Lonsdaleite

| Lonsdaleite | |

|---|---|

|

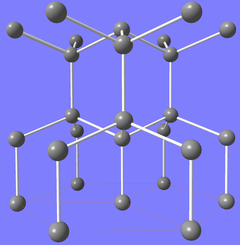

Crystal structure of lonsdaleite | |

| General | |

| Category | Mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | C |

| Strunz classification | 1.CB.10b |

| Crystal system | Hexagonal |

| Crystal class |

Dihexagonal dipyramidal (6/mmm) H-M symbol: (6/m 2/m 2/m) |

| Space group | P63/mmc |

| Unit cell | a = 2.51 Å, c = 4.12 Å; Z = 4 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Gray in crystals, pale yellowish to brown in broken fragments |

| Crystal habit | Cubes in fine-grained aggregates |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7–8 (for impure specimens) |

| Luster | Adamantine |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent |

| Specific gravity | 3.2 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+/-) |

| Refractive index | n = 2.404 |

| References | [1][2][3] |

Lonsdaleite (named in honour of Kathleen Lonsdale), also called hexagonal diamond in reference to the crystal structure, is an allotrope of carbon with a hexagonal lattice. In nature, it forms when meteorites containing graphite strike the Earth. The great heat and stress of the impact transforms the graphite into diamond, but retains graphite's hexagonal crystal lattice. Lonsdaleite was first identified in 1967 from the Canyon Diablo meteorite, where it occurs as microscopic crystals associated with diamond.[4][5]

Hexagonal diamond has also been synthesized in the laboratory (1966 or earlier; published in 1967)[6] by compressing and heating graphite either in a static press or using explosives.[7] It has also been produced by chemical vapor deposition,[8][9][10] and also by the thermal decomposition of a polymer, poly(hydridocarbyne), at atmospheric pressure, under argon atmosphere, at 1,000 °C (1,832 °F).[11][12]

It is translucent, brownish-yellow, and has an index of refraction of 2.40 to 2.41 and a specific gravity of 3.2 to 3.3. Its hardness is theoretically superior to that of cubic diamond (up to 58% more) according to computational simulations but natural specimens exhibited somewhat lower hardness through a large range of values (from 7 to 8 on Mohs hardness scale). The cause is speculated as being due to the samples having been ridden with lattice defects and impurities.[13]

The existence of lonsdaleite as a discrete material has been questioned, some evidence suggesting that what has been interpreted as lonsdaleite is instead cubic diamond dominated by structural defects.[14] A quantitative analysis of the X-ray diffraction data of lonsdaleite has shown that about equal amounts of hexagonal and cubic stacking sequences are present. Consequently, it has been suggested that "stacking disordered diamond" is the most accurate structural description of lonsdaleite.[15] On the other hand, recent shock experiments with in situ X-ray diffraction show strong evidence for creation of relatively pure lonsdaleite in dynamic high-pressure environments such as meteor impacts.[16]

Properties

According to the traditional picture, Lonsdaleite has a hexagonal unit cell, related to the diamond unit cell in the same way that the hexagonal and cubic close packed crystal systems are related. The diamond structure can be considered to be made up of interlocking rings of six carbon atoms, in the chair conformation. In lonsdaleite, some rings are in the boat conformation instead. In diamond, all the carbon-to-carbon bonds, both within a layer of rings and between them, are in the staggered conformation, thus causing all four cubic-diagonal directions to be equivalent; while in lonsdaleite the bonds between layers are in the eclipsed conformation, which defines the axis of hexagonal symmetry.

Lonsdaleite is simulated to be 58% harder than diamond on the <100> face and to resist indentation pressures of 152 GPa, whereas diamond would break at 97 GPa.[17] This is yet exceeded by IIa diamond's <111> tip hardness of 162 GPa.

Occurrence

Lonsdaleite occurs as microscopic crystals associated with diamond in several meteorites: Canyon Diablo, Kenna, and Allan Hills 77283. It is also naturally occurring in non-bolide diamond placer deposits in the Sakha Republic.[18] Material with d-spacings consistent with Lonsdaleite has been found in sediments with highly uncertain dates at Lake Cuitzeo,[19] in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico, by proponents of the controversial Younger Dryas impact hypothesis. Its presence in local peat deposits is claimed as evidence for the Tunguska event being caused by a meteor rather than by a cometary fragment.[20][21]

See also

- Aggregated diamond nanorod

- Glossary of meteoritics

- List of minerals

- List of minerals named after people

References

- ↑ Lonsdaleite on Mindat.org

- ↑ Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ Lonsdaleite data from Webmineral

- ↑ Frondel, C.; U.B. Marvin (1967). "Lonsdaleite, a new hexagonal polymorph of diamond". Nature. 214 (5088): 587–589. Bibcode:1967Natur.214..587F. doi:10.1038/214587a0.

- ↑ Frondel, C.; U.B. Marvin (1967). "Lonsdaleite, a hexagonal polymorph of diamond". American Mineralogist. 52.

- ↑ Bundy, F. P.; Kasper, J. S. (1967). "Hexagonal Diamond—A New Form of Carbon". Journal of Chemical Physics. 46 (9): 3437. Bibcode:1967JChPh..46.3437B. doi:10.1063/1.1841236.

- ↑ He, Hongliang; Sekine, T.; Kobayashi, T. (2002). "Direct transformation of cubic diamond to hexagonal diamond". Applied Physics Letters. 81 (4): 610. Bibcode:2002ApPhL..81..610H. doi:10.1063/1.1495078.

- ↑ Bhargava, Sanjay; Bist, H. D.; Sahli, S.; Aslam, M.; Tripathi, H. B. (1995). "Diamond polytypes in the chemical vapor deposited diamond films". Applied Physics Letters. 67 (12): 1706. Bibcode:1995ApPhL..67.1706B. doi:10.1063/1.115023.

- ↑ Nishitani-Gamo, Mikka; Sakaguchi, Isao; Loh, Kian Ping; Kanda, Hisao; Ando, Toshihiro (1998). "Confocal Raman spectroscopic observation of hexagonal diamond formation from dissolved carbon in nickel under chemical vapor deposition conditions". Applied Physics Letters. 73 (6): 765. Bibcode:1998ApPhL..73..765N. doi:10.1063/1.121994.

- ↑ Misra, Abha; Tyagi, Pawan K.; Yadav, Brajesh S.; Rai, P.; Misra, D. S.; Pancholi, Vivek; Samajdar, I. D. (2006). "Hexagonal diamond synthesis on h-GaN strained films". Applied Physics Letters. 89 (7): 071911. Bibcode:2006ApPhL..89g1911M. doi:10.1063/1.2218043.

- ↑ Nur, Yusuf; Pitcher, Michael; Seyyidoğlu, Semih; Toppare, Levent (2008). "Facile Synthesis of Poly(hydridocarbyne): A Precursor to Diamond and Diamond-like Ceramics". Journal of Macromolecular Science Part A. 45 (5): 358. doi:10.1080/10601320801946108.

- ↑ Nur, Yusuf; Cengiz, Halime M.; Pitcher, Michael W.; Toppare, Levent K. (2009). "Electrochemical polymerizatıon of hexachloroethane to form poly(hydridocarbyne): a pre-ceramic polymer for diamond production". Journal of Materials Science. 44 (11): 2774. Bibcode:2009JMatS..44.2774N. doi:10.1007/s10853-009-3364-4.

- ↑ Computational Methods and Experimental Measurements XV, by G. M. Carlomagno & C. A. Brebbia, WIT Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84564-540-3

- ↑ Nemeth, P.; Garvie, L.A.J.; Aoki, T.; Natalia, D.; Dubrovinsky, L.; Buseck, P.R. (2014). "Lonsdaleite is faulted and twinned cubic diamond and does not exist as a discrete material". Nature Communications. 5. doi:10.1038/ncomms6447.

- ↑ Salzmann, C.G.; Murray, B.J.; Shephard, J.J. (2015). "Extent of Stacking Disorder in Diamond". Diamond and Related Materials. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2015.09.007.

- ↑ Kraus, D.; Ravasio, A.; Gauthier, M.; Gericke, D.O.; Vorberger, J.; Frydrych, S.; Helfrich, J.; Fletcher, L.B.; Schaumann, G.; Nagler, B.; Barbrel, B.; Bachmann, B.; Gamboa, E.J.; Goede, S.; Granados, E.; Gregori, G.; Lee, H.J.; Neumayer, P.; Schumaker, W.; Doeppner, T.; Falcone, R.W.; Glenzer, S.H.; Roth, M. (2016). "Nanosecond formation of diamond and lonsdaleite by shock compression of graphite". Nature Communications. 7. doi:10.1038/ncomms10970.

- ↑ Pan, Zicheng; Sun, Hong; Zhang, Yi & Chen, Changfeng (2009). "Harder than Diamond: Superior Indentation Strength of Wurtzite BN and Lonsdaleite". Physical Review Letters. 102 (5): 055503. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102e5503P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.055503. PMID 19257519. Lay summary – Physorg.com (12 February 2009).

- ↑ Kaminskii, F.V., G.K. Blinova, E.M. Galimov, G.A. Gurkina, Y.A. Klyuev, L.A. Kodina, V.I. Koptil, V.F. Krivonos, L.N. Frolova, and A.Y. Khrenov (1985). "Polycrystalline aggregates of diamond with lonsdaleite from Yakutian [Sakhan] placers". Mineral. Zhurnal. 7: 27–36.

- ↑ Israde-Alcantara, I.; Bischoff, J. L.; Dominguez-Vazquez, G.; Li, H.-C.; Decarli, P. S.; Bunch, T. E.; Wittke, J. H.; Weaver, J. C.; et al. (2012). "Evidence from central Mexico supporting the Younger Dryas extraterrestrial impact hypothesis" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (13): E738–47. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E.738I. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110614109. PMC 3324006

. PMID 22392980.

. PMID 22392980. - ↑ Kvasnytsya, Victor; Wirth; Dobrzhinetskaya; Matzel; Jacobsend; Hutcheon; Tappero; Kovalyukh (August 2013). "New evidence of meteoritic origin of the Tunguska cosmic body". Planetary and Space Science. 84: 131–140. Bibcode:2013P&SS...84..131K. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2013.05.003. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Redfern, Simon. "Russian meteor shockwave circled globe twice". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

Further reading

- Anthony, J. W. (1995). Mineralogy of Arizona (3rd ed.). Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1579-4..

External links

- Mindat.org accessed 13 March 2005.

- Webmineral accessed 13 March 2005.

- Materials Science and Technology Division, Naval Research Laboratory website accessed 14 May 2006.

- Diamond no longer nature's hardest material

- lonsdaleite 3D animation