Official Communications of the Chinese Empire

The Chinese Empire, which lasted from the 221 BCE until 1911, required predictable forms and means of communication. Documents flowed down from the Emperor to officials, from officials to the Emperor, from one part of the bureaucracy to others, and from the Emperor or his officials to the people. These documents, especially memorials to the throne, were preserved in collections which became more voluminous with each passing dynasty and make the Chinese historical record extraordinarily rich.

This article briefly describes the major forms and types of communication going up to and down from the emperor.

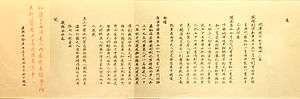

Edicts, orders, and proclamations to the people

Under Chinese law, the emperor's edicts had the force of law. By the time the Han dynasty (206 BCE- 2nd Century CE) established the basic patterns of bureaucracy, edicts or commands could be issued either by the emperor or in the emperor's name by the proper official or unit of the government. Important edicts were carved on stone tablets for public inspection.[1] One modern scholar counted more than 175 different terms for top down commands, orders, edicts, and such.

Edicts formed a recognized category of prose writing. The Qing dynasty scholar Yao Nai ranked "Edicts and orders" (Zhao-ling) as one of the thirteen categories of prose writing, citing prototypes which went back to the Zhou dynasty and the Book of History. Han dynasty edicts, sometimes actually written by high officials in the name of the emperor, were known for their literary quality. In later dynasties, both emperors and officials who wrote in the emperor's name published collections of edicts.[2]

The history of China features a range of famous edicts and instructions. Here are examples in chronological order:

- The First Emperor of the Qin dynasty, for instance, issued an edict in 213 BCE ordering the burning of books and burying of scholars.

- Upon coming to the throne of the Ming dynasty in 1368, the Hongwu Emperor, issued a series of Great Warnings which informed his people and his bureaucracy of their failings and his instructions to correct them.[3]

- He also issued The Instructions of the Ancestor, in effect an edict to his descendents.

He instructed his people:

Treat your parents with piety; respect your elders and superiors; live at peace in your villages; instruct your children and grandchildren; make your living peacefully; commit no wrong.[4] - The Kangxi Emperor's Sacred Edict issued in 1670 and expanded and reprinted by his son, the Yongzheng Emperor, in Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol versions in 1724, was to be posted in every village and read periodically to the assembled population.[5]

- The Qianlong Emperor's "Edict to the King of England" (1793) instructing him that England had nothing of value to offer.[6]

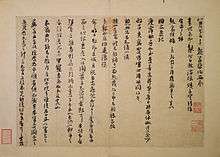

Memorials

A Memorial, most commonly zouyi, was the most important form of document sent by an official to the Emperor. In the early dynasties, the terms and formats of the memorial were fluid, but by the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), codes and statutes specified what terminology could be used by what level of official in what particular type of document dealing with what particular type of problem. Criminal codes specified punishments for mistranscriptions or using a character that was forbidden because it was used in one of the emperor's names. The Emperor might reply at length, perhaps dictating a rescript in response. More often he made a notation in the margin in vermilion ink (which only the emperor could use) stating his wishes. Or he might simply write "forward to the proper ministry," "noted," or use his brush to make a circle, the equivalent of a checkmark, to indicate that he had read the document.[7]

By the height of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) in the 18th century, memorials from bureaucrats at the central, provincial, and county level supplied the emperors (and modern historians) with personnel evaluations, crop reports, prices in local markets, weather predictions, intelligence on social affairs, and any other matter of possible interest.[8]

Memorials were transported by government couriers and then copied and summarized by the Grand Secretariat, which itself had been perfected in the preceding Ming dynasty. They would be copied by clerks and entered into official registers.[9]

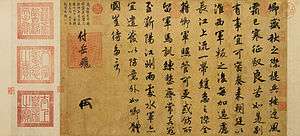

This bureaucracy saved the emperor from being swamped with tedious detail but might also shield him from information which he needed to know. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1672-1720), the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1720-1736), and the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1793) therefore developed a supplementary system of "Palace Memorials" (zouzhe) which they instructed local officials to send directly, without passing through bureaucratic filters. One type, the "Folding Memorial," was written on a page small enough for the Emperor to hold in his hand and read without being observed.[10] The Yongzheng Emperor, who preferred the written system over audiences, increased the use of these palace memorials by more than ten times over his father. He found he could get quick responses to emergency requests instead of waiting for the formal report, or give frank instructions: Of one official he said, “he is good-hearted, hard-working old hand. I think he’s very good. But he’s a bit coarse... just like Zhao Xiangkui, except that Zhao is intelligent.” Likewise a provincial governor could frankly report that a subordinate was “scatter brained.” The emperor could then instruct the official to also submit a routine memorial. Most important, bypassing the regular bureaucracy made it easier for the emperor to have his own way without being restricted by the regulations of the administrative code.[11]

The system of memorials and rescripts, even more than personal audiences, was the emperor's way to shape and cement relations with his officials. Memorials could be quite specific and even personal, since the emperor knew many of his officials quite well. The Kangxi Emperor, for instance, wrote one of his generals:

- "I am fine. It is cool now outside the passes. There has been enough rain so the food now is very good... You're an old man -- are grandfather and grandmother both well?"

But sometimes impatience broke through: "Stop the incessant sending of these greetings!" or "I hear tell you've been drinking. If after receiving my edict you are not able to refrain, and so turn your back on my generosity, I will no longer value you or your services." [12] The historian Jonathan Spence translated and joined together memorials of the Kangxi Emperor to form an autobiographical "self-portrait" which gives an feel for the emperor's place in the flow of government.[13]

References

- Ch. 20 "Official Communications," in Endymion Wilkinson. Chinese History: A New Manual. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series. New Edition; Second, Revised printing March 2013; ISBN 9780674067158, pp. 280–285.

- Beatrice S. Bartlett. Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723-1820. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991). ISBN 0520065913.

- Silas H. L. Wu. Communication and Imperial Control in China: Evolution of the Palace Memorial System, 1693-1735. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; Harvard East Asian Series, 1970). ISBN 0674148010.

Notes

- ↑ Endymion Wilkinson. Chinese History: A Manual. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series Rev. and enl., 2000. ISBN 0674002474), pp. 532-533.

- ↑ William H. Nienhauser. The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), p. 96-97.

- ↑ Anita M. Andrew and John A. Rapp. Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors: Comparing Chairman Mao and Ming Taizu. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000; ISBN 0847695794), esp. pp. 60-68.

- ↑ Wilkinson (2013): 281.

- ↑ Spence, The Search for Modern China (New York: Norton; 3rd,

- ↑ Ssu-Yü Têng, John King Fairbank, ed., China's Response to the West: A Documentary Survey, 1839-1923. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1954), p. 19

- ↑ Wilkinson. Chinese History: A Manual. p. 534-35.

- ↑ Jonathan D. Spence. The Search for Modern China. (New York: Norton, 2nd 1999. pp. 70-71, 87.

- ↑ Silas H. L. Wu. Communication and Imperial Control in China: Evolution of the Palace Memorial System, 1693-1735. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; Harvard East Asian Series, 1970). ISBN 0674148010.

- ↑ Mark C. Elliott. The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0804736065 pp. 164, 161-162.

- ↑ Beatrice S. Bartlett. Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723-1820. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991; ISBN 0520065913): 48-53.

- ↑ Elliott, The Manchu Way, p. 161

- ↑ Jonathan D. Spence. Emperor of China: Self Portrait of K'ang Hsi (New York: Vintage Books, 1975). ISBN 0394714113.