Methemoglobin

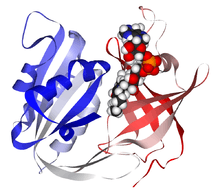

Methemoglobin (English: methaemoglobin) (pronounced "met-hemoglobin") is a form of the oxygen-carrying metalloprotein hemoglobin, in which the iron in the heme group is in the Fe3+ (ferric) state, not the Fe2+ (ferrous) of normal hemoglobin. Methemoglobin cannot bind oxygen, unlike oxyhemoglobin.[2] It is bluish chocolate-brown in color. In human blood a trace amount of methemoglobin is normally produced spontaneously, but when present in excess the blood becomes abnormally dark bluish brown. The NADH-dependent enzyme methemoglobin reductase (diaphorase I) is responsible for converting methemoglobin back to hemoglobin.

Normally one to two percent of a person's hemoglobin is methemoglobin; a higher percentage than this can be genetic or caused by exposure to various chemicals and depending on the level can cause health problems known as methemoglobinemia. A higher level of methemoglobin will tend to cause a pulse oximeter to read closer to 85% regardless of the true level of oxygen saturation.[3]

Common causes of elevated methemoglobin

- Reduced cellular defense mechanisms

- Children younger than 4 months exposed to various environmental agents

- Pregnant women are considered vulnerable to exposure of high levels of nitrates in drinking water[4]

- Cytochrome b5 reductase deficiency

- G6PD deficiency

- Hemoglobin M disease

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- Various pharmaceutical compounds

- Local anesthetic agents, especially prilocaine and benzocaine.[5]

- Amyl nitrite, chloroquine, dapsone, nitrates, nitrites, nitroglycerin, nitroprusside, phenacetin, phenazopyridine, primaquine, quinones and sulfonamides

- Environmental agents

- Aromatic amines (e.g. p-nitroaniline, patient case)

- Arsine

- Chlorobenzene

- Chromates

- Nitrates/nitrites

- Inherited disorders

- Some family members of the Fughate family in Kentucky, due to a recessive gene, had blue skin from an excess of methemoglobin.[6]

- In cats

- Ingestion of Paracetamol (i.e. acetaminophen, tylenol)

Therapeutic uses

Amyl nitrite is administered to treat cyanide poisoning. It works by converting hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which allows for the binding of cyanide and the formation of non-toxic cyanomethemoglobin.[7]

Methemoglobin saturation

Methemoglobin saturation is expressed as the percentage of hemoglobin in the methemoglobin state; That is MetHb as a proportion of Hb.

- 1-2% Normal

- Less than 10% metHb - No symptoms

- 10-20% metHb - Skin discoloration only (most notably on mucous membranes)

- 20-30% metHb - Anxiety, headache, dyspnea on exertion

- 30-50% metHb - Fatigue, confusion, dizziness, tachypnea, palpitations

- 50-70% metHb - Coma, seizures, arrhythmias, acidosis

- Greater than 70% metHb - Death

Blood stains

Increased levels of methemoglobin are found in blood stains. Upon exiting the body, bloodstains transit from bright red to dark brown, which is attributed to oxidation of oxy-hemoglobin (HbO2) to methemoglobin (met-Hb) and hemichrome (HC).[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Bando, S.; Takano, T.; Yubisui, T.; Shirabe, K.; Takeshita, M.; Nakagawa, A. (2004). "Structure of human erythrocyte NADH-cytochromeb5reductase". Acta Crystallographica Section D. 60 (11): 1929–1934. doi:10.1107/S0907444904020645. PMID 15502298.

- ↑ http://www.rtso.ca/methemoglobin-causes-effects/

- ↑ Denshaw-Burke, Mary (2006-11-07). "Methemoglobinema". Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ Manassaram, D. M.; Backer, L. C.; Messing, R.; Fleming, L. E.; Luke, B.; Monteilh, C. P. (2010). "Nitrates in drinking water and methemoglobin levels in pregnancy: A longitudinal study". Environmental Health. 9: 60. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-9-60. PMC 2967503

. PMID 20946657.

. PMID 20946657. - ↑ http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm250024.htm

- ↑ http://abcnews.go.com/Health/blue-skinned-people-kentucky-reveal-todays-genetic-lesson/story?id=15759819#.T2oS0HqV2So

- ↑ Vale, J. A. (2001). "Cyanide Antidotes: from Amyl Nitrite to Hydroxocobalamin - Which Antidote is Best?". Toxicology. 168 (1): 37–38.

- ↑ Bremmer et al PloS One 2011 http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0021845

External links

- Methemoglobin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- MetHb Formation

- The Blue people of Troublesome Creek