptanalysis.

The German Army, Air Force and Police used the Double Playfair system as a medium-grade cipher in WWII, but as they had broken the cipher early in WWI, they adapted it by introducing a second square from which the second letter of each bigram was selected, and dispensed with the keyword, placing the letters in random order. But with the German fondness for pro forma messages, they were broken at Bletchley Park. Messages were preceded by a sequential number, and numbers were spelled out. As the German numbers 1 (eins) to twelve (zwölf) contain all but eight of the letters in the Double Playfair squares, pro forma traffic was relatively easy to break (Smith, page 74-75)

Modern comparisons

Computer-run block ciphers work in a manner similar to Playfair’s: they break the original message into blocks of characters and apply a complex mathematical transformation, based upon the key, to each of those blocks.

Naturally, modern ciphers are not restricted to upper-case, no-punctuation, J-less messages. Any form of data that can be stored on a computer can be encrypted with a modern cipher.

A modern block cipher can be run in a mode similar to that of Playfair, where the same block (in Playfair, a pair of letters) always encrypts to the same bit of ciphertext: in our example, CO will always come out as OW. Indeed, many poorly written encryption programs use just this technique, called Electronic Codebook, or ECB.[8]

More sophisticated implementation of a cipher will use one of many other modes. The most common is called Cipher Feedback Mode, or CFB.

CFB starts by encrypting something other than the message. This bit at the front of things is called an initialization vector, or IV. The IV need not be secret, but the same IV should never be re-used with the same encryption key.

First, encrypt the IV. Take the IV and combine it with the first block of the plaintext. With computers, this is done with a mathematical function called a binary XOR; a similar effect could be accomplished with Playfair by "adding" the two together: C + H = K; W + F = B. It is this value which is written to the ciphertext.

Next, take the result from the last step, encrypt it as normally, and add it to the next block from the plaintext. In this way, the encryption of each block depends upon the encryption of each preceding block.

Encrypt IV -> XOR (add) result with first block of plaintext -> write as ciphertext -> encrypt from previous -> XOR with next block of plaintext -> write as ciphertext -> repeat

The example encoded with Playfair modified in this way, using an IV of "AB" might look thus:

OKHKBGVF…

This process greatly increases the security of the encryption system. When done with computers, the speed of the processing of the encryption is not significantly hindered.

Use in modern crosswords

Advanced thematic cryptic crosswords like The Listener Crossword (published in the Saturday edition of the British newspaper The Times) occasionally incorporate Playfair ciphers.[9] Normally between 4 and 6 answers have to be entered into the grid in code, and the Playfair keyphrase is thematically significant to the final solution.

The cipher lends itself well to crossword puzzles, because the plaintext is found by solving one set of clues, while the ciphertext is found by solving others. Solvers can then construct the key table by pairing the digrams (it is sometimes possible to guess the keyword, but never necessary).

Use of the Playfair cipher is generally explained as part of the preamble to the crossword. This levels the playing field for those solvers who have not come across the cipher previously. But the way the cipher is used is always the same. The 25-letter alphabet used always contains Q and has I and J coinciding. The key table is always filled row by row.

In popular culture

- The novel Have His Carcase by Dorothy L. Sayers gives a blow-by-blow account of the cracking of a Playfair cipher.

- The World War 2 thriller The Trojan Horse by Hammond Innes conceals the formula for a new high-strength metal alloy using the Playfair cipher.

- In the film National Treasure: Book of Secrets, a treasure hunt clue is encoded as Playfair cipher.

- In the audio book Rogue Angel : God of Thunder, a Playfair cipher clue is used to send Anja Creed to Venice.

See also

Notes

- ↑ No duplicate letters are allowed, and one letter is omitted (Q) or combined (I/J), so the calculation is 600 = 25×24.

- ↑ "A History of Communications Security in New Zealand By Eric Mogon", Chapter 8

- ↑ "The History of Information Assurance (IA)". Government Communications Security Bureau. New Zealand Government. Retrieved 2011-12-24.

- ↑ Mauborgne, Joseph Oswald, An Advanced Problem in Cryptography and Its Solution (Fort Leavenwoth, Kansas: Army Service Schools Press, 1914).

- ↑ Gaines 1956, p. 201

- ↑ Gaines 1956, p. 201

- ↑ Gaines 1956, pp. 198–207

- ↑ Electronic codebook

- ↑ Listener crossword database

References

- Gaines, Helen Fouché (1956) [1939], Cryptanalysis / a study of ciphers and their solutions, Dover, ISBN 0-486-20097-3

- Smith, Michael Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998, Channel 4 Books/Macmillan, London) ISBN 0-7522-2189-2

External links

- Online encrypting and decrypting Playfair with JavaScript

- Extract from some lecture notes on ciphers – Digraphic Ciphers: Playfair

- Playfair Cypher

- Cross platform implementation of Playfair cipher