Rumelia Eyalet

| Eyalet-i Rumeli | |||||

| Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire | |||||

| |||||

.png) | |||||

| Capital | Edirne, Sofia, Monastir 41°1′N 21°20′E / 41.017°N 21.333°ECoordinates: 41°1′N 21°20′E / 41.017°N 21.333°E | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | c. 1365 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1867 | |||

| Area | |||||

| • | 1844[1] | 124,630 km2 (48,120 sq mi) | |||

| Population | |||||

| • | 1844[1] | 2,700,000 | |||

| Density | 21.7 /km2 (56.1 /sq mi) | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

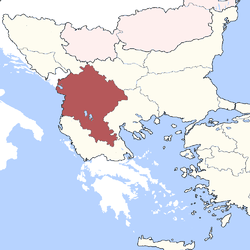

The Eyalet of Rumeli or Rumelia (Ottoman Turkish: ایالت روم ایلی; Eyālet-i Rūm-ėli),[2] also known as the Beylerbeylik of Rumeli, was a first-level province (beylerbeylik or eyalet) of the Ottoman Empire encompassing most of the Balkans ("Rumelia"). For most of its history it was also the largest and most important province of the Empire.

The capital was in Adrianople (Edirne), Sofia, and finally Monastir (Bitola). Its reported area in the 19th century was 48,119 square miles (124,630 km2).[3]

History

The first beylerbey of Rumelia was Lala Shahin Pasha, who was awarded the title by Sultan Murad I as a reward for his capture of Adrianople (modern Edirne) in the 1360s, and given military authority over the Ottoman territories in Europe, which he governed effectively as the Sultan's deputy while the Sultan returned to Anatolia.[4][5][6]

From its foundation, the province of Rumelia—initially termed beylerbeylik or generically vilayet ("province"), only after 1591 was the term eyalet used[4]—encompassed the entirety of the Ottoman Empire's European possessions, including the trans-Danubian conquests like Akkerman, until the creation of further eyalets in the 16th century, beginning with the Archipelago (1533), Budin (1541) and Bosnia (1580).[5][6]

The first capital of Rumelia was probably Edirne (Adrianople), which was also, until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottomans' capital city. It was followed by Sofia for a while and again by Edirne until 1520, when Sofia became the definite seat of the beylerbey.[6] At the time, the beylerbey of Rumelia was the commander of the most important military force in the state in the form of the timariot sipahi cavalry, and his presence in the capital during this period made him a regular member of the Imperial Council (divan). For the same reason, powerful Grand Viziers like Mahmud Pasha Angelovic or Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha held the beylerbeylik in tandem with the grand vizierate.[5]

In the 18th century, Monastir emerged as an alternate residence of the governor, and in 1836, it officially became the capital of the eyalet. At about the same time, the Tanzimat reforms, aimed at modernizing the Empire, split off the new eyalets of Üsküb, Yanya and Selanik and reduced the Rumelia Eyalet to a few provinces around Monastir. The rump eyalet survived until 1867, when, as part of the transition to the more uniform vilayet system, it became part of the Salonica Vilayet.[5][7][8]

Governors

- Lala Shahin Pasha, the first beylerbey of Rumelia, the lala (tutor) of Murad I.[9]

- Timurtaş Bey (1385–?)

- Süleyman Çelebi, son of Bayezid I[10] (before 1411)

- Musa Çelebi, son of Bayezid I (after 1411)

- Mustafa Bey (1421)[11]

- Hadım Şehabeddin (1439–42)[12]

- Kasım Pasha (1443)[13]

- Ömer Bey (fl. 1453)[14]

- Turahan Bey (before 1456)

- Mahmud Pasha (before 1456)

- Ahmed (after 1456)

- Hadım Süleyman Pasha (c. 1475)[15]

- Davud Pasha (c. 1478)[16]

- Sinan Pasha (c. 1481)[17]

- Mesih Pasha (after 1481)[18]

- Hasan Pasha (fl. 1514)[19]

- Ahmed Pasha (fl. 1521)[20]

- Güzelce Kasım Pasha (c. 1527)[21]

- Ibrahim (fl. 1537)[22]

- Khusrow Pasha (June 1538–?)[23]

- Ali Pasha (fl. 1546)[24]

- Sokollu Mehmed Pasha (fl. 1551[25])

- Doğancı Mehmed Pasha[26]

- Osman Yeğen Pasha (1687)[27]

- Sari Ahmed Pasha (1714[28]–1715)[29]

- Topal Osman Pasha (1721–27, 1729–30, 1731)[30]

- Hadži Mustafa Pasha (summer of 1797[31]–)

- Ali Pasha (1799[32] and again in 1802[33])

- Veli Pasha (1804)[34]

- Hurshid Pasha (fl. 1808)[35]

Administrative divisions

1475

A list dated to 1475 lists seventeen subordinate sanjakbeys, who controlled sub-provinces or sanjaks, which also functioned as military commands:[5]

- Constantinople

- Gallipoli

- Edirne

- Nikebolu/Nigbolu

- Vidin

- Sofia

- Serbia (Laz-ili)

- Serbia (Despot-ili)

- Vardar (under the Evrenosoğullari)

- Üsküb

- Arnawut-ili (under Iskender Bey, i.e. Skanderbeg)

- Arnawut-ili (under the Arianiti family)

- Bosnia

- Bosnia (under Stephen)

- Arta, Zituni and Athens

- Morea

- Monastir

1520s

Another list, dating to the early reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566), lists the sanjakbeys of that period, in approximate order of importance.:[5]

- Bey of the Pasha-sanjak

- Bosnia

- Morea

- Semendire

- Vidin

- Hersek

- Silistre

- Ohri

- Avlonya

- Iskenderiyye

- Yanya

- Gelibolu

- Köstendil

- Nikebolu

- Sofia

- Inebahti

- Tirhala

- Alaca Hișar

- Vulcetrin

- Kefe

- Prizren

- Karli-eli

- Ağriboz

- Çirmen

- Vize

- Izvornik

- Florina

- Elbasan

- Sanjakbey of the Çingene ("Gypsies")

- Midilli

- Karadağ (Montenegro)

- Sanjakbey of the Müselleman-i Kirk Kilise ("Muslims of Kirk Kilise")

- Sanjakbey of the Voynuks

The Çingene, Müselleman-i Kirk Kilise and Voynuks were not territorial circumscriptions, but rather represented merely a sanjakbey appointed to control these scattered and often nomadic groups, and who acted as the commander of the military forces recruited among them.[5] The Pasha-sanjak in this period comprised a wide area in western Macedonia, including the towns of Üskub (Skopje), Pirlipe (Prilep), Manastir (Bitola) and Kesriye (Kastoria).[5]

A similar list compiled c. 1534 gives the same sanjaks, except for the absence of Sofia, Florina and Inebahti (among the provinces transferred to the new Archipelago Eyalet in 1533), and the addition of Selanik (Salonica).[5]

1644

Further sanjaks were removed with the progressive creation of new eyalets, and an official register c. 1644 records only fifteen sanjaks for the Rumelia Eyalet:[5]

1700/1730

The administrative division of the beylerbeylik of Rumelia between 1700-1730 was as follows:[36]

Early 19th century

Sanjaks in the early 19th century:[37]

- Manastir

- Selanik

- Tirhala

- Iskenderiyye

- Ohri

- Avlonya

- Köstendil

- Elbasan

- Prizren

- Dukagin

- Üsküb

- Delvina

- Vulcetrin

- Kavala

- Alaca Hișar

- Yanya

Mid-19th century

According to the state yearbook (salname) of the year 1847, the reduced Rumelia Eyalet, centred at Manastir, encompassed also the sanjaks of Iskenderiyye (Scutari), Ohri (Ohrid) and Kesrye (Kastoria).[5] In 1855, according to the French traveller A. Viquesnel, it comprised the sanjaks of Iskenderiyye, with 7 kazas or sub-provinces, Ohri with 8 kazas, Kesrye with 8 kazas and the pasha-sanjak of Manastir with 11 kazas.[38]

Territorial evolution

Wholly or partly annexed to the Eyalet

- Byzantine Empire

- Second Bulgarian Empire, gradually conquered by the Ottomans in the late 14th-early 15th century.

- Lordship of Prilep, annexed in 1395

- Serbian Despotate, conquered by the Ottomans in 1459

- Kingdom of Bosnia, annexed in 1463

- Despotate of Dobruja

- Gazaria (Genoese colonies), annexed in 1475

- Principality of Theodoro, annexed in 1475

Created from the Eyalet

- Eyalet of the Archipelago (in 1533)

- Kefe Eyalet (in 1568)

- Bosnia Eyalet (in 1580)

- Silistra Eyalet (in 1593)

- Ioannina Eyalet (in 1670)

- Principality of Serbia (in 1815)

- In 1836, Rumelia was partitioned between three new eyalets: Salonica, Edirne and the rump Rumelia Eyalet around Monastir.

References

- 1 2 The Encyclopædia Britannica, or, Dictionary of arts, sciences ..., Volume 19. 1859. p. 464.

- ↑ "Some Provinces of the Ottoman Empire". Geonames.de. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ The Popular encyclopedia: or, conversations lexicon, Volume 6, p. 698, at Google Books

- 1 2 İnalcık, Halil (1991). "Eyālet". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 721–724. ISBN 90-04-07026-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 İnalcik, Halil (1995). "Rūmeli". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 607–611, esp. 610–611. ISBN 90-04-09834-8.

- 1 2 3 Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). 13. Reichert. p. 50. ISBN 9783920153568.

- ↑ Ursinus, M. (1991). "Manāstir". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 371–372. ISBN 90-04-08112-7.

- ↑ Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). 13. Reichert. pp. 50, 52. ISBN 9783920153568.

- ↑ Smailagic, Nerkez (1990), Leksikon Islama, Sarajevo: Svjetlost, p. 514, ISBN 978-86-01-01813-6, OCLC 25241734,

Sjedište beglerbega Rumelije ...prvi namjesnik, Lala Šahin-paša,...

- ↑ Kenneth M. Setton; Harry W. Hazard; Norman P. Zacour (1 June 1990). A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on Europe. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 699–. ISBN 978-0-299-10744-4.

- ↑ Vera P. Mutafchieva (1988). Agrarian relations in the Ottoman Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries. East European Monographs. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-88033-148-7. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ↑ Jefferson 2012, p. 280.

- ↑ Babinger 1992, p. 25.

- ↑ Aytaç Özkan (21 December 2015). Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror Great Eagle. Işık Yayıncılık Ticaret. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-1-59784-397-3.

- ↑ Ágoston & Masters 2009, p. 25.

- ↑ Marin Barleti (2012). The Siege of Shkodra: Albania's Courageous Stand Against Ottoman Conquest, 1478. David Hosaflook. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-99956-87-77-9.

- ↑ John Freely (1 October 2009). The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II-Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire. The Overlook Press. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-1-59020-449-8.

- ↑ Heath W. Lowry (1 February 2012). Nature of the Early Ottoman State, The. SUNY Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-0-7914-8726-6.

- ↑ Fatih Akçe (22 December 2015). The Conqueror of the East Sultan Selim I. Işık Yayıncılık Ticaret. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-1-68206-504-4.

- ↑ Stephen Turnbull (6 June 2014). The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-1-4728-1026-7.

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu; Julia Bailey (2008). Frontiers of Islamic Art and Architecture: Essays in Celebration of Oleg Grabar's Eightieth Birthday ; the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture Thirtieth Anniversary Special Volume. BRILL. pp. 98–. ISBN 90-04-17327-7.

- ↑ Lucette Valensi; Arthur Denner (1 December 2008). The Birth of the Despot: Venice and the Sublime Porte. Cornell University Press. pp. 19–. ISBN 0-8014-7543-0.

- ↑ Sir H. A. R. Gibb (1954). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Archive. pp. 35–. GGKEY:1FSD5PNQ2DE.

- ↑ Stephen Ortega (22 April 2016). Negotiating Transcultural Relations in the Early Modern Mediterranean: Ottoman-Venetian Encounters. Taylor & Francis. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-1-317-08919-3.

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 574.

- ↑ Ágoston & Masters 2009, p. 153.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık; Donald Quataert (1997-04-28). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 419. ISBN 978-0-521-57455-6. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ Novak, Viktor, ed. (1971). Istoriski časopis, Volumes 18-19. Srpska akademija nauka. Istoriski institut. p. 312.

- ↑ Kenneth Meyer Setton (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. American Philosophical Society. pp. 430–. ISBN 978-0-87169-192-7.

- ↑ Mantran, R. (2000). "Ṭopal ʿOt̲h̲mān Pas̲h̲a, 1. Grand Vizier (1663-1733)". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 564–565. ISBN 90-04-11211-1.

- ↑ Ćorović 1997

- ↑ Charles Jelavich; Barbara Jelavich (1 November 1986). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804-1920. University of Washington Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-295-96413-3.

- ↑ Ágoston & Masters 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ Michalis N. Michael; Matthias Kappler; Eftihios Gavriel (2009). Archivum Ottomanicum. Mouton. p. 175. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Ali Yaycioglu (4 May 2016). Partners of the Empire: The Crisis of the Ottoman Order in the Age of Revolutions. Stanford University Press. pp. 220–. ISBN 978-0-8047-9612-5.

- ↑ Orhan Kılıç, XVII. Yüzyılın İlk Yarısında Osmanlı Devleti'nin Eyalet ve Sancak Teşkilatlanması, Osmanlı, Cilt 6: Teşkilât, Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, Ankara, 1999, ISBN 975-6782-09-9, p. 91. (Turkish)

- ↑ The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful ..., Volume 25, p. 393, at Google Books — by George Long, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

- ↑ Viquesnel, Auguste (1868). Voyage dans la Turquie d'Europe: description physique et géologique de la Thrace (in French). Tome Premier. Paris: Arthus Betrand. pp. 107, 114–115.

Bibliography

- Babinger, Franz (1992) [1978]. Hickman, William C., ed. Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Translated by Manheim, Ralph. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01078-6.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. "Početak ustanka u Srbiji". Istorija srpskog naroda. Ars Libri.

- Jefferson, John (2012). The Holy Wars of King Wladislas and Sultan Murad: The Ottoman-Christian Conflict from 1438-1444. BRILL. p. 84. ISBN 90-04-21904-8.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1984). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Vol. IV: The Sixteenth Century. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87169-162-0.

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York, NY: Facts On File. ISBN 9780816062591.