List of Santos-Dumont aircraft

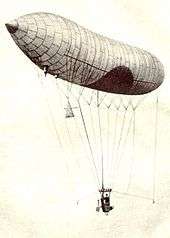

Basket and engine used in No. 1, 2 and 3

Through his career, aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont designed, built, and demonstrated a variety of aircraft — balloons, airships (dirigibles), monoplanes, biplanes, and a helicopter.

1898

Santos-Dumont No. 1

- Brésil (balloon) — Japanese silk envelope. 113 m3 (4,000 cu ft) capacity.[1]

- No. 1 (airship) — First flown on 18 September 1898. Had a cylindrical envelope with conical ends containing a ballonet connected to an air pump: 25 m (82 ft) long, 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in) diameter, 180 m3 (6,400 cu ft) capacity. A square basket was suspended from wooden battens contained in pockets in the envelope, and a silk-covered rudder fitted behind and above the basket. Powered by a 3 hp De Dion motor-cycle engine mounted outside and in front of the basket driving a small two bladed propeller. Fore and aft trim was achieved by moving a pair of ballast bags. Manoeuvred well, but the ballonet was too small to retain the necessary rigidity of the envelope, and loss of pressure caused it to be wrecked on its second flight on 20 September.[2][3]

1899

- No. 2 (airship) — An enlargement of No. 1, with a capacity of 200 m3 (7,100 cu ft).[4] On its first trial on 11 May 1899 it started to rain after inflation, cooling the hydrogen and so causing it to contract. The envelope began to fold in half and was then caught by a gust of wind and blown into nearby trees. It was not repaired.[5]

No. 3

- No. 3 (airship) — Shorter and of greater diameter than the preceding designs, intended to avoid the loss of shape caused by insufficient internal pressure that had led to their loss. 20.11 m (66.0 ft) long, 7.472 m (24 ft 6.2 in) diameter: capacity 500 m3 (18,000 cu ft). A bamboo keel was suspended from the envelope, under which the basket was suspended. No ballonet was fitted. Inflated with coal gas, not hydrogen

1900

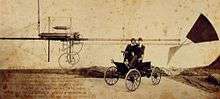

Keel of No. 4

- No. 4 (airship) — 39 m (128 ft) long, with a diameter of 5.1 m (17 ft) and a gas capacity of 420 m3 (15,000 cu ft).[6] No. 4 differed considerably from the previous models, not only in the shape of the envelope, but in the arrangement of the keel, which now carried the motor, a 7 h.p. Buchet, and pilot, who sat on a bicycle saddle. A tractor propeller was mounted at front of the keel. A ballonet and rotary pump was fitted, and Santos Dumont, having acquired a hydrogen generating plant, returned to hydrogen as a lifting gas.

- Engine later replaced by a 9 kW (12 hp) four-cylinder air-cooled unit, and envelope lengthened to 33 m (108 ft).[7]

1901

- No. 5 (airship) — Built to make an attempt on the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize for a flight from the Aero-Club de France's flying field at Saint-Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back within 30 minutes. Used the enlarged envelope from No. 4, from which an elongated triangular-section gondola made of pine was suspended. Other innovations included the use of piano wire to suspend the gondola, greatly reducing drag and the inclusion of water ballast tanks. Powered by a 12 hp 4-cylinder inline air-cooled engine driving a pusher propeller.[8] First flown on 11 July 1901: a lengthy flight was made the next day and an attempt on the de la Meurth prize on the 13th: the outward flight was accomplished in ten minutes, but the return was hampered by a headwind and took half an hour. On reaching St Cloud the engine failed and the arship was blown into the surrounding trees, damaging the envelope. A second attempt on the prize was made on 8 August but ended in disaster: after reaching the Tower in eight minutes, the airship began losing hydrogen because of a faulty valve. The partial deflation of the envelope caused some of the suspension wires to foul the propeller: Santo-Dumont therefore stopped the engine leaving the craft not only unpowered but without any means of inflating the ballonet to maintain the shape of the envelope. Helpless, the craft was blown back towards the Tower and blown onto the roof of the Trocadero Hotel, bursting the envelope with a noise described in some press reports an explosion but which Santos-Dumont likens to a paper bag being burst. Santos-Dumont was left precariously suspended above the courtyard of the hotel, but was rescued by the Paris fire brigade. The airship was damaged beyond repair: only the engine was salvaged.[9]

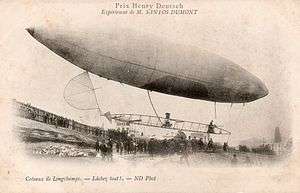

Santos-Dumont No. 6

- No. 6 (airship) — Construction started immediately after the loss of No. 5, and completed by early September. Similar to No. but with a larger envelope 22 m (72 ft 2 in) long and capacity of 622 m3 (22,000 cu ft) Won the Deutsch de la Meurth prize on 19 October 1901.

1902

- No. 7 (airship) — A fast competition airship, built to compete for the aviation prizes on offer at the 1904 St Louis World's Fair. Before the competitions the airships envelope was sabotaged, preventing him from competing.[10] Had a double-thickness varnished silk envelope, 50 m (160 ft) long, 7.92 m (26.0 ft) diameter: capacity 1260 m3 (44,500 ft3). It was powered by a 60 hp water-cooled engine, driving two propellers, one at the front and one at the rear of the gondola.,[11]

There was no "No. 8"; Santos-Dumont was superstitious about the number.

1903

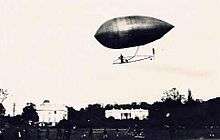

No. 9

- No. 9 Baladeuse — Built as the smallest airship that Santos-Dumont considered practical. As first constructed capacity was 220 m3 (7,800 cu ft): later enlarged slightly to 261 m3 (9,200 cu ft).[12]

Trial of No. 10 without the passenger gondola

- No. 10 (airship) — Sometimes called the Omnibus, this was intended to carry twelve passengers as well as the pilot and a second crew member. 48 m (157 ft 6 in) long, 8.5 m (27 ft 11 in) diameter, 2,010 m3 (71,000 cu ft) capacity. The pilot and the 46 hp four-cylinder Clément water-cooled engine, occupied a triangular-section uncovered gondola suspended 2 m (6 ft 7 in) below the envelope, with a fabric covered propeller at either end: a second gondola suspended 10 m (32 ft 9 in) below this held the three baskets for the passengers and an assistant pilot. Made only test flights.[13][14]

1905

- No. 11 (aeroplane)— Monoplane. First tested as a glider towed by a motor-boat: later fitted with a pair of propellers each driven by an engine.[15][16]

The No. 12 helicopter under construction

- No. 12 (helicopter)— Twin 6 m (19 ft 8 in) diameter rotors made of varnished silk stretched over a bamboo framework. Powered by a 25 hp Antoinette engine.[17]

- No. 13 (airship) — A curious composite craft, consisting of an ovoid hydrogen-filled envelope 19 m long, 14.5 m diameter and capacity 1902 m3, with a second conical envelope of 171 m3 attached underneath: this was filled with air which could be heated by a burner.[18]

1906

- No. 14 (airship) — As first built had a very elongated envelope 41 m long with a volume of 186 m3. Powered by a 14 2-cylinder Peugeot motorcycle engine: this was mounted on a balloon basket which was suspended from a bamboo keel which in turn was suspended from a length of bamboo inserted into a pocket in the underside of the envelope.[19] Subsequently considerably modified, with a shorter envelope and a short built-up gondola.[20]

- No. 14-bis (aeroplane) — Tail-forward (canard) biplane design; Flown to win the Aero-Club de France prize for the first officially observed flight of over 100 m (330 ft) on 12 November 1906. Tested by suspending it from the No.14 airship, hence its name.

1907

- No. 15 (aeroplane) — Tractor configuration biplane, powered by a 50 hp Antoinette engine mounted above the upper wing. High aspect ratio wings spanning 11 m with a chord of only 60 cm (2.0 ft), giving a surface area of 13 m2, divided into three bays by full-chord vertical surfaces. Pronounced dihedral like the 14bis, fitted with mid-gap ailerons in front of the wings. The wings were skinned with 3 mm Okoume plywood. Undercarriage consisted of a single wheel mounted at the junction of the forward lower wing spars and a tailskid. Biplane tail carried on a pair of bamboo booms placed one above the other and laterally braced to the wings by steel cables.[21] Damaged during taxying trials on 27 March 1907,: subsequently repaired and fitted with a 100 Antoinette V-16, but never flown successfully.[22]

No. 16

- No. 16 (hybrid airship) — 21 m long, 3 m diameter: capacity 99 m3. Fitted with a forward-mounted hexagonal elevator and a central 4 m span rectangular lifting surface, this was a hybrid airship incapable of flight relying solely on aerostatic buoyancy, instead requiring aerodynamic lift to fly. Tested unsuccessfully on 8 July 1907.[23]

- No. 17

- No. 18 — Not an aircraft, but a propeller-driven "hydro-flotteur" powered by V-16 Antoinette engine driving a three-bladed propeller, and resting on an elongated central float stabilised by smaller floats either side.[24]

- No. 19 Demoiselle

1908

- No. 20 Demoiselle — A modification of No. 19, considered to be the first practical ultralight aircraft.

1909

- No. 21 Demoiselle

- No. 22 Demoiselle

Notes

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p.46

- ↑ "Airship Pioneers". Flight: 957. 2 November 1916.

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, pp.77-81

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p.114

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p.117

- ↑ Santos Dumont 1904, pp.136-7

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p.137-8

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904,pp. 148-9

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, pp. 171-7

- ↑ "M. Santos Dumont's Airship". News. The Times (37433). London. 29 June 1904. col D, p. 10.

- ↑ "Airship Pioneers". Flight: 958. 2 November 1916.

- ↑ Santos-Dumont 1904, p. 285

- ↑ "Santos-Dumont, Aviateur". l'Aérophile (in French): 27. January 1906.

- ↑ "Les Prochaines Expériences de Santos-Dumont". l'Aérophile (in French): 200–4. September 1903.

- ↑ "Aeroplano Número 11" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "History of Santos-Dumont's Inventions". Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Santos-Dumont, Aviateur". l'Aérophile (in French): 27. January 1906.

- ↑ "Le Thermo-Balon de Santos-Dumont". l'Aérophile (in French): 20. January 1905.

- ↑ "Un Nouveau Racer Aérien". l'Aérophile (in French): 87–8. April 1905.

- ↑ "Le Santos-Dumont XIV á Trouville". l'Aérophile (in French): 200–1. September 1905.

- ↑ "Le Nouvel Aéroplane Santos-Dumont". l'Aérophile (in French): 92–4. April 1907.

- ↑ Gibbs-Smith, C. H. (1974). The Rebirth of European Aviation. London: HMSO. p. 237. ISBN 0 11290180 8.

- ↑ "Le Nouvel Engin de Santos-Dumont". l'Aérophile (in French): 161. June 1907.

- ↑ "Aeroplano Número 18". Retrieved 17 April 2014.

References

- Santos-Dumont, Alberto My Airships: The Story of My Life. London: Grant Rivers, 1904

This article is issued from Wikipedia - version of the 3/10/2016. The text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike but additional terms may apply for the media files.