Pensions crisis

The pensions crisis is a predicted difficulty in paying for corporate, state, and federal pensions in the United States and Europe, due to a difference between pension obligations and the resources set aside to fund them. Shifting demographics are causing a lower ratio of workers per retiree; contributing factors include retirees living longer (increasing the relative number of retirees), and lower birth rates (decreasing the relative number of workers, especially relative to the Post-WW2 Baby Boom). There is significant debate regarding the magnitude and importance of the problem, as well as the solutions.[1]

For example, as of 2008, the estimates for the underfunding of the United States state pension programs range from $1 trillion using the discount rate of 8% to $3.23 trillion using U.S. Treasury bond yields as the discount rate.[2][3] The present value of unfunded obligations under Social Security as of August 2010 was approximately $5.4 trillion. In other words, this amount would have to be set aside today such that the principal and interest would cover the program's shortfall between tax revenues and payouts over the next 75 years.[4]

Some economists question the concept of funding, and, therefore underfunding. Storing funds by governments, in the form of fiat currencies, is the functional equivalent of storing a collection of their own IOUs. They will be equally inflationary to newly written ones when they do come to be used.[5]

Reform ideas are in three primary categories: a) Addressing the worker-retiree ratio, via raising the retirement age, employment policy and immigration policy; b) Reducing obligations via shifting from defined benefit to defined contribution pension types and reducing future payment amounts (by, for example, adjusting the formula that determines the level of benefits); and c) Increasing resources to fund pensions via increasing contribution rates and raising taxes.

Background

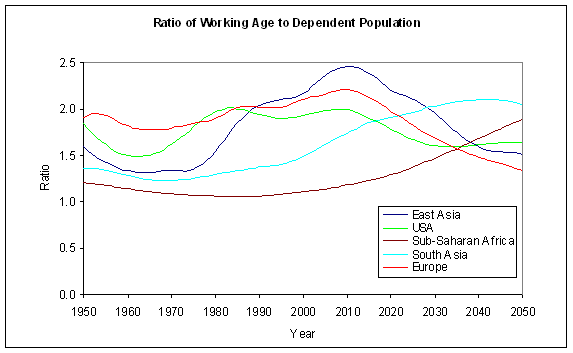

The ratio of workers to pensioners (the "support ratio") is declining in much of the developed world. This is due to two demographic factors: increased life expectancy coupled with a fixed retirement age, and a decrease in the fertility rate. Increased life expectancy (with fixed retirement age) increases the number of retirees at any time, since individuals are retired for a longer fraction of their lives, while decreases in the fertility rate decrease the number of workers.

In 1950, there were 7.2 people aged 20–64 for every person of 65 or over in the OECD countries. By 1980, the support ratio dropped to 5.1 and by 2010 it was 4.1. It is projected to reach just 2.1 by 2050. The average ratio for the EU was 3.5 in 2010 and is projected to reach 1.8 by 2050.[6] Examples of support ratios for selected countries in 1970, 2010, and projected for 2050:[1]

| Country | 1970 | 2010 | 2050 (projected) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 5.3 | | 4.5 | | 2.6 | |

| Japan | 8.5 | | 2.6 | | 1.2 | |

| Britain | 4.3 | | 3.6 | | 2.4 | |

| Germany | 4.1 | | 3.0 | | 1.6 | |

| France | 4.2 | | 3.5 | | 1.9 | |

| Netherlands | 5.3 | | 4.0 | | 2.1 | |

Pension computations

Pension computations are often performed by actuaries using assumptions regarding current and future demographics, life expectancy, investment returns, levels of contributions or taxation, and payouts to beneficiaries, among other variables. One area of contention relates to the expected investment return rate. If this rate (expressed as a percentage) is increased, relatively lower contributions are demanded of those paying into the system. Critics have argued that investment return percentage rate assumptions are artificially inflated, to reduce the required contribution amounts by individuals and governments paying into the pension system. For example, the U.S. stock market (adjusted for inflation) did not have a sustained increase in value between 2000 and 2010. However, many pensions have annual investment return assumptions or estimates in the 7–8% range, which are closer to the pre-2000 average return. If these rates were lowered 1–2 percentage points, the required pension contributions taken from salaries or via taxation would increase dramatically. By one estimate, each 1 point reduction means 10% more in contributions. For example, if a pension program reduced its investment return rate assumption from 8% to 7%, a person contributing $100 per month to their pension would be required to contribute $110. Attempting to sustain better-than-market returns can also cause portfolio managers to take on more risk.[7]

The International Monetary Fund reported in April 2012 that developed countries may be underestimating the impact of longevity on their public and private pension calculations. The IMF estimated that if individuals live three years longer than expected, the incremental costs could approach 50% of 2010 GDP in advanced economies and 25% in emerging economies. In the United States, this would represent a 9% increase in pension obligations. The IMF recommendations included raising the retirement age commensurate with life expectancy.[8]

United States

U.S. Social Security program

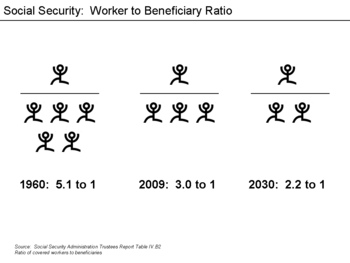

The number of U.S. workers per retiree was 5.1 in 1960; this declined to 3.0 in 2009 and is projected to decline to 2.1 by 2030.[9] The number of Social Security program recipients is expected to increase from 44 million in 2010 to 73 million in 2030.[10] The present value of unfunded obligations under Social Security as of August 2010 was approximately $5.4 trillion. In other words, this amount would have to be set aside today such that the principal and interest would cover the shortfall over the next 75 years.[4] The Social Security Administration projects that an increase in payroll taxes equivalent to 1.9% of the payroll tax base or 0.7% of GDP would be necessary to put the Social Security program in fiscal balance for the next 75 years. Over an infinite time horizon, these shortfalls average 3.4% of the payroll tax base and 1.2% of GDP.[11]

U.S. State-level issues

In financial terms, the crisis represents the gap between the amount of promised benefits and the resources set aside to pay for them. For example, many U.S. states have underfunded pensions, meaning the state has not contributed the amount estimated to be necessary to pay future obligations to retired workers. The Pew Center on the States reported in February 2010 that states have underfunded their pensions by nearly $1 trillion as of 2008, representing the gap between the $2.35 trillion states had set aside to pay for employees' retirement benefits and the $3.35 trillion price tag of those promises.[2]

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) reported in January 2011 that:

- As of 2010, the state pension shortfall ranges between $700 billion and $3 trillion, depending on the discount rate used to value the future obligations. The $700 billion figure is based on using a discount rate in the 8% range representative of historical pension fund investment returns, while the $3 trillion represents a discount rate in the 5% range representative of historical Treasury bond ("risk-free") yields.[12]

- This shortfall emerged after the year 2000, substantially due to tax revenue declines from two recessions.

- States contribute approximately 3.8% of their operating budgets to their pension programs on average. This would have to be raised to 5.0% to cover the $700 billion shortfall and around 9.0% to cover the $3 trillion shortfall.

- Certain states (e.g., Illinois, California, and New Jersey) have significantly underfunded their pension plans and would have to raise contributions towards 7–9% of their operating budgets, even under the more aggressive 8% discount rate assumption.

- States have significant time before the pension assets are exhausted. Sufficient funds are present already to pay obligations for the next 15–20 years, as many began funding their pensions back in the 1970s. The CBPP estimates that states have up to 30 years to address their pension shortfalls.

- States accumulated more than $3 trillion in assets between 1980 and 2007 and there is reason to assume they can and will do that again, as the economy recovers.

- Nearly all debt issued by a state (generally via bonds) is used to fund its capital budget, not its operating budget. Capital budgets are used for infrastructure like roads, bridges and schools. Operating budgets pay pensions, salaries, rent, etc. So state debt levels related to bond issuance and the funding of pension obligations have substantially remained separate issues up to this point.

- State debt levels have ranged between 12% and 18% of GDP between 1979 and 2009. During the second quarter of 2010, the debt level was 16.7%.

- State interest expenses remains a "modest" 4%-5% of all state/local spending.

- Pension promises are contractually binding. In many states, constitutional amendments are also required to modify them.[13]

The pension replacement rate, or percentage of a worker's pre-retirement income that the pension replaces, varies widely from state to state. It bears little correlation to the percentage of state workers who are covered by a collective bargaining agreement. For example, the replacement rate in Missouri is 55.4%, while in New York it is 77.1%. In Colorado, replacement rates are higher but these employees are barred from participating in Social Security.[14]

The Congressional Budget Office reported in May 2011 that "most state and local pension plans probably will have sufficient assets, earnings, and contributions to pay scheduled benefits for a number of years and thus will not need to address their funding shortfalls immediately. But they will probably have to do so eventually, and the longer they wait, the larger those shortfalls could become. Most of the additional funding needed to cover pension liabilities is likely to take the form of higher government contributions and therefore will require higher taxes or reduced government services for residents".[15]

U.S. city and municipality pensions

In addition to states, U.S. cities and municipalities also have pension programs. There are 220 state pension plans and approximately 3,200 locally administered plans. By one measure, the unfunded liabilities for these programs are as high as $574 billion. The term unfunded liability represents the amount of money that would have to be set aside today such that interest and principal would cover the gap between program cash inflows and outflows over a long period of time. On average, pensions consume nearly 20 percent of municipal budgets. But if trends continue, over half of every dollar in tax revenue would go to pensions, and by some estimates in some instances up to 75 percent.[16][17]

As of early 2013, several U.S. cities had filed for bankruptcy protection under federal laws and were seeking to reduce their pension obligations. In some cases, this might contradict state laws, leading to a set of constitutional questions that might be addressed by the U.S. Supreme Court.[18]

Shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions

The Social Security Administration reported in 2009 that there is a long-term trend of pensions switching from defined benefit (DB) (i.e., a lifetime annuity typically based on years of service and final salary) to defined contribution (DC) (e.g., 401(k) plans, where the worker invests a certain amount, often with a match from the employer, and can access the money upon retirement or under special conditions.) The report concluded that: "On balance, there would be more losers than winners and average family incomes would decline. The decline in family income is expected to be much larger for last-wave boomers born from 1961 to 1965 than for first-wave boomers born from 1946 to 1950, because last-wave boomers are more likely to have their DB pensions frozen with relatively little job tenure."[19]

The percentage of workers covered by a traditional defined benefit (DB) pension plan declined steadily from 38% in 1980 to 20% in 2008. In contrast, the percentage of workers covered by a defined contribution (DC) pension plan has been increasing over time. From 1980 through 2008, the proportion of private wage and salary workers participating in only DC pension plans increased from 8% to 31%. Most of the shift has been the private sector, which few changes in the public sector. Some experts expect that most private-sector plans will be frozen in the next few years and eventually terminated. Under the typical DB plan freeze, current participants will receive retirement benefits based on their accruals up to the date of the freeze, but will not accumulate any additional benefits; new employees will not be covered. Instead, employers will either establish new DC plans or increase contributions to existing DC plans.[19]

Employees in unions are more likely to be covered by a defined benefit plan, with 67% of union workers covered by such a plan during 2011 versus 13% of non-union workers.[20]

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in November 2013: "Today, however, workers who have any retirement plan at all generally have defined-contribution plans—basically, 401(k)'s—in which employers put money into a tax-sheltered account that's supposed to end up big enough to retire on. The trouble is that at this point it's clear that the shift to 401(k)'s was a gigantic failure. Employers took advantage of the switch to surreptitiously cut benefits; investment returns have been far lower than workers were told to expect; and, to be fair, many people haven't managed their money wisely. As a result, we're looking at a looming retirement crisis, with tens of millions of Americans facing a sharp decline in living standards at the end of their working lives. For many, the only thing protecting them from abject penury will be Social Security."[21][22]

A 2014 Gallup poll indicated that 21% of investors had either taken an early withdrawal of their 401(k) defined contribution retirement plan or a loan against it over the previous five years.[23] Fidelity Investments reported in February 2014 that:

- The average 401(k) balance reached a record $89,300 in the fourth quarter of 2013, a 15.5% increase over 2012 and almost double the low of $46,200 set in 2009 (which was affected by the Great Recession).

- The average balance for persons 55 and older was $165,200.

- Approximately one-third (35%) of all 401(k) participants cashed out their accounts when they left their jobs in 2013, which can cost investors in terms of penalties and taxes.[24]

Solutions

Reform ideas are in three primary categories: a) Addressing the worker-retiree ratio, via raising the retirement age, employment policy, and immigration policy; b) Reducing obligations via shifting from defined benefit to defined contribution pension types and reducing future payment amounts; and c) Increasing resources to fund pensions via increasing contribution rates and raising taxes. Recently the latter has included proposals for and actual confiscation of private pension plans and merging them into government run plans.[25]

Proposed solutions to the pensions crisis include ones that address the dependency ratio – later retirement, part-time work by the aged, encouraging higher birth rates, or immigration of working aged persons – and ones that take the dependency ratio as given and address the finances – higher taxes, reductions in benefits, or the encouragement or reform of private saving.

In the United States, since 1979 there has been a significant shift away from defined benefit plans with a corresponding increase in defined contribution plans, like the 401(k). In 1979, 62% of private sector employees with pension plans of some type were covered by defined benefit plans, with about 17% covered by defined contribution plans. By 2009, these had reversed to approximately 7% and 68%, respectively. As of 2011, governments were beginning to follow the private sector in this regard.[26]

Research indicates that employees save more if they are automatically enrolled in savings plans (i.e., enrolled and given an option to drop out, as opposed to being required to take action to opt into the plan). Some countries have laws that require employers to opt employees into defined contribution plans.[26]

Criticisms

Other sources of income

Some claim that the pensions crisis does not exist or is overstated, as pensioners in developed countries faced with population aging are often able to unlock considerable housing wealth and make returns from other investments or employment.

Demographic transition

Some argue (FAIR 2000) that the crisis is overstated, and for many regions there is no crisis, because the total dependency ratio – composed of aged and youth – is simply returning to long-term norms, but with more aged and fewer youth: looking only at aged dependency ratio is only one half of the coin. The dependency ratio is not increasing significantly, but rather its composition is changing.

In more detail: as a result of the demographic transition from "short-lived, high birth-rate" society to "long-lived, low birth-rate" society, there is a demographic window when an unusually high portion of the population is working age, because first death rate decreases, which increases the working age population, then birth rate decreases, reducing the youth dependency ratio, and only then does the aged population grow. The decreased death rate having little effect initially on the population of the aged (say, 60+) because there are relatively few near-aged (say, 50–60) who benefit from the fall in death rate, and significantly more near-working age (say, 10–20) who do. Once the aged population grows, the dependency ratio returns to approximately the same level it was prior to the transition.

Thus, by this argument, there is no pensions crisis, just the end of a temporary golden age, and added costs in pensions are recovered by savings in paying for youth.

However, if a country's fertility rate falls too far below replacement level, in future there will be unusually few workers supporting the still large retiree population, and the dependency ratio will rise above historical levels, possibly causing an actual crisis.

A complicating factor is that support for the youth and support for the aged may be provided by different agents, funded in different ways, making the hand off difficult. For example, in the United States, care for the youth is provided by parents, with the primary government expense being education, which is primarily provided by local and state governments, paid for by property taxes (a form of wealth tax), while care for the aged is commonly provided by hospitals and nursing homes, and the expenses are pensions and health care, which are provided by the federal government, paid for by payroll taxes (a form of income tax). Thus, local property taxes and the untaxed labor of parents cannot be directly handed off to fund pensions and health care, creating a coordination problem.

Key terms

- Support ratio: The number of people of working age compared with the number of people beyond retirement age

- Participation rate: The proportion of the population that is in the labor force

- Defined benefit: A pension linked to the employee's salary, where the risk falls on the employer to pay a contractual amount

- Defined contribution: A pension dependent on the amount contributed and related investment performance, where the risk falls mainly on the employee[1]

See also

- Criticisms of welfare

- Demographic window

- Dependency ratio

- Generational accounting

- Pension

- Public debt

- Retirement plan

- Social Security debate (United States)

- Social Security

- Sub-replacement fertility

References

- 1 2 3 The Economist-Falling Short-April 2011

- 1 2 Pew Center on the States-The Trillion Dollar Gap-February 2010

- ↑ http://rnm.simon.rochester.edu/research/JEP_Fall2009.pdf

- 1 2 2010 Social Security Trustees Report Tables VI.F1 and VI.F2

- ↑ Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds Of Economic Policy

- ↑ The Economist-Old Age Dependency Ratios-May 2009

- ↑ Reuters-James Saft-Pension Assumptions Hitting the Wall-January 2009

- ↑ IMF-Global Financial Stability Survey-April 2012

- ↑ Concord Slides

- ↑ The Economist-As Boomers Wrinkle-December 2010

- ↑ Trustees Report Long Range Estimates - Section 5a Table IV.B6

- ↑ Equicapita: Demographics are Still Destiny

- ↑ CBPP-Misunderstandings Regarding State Debt, Pensions, and Retiree Health Costs Create Unnecessary Alarm-January 2011

- ↑ New York Times-Mary Williams Walsh-The Burden of Pensions on States-March 2011

- ↑ CBO-The Underfunding of State and Local Pension Plans-May 2011

- ↑ The Atlantic-Anthony Flint-The Next Big Financial Crisis That Could Cripple Cities-September 2012

- ↑ The State of Local Government Pensions: A Preliminary Inquiry-Gordon, Rose and Fischer-July 2012

- ↑ NYT-Public Pensions In Bankruptcy Court-April 2013

- 1 2 Social Security Administration (March 2009). "The Disappearing Defined Benefit Pension". Social Security Administration. Retrieved May 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Bureau of Labor Statistics-William Wiatrowski-The Last Private Industry Pension Plans: A Visual Essay-December 2013

- ↑ NYT-Paul Krugman-Expanding Social Security-November 21, 2013

- ↑ EPI-Retirement Inequality Chartbook-Retrieved November 23, 2013

- ↑ Gallup Poll-401k Withdrawals-December 2014

- ↑ USA Today-Fidelity: Average 401k Doubles Since 2009

- ↑

- Jan Iwanik, European nations begin seizing private pensions, Christian Science Monitor, January 2, 2011.

- 1 2 Falling Short, The Economist, April 2011

- FAIR (September 2000), A Ponzi Problem: The U.S. Dependency Ratio, Social Security Solvency, and the False Panacea of Immigration

- Eisner, Robert (August 1997), The Great Deficit Scares, The Century Foundation

External links

- BBC (UK) pensions crisis articles

- C-SPAN Video Library: Search: Social Security crisis

- 2013 Social Security Trustees Report Jun 3, 2013: federal retirement program on a fiscally unsustainable long-term path without Congressional action

- Social Security and Retirement Costs Aug 2, 2013: Stephen Goss, Social Security Administration Chief Actuary, speaks on uncertainty of projections

- EPI-Retirement Inequality Chartbook

- Wiseman, Paul; McHugh, David; Kurtenbach, Elaine (December 28, 2013). "Unprepared: The world braces for retirement crisis". Associated Press, via The Boston Globe.