Morris Lapidus

| Morris Lapidus | |

|---|---|

| Born |

November 25, 1902 Odessa, Ukraine |

| Died |

January 18, 2001 (aged 98) Miami Beach, Florida, United States |

| Nationality | Ukrainian Jewish |

| Alma mater | Columbia University (B.A., Architecture, 1927)[1] |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings |

Fontainebleau Miami Beach Eden Roc |

| Projects | Lincoln Road Mall |

Morris Lapidus (November 25, 1902 – January 18, 2001) was an architect, primarily known for his Neo-baroque "Miami Modern" hotels constructed in the 1950s and 60s, which have since come to define that era's resort-hotel style — synonymous with Miami and Miami Beach.

A Russian immigrant based in New York, Lapidus designed over 1,000 buildings during a career spanning more than 50 years, much of it spent as an outsider to the American architectural establishment.

Early life and career

Born in Odessa in the Russian Empire (now Ukraine), his Orthodox Jewish family fled Russian pogroms to New York when he was an infant. As a young man, Lapidus toyed with theatrical set design and studied architecture at Columbia University, graduating in 1927.[1] Lapidus worked for the prominent Beaux Arts firm of Warren and Wetmore. He then worked independently for 20 years as a retail architect before being approached to design vacation hotels on Miami Beach.

After a career in retail interior design, his first large commission was the Miami Beach Sans Souci Hotel (opened 1949, after 1996 called the RIU Florida Beach Hotel), followed closely by the Nautilus, the Di Lido, the Biltmore Terrace, and the Algiers, all along Collins Avenue, and amounting to the single-handed redesign of an entire district. The hotels were an immediate popular success.

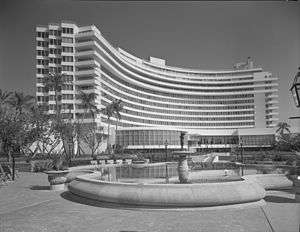

Then in 1952 he landed the job of the largest luxury hotel in Miami Beach, the property he is most associated with, the Fontainebleau Hotel, which was a 1,200 room hotel built by Ben Novack on the former Firestone estate, and perhaps the most famous hotel in the world.[2] It was followed the next year by the equally successful Eden Roc Hotel and the Americana (later the Sheraton Bal Harbour) in 1956. The Sheraton was demolished by implosion shortly after dawn on Sunday, November 18, 2007.

In 1955, Lapidus designed the Ponce de Leon Shopping Center near the plaza in St. Augustine, Florida. The anchor store, Woolworth's, was the scene of the first sit-in by black demonstrators from Florida Memorial College in March, 1960, and in 1963 by four young teenagers, who came to be known as the "St. Augustine Four." The Woolworth's door-handles and a Freedom Trail marker memorialize the events.

The Lapidus style is idiosyncratic and immediately recognizable in photographs, derived as it was from the attention-getting techniques of commercial store design: sweeping curves, theatrically backlit floating ceilings, 'beanpoles', and the ameboid shapes that he called 'woggles', 'cheeseholes', and painter's palette shapes. His many smaller projects give Miami Beach's Collins Avenue its style, anticipating post-modernism. Beyond visual style, there is some degree of functionalism at work. His curving walls caught the prevailing ocean breezes in the era before central air-conditioning, and the sequence of his interior spaces was the result of careful attention to user experience: Lapidis heard complaints of endless featureless hotel corridors and when possible would curve his hallways to avoid the effect.

The Fontainbleau was built on the site of the Harvey Firestone estate and defined the new Gold Coast of Miami Beach. The hotel provided locations for the 1960 Jerry Lewis film The Bellboy, a success for both Lewis and Lapidus, and the James Bond thriller Goldfinger (1964). Its most famous feature is the 'Staircase to Nowhere' (formally called the "floating staircase"), which merely led to a mezzanine-level coat check and ladies' powder-room, but offered the opportunity to make a glittering descent into the hotel lobby.

- "My whole success is I've always been designing for people, first because I wanted to sell them merchandise. Then when I got into hotels, I had to rethink, what am I selling now? You're selling a good time."

During the period before his death, Lapidus' style came back into focus. It began with his designing upbeat restaurants on Miami Beach and the Lincoln Road Mall. Lapidus was also honored by the Society of Architectural Historians at a convention held at the Eden Roc hotel in 1998. In 2000, the Smithsonian's Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum honored Lapidus as an American Original for his lifetime of work. Lapidus was quoted saying, "I never thought I would live to see the day when, suddenly, magazines are writing about me, newspapers are writing about me."

Personal

His son, architect Alan Lapidus, who worked with his father for 18 years, said, "His theory was if you create the stage setting and it's grand, everyone who enters will play their part."

In 2001, Morris Lapidus died from heart failure at the age of 98 at his Miami Beach apartment. Morris Lapidus' wife of 63 years, Beatrice, had died in 1992.

Critical reception

Lapidus designed 1,200 buildings, including 250 hotels worldwide. The American architectural establishment regarded Lapidus as an outsider, tried to ignore his work, then characterized it as gaudy kitsch.[3] Ada Louise Huxtable, writing in the New York Times, said of the Americana, "The effect on arrival was like being hit by an exploding gilded eggplant."[4] This abusive critical reception perhaps culminated in a 1963 American Institute of Architects (AIA) meeting held at the Americana, where a variety of well-known architects including Paul Rudolph, Robert Anshen and Wallace Harrison took Lapidus to task for what they described as vulgarity, cheapness, and incompetence.[5]

A 1970 Architectural League exhibit in New York began the serious appraisal of his work. Lapidus tried to ignore the critical panning, but it had an effect on his career and reputation. He burned 50 years' worth of his drawings when he retired in 1984 and remained personally bitter about some aspects of his career. He was rediscovered in the post-modernist era: the very title of his autobiography Too Much is Never Enough, 1996, is an allusion to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's dictum 'Less is more.' According to his German biographer Martina Duttmann, he has always been more highly regarded in Europe than in the U.S., where the comparable jet-set futurism is designated "Googie". Today, books published by the AIA such as Architect's Essentials of Starting a Design Firm 2003, refer positively to Morris Lapidus' works.

Projects

List adapted from Works in Lapidus autobiography.

- Martin's Department Store, Brooklyn, New York 1944

- Bond Clothing Stores flagship store, 372 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York, 1948

- Grossinger's Catskill Resort Hotel, multiple buildings from 1949[6] (abandoned)

- Ainsley Building / Foremost Building / One Flager, Miami, Florida, 1952

- Fontainebleau Hotel, Miami Beach, Florida, 1954

- Ponce de Leon Shopping Center, St. Augustine, Florida, 1955[7]

- Eden Roc Miami Beach Hotel, Miami Beach, Florida, 1955

- Aruba Hotel, now Radisson Aruba Resort, Aruba, 1955

- Americana of Bal Harbour Hotel, Miami Beach, Florida, 1956, demolished 2007

- Deauville Resort, Miami Beach, Florida, 1950s

- Concord Resort Hotel, Catskills, New York, Imperial Room night club and multiple other projects from the mid-1950s[8] (demolished)

- Golden Triangle Motor Hotel, Norfolk, Virginia 1959–60; interiors only[9]

- Lincoln Road, Miami Beach, Florida, 1960

- Sheraton Motor Inn, now Chinese Consulate, New York, New York, 1959

- The Summit Hotel, now Doubletree Metropolitan Hotel, New York, 1960

- Ponce de Leon Hotel, later Hilton San Jeronimo Hotel, now The Condado Plaza Hilton, San Juan, 1960

- Congregation Shaare Zion, Brooklyn, New York, 1960

- Richmond Motel, Richmond, Virginia, 1961

- The Americana of New York Hotel, now Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel, New York, New York, 1961

- The Americana of San Juan Hotel, now InterContinental San Juan, San Juan, 1961

- International Inn, now Washington Plaza Hotel, Washington, D.C., 1962

- Capitol Skyline Hotel, Washington, D.C., 1962

- Temple Menorah, Miami Beach, Florida, 1962 (since remodeled)

- 1800 G Street NW, Washington, D.C., 1962

- Crystal House Condominium, 5055 Collins Avenue, Miami Beach, FL, 1962

- El Conquistador Resort, Fajardo, Puerto Rico, 1965

- San Juan Intercontinental Hotel, now El San Juan Hotel, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1965

- Seacoast 5151, Miami Beach, Florida, 1966

- Temple Judea, 5500 Granada Boulevard, Coral Gables, Florida, 1966

- 1100 L Street NW, Washington, D.C., 1967

- Portman Square Hotel, London, England 1967

- Whitman (Co-op apartments) 75 Henry Street, Brooklyn, New York, 1968

- 1425 K Street NW, Washington, D.C., 1970 (since remodeled)

- TSS Mardi Gras, 1975

- TSS Carnivale, 1975

- Carnival Cruise Lines Terminal Building, Port of Miami, Miami, Florida, 1975

- Lausanne Apartments, Naples, Florida, 1978

- Grandview at Emerald Hills, Hollywood, Florida, 1981

References

- Notes

- 1 2 "Morris Lapidus / Mid 20th Century Historic District", City of Miami Beach Planning Department, July 14, 2009

- ↑ http://jmof.fiu.edu/

- ↑ "New York Architecture Images- Morris Lapidus". nyc-architecture.com. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ Ada Louise Huxtable, "Show Offers 'Joy' of Hotel Architecture," New York Times, October 15, 1970, 60.

- ↑ http://davidrifkind.org/fiu/library_files/esperdy%20lapidus.pdf

- ↑ Padluck, Ross (2013). Catskill Resorts:Lost Architecture of Paradise. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7643-4317-9.

- ↑ Lane, Marsha (3 June 2013). "Mural of large photos in downtown St. Augustine reflects city's history". St. Augustine Record. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Padluck, Ross (2013). Catskill Resorts:Lost Architecture of Paradise. Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7643-4317-9.

- ↑ "Radisson Hotel (Golden Triangle Hotel)". Society of Architectural Historians, SAH Archipedia.

As designed by Anthony F. Musolino, a long driveway, flanked by two curving ramps, leads to the motor entrance; there was once a circular fountain at its center. Glass curtain walls sheathe the thirteen-story V-shaped tower. Behind the tower, two motel-like wings stretch to the rear of the site with a pool at their center and parking spaces around their perimeter. In contrast to the relatively staid exterior, the hotel's interiors were the work of Morris Lapidus

- Bibliography

- Dunlop, Beth, "Iconic Lapidus, Reflections on an Architect's Journey from Scorned to Revered," The Miami Herald, 13 June 2010, Page 3M.

- Ringen, Jonathan, "Lapidus of Luxury", Metropolis magazine, 2007

External links

- Photos and highlights of Lapidus' career.

- Sketch of Lapidus' career.

- Frances Loeb Library: Bibliography.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morris Lapidus. |