Lough Neagh

| Lough Neagh Loch nEathach (Irish) Loch Neagh (Ulster-Scots)[1] | |

|---|---|

NASA Landsat image | |

| Location | Northern Ireland, UK |

| Coordinates | 54°37′06″N 6°23′43″W / 54.61833°N 6.39528°WCoordinates: 54°37′06″N 6°23′43″W / 54.61833°N 6.39528°W |

| Primary inflows | Upper Bann, Six Mile Water, Glenavy River, Crumlin River, Blackwater, Moyola River, Ballinderry River, River Main[2] |

| Primary outflows | Bann River |

| Catchment area | 1,760 sq mi (4,550 km2) |

| Basin countries |

Northern Ireland (91%) Republic of Ireland (9%) |

| Max. length | 19 mi (30 km) |

| Max. width | 9.3 mi (15 km) |

| Surface area | 151 sq mi (392 km2) |

| Average depth | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Max. depth | 82 ft (25 m) |

| Water volume | 7.76×1011 imp gal (3.528 km3) |

| Islands | (see below) |

| Designated | 5 January 1976 |

Lough Neagh, (pronounced /ˌlɒx ˈneɪ/, lokh nay) is a freshwater lake in Northern Ireland. The largest lake by area in the British Isles, it supplies 40% of Northern Ireland's water.[3][4] Its name comes from Irish: Loch nEachach, meaning "Lake of Eachaidh", although today it is usually spelt Loch nEathach (Irish: [ɫ̪ɔx ˈn̠ʲahax]) in Irish.[5] The lough is owned by the Earl of Shaftesbury.

Geography

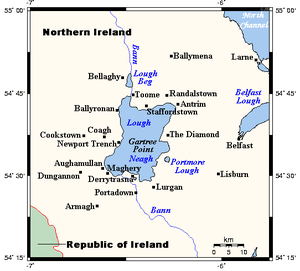

With an area of 151 square miles (392 km2), it is the largest lake on the island of Ireland, the 15th largest freshwater lake within the European Union[3][4] and is ranked 31st in the List of largest lakes of Europe. Located 20 miles (32 km) west of Belfast, it is about 20 miles (32 km) long and 9 miles (14 km) wide. It is very shallow around the margins and the average depth in the main body of the lake is about 30 feet (9 m), although at its deepest the lough is about 80 feet (24 m) deep.

Hydrology

Of the 1,760-square-mile (4,550 km2) catchment area, around 9% lies in the Republic of Ireland and 91% in Northern Ireland;[6] altogether 43% of the land area of Northern Ireland is drained into the lough,[7] which itself flows out northwards to the sea via the River Bann. As one of its sources is the Upper Bann, the Lough can itself be considered as part of the Bann. Lough Neagh is fed by many tributaries including the rivers Main (34 mi, 55 km), Six Mile Water (21 mi, 34 km), Upper Bann (40 mi, 64 km), Blackwater (57 mi, 92 km), Ballinderry (29 mi, 47 km) and Moyola (31 mi, 50 km)[8]

Islands and peninsulas

- Coney Island

- Coney Island Flat

- Croaghan Flat

- Derrywarragh Island

- Kinturk Flat

- Oxford Island (peninsula)

- Padian

- Ram's Island

- Phil Roe's Flat

- The Shallow Flat

- Traad (peninsula)

Towns and villages

Towns and villages near the Lough include Craigavon, Antrim, Crumlin, Randalstown, Toomebridge, Ballyronan, Ballinderry, Moortown, Ardboe, Maghery, Lurgan and Magherafelt.

Counties

Five of the six counties of Northern Ireland have shores on the Lough (only Fermanagh does not), and its area is split among them. The counties are listed clockwise:

- Antrim (eastern side and northern shore of the lake)

- Down (small part in the south-east)

- Armagh (south)

- Tyrone (west)

- Londonderry (northern part of west shore)

Local Government Districts

The area of the lake is split between four Local Government Districts of Northern Ireland, which are listed clockwise: [9]

- 3 Antrim and Newtownabbey, in the north-east

- 4 Lisburn and Castlereagh, in the east

- 6 Armagh, Banbridge and Craigavon, in the south

- 9 Mid Ulster, in the west

Uses

Although the Lough is used for a variety of recreational and commercial activities, it is exposed and tends to get extremely rough very quickly in windy conditions.

Water supply

The lough is used by Northern Ireland Water as a source of fresh water. The lough supplies 40% of the region's drinking water. There have long been plans to increase the amount of water drawn from the lough, through a new water treatment works at Hog Park Point, but these are yet to materialise.

The lough's ownership by the Earl of Shaftesbury has implications for planned changes to state-run domestic water services in Northern Ireland,[10] as the lough is also used as a sewage outfall, and this arrangement is only permissible through British Crown immunity. In 2012, it was reported that the Earl is considering transferring ownership of the Lough to the Northern Ireland Assembly.[11]

Navigation

Traditional working boats on Lough Neagh include wide-beamed 4.9-to-6.4-metre (16 to 21 ft) clinker-built, sprit-rigged working boats and smaller flat-bottomed "cots" and "flats". Barges, here called "lighters", were used until the 1940s to transport coal over the lough and adjacent canals. Until the 17th century, log boats (coití) were the main means of transport. Few traditional boats are left now, but a community-based group on the southern shore of the lough is rebuilding a series of working boats.[12]

In the 19th century, three canals were constructed, using the lough to link various ports and cities: the Lagan Navigation provided a link from the city of Belfast, the Newry Canal linked to the port of Newry, and the Ulster Canal led to the Lough Erne navigations, providing a navigable inland route via the River Shannon to Limerick, Dublin and Waterford. The Lower Bann was also navigable to Coleraine and the Antrim coast, and the short Coalisland Canal provided a route for coal transportation. Of these waterways, only the Lower Bann remains open today, although a restoration plan for the Ulster Canal is currently in progress.

Lough Neagh Rescue provides a search and rescue service 24 hours a day. It is a voluntary service funded by the district councils bordering the Lough. Its members are highly trained and are a declared facility for the Maritime and Coastguard Agency which co-ordinates rescues on Lough Neagh.

Bird watching

Lough Neagh attracts bird watchers from many nations due to the number and variety of birds which winter and summer in the boglands and shores around the lough.

Flora

The flora of the north-east of Northern Ireland includes the algae: Chara aspera, Chara globularis var. globularis, Chara globularis var. virgate, Chara vulgaris var. vulgaris, Chara vulgaris var. papillata, Tolypella nidifica var. glomerata.[13]Records of Angiospermae include: Ranunculus flammula var. pseudoreptans, Ranunculus auricomus, Ranunculatus sceleratus, Ranunculatus circinatus, Ranunculatus peltatus, Thalictrum flavum,Thalictrum minus subsp. minus, Nymphaea alba, Ceratophyllum demersum, Subularia aquatic, Erophila verna sub. verna, Cardamine pratensis, Cardamine impatiens, Cardamine flexuosa, Rorippa palustris, Rorippa amphibian, Reseda luteola, Viola odorata, Viola reichenbachiana, Viola tricolor ssp. Violoa tricolor ssp. curtissi, Hypericum androsaemum, Hypericum maculatum, Elatine hydropiper, Silene vulgaris, Silene dioica, Saponaria officinalis, Cerastium arvensis, Cerastium semidecandrum, Cerastium diffusum, Sagina nodosa, Spergularia rubra,Spergulaia rupicola, Chenopodium bonus-henricus, Chenopodium polyspermum [13]

Fishing

Eel fishing has been a major industry in Lough Neagh for centuries. These European eels make their way from the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, some 4,000 miles (6,000 km) along the Gulf Stream to the mouth of the River Bann, and then make their way into the lough. They remain there for some 10 to 15 years, maturing, before returning to the Sargasso to spawn. Today Lough Neagh eel fisheries export their eels to restaurants all over the world, and the Lough Neagh Eel has been granted Protected Geographical Status under European Union law.[14]

Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney produced a collection of poems A Lough Neagh Sequence celebrating the eel-fishermen's traditional techniques and the natural history of their catch.[15]

Mythology and folklore

In the Irish mythical tale Cath Maige Tuired ("the Battle of Moytura"), Lough Neagh is called one of the 12 chief loughs of Ireland.[16] The origin of the lake and its name is explained in an Irish tale that was written down in the Middle Ages, but is likely pre-Christian.[17][18] According to the tale, the lake is named after Echaid (modern spelling: Eochaidh or Eachaidh), who was the son of Mairid (Mairidh), a king of Munster. Echaid falls in love with his stepmother, a young woman named Ébliu (Ébhlinne). They try to elope, accompanied by many of their retainers, but someone kills their horses. In some versions, the horses are killed by Midir (Midhir), which may be another name for Ébliu's husband Mairid. Óengus (Aonghus) then appears and gives them an enormous horse that can carry all their belongings. Óengus warns that they must not let the horse rest or it will be their doom. However, after reaching Ulster the horse stops and urinates, and a spring rises from the spot. Echaid decides to build a house there and covers the spring with a capstone to stop it overflowing. One night, the capstone is not replaced and the spring overflows, drowning Echaid and most of his family, and creating Loch n-Echach (Loch nEachach: the lake of Eochaidh or Eachaidh).[17][18]

The character Eochaidh refers to The Daghdha, a god of the ancient Irish who was also known as Eochaidh Ollathair (meaning "horseman, father of all").[18] Ébhlinne, Midhir and Aonghus were also names of deities. Dáithí Ó hÓgáin writes that the idea of a supernatural being creating the landscape with its own body is an ancient one common to many pre-Christian cultures.[18] A Gaelic sept called the Uí Eachach (meaning "descendents of Eochaidh") dwelt in the area and it is likely that their name comes from the cult of the god Eochaidh.[17]

Another tale tells how the lake was formed when Ireland's legendary giant Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool) scooped up a chunk of earth and tossed it at a Scottish rival. It fell into the Irish Sea, forming the Isle of Man, while the crater left behind filled with water to form Lough Neagh.[19]

Gallery

Lough Neagh at Killywoolaghan, County Tyrone

Lough Neagh at Killywoolaghan, County Tyrone Lough Neagh near Ardmore Point

Lough Neagh near Ardmore Point Lough Neagh at Shane's Castle, County Antrim

Lough Neagh at Shane's Castle, County Antrim Lough Neagh at Gawley's Gate, County Antrim

Lough Neagh at Gawley's Gate, County Antrim Lough Neagh at Maghery, County Armagh

Lough Neagh at Maghery, County Armagh Lough Neagh at Ballyronan, County Londonderry

Lough Neagh at Ballyronan, County Londonderry

See also

References

- ↑ Naijural Heirship: Peat Mosses NI Environment and Heritage Service.

- ↑ Habitas.org

- 1 2 Official Tourism Ireland site

- 1 2 Britannica.com

- ↑ Deirdre Flanagan and Laurance Flanagan, Irish Placenames, (Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 1994)

- ↑ "Lough Neagh". UK Environmental Change Network. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Northern Ireland Rivers Agency

- ↑ Ordnance Survey of Ireland: Rivers and their Catchment Basins 1958 (Table of Reference)

- ↑ Ninis.nisra.gov.uk

- ↑ "Sudden death may impact NI water". BBC News. 19 May 2005.

- ↑ "Earl of Shaftesbury does not rule out Lough Neagh sale". BBC News.

- ↑ Lough Neagh Boating Heritage Association

- 1 2 Hackney, P. 1992. Stewart & Corry's Flora of the North-east of Ireland. Third Edition. The Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast. ISBN 0 85389 446 9

- ↑ Official list of UK protected foods. Accessed 15 July 2011.

- ↑ Heaney, Seamus (1969). A Lough Neagh Sequence. Didsbury, England: Phoenix Pamphlet Poets Press. OCLC 1985783.

- ↑ Augusta, Lady Gregory. Part I Book III: The Great Battle of Magh Tuireadh. Gods and Fighting Men (1904) at Sacred-Texts.com.

- 1 2 3 Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. p.181

- 1 2 3 4 Mary McGrath, Joan C. Griffith. The Irish Draught Horse: A History. Collins, 2005. p.44

- ↑ Lough Neagh Heritage: Folklore & Legends

Further reading

- Wood, R.B.; Smith, R.V., eds. (1993). Lough Neagh: The Ecology of a Multipurpose Water Resource. Monographiae Biologicae. 69. Springer. ISBN 9780792321125.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lough Neagh. |

- Discover Lough Neagh

- Lough Neagh Heritage

- Lough Neagh Rescue

- BBC News on pollution

- BBC News on ownership of Lough Neagh

- Oxford Island National Nature Reserve