Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States term for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. It was the US portion of what are called Peaceful Nuclear Explosions (PNE).

Successful demonstrations of non-combat uses for nuclear explosives include rock blasting, stimulation of tight gas, chemical element manufacture (test shot Anacostia resulted in Curium-250m being discovered), unlocking some of the mysteries of the so-called "r-Process" of stellar nucleosynthesis and probing the composition of the Earth's deep crust, creating reflection seismology Vibroseis data which has helped geologists and follow on mining company prospecting.[1][2][3]

The un-characteristically large and atmospherically vented Sedan (nuclear test) of the project, also led geologists to determine that Barringer crater was formed as a result of a meteor impact and not from a volcanic eruption, as had earlier been assumed. This became the first crater on Earth, definitely proven to be from an impact event.[4]

Negative impacts from Project Plowshare’s 27 nuclear projects generated significant public opposition, which eventually led to the program's termination in 1977.[5] These consequences included Tritiated water (projected to increase by CER Geonuclear Corporation to a level of 2% of the then-maximum level for drinking water)[6] and the deposition of fallout from radioactive material being injected into the atmosphere before underground testing was mandated by treaty.

A similar Soviet program was carried out under the name Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy.

Rationale

By exploiting the peaceful uses of the "friendly atom" — in medical applications, earth removal, and later in nuclear power plants — the nuclear industry and government sought to allay public fears about nuclear technology and promote the acceptance of nuclear weapons. At the peak of the Atomic Age, the United States Federal government initiated Project Plowshare, involving "peaceful nuclear explosions". The United States Atomic Energy Commission chairman at the time, Lewis Strauss, announced that the Plowshares project was intended to "highlight the peaceful applications of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests".[7][8]

Proposals

Proposed uses for nuclear explosives under Project Plowshare included widening the Panama Canal, constructing a new sea-level waterway through Nicaragua nicknamed the Pan-Atomic Canal, cutting paths through mountainous areas for highways, and connecting inland river systems. Other proposals involved blasting underground caverns for water, natural gas, and petroleum storage. Serious consideration was also given to using these explosives for various mining operations. One proposal suggested using nuclear blasts to connect underground aquifers in Arizona. Another plan involved surface blasting on the western slope of California's Sacramento Valley for a water transport project.[5]

Project Carryall,[9] proposed in 1963 by the Atomic Energy Commission, the California Division of Highways (now Caltrans), and the Santa Fe Railway, would have used 22 nuclear explosions to excavate a massive roadcut through the Bristol Mountains in the Mojave Desert, to accommodate construction of Interstate 40 and a new rail line.[5] At the end of the program, a major objective was to develop nuclear explosives, and blast techniques, for stimulating the flow of natural gas in "tight" underground reservoir formations. In the 1960s, a proposal was suggested for a modified in situ shale oil extraction process which involved creation of a rubble chimney (a zone in the oil shale formation created by breaking the rock into fragments) using a nuclear explosive.[10] However, this approach was abandoned for a number of technical reasons.

Plowshare testing

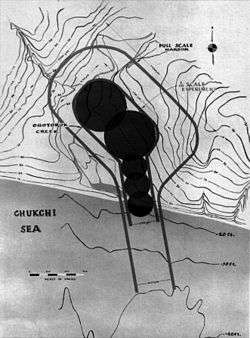

One of the first plowshare nuclear blast cratering proposals that came close to being carried out was Project Chariot, which would have used several hydrogen bombs to create an artificial harbor at Cape Thompson, Alaska. It was never carried out due to concerns for the native populations and the fact that there was little potential use for the harbor to justify its risk and expense.[11]

A number of proof-of-concept cratering blasts were conducted; including the Buggy shot of 5 1 kt devices for a channel/trench in Area 21 and the largest being 104 kiloton (435 terajoule) on July 6, 1962 at the north end of Yucca Flats, within the Atomic Energy Commission's Nevada Test Site (NTS) in southern Nevada. The shot, "Sedan", displaced more than 12 million short tons (11 teragrams) of soil and resulted in a radioactive cloud that rose to an altitude of 12,000 ft (3.7 km). The radioactive dust plume headed northeast and then east towards the Mississippi River.

The first PNE blast was Project Gnome, conducted on December 10, 1961 in a salt bed 24 mi (39 km) southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico. The explosion released 3.1 kilotons (13 TJ) of energy yield at a depth of 361 meters (1,184 ft) which resulted in the formation of a 170 ft (52 m) diameter, 80 ft (24 m) high cavity. The test had many objectives. The most public of these involved the generation of steam which could then be used to generate electricity. Another objective was the production of useful radioisotopes and their recovery. Another experiment involved neutron time-of-flight physics. A fourth experiment involved geophysical studies based upon the timed seismic source. Only the last objective was considered a complete success. The blast unintentionally vented radioactive steam while the press watched. The partly developed Project Coach detonation experiment that was to follow adjacent to the Gnome test was then canceled.

Over the next 11 years 26 more nuclear explosion tests were conducted under the U.S. PNE program. The radioactive blast debris from 839 U.S. underground nuclear test explosions remains buried in-place and has been judged impractical to remove by the DOE's Nevada Site Office. Funding quietly ended in 1977. Costs for the program have been estimated at more than (US) $770 million.[5]

Natural gas stimulation experiment

Three nuclear explosion experiments were intended to stimulate the flow of natural gas from "tight" formation gas fields. Industrial participants included El Paso Natural Gas Company for the Gasbuggy test; CER Geonuclear Corporation and Austral Oil Company for the Rulison test;[12] and CER Geonuclear Corporation for the Rio Blanco test.

The final PNE blast took place on 17 May 1973, under Fawn Creek, 76.4 km north of Grand Junction, Colorado. Three 30 kiloton detonations took place simultaneously at depths of 1,758, 1,875, and 2,015 meters. If it had been successful, plans called for the use of hundreds of specialized nuclear explosives in the western Rockies gas fields. The previous two tests had indicated that the produced natural gas would be too radioactive for safe use; the Rio Blanco test found that the three blast cavities had not connected as hoped, and the resulting gas still contained unacceptable levels of radionuclides.[13]

By 1974, approximately $82 million had been invested in the nuclear gas stimulation technology program. It was estimated that even after 25 years of production of all the natural gas deemed recoverable, only 15 to 40 percent of the investment would be recouped. Also, the concept that stove burners in California might soon emit trace amounts of blast radionuclides into family homes did not sit well with the general public. The contaminated gas was never channeled into commercial supply lines.

The situation remained so for the next three decades, but a resurgence in Colorado Western slope natural gas drilling has brought resource development closer and closer to the original underground detonations. By mid-2009, 84 drilling permits had been issued within a 3-mile radius, with 11 permits within one mile of the site.[14]

Nuclear tests

The U.S. conducted 27 PNE shots in conjunction with other, weapons-related, test series.[1] A report by the Federation of American Scientists includes yields slightly different than that presented below.[15]

| Test name | Date | Location | Type | Depth of Burial | Medium | Yield (kilotons) | Test series | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnome | 10 December 1961 | Carlsbad, New Mexico | Shaft | 1,185 ft (361 m) | Salt | 3 | Nougat | A multipurpose experiment designed to provide data concerning: (1) heat generated from a nuclear explosion; (2) isotopes production; (3) neutron physics; (4) seismic measurements in a salt medium; and (5) design data for developing nuclear devices specifically for peaceful uses. |

| Sedan | 6 July 1962 | Nevada Test Site | Crater | 635 ft (194 m) | Alluvium | 104 | Storax | A excavation experiment in alluvium to determine feasibility of using nuclear explosions for large excavation projects, such as harbors and canals; provide data on crater size, radiological safety, seismic effects, and air blast. |

| Anacostia | 27 November 1962 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 747 ft (227.7 m) | Tuff | 5.2 | Storax | A device-development experiment to produce heavy elements and provide radiochemical analysis data for the planned Coach Project. |

| Kaweah | 21 February 1963 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 745 ft (227.1 m) | Alluvium | 3 | Dominic I and II | A device-development experiment to produce heavy elements and provide technical data for the planned Coach Project. |

| Tornillo | 11 October 1963 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 489 ft (149 m) | Alluvium | 0.38 | Niblick | A device-development experiment to produce a clean nuclear explosive for excavation applications. |

| Klickitat | 20 February 1964 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 1,616 ft (492.6 m) | Tuff | 70 | Niblick | A device-development experiment to produce an improved nuclear explosive for excavation applications. |

| Ace | 11 June 1964 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 862 ft (262.7 m) | Alluvium | 3 | Niblick | A device-development experiment to produce an improved nuclear explosive for excavation applications. |

| Dub | 30 June 1964 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 848 ft (258.5 m) | Alluvium | 11.7 | Niblick | A device-development experiment to study emplacement techniques. |

| Par | 9 October 1964 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 1,325 ft (403.9 m) | Alluvium | 38 | Whetstone | A device-development experiment designed to increase the neutron flux needed for the creation of heavy elements. |

| Handcar | 5 November 1964 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 1,332 ft (406 m) | Dolomite (carbonate rock) | 12 | Whetstone | An emplacement experiment to study the effects of nuclear explosions in carbonate rock. |

| Sulky | 5 November 1964 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 90 ft (27.4 m) | Basalt | 0.9 | Whetstone | An excavation experiment to explore cratering mechanics in hard, dry rock and study dispersion patterns of airborne radionuclides released under these conditions. |

| Palanquin | 14 April 1965 | Nevada Test Site | Crater | 280 ft (85.3 m) | Rhyolite | 4.3 | Whetstone | An excavation experiment in hard, dry rock to study dispersion patterns of airborne radionuclides released under these conditions. |

| Templar | 24 March 1966 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 495 ft (150.9 m) | Tuff | 0.37 | Flintlock | To develop an improved nuclear explosive for excavation applications. |

| Vulcan | 25 June 1966 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 1,057 ft (322.2 m) | Alluvium | 25 | Flintlock | A heavy element device-development test to evaluate neutron flux performance. |

| Saxon | 11 July 1966 | Nevada Test Site | 1.2 kt | 502 ft (153 m) | Tuff | 1.2 | Latchkey | A device-development experiment to improve nuclear explosives for excavation applications. |

| Simms | 6 November 1966 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 650 ft (198.1 m) | Alluvium | 2.3 | Latchkey | A device-development experiment to evaluate clean nuclear explosives for excavation applications. |

| Switch | 22 June 1967 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 990 ft (301.8 m) | Tuff | 3.1 | Latchkey | A device-development experiment to evaluate clean nuclear explosives for excavation applications. |

| Marvel | 21 September 1967 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 572 ft (174.3 m) | Alluvium | 2.2 | Crosstie | An emplacement experiment to investigate underground phenomenology related to emplacement techniques. |

| Gasbuggy | 10 December 1967 | Farmington, New Mexico | Shaft | 4,240 ft (1,292 m) | Sandstone, gas bearing formation | 29 | Crosstie | A gas stimulation experiment to investigate the feasibility of using nuclear explosives to stimulate a low-permeability gas field; first Plowshare joint government-industry nuclear experiment to evaluate an industrial application. |

| Cabriolet | 26 January 1968 | Nevada Test Site | Crater | 170 ft (51.8 m) | Rhyolite | 2.3 | Crosstie | An excavation experiment to explore cratering mechanics in hard, dry rock and study dispersion patterns of airborne radionuclides released under these conditions. |

| Buggy | 12 March 1968 | Nevada Test Site | Crater | 135 ft (41.1 m) | Basalt | 5 at 1.1 each | Crosstie | A five-detonation excavation experiment to study the effects and phenomenology of nuclear row-charge excavation detonations. |

| Stoddard | 17 September 1968 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 1,535 ft (467.9 m) | Tuff | 31 | Bowline | A device-development experiment to develop clean nuclear explosives for excavation applications. |

| Schooner | 8 December 1968 | Nevada Test Site | Crater | 365 ft (111.3 m) | Tuff | 30 | Bowline | An excavation experiment to study the effects and phenomenology of cratering detonations in hard rock. |

| Rulison | 10 September 1969 | Grand Valley, Colorado | Shaft | 8,425 ft (2,567.9 m) | Sandstone | 43 | Mandrel | A gas stimulation experiment to investigate the feasibility of using nuclear explosives to stimulate a low-permeability gas field; provide engineering data on the use of nuclear explosions for gas stimulation; on changes in gas production and recovery rates; and on techniques to reduce the radioactive contamination to the gas. |

| Flask -Green, -Yellow, -Red | 26 May 1970 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | Green, 1736 ft (529.2 m); Yellow, 1,099 ft (335 m); Red, 499 ft (152.1 m) | Green, Tuff; Yellow and Red, Alluvium | Green, 105; Yellow, 0.9; Red, 0.4 tons | Mandrel | A three-detonation device development experiment to develop improved nuclear explosives for excavation applications. |

| Miniata | 8 July 1971 | Nevada Test Site | Shaft | 1,735 ft (528.8 m) | Tuff | 83 | Grommet | To develop a clean nuclear explosive for excavation applications. |

| Rio Blanco -1, -2, -3 | 17 May 1973 | Rifle, Colorado | Shaft | 5,840 ft (1,780 m); 6,230 ft (1,898.9 m); 6,690 ft (2,039.1 m) | Sandstone, gas-bearing formation | 3 at 33 each | Toggle | A gas stimulation experiment to investigate the feasibility of using nuclear explosives to stimulate a low-permeability gas field; develop technology for recovering natural gas from reservoirs with very low permeability. |

Non-nuclear tests

In addition to the nuclear tests, Plowshare executed a number of non-nuclear test projects in an attempt to learn more about how the nuclear explosives could best be used. Several of these projects led to practical utility as well as to furthering knowledge about large explosives. These projects included:[1]

| Test name | Date | Location | Type | Depth of Burial | Medium | Yield | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Gnome | February 10–16, 1959 | Southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico | seismic experiment (High explosive) | 1,200 ft (365.8 m), each | Bedded salt | 3.65 tons | Three seismic experiments to measure ground shock for the planned GNOME nuclear test. |

| Toboggan | November- December 1959 & April–June 1960 | Nevada Test Site | ditching experiment (High explosive, TNT) | 3 to 20 ft (1 to 6.1 m) | Playa (combination of silt and clay) | Series of 122 detonations of both linear and point HE charges | Study ditching characteristics of both-end detonated and multidetonated HE explosives in preparation for nuclear row charge experiments. |

| Hobo | February- April 1960 | Nevada Test Site | seismic experiment (High explosive, TNT) | Unknown | Tuff | Three explosions, varying from 500 to 1,000 lb. charges each | To study rock fracturing and related phenomena produced by contained explosions. |

| Stagecoach | March 1960 | Nevada Test Site | excavation experiment (High explosive, TNT) | Shot 1 – 80 ft (24.4 m); Shot 2 - 17.1 ft (5.2 m); Shot 3 - 34.2 ft (10.4 m) | Alluvium | Three 40,000 lb. charges | Examine blast, seismic effects and throw out characteristics in preparation for nuclear cratering experiments. |

| Plowboy | March–July 1960 | Winnfield, Louisiana | experiment | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Mining operation to examine high explosive- induced fracturing of salt. |

| Buckboard | July–September 1960 | Nevada Test Site | excavation experiment (High explosive, TNT) | 5 to 59.85 ft (1.5 to 18.24 m) | Basalt | Three 40,000 lb. charges and ten 1,000 lb. charges | Establish depth of burst curves for underground explosives in a hard rock medium. |

| Pinot | August 2, 1960 | Rifle, Colorado | tracer experiment (High explosive, nitromethane) | 610 ft (185.9 m) | Oil shale | Unknown | To determine how gases in a confined underground explosion migrate. |

| Scooter | October 1960 | Nevada Test Site | excavation experiment (High explosive, TNT) | 125 ft (38.1 m) | Alluvium | 500 ton charges | To study crater dimension, throw out material distribution, ground motion, dust cloud growth, and long-range air blast. |

| Rowboat | June 1961 | Nevada Test Site | row-charge experiment (High explosive, TNT) | Varied | Alluvium | 8 detonations of series of four 278 lb. charges | To study the effects of depth of burial and charge separation on crater dimensions. |

| Yo-Yo | Summer 1961 | At LRL, near Tracy, California | simulated excavation experiment (High explosive) | Varied | Oil-sand mixture | 100 gm charges | To develop estimates for the quantities of radiation released to the atmosphere by a cratering detonation. |

| Pre-Buggy I | November 1962- February 1963 | Nevada Test Site | row-charge experiment (High explosive, nitromethane) | 15 to 21.4 ft (4.57 to 6.52 m) for single-charge detonations; all row-charge detonations at 19.8 ft (6.04 m) | Alluvium | Six single-charge detonations, four multiple-charge | U.S. Army Engineer Cratering Group Study of row- charge phenomenology and effects in preparation for nuclear row-charge tests. |

| Pre-Buggy II | June–August 1963 | Nevada Test Site | row-charge experiment (High explosive, nitromethane) | 18.5 to 23 ft (5.64 to 7.0 m) | Alluvium | Five rows of five 1,000 lb. charges | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study of row-charge phenomenology and effects in preparation for a nuclear row- charge experiment. |

| Pre-Schooner I | February 1964 | Nevada Test Site | cratering experiment (High explosive, nitromethane) | 42 to 66 ft (18.3 to 20.1 m) | Basalt | Four 40,000 lb. spherical charges | U.S. Army Engineer Nuclear Cratering Group study of basic cratering phenomenology in preparation for nuclear cratering experiments. |

| Dugout | June 24, 1964 | Nevada Test Site | row charge experiment (High explosive, nitromethane) | 59 ft (18.0 m) | Basalt | simultaneous detonation of a row of five 20 ton charges placed 45 feet (13.7 m) apart (1 crater radius) | Study fundamental processes involved in row charge excavating dense, hard rock. |

| Pre-Schooner II | September 30, 1965 | Owyhee County, southwestern Idaho | cratering experiment (high explosive, nitromethane) | 71 ft (21.6 m) | Rhyolite | 85 ton charge | Obtain data for proposed Schooner nuclear cratering test, particularly cavity growth, seismic effects, and air blast. |

| Pre-Gondola I, II, III | October 1966 - October 1969 | Near Fort Peck Reservoir, Valley County, Montana | excavation experiments (High explosive, nitromethane) | Varied | Saturated Bearclaw shale | Pre-Gondola I, four 20-ton charges; Pre-Gondola II, row of five charges totaling 140 tons; Pre-Gondola III, Phase I, three rows of seven one-ton charges; Phase II, one row of seven 30- ton charges; Phase III, one row of five charges varying from five to 35 tons and totaling 70 tons | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project to provide seismic calibration test data and cratering characteristics for excavation projects. |

| Tugboat | November 1969- December 1970 | Kawaihae Bay, Hawaii | excavation experiment (High explosive, TNT) | 4–8 ft (1.2-2.4 m) | Water | Unknown | To study excavation of a small boat harbor in a weak coral medium. |

| Trinidad | July–December 1970 | Trinidad, Colorado (six miles west) | excavation experiment (High explosive) | Unknown | Sandstone/shale | Unknown | Four series of row-charge detonations to study excavation designs. |

| Old Reliable | August 1971- March 1972 | Galiuro Mountains, 44 miles northeast Tucson, Arizona | fracturing experiment (High explosive, ammonium nitrate) | Unknown | Unknown | 2,002 tons | To promote fracturing and in situ leaching of copper ore. |

Proposed nuclear projects

A number of projects were proposed and some planning accomplished, but were not followed through on. A list of these is given here:[1]

| Name | Date | Location | Type | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxcart | 1959 | Nevada Test Site | Nuclear explosive | Investigate excavation efficiency as a function of yield and depth in planning for Project Chariot. |

| Oilsands | 1959 | Athabasca, Canada | Nuclear explosive | Study the feasibility of oil recovery using a nuclear explosive detonation in the Athabascan tar sands. |

| Oil Shale | 1959 | Not determined | Nuclear explosive | Study a nuclear detonation to shatter an oil shale formation to extract oil. |

| Ditchdigger | 1961 | Not determined | Nuclear explosive | A deeply buried clean nuclear explosive detonation excavation experiment |

| Coach | 1963 | Carlsbad, NM (GNOME site) | Nuclear explosive | Produce neutron-rich isotopes of known trans- plutonium elements. |

| Phaeton | 1963 | Not determined | Nuclear explosive | Scaling experiment. |

| Carryall | Nov-63 | Bristol Mountains Mojave Desert, CA | Nuclear explosive | Row-charge excavation experiment to cut through the Bristol Mountains for realignment of the Santa Fe railroad and a new highway I-40. |

| Dogsled | 1964 | Colorado Plateau CO or AZ | Nuclear explosive | Study cratering characteristics in dry sandstone; study ground shock and air blast intensities. |

| Tennessee/ Tombigee Waterway | 1964 | Northeast Mississippi | Nuclear explosive | Excavation of three miles of a divide cut through low hills; connect Tennessee and Tombigee rivers; dig 250-mile long canal. |

| Interoceanic Sea-Level Canal Study | 1965-70 | Pan-American Isthmus (Central America) | Nuclear explosive | Commission appointed in 1965 to conduct feasibility studies of several sea-level routes for an Atlantic- Pacific interoceanic canal. Two routes were in Panama and one in northwestern Colombia. The 1970 final report recommended, in part, that no current U.S. canal policy should be made on the basis that nuclear excavation technology will be available for canal construction. AEC deferred in making any decision. |

| Flivver | Mar-66 | Nevada Test Site | Nuclear explosive | A low-yield cratering detonation to study basic cratering phenomenology. |

| Dragon Trail | Dec-66 | Rio Blanco County, CO | Nuclear explosive | Natural gas stimulation experiment; different geological characteristics than either GASBUGGY or RULISON; geological study completed. |

| Ketch | Aug-67 | Renovo, PA (12 miles SW) | Nuclear explosive | Create a large chimney of broken rock with void space to store natural gas under high pressure. |

| Bronco | Oct-67 | Rio Blanco County, CO | Nuclear explosive | Break oil shale deposits for in situ retorting; exploratory core holes drilled. |

| Sloop | 10/67-68 | Safford, AZ (11 miles NE) | Nuclear explosive | Fracturing copper ore; extract copper by in situ leaching methods; feasibility study completed. |

| Thunderbird | 1967 | Buffalo, WY (35 miles E) | Nuclear explosive | Coal gasification; fracture rock-containing coal and in situ combustion of the coal would produce low-Btu gas and other products. |

| Galley | 1967-68 | Not determined | Nuclear explosive | A high-yield row charge in hard rock under terrain of varying elevations. |

| Aquarius | 1968-70 | Clear Creek or San Simon, AZ | Nuclear explosive | Water resource management; dam construction, subsurface storage, purification; aquifer modification. |

| Wagon Wheel | 01/68-74 | Pinedale, WY (19 miles S) | Nuclear explosive | Natural gas stimulation; study stimulation at various depths; an exploratory hole and two hydrological wells were drilled. |

| Wasp | 07/69-74 | Pinedale, WY (24 miles NW) | Nuclear explosive | Natural gas stimulation; meteorological observations taken. |

| Utah | 1969 | near Ouray, UT | Nuclear explosive | Oil shale maturation; exploratory hole drilled. |

| Sturtevant | 1969 | Nevada Test Site | Nuclear explosive | Cratering experiment to extend excavation information on yields and rock types relevant to the trans-Isthmian canal. |

| Australian Harbor Project | 1969 | Cape Keraudren (NW coast of Australia) | Nuclear explosive | First discussed with U.S. officials in 1962, the U.S. formally agreed to participate in a joint feasibility study with the Australian government in early 1969 for using nuclear explosives to construct a harbor. The project was stopped in March 1969 when it was determined that there was an insufficient economic basis to proceed. |

| Yawl | 1969-70 | Nevada Test Site | Nuclear explosive | Cratering experiment to extend excavation information on yields and rock types relevant to the trans-Isthmian canal. |

| Geothermal Power Plant | 1971 | Not determined | Nuclear explosive | Geothermal resource experiment; fracturing would allow fluids circulated in fracture zones to be converted to steam to generate electricity.[1] |

Impacts, opposition and economics

Operation Plowshare "started with great expectations and high hopes". Planners believed that the projects could be completed safely, but there was less confidence that they could be completed more economically than conventional methods. Moreover, there was insufficient public and Congressional support for the projects. Projects Chariot and Coach were two examples where technical problems and environmental concerns prompted further feasibility studies which took several years, and each project was eventually canceled.[1]

Citizen groups voiced concerns and opposition to some of the Plowshare tests. There were concerns that the blast effects from the Schooner explosion could dry up active wells or trigger an earthquake. There was opposition to both Rulison and Rio Blanco tests because of possible radioactive gas flaring operations and other environmental hazards.[1] In a 1973 article, Time used the term "Project Dubious" to describe Operation Plowshare.[13]

There were negative impacts from a select few of Project Plowshare’s 27 nuclear explosions, primarily those conducted in the projects infancy and those that were very high in explosive yield.

On Project Gnome and the Sedan test:[5]

Project Gnome vented radioactive steam over the very press gallery that was called to confirm its safety. The next blast, a 104-kiloton detonation at Yucca Flat, Nevada, displaced 12 million tons of soil and resulted in a radioactive dust cloud that rose 12,000 feet and plumed toward the Mississippi River. Other consequences – blighted land, relocated communities, tritium-contaminated water, radioactivity, and fallout from debris being hurled high into the atmosphere – were ignored and downplayed until the program was terminated in 1977, due in large part to public opposition.[5]

Project Plowshare shows how something intended to improve national security can unwittingly do the opposite if it fails to fully consider the social, political, and environmental consequences. It also “underscores that public resentment and opposition can stop projects in their tracks”.[5]

While the above social scientist, Benjamin Sovacool contends that the main problem with oil and gas stimulation, which many considered as the most promising economic use of nuclear detonations, was the problem that the produced oil and gas was radioactive, which caused consumers to reject it and this was ultimately the programs downfall.[5] In contrast, Oil and gas are sometimes considerably naturally radioactive to begin with and the industry is set up to deal with oil and gas that contain radioactive contaminants, moreover in contrast to earlier stimulation efforts,[20] contamination from many later tests was not a show-stopping issue, historian Dr. Michael Payne notes that it was primarily changing public opinion due to the societal preception-shift, to one fearing all nuclear detonations, caused by events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, that resulted in protests,[21] court cases and general hostility that ended the oil and gas stimulation efforts. Furthermore, as the years went by without further development and the closing/curtailment in output of nuclear weapons factories, this evaporated the existing economies of scale advantage of operation Plowshare that had earlier been present in the United States in the 50s-60s, it was increasingly found in the following decades that most US fields could instead be stimulated by non-nuclear techniques which were found to be likely cheaper.[22][23]

As a point of comparison, the most successful and profitable nuclear stimulation effort that did not result in customer product contamination issues was the 1976 Project Neva on the Sredne-Botuobinsk gas field in the Soviet Union, made possible by multiple cleaner stimulation explosives, favorable rock strata and the possible creation of an underground contaminant storage cavity.[24][25] The Soviet Union retains the record for the cleanest/lowest fission-fraction nuclear devices so far demonstrated.

The public records for devices that produced the highest proportion of their yield via fusion-only reactions, and therefore created orders of magnitude smaller amounts of long lived fission products as a result, are the USSRs Peaceful nuclear explosions of the 1970s, with the 3 detonations that excavated part of Pechora–Kama Canal, being cited as 98% fusion each in the Taiga test's three 15 kiloton explosive yield devices, that is, a total fission fraction of 0.3 kilotons in a 15 kt device.[26] In comparison, the next three high fusion yielding devices were all much too high in total explosive yield for oil and gas stimulation, the 50 megaton Tsar Bomba achieved a yield 97% derived from fusion,[27] While in the US, the 9.3 megaton Hardtack Poplar test is reported as 95.2%,[28] and the 4.5 megaton Redwing Navajo test as 95% derived from fusion.[29]

Books

- IAEA review of the 1968 book: The constructive uses of nuclear explosions by Edward Teller.

- “The Containment of Underground Nuclear Explosions”, Project Director Gregory E van der Vink, U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA-ISC-414, (Oct 1989).

See also

- Plowshares Movement

- Atoms for Peace

- Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy - the equivalent Soviet program(s) that achieved "practical application" status.

- Atomic age

- Project Oilsand, a 1958 proposal to exploit the Athabasca Oil Sands in Canada via the underground detonation of nuclear bombs.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Executive Summary: Plowshare Program" (PDF). US Department of Energy, Office of Science and Technical Information. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ http://wayback.archive.org/web/20060210141005/http://www.ociw.edu/ociw/symposia/series/symposium4/ms/becker.ps.gz

- ↑ Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series

- ↑ Impact Processes: Meteor Crater, Arizona. Nuclear explosions often excavated craters identical to those attributed to meteorite impacts. TheKE released in these blasts was known to the weapons designers, so here was a relationship between energy and crater size. This information was eventually made public, and planetary geoscientists made use of this relationship to estimate the KE needed to excavate impact craters of various sizes and ages, on Earth and other planet

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sovacool, Benjamin K (2011), "Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy", World Scientific: 171–2

- ↑ Jacobsen, Sally (May 1972). "Turning up the Gas: AEC Prepares Another Nuclear Gas Stimulation Shot". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 28 (5): 37. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ↑ Hewlett, Richard G.; Holl, Jack M. (1989). Atoms for Peace and War, 1953-1961: Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 529.

highlight the peaceful applications of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests

- ↑ "semiannual report to Congress in January 1958". Other mentions of Strauss making statements in Feb 1958 or hearings being held are on p 447, and 474 it seems. p.474's quotation: Senate Subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations, Hearings on Control and Reduction of Armaments, Feb. 28-April 17, 1958, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1958) pp.1336-64.

- ↑ "Preliminary Design Studies In A Nuclear Excavation — Project Carryall" (50). Highway Research Board. 1964: 32–39. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ Lombard, DB; Carpenter, HC (1967). "Recovering Oil by Retorting a Nuclear Chimney in Oil Shale". Journal of Petroleum Technology. Society of Petroleum Engineers (19): 727–34.

- ↑ O'Neill, Dan (2007) [1995], The Firecracker Boys: H-Bombs, Inupiat Eskimos, and the Roots of the Environmental Movement, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00348-6

- ↑ "Austral Oil, Co., Inc.". Harvard Business School. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- 1 2 "Environment: Project Dubious". Time magazine. Apr 9, 1973. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ Jaffe, Mark (2009-07-02). "Colorado drilling rigs closing in on '60s nuke site". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ↑ "RESTRICTED DATA DECLASSIFICATION DECISIONS 1946 TO THE PRESENT, RDD-7, January 1, 2001.". Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ talkingsticktv (7 November 2007). "Declassified U.S. Nuclear Test Film #35" – via YouTube.

- ↑ Guinness World Records. "Largest crater from an underground nuclear explosion". Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ↑ "The Soviet Nuclear Weapons Program". Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ↑ Russia Today documentary that visits the lake at around the 1 minute mark on YouTube

- ↑ ""Gasbuggy" tests Nuclear Fracking - American Oil & Gas Historical Society". 4 December 2015.

- ↑ "Innovation Alberta: Article Details". 24 August 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-08-24.

- ↑ Plowshare Program Executive Summary, pg 4-5

- ↑ "elmada.com/wagon: Nuclear Stimulation Projects". 6 July 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-07-06.

- ↑ "The Soviet Program for Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Explosions".

- ↑ Milo D. Nordyke, 2000. peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs) in the Soviet Union over the period 1965 to 1988.

- ↑ The Soviet Program for Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Explosions by Milo D. Nordyke. Science & Global Security, 1998, Volume 7, pp. 1-117

- ↑ 4.5 Thermonuclear Weapon Designs and Later Subsections. Nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

- ↑ Operation Hardtack I. Nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

- ↑ Operation Redwing. Nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Plowshare. |

- "Plowshare (1961)- US Atomic Energy Commission" on YouTube

- Bolt, Bruce A (1976), Nuclear Explosions and Earthquakes: The Parted Veil, San Francisco, CA, US: WH Freeman & Co, ISBN 0-7167-0276-2.

- Hansen, Chuck (1988), US Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History, Arlington, TX: Aerofax, ISBN 0-517-56740-7.

- ———, The Swords of Armageddon: US Nuclear Weapons Development Since 1945 (CD-ROM), US cold war, retrieved 2016-08-17.

- Kirsch, Scott (2005), Proving Grounds: Project Plowshare and the Unrealized Dream of Nuclear Earthmoving, New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press.

- Miller, Richard L (1999), Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing, Woodlands, TX: Two Sixty Press, ISBN 1-881043-05-3.

- Schwartz, Stephen I, ed. (1998), Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, ISBN 0-8157-7773-6, retrieved 2016-08-17.

- "United States Nuclear Tests, July 1945 through September 1992" (PDF). US: Department of Energy Nevada Operations Office. December 2000. DOE/NV-209-REV15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-15.

- Plowshare Program (PDF), OSTI, retrieved 2016-08-17.

- "Background", Radioactive I-131 from Fallout, National Cancer Institute.

- "Executive Summary", Estimated Exposures and Thyroid Doses Received by the American People from Iodine-131 in Fallout Following Nevada Atmospheric Nuclear Bomb Tests (report), National Cancer Institute,

Figure 1 – Per capita thyroid doses resulting from all exposure routes from all test

. - Focused Evaluation of Selected Remedial Alternatives for the Underground Test Area (PDF), Nevada, US: Environmental Restoration Division, Operations Office, Department of Energy, April 1997, DOE/NV-465.

- "Plowshare", NV (PDF), US: DOE,

Declassification of the yields of 11 nuclear tests conducted as part of the plowshare... program

. - "Plowshare Program", Atomic traveler (PDF) (chronology) milestones, including proposed tests and projects conducted.

- The short film Plowshare (Part I) (ca. 1961) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film Plowshare (Part II) (ca. 1961) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film New Mexico, 1961/11/30 (1961) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film Radiation Safety in Nuclear Energy Explorations (Part I) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film Radiation Safety in Nuclear Energy Explorations (Part II) is available for free download at the Internet Archive