Neural mechanisms of mindfulness meditation

| Part of a series on |

| Mindfulness |

|---|

|

|

Other |

| Category:Mindfulness |

Mindfulness has been defined in modern psychological terms as "paying attention to relevant aspects of experience in a nonjudgmental manner",[1] and maintaining attention on present moment experience with an attitude of openness and acceptance.[2] Meditation is a platform used to achieve mindfulness. Both practices, mindfulness and meditation, have been "directly inspired from the Buddhist tradition"[3] and have been widely promoted by Jon Kabat-Zinn. Mindfulness meditation has been shown to have a positive impact on several psychiatric problems such as depression and therefore has formed the basis of mindfulness programs[4] such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction. The applications of mindfulness meditation are well established, however the mechanisms that underlie this practice are yet to be fully understood.

.jpg)

Mechanism of action of mindfulness meditation

Four components of mindfulness meditation have been proposed to describe much of the mechanism of action by which mindfulness meditation may work: attention regulation, body awareness, emotion regulation, and change in perspective on the self.[4] All of the components described above are connected to each other. For example, when a person is triggered by an external stimulus, the executive attention system attempts to maintain a mindful state. There is also a heightened body awareness such as a rapid heartbeat which triggers an emotional response. The response is then regulated so that it does not become habitual, but constantly changes from moment to moment experience. This eventually leads to a change in the perspective of the self.

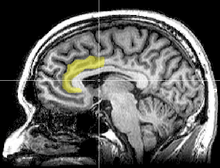

Attention regulation

Attention regulation is the task of focusing attention on an object, acknowledging any distractions, and then returning your focus back to the object. Some evidence for mechanisms responsible for attention regulation during mindfulness meditation are shown below.

- Mindfulness meditators showed greater activation of rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC).[5] This suggests that meditators have a stronger processing of conflict/distraction and are more engaged in emotional regulation. However, as the meditators become more efficient at focused attention, regulation becomes unnecessary and consequentially decreases activation of ACC in the long term.[6]

- The cortical thickness in the dorsal ACC was also found to be greater in the gray matter of experienced meditators.[7]

- There is an increased frontal midline theta rhythm, which is related to attention demanding tasks and is believed to be indicative of ACC activation.[8]

The ACC detects conflicting information coming from distractions. When a person is presented with a conflicting stimulus, the brain initially processes the stimulus incorrectly. This is known as error-related negativity (ERN). Before the ERN reaches a threshold, the correct conflict is detected by the frontocentral N2. After the correction, the rostral ACC is activated and allows for executive attention to the correct stimulus.[9] Therefore, mindfulness meditation could potentially be a method for treating attention related disorders such as ADHD and bipolar disorder.

Body awareness

Body awareness refers to focusing on an object/task within the body such as breathing. From a qualitative interview with ten mindfulness meditators, some of the following responses were observed: "When I'm walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving" and "I notice how foods and drinks affect my thoughts, bodily sensations, and emotions”.[10] The two possible mechanisms by which a mindfulness meditator can experience body awareness are discussed below.

- Meditators showed a greater cortical thickness [11] and greater gray matter concentration in the right anterior insula.[12]

- On the contrary, subjects who had undergone 8 weeks of mindfulness training showed no significant change in gray matter concentration of the insula, but rather an increase gray matter concentration of the temporo-parietal junction.[13]

The insula is responsible for awareness to stimuli and the thickness of its gray matter correlates to the accuracy and detection of the stimuli by the nervous system.[14][15] Qualitative evidence suggests that mindfulness meditation impacts body awareness, however this component is not well characterized.[4]

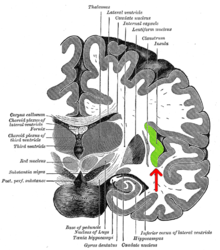

Emotion regulation

_Abnormal_Brain_Structures.png)

Emotions can be regulated cognitively or behaviorally. Cognitive regulation (in terms of mindfulness meditation) means having control over giving attention to a particular stimuli or by changing the response to that stimuli. The cognitive change is achieved through reappraisal (interpreting the stimulus in a more positive manner) and extinction (reversing the response to the stimulus). Behavioral regulation refers to inhibiting the expression of certain behaviors in response to a stimulus. Research suggests two main mechanisms for how mindfulness meditation influences the emotional response to a stimulus.

- Mindfulness meditation regulates emotions via increased activation of the dorso-medial PFC and rostral ACC.[5]

- Increased activation of the ventrolateral PFC can regulate emotion by decreasing the activity of the amygdala.[16][17][18] This was also predicted by a study that observed the effect of a person's mood/attitude during mindfulness on brain activation.[19]

Lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC) is important for selective attention while ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) is involved in inhibiting a response. As noted before, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) has been noted for maintaining attention to a stimulus. The amygdala is responsible for generating emotions. Mindfulness meditation is believed to be able to regulate negative thoughts and decrease emotional reactivity through these regions of the brain. Emotion regulation deficits have been noted in disorders such as borderline personality disorder [20] and depression.[21] These deficits have been associated with reduced prefrontal activation and increased amygdala activity, which mindfulness meditation might be able to attenuate.

Applications of mindfulness meditation

Pain relief

Pain is known to activate the following regions of the brain: the anterior cingulate cortex, anterior/posterior insula, primary/secondary somatosensory cortices, and the thalamus.[22] Mindfulness meditation may provide several methods by which a person can consciously regulate pain.[22]

- Brown and Jones found that mindfulness meditation decreased pain anticipation in the right parietal cortex and mid-cingulate cortex. Mindfulness meditation also increased the activity of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and ventromedial-prefrontal cortex (vm-PFC). Since the vm-PFC is involved in inhibiting emotional responses to stimuli, anticipation to pain was concluded to be reduced by cognitive and emotional control.[23]

- Another study by Grant revealed that meditators showed greater activation of insula, thalamus, and mid-cingulate cortex while a lower activation of the regions responsible for emotion control (medial-PFC, OFC, and amygdala). Meditators were believed to be in a mental state that allowed them to pay close attention to the sensory input from the stimuli and simultaneously inhibit any appraisal or emotional reactivity.[7]

Brown and Jones found that meditators showed no difference in pain sensitivity but rather the anticipation in pain. However, Grant's research showed that meditators experienced lower sensitivity to pain. These conflicting studies illustrate that the exact mechanism may vary with the expertise level or meditation technique.[22]

Immune Response

It has been shown that greater left-sided anterior activation might correlate with better immune function measured by NK activity.[24] There is also some evidence showing that a stressful life has a negative impact on these antibody titers.[25] Antibody titers are a way to measure the antibody level in the body as a response to foreign substances. Since several meditation programs are aimed at reducing stress, the impact of mindfulness meditation on an immune response was considered.

- When comparing the immune function of patients who had participated in an 8-week mindfulness meditation program to those who did not, it was found that meditators had greater antibody titers in response to an influenza vaccine. Since a larger role of left-sided anterior activation was observed, it may have been responsible for greater antibody titers.[26]

References

- ↑ "MIndfulness in medicine". JAMA. 300 (11): 1350–1352. 2008-09-17. doi:10.1001/jama.300.11.1350. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ↑ Bishop, Scott R.; Lau, Mark; Shapiro, Shauna; Carlson, Linda; Anderson, Nicole D.; Carmody, James; Segal, Zindel V.; Abbey, Susan; Speca, Michael (2004-09-01). "Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 11 (3): 230–241. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph077. ISSN 1468-2850.

- ↑ Desbordes, Gaëlle; Gard, Tim; Hoge, Elizabeth A.; Hölzel, Britta K.; Kerr, Catherine; Lazar, Sara W.; Olendzki, Andrew; Vago, David R. (2014-01-21). "Moving Beyond Mindfulness: Defining Equanimity as an Outcome Measure in Meditation and Contemplative Research". Mindfulness. 6 (2): 356–372. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0269-8. ISSN 1868-8527. PMC 4350240

. PMID 25750687.

. PMID 25750687. - 1 2 3 Holzel B. K.; Lazar S. W.; Gard T.; Schuman-Olivier Z.; Vago D. R.; Ott U. (2011). "How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6 (6): 537–559. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671. PMID 26168376.

- 1 2 Hölzel B.K.; Ott U.; Hempel H.; Hackl A.; Wolf K.; Stark R.; Vaitl D. (2007). "Differential engagement of anterior cingulate cortex and adjacent medial frontal cortex in adept meditators and nonmeditators". Neuroscience Letters. 421: 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.074.

- ↑ Brefczynski-Lewis J.A.; Lutz A.; Schaefer H.S.; Levinson D.B.; Davidson R.J. (2007). "Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104: 11483–11488. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606552104.

- 1 2 Grant J.A.; Courtemanche J.; Duerden E.G.; Duncan G.H.; Rainville P. (2010). "Cortical thickness and pain sensitivity in Zen meditators". Emotion. 10: 43–53. doi:10.1037/a0018334.

- ↑ Asada H.; Fukuda Y.; Tsunoda S.; Yamaguchi M.; Tonoike M. (1999). "Frontal midline theta rhythms reflect alternative activation of prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex in humans". Neuroscience Letters. 274: 29–32. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00679-5.

- ↑ van Veen V.; Carter C.S. (2002). "The anterior cingulate as a conflict monitor: FMRI and ERP studies". Physiology & Behavior. 77: 477–482. doi:10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00930-7.

- ↑ Hölzel, B.K., Ott, U., Hempel, H., & Stark, R. (2006, May). Wie wirkt Achtsamkeit? Eine Interviewstudie mit erfahrenen Meditierenden(How does mindfulness work? An interview study with experienced meditators). Paper presented at the 24th Symposium of the Section for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy of the German Society for Psychology, Würzburg, Germany.

- ↑ Lazar S.W.; Kerr C.E.; Wasserman R.H.; Gray J.R.; Greve D.N.; Treadway M.T.; Fischl B. (2005). "Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness". NeuroReport. 16: 1893–1897. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19. PMC 1361002

. PMID 16272874.

. PMID 16272874. - ↑ Hölzel B.K.; Ott U.; Gard T.; Hempel H.; Weygandt M.; Morgen K.; Vaitl D. (2008). "Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 3: 55–61. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm038.

- ↑ Hölzel B.K.; Carmody J.; Vangel M.; Congleton C.; Yerramsetti S.M.; Gard T.; Lazar S.W. (2011). "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Research. 191: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMC 3004979

. PMID 21071182.

. PMID 21071182. - ↑ Craig A.D. (2003). "Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 13: 500–505.

- ↑ Critchley H.D.; Wiens S.; Rotshtein P.; Ohman A.; Dolan R.J. (2004). "Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness". Nature Neuroscience. 7: 189–195. doi:10.1038/nn1176. PMID 14730305.

- ↑ Harenski C.L.; Hamann S. (2006). "Neural correlates of regulating negative emotions related to moral violations". NeuroImage. 30: 313–324. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.034.

- ↑ Beauregard M.; Levesque J.; Bourgouin P. (2001). "Neural correlates of conscious self-regulation of emotion". Journal of Neuroscience. 21: RC165.

- ↑ Schaefer S.M.; Jackson D.C.; Davidson R.J.; Aguirre G.K.; Kimberg D.Y.; Thompson-Schill S.L. (2002). "Modulation of amygdalar activity by the conscious regulation of negative emotion". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 14: 913–921. doi:10.1162/089892902760191135.

- ↑ Creswell J.D.; Way B.M.; Eisenberger N.I.; Lieberman M.D. (2007). "Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling". Psychosomatic Medicine. 69: 560–565. doi:10.1097/psy.0b013e3180f6171f.

- ↑ Silbersweig D.; Clarkin J.F.; Goldstein M.; Kernberg O.F.; Tuescher O.; Levy K.N.; Rauch S.L. (2007). "Failure of frontolimbic inhibitory function in the context of negative emotion in borderline personality disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry. 164: 1832–1841. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06010126.

- ↑ Abercrombie H.C.; Schaefer S.M.; Larson C.L.; Oakes T.R.; Lindgren K.A.; Holden J.E.; Davidson R.J. (1998). "Metabolic rate in the right amygdala predicts negative affect in depressed patients". NeuroReport. 9: 3301–3307. doi:10.1097/00001756-199810050-00028.

- 1 2 3 Zeidan F.; Grant J. A.; Brown C. A.; McHaffie J. G.; Coghill R. C. (2012). "Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: Evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain". Neuroscience Letters. 520 (2): 165–173. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082.

- ↑ Brown C.A.; Jones A.K. (2010). "Meditation experience predicts less negative appraisal of pain: electrophysiological evidence for the involvement of anticipatory neural responses". Pain. 150 (3): 428–438. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.017.

- ↑ Kang DH, Davidson RJ, Coe CL, Wheeler RW, Tomarken AJ, Ershler WB (1991). "Frontal brain asymmetry and immune function". Behav Neurosci. 105: 860–9.

- ↑ Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, Sheridan J (1996). "Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 93: 3043–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.7.3043.

- ↑ Davidson R. J.; Kabat-Zinn J.; Schumacher J.; Rosenkranz M.; Muller D.; Santorelli S. F.; Sheridan J. F. (2003). "Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation". Psychosomatic Medicine. 65 (4): 564–570. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3.