Penmachno

| Penmachno | |

Gethin Square, Penmachno, with the old corner shop |

|

Penmachno |

|

| OS grid reference | SH790505 |

|---|---|

| Community | Penmachno |

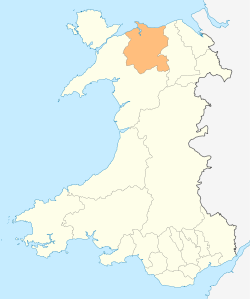

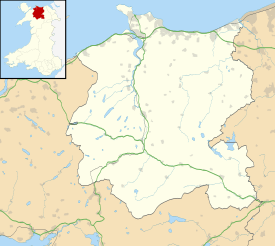

| Principal area | Conwy |

| Ceremonial county | Clwyd |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BETWS-Y-COED |

| Postcode district | LL24 |

| Dialling code | 01690 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| EU Parliament | Wales |

| UK Parliament | Aberconwy |

| Welsh Assembly | Aberconwy |

Coordinates: 53°02′17″N 3°48′14″W / 53.038°N 3.804°W

Penmachno is a village in the isolated upland valley of Cwm Penmachno, 4 miles south of Betws-y-Coed in the county of Conwy, north Wales. The two parts of the village are linked by a five-arched, stone bridge dating from 1785. The village has been referred to as Pennant Machno, Llandudclyd and Llan dutchyd in historical sources.[1][2]

According to the 2011 census, the population of the Bro Machno Parish (which also includes Cwm Penmachno) was 617, of whom 342 (55%) were able to speak Welsh and 214 (34%) had no skills in Welsh.[3]

Notable residents

It is renowned as the birthplace of Bishop William Morgan (probably 1545 – 1604), who was born at Tŷ Mawr, Y Wybrnant, near the village; the precise year of his birth is uncertain, it is generally accepted to be 1545, but his memorial in Cambridge suggests 1541.Memorial in St John's College Chapel, Cambridge He was one of the leading scholars of his day, having mastered Hebrew in addition to Latin and Greek. He was the first to translate the Bible in its entirety into Welsh. Tŷ Mawr is now a National Trust property open to the public and contains a Bible museum.[4]

_NLW3364544.jpg)

Owen Gethin Jones (1816 - 1883), a building contractor, poet prominent in Eisteddfod circles and local historian, was born on 1 May 1816 at Tyn-y-Cae, Penmachno, and died on 29 January 1883 at Tyddyn Cethin (as recorded in 1871 and 1881 Wales censuses and National Probate Calendar for 1883, but currently known as Tyddyn Gethin (English: Home of Gethin or Gethin House)), also in Penmachno, after being paralysed at the beginning of 1882.[5] He built the Rhiwbach Tramway serving the Blaenau Ffestiniog quarries, the Betws-y-Coed railway station and the Pont-y-Pant railway station, the Pont Gethin viaduct on the Conwy Valley Line[5][6][7] spanning the Lledr Valley and St Mary's Church, Betws-y-Coed.[8] His essay on Penmachno, written in the mid 19th century, was first published in 1884 (after his death) in ′Gweithiau Gethin′ (The Works of Gethin).[9] The essay refers to the first nonconformist sermon in the parish in about 1784 at Penrhyn Uchaf; it describes the buildings at Dugoed farm (53°03′11″N 3°46′55″W / 53.053°N 3.782°W) (the oldest part of the farmhouse was built around 1517[10]) and reflects on the possible sites of historical significance on the farm itself including Tomen y Castell as a possible fort and the field Cae'r Braint which means 'Field of Honour' that may have contained a great Bardic circle).[11]

Huw Owen alias Huw Machno (1585 - 1637), poet is recorded by Owen Gethin Jones as living at Coed-y-Ffynnon near Penmachno (53°03′40″N 3°47′10″W / 53.061°N 3.786°W). Gethin Jones writes in his essay:

| “ | Coed-y-Ffynnon, the old home of the learned and inspired Bard, Hugh Machno, who worked with... the famous Richard Cynwal. Their rank as Bards is seen in the Caerwys Eisteddfod - Hugh Machno was the winner in the Cywydd class for his ′Eulogy of Archbishop Williams′...[He] was educated at Cambridge and was one of the best debators of his day. It is said he died a batchelor and was buried in the churchyard where there used to be an oval lead plate hanging on the wall over his head to commemorate him but in one way or another, like many other things belonging to the second church it got lost.

and: He was buried in the churchyard and carved on his gravestone is 'H. Machno obiit 1637'. |

” | |

| — Owen Gethin Jones [9] pages 18 and 38 respectively | |||

A gravestone inscribed 'H. M. Obiit 1637' exists.[12][13] It is claimed that Huw Machno was descended from Dafydd Goch of Penmachno, an illegitimate son of Dafydd III (1238 - 1283, the last independent ruler of Wales as the Prince of Wales) and therefore a grandson of Llywelyn the Great.[14]

Richard Edgar Thomas (known as Richie Thomas) (1906 - 1988), the tenor, was born at Eirianfa, Llewelyn Street, Penmachno and lived his whole life in the village. He worked at the Machno Woollen Mill (Richie Thomas working at Woollen Mill) and led the singing in his chapel for over 50 years.[15] He first came to prominence when he won the Blue Riband at the Rhyl National Eisteddfod in 1953.[16] He gave many concerts and numerous recordings were made, and a double-album of his best work was released in 2008 under the title ′Richie Thomas - Goreuon Richie Thomas (Tenor)′. There is a plaque to commemorate him at his birthplace.[17]

Parish Church

The parish church of Saint Tudclud (alternatively Tyddyd, Tudclyd, Tudglud or Tudglyd),[1] although it was only built in the mid-nineteenth century,[18] contains five important, early Christian, inscribed stone slabs dating from the 5th or 6th century. The Carausius Stone, which bears the Chi Rho symbol, was found in 1856 with two of the others when the site of the church was being cleared.[19] It has been suggested that it is the grave stone of Carausius, a Roman military commander who usurped power in 286 and was assassinated in 293 (see Carausian Revolt),[20][21][22] who is possibly the same person as St Caron to whom the church in Tregaron is dedicated.[23] Another commemorates Cantiorix as a citizen of Gwynedd and cousin of the magistrate[24] (the local ruler under the Romans, suggesting that the Roman political structure was retained locally into the 5th century).[25][26] The third of these slabs reads "ORIA [H]IC IACIT" or "Oria lies here".[27] A fourth stone slab was discovered in the old garden wall of the Eagles Hotel (about 40 m from the church and 15 m from the churchyard) in 1915; one interpretation of its inscription is "...son of Avitorius... in the time of Justinus the Consul".[28] There was a consul called Justinus in 540, but the inscription is unclear and could refer to Justus (328); the broadest date range for the slab is 328 - 650. Several academics have recently suggested that the inscription refers to the Byzantine Emperor Justin II, who was consul repeatedly between 567 and 574; it is argued that this is one of a number of instances of close links between post-Roman Britain and the Byzantine Empire.[29] The fifth slab was discovered during quarrying near the Roman road in Rhiwbach, Cwm Penmachno and just features a cross.

The chancel of the present church stands on the site of a previous church which burnt down in 1713. Three of the stone slabs were discovered when the older church was dismantled. Also discovered was a wall of a 12th-century church; this was the church of St Enclydwyn (probably the same as St Clydwyn or Cledwyn, a 6th-century saint, the eldest son of Brychan Brycheiniog and brother of St Tudful), this church fell into ruin following the Reformation. The existing font is 12th-century and from the earliest church.[30] The discovery of the slabs on the site and the large enclosure of the church that is now the graveyard (about 100 m by 75 m), suggests there was a religious community here, probably a Clas. It has been suggested that Iorwerth ab Owain Gwynedd (1145-1174), also known as Iorwerth Drwyndwn, the father of Llywelyn the Great, was buried in the oldest church, and that a sixth stone slab in the present church (a 13th-century gravestone) marked his grave.[2][31]

The holy well of St Tudclud is in the cellar of the old Post Office, now a private dwelling.

Other significant associations

Penmachno briefly featured during the revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294–95 as the place at which Madog signed the so-called Penmachno Document, the only surviving direct evidence for the rebel leader's use of the title of Prince of Wales.

About 3 km northeast of Penmachno(53°03′36″N 3°46′55″W / 53.060°N 3.782°W), close to the disused 19th century, water-powered Machno Woollen Mill (Glandwr Factory[32] or Factory Isaf[33])(Inspecting a blanket made at the factory, 1952) built in 1839, there is a drystone-built, packhorse bridge over the Machno river. This is known as the 'Roman Bridge' but it is actually 16th or 17th century.[34] Penmachno is, however, near the section of the Sarn Helen Roman road from Betws-y-Coed to the Roman fort of Tomen y Mur near Trawsfynydd, this road became part of the Cistercian Way between Aberconwy Abbey and Cymer Abbey which also passed near Ysbyty Ifan.

A world-class mountain bike trail has been built on the nearby forested slopes. It consists of a 20 km loop with an optional 10 km extension.[35] There are limited car parking facilities on the site, however, and no visitor centre, as local residents believed increased visitor numbers would spoil village life.[36]

The village was used as a special stage in the 2013 Wales Rally GB.

Gallery

View from the Machno Hotel looking NW towards St Tudclud Church with the bridge in the foreground (about 1875)

View from the Machno Hotel looking NW towards St Tudclud Church with the bridge in the foreground (about 1875) View of Penmachno looking SW towards the Bethania Chapel (about 1875)

View of Penmachno looking SW towards the Bethania Chapel (about 1875) Betws-y-Coed Railway Station (built by Owen Gethin Jones)

Betws-y-Coed Railway Station (built by Owen Gethin Jones) Pont Gethin, Dolwyddelan (during construction in about 1875)

Pont Gethin, Dolwyddelan (during construction in about 1875) Tyddyn Cethin

Tyddyn Cethin St Tudclud Parish Church, Penmachno

St Tudclud Parish Church, Penmachno "Roman Bridge", Afon Machno

"Roman Bridge", Afon Machno Machno Woollen Mill

Machno Woollen Mill The Roman road between Betws-y-Coed and Penmachno

The Roman road between Betws-y-Coed and Penmachno

References

- 1 2 Baring-Gould, S; Fisher, John (1908). The Lives of the British Saints (Volume 4). Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion/Charles J Clarke. p. 266.

- 1 2 "St Tudclud's Church, Penmachno". www.mochdrenews.co.uk/. HistoryPoints.org. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Bro Machno (Parish): Welsh Language Skills (detailed), 2011 (QS207WA)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ "Ty Mawr Wybrnant". National Trust. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- 1 2 Jenkins, Robert Thomas. "Jones , Owen Gethin". wbo.llgc.org.uk. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Owen Gethin Jones". www.festipedia.org.uk. Festipedia. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ "Pont Gethin, Betws-y-Coed". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "St Mary's Church, Betws-y-Coed". www.historypoints.org. HistoryPoints.org. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- 1 2 Gethin Jones, Owen (9 April 2012). Gweithiau Gethin: Sef Casgliad O Holl Weithiau Barddonol A Llenyddol... Nabu Press. ISBN 1279821396.

- ↑ Tyler, Ric (18 August 2011). Dugoed, Penmachno, Betws-y-Coed, Conwy - Architectural Record - Final Report. The North-West Wales Dendrochronology Project. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Morris, Olwen; Jones, Gill; Richardson, Frances (2013). Dugoed, Penmachno, Betws-y-Coed, Conwy. Coflein. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Gill. "Coed y Ffynnon, Penmachno, Conwy". www.coflein.gov.uk. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Simpkin, W; Marshall, R (1820). The Cambro-Briton Volume 1. London: Simpkin and Marshall. p. 212.

- ↑ "Huw Machno - Biography". wbo.llgc.org.uk. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Richie Thomas". www.sainwales.com. Sain Recordiau. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Plaque unveiled on Penmachno tenor Richie Thomas' home". www.dailypost.co.uk. North Wales Daily Post. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Hydref, Elen. "Dadorchuddio plac coffa Richie Thomas, Penmachno". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Penmachno Caernarvonshire". www.visionofbritain.org.uk. Vision of Britain. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "PMCH1/1". www.ucl.ac.uk. University College London. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Bannister, Paul. "The Real King Arthur". www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/endeavour-press/. Endeavour Press. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Hassell, Alan. "Carausius King of the Britain". www.thunting.com. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ "St Tudclud's Church, Penmachno, Conwy (Bwrdeistref Sirol), North Wales". www.thejournalofantiquities.com. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Geoffrey of Monmouth; Roberts, Peter (1811). The Chronicle of the Kings of Britain (translation from Welsh). London: E Williams. p. 93.

- ↑ "PMCH1/3". www.ucl.ac.uk. University College London. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Prysor, Dewi. "Bryn y Castell: History and Legend". www.darnbachohanes.com. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ Davies, John (2007). A History of Wales (Revised ed.). UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140284751.

- ↑ "PMCH1/2". www.ucl.ac.uk. University College London. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "PMCH2/1". www.ucl.ac.uk. University College London. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ See 'Britain, the Byzantine Empire, and the concept of an Anglo-Saxon 'Heptarchy': Harun ibn Yahya's ninth-century Arabic description of Britain', by Caitlin Green, on http://www.caitlingreen.org/2016/04/heptarchy-harun-ibn-yahya.html. See footnote 12 of that article for instances of other historians who agree with Dr Green's suggestion.

- ↑ "A history of Saint Tudclud's Church". parish.churchinwales.org.uk. The Parish of Betws-y-Coed, Capel Curig, Penmachno & Dolwyddelan. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Penmachno, Conwy County". www.walesdirectory.co.uk. Wales Directory. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Wales Census 1851 - Penmachno Factory". home.ancestry.co.uk/. Ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "PENMACHNO WOOLLEN MILL; FACTORY ISAF, PENMACHNO". www.coflein.gov.uk. Coflein. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Penmachno Roman Bridge". www.coflein.gov.uk. Coflein. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Penmachno". mbwales.com. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Castle, Samantha (5 June 2008). "Penmachno residents reject mountain bike trail car park and visitor centre". North Wales Weekly News. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Penmachno. |

- Penmachno.net : Tourism site for the village

- www.geograph.co.uk : Photos of Penmachno and surrounding area

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales : Photos of the interior of St Tudclud's Church, the 12th century font and the early Christian stone slabs

- www.megalith.co.uk : Photos of the 13th century grave stone and the early Christian stone slabs

- www.peoplescollectionwales.co.uk : Photo of Penmachno Woolen Mill Shop in 1964

- www.peoplescollectionwales.co.uk : Photo of interior of Penmachno Woolen Mill