Lisson Grove

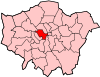

Coordinates: 51°31′31″N 0°10′11″W / 51.52539°N 0.16969°W

Lisson Grove is a district and a street of the City of Westminster, London, just to the north of the city ring road. There are many landmarks surrounding the area. To the north is Lord's Cricket Ground in St John's Wood. To the west are Little Venice, Paddington and Watling Street. To the north east is Primrose Hill and south east is Marylebone, which includes the railway station and Dorset Square, the original home of the Marylebone Cricket Club. It is west of the London Planetarium, Madame Tussaud's, Baker Street and Regent's Park. The postal districts are NW1 and NW8.

History

Lisson Green is described as a hamlet in the Domesday book in 1086, the edges of the settlement defined by the two current Edgware Road stations facing onto Edgware Road or Watling Street as it was previously known, one of the main Roman thoroughfares in and out of London. Occasionally referred to as Lissom Grove, originally Lisson Grove was part of the medieval manor of Lilestone which stretched as far as Hampstead. Lisson Green as a manor broke away c. 1236 with its own manor house. Paddington Green formed part of the original Lilestone estate

One of Lisson Green village's first attractions would have been the Yorkshire Stingo, a public house probably visited by Samuel Pepys in 1666 on a visit with a flirtatious widow. Stingo was the name of a particular Yorkshire ale. On Saturdays during the 1780s, lascars, former sailors from Bengal, Yemen, Portuguese Goa employed by the East India Company left stranded and destitute in London would gather to receive a small subsidy.

1700s

Until the late 18th century the district remained essentially rural. The Austrian composer Joseph Haydn moved briefly to a farm in Lisson Grove in the spring of 1791 in order to have quiet surroundings in which to compose during his three-year stay in England. The historical painter Benjamin Haydon described a Lisson Grove dinner party with William Wordsworth, John Keats and Charles Lamb at which Lamb got drunk and berated the ‘rascally Lake poet’ for calling Voltaire a dull fellow.[1]

1800s

Nowadays Lisson Grove is a much improved section of West London, but for over a hundred years it was one of the capital's worst slums.[2] The area was notorious for drinking, crime and prostitution, as well as the extreme poverty of the people and the squalor and dilapidation of the homes they lived in. Local police officers only patrolled the district in pairs, and they described the women of the area as the most drunken, violent and foul-mouthed in all London.[3] The Grove being between Marylebone and Paddington railway stations, and on top of a busy midsection of Regent's Canal, the industrialisation of the area was swift during the 19th century transforming the area from a pastoral outpost on the north western edge of London into a crossroads for goods, cargo and passengers.

Regent's Canal arrived in rural Lisson Grove in 1810 and with the construction of Eyre's Tunnel or Lisson Grove Tunnel under Aberdeen Place in 1816 and Marylebone railway station by H W Braddock for the Great Central Railway on the Portman Nursery site at the end of the century, the rural Lisson Grove was quickly engulfed by the expanding city during the 1800s.[4]

The Regency Era (1811–1820): William Blake, the Shoreham Ancients and The Brazen Head public house

It was during the early 1800s that painters from the Royal Academy, including a coterie of various student artists calling themselves the Shoreham Ancients inspired and congregating around William Blake, began to settle in and around Lisson Grove. In 1812, John Linnell, who was to become a major patron of Blake's work, visited his friend Charles Heathcote Tatham, an architect who had built himself a majestic house in the open fields of the area of Lisson Grove between Park Road and Lisson Grove (the road) to paint the view of the surrounding fields of his garden.[5] No. 34 Alpha Cottages is memorialised in the name of a block of flats on Ashmill Street, opposite Ranston (formerly Charles) Street and Cosway Street.

One such friend and colleague of Blake was Richard Cosway whose studio on Stafford Street was renamed as Cosway Street. "Cosway was not only a famous and fashionable painter; he was also a mesmerist and magician who practised arcana related to alchemical and cabbalistic teaching. There are reports of erotic ceremonies, the imbibing of drugs or 'elixirs', and ritual nudity. Blake was no stranger to the symbols or beliefs of a man such as Cosway – the manuscript of the poem he was writing contains many drawings of bizarre sexual imagery, including women sporting giant phalli and children engaged in erotic practices with adults."[6]

In 1829 the Catholic church of Our Lady was built. Designed by J.J. Scoles in the new Gothic style, it was one of the first Catholic churches following the Catholic Emancipation Act. Nearby on Harewood Avenue the Convent of the Sisters of Mercy was also established as part of the Catholic Mission in St. John's Wood, serving the large Irish community attracted by the railway, canal and construction work. The same year George Shillibeer operated the first London omnibus from the Yorkshire Stingo taking passengers to Bank.

Lisson Grove hosted the first of London's Victorian Turkish baths—which were to become a fashionable trend towards the latter half of the 19th century—when Roger Evans established one in 1860 at his house on Bell Street.[7]

A critical social commentary reads:

This is the side of Lisson Grove which is supposed to contain the decent poor; and on the other side, in the streets leading into the Edgeware Road, is a more densely crowded and even lower population. Bell Street, now famous in history as the spot where Turkish baths were first established, is the main stream of a low colony, with many tributary channels. There is no particular manufacture in the neighbourhood to call the population together; a great number are not dependent upon St. John's Wood or the Regent's Park for a living; and they come together simply because they like the houses, the rents, the inhabitants, and the general tone of living in the settlement.— John Hollingshead, 'Social London', 1861, [8]

Hollingshead was, of course, referring only to the first such bath in London. The first Victorian Turkish bath was actually built near Cork in Ireland in 1856, while the first in England opened in Manchester in 1857.[9]

During the latter part of the 19th century a number of artisans and workers' flats and cottages sprang up from social housing initiatives spearheaded by Octavia Hill and the Peabody Trust. Across the road from The Green Man Inn, in 1884 Miles Building was built by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Association, facing Bell Street and Penfold Place.

The lost North Bank and South Bank Nash villas

John Nash as a director of the Regent's Canal Company formed in 1812 began building detached villas set in gardens facing onto either side of the section of the canal running parallel to Lodge Road. Ultimately destroyed in 1900 in order to make way for St John's Wood electricity sub-station (North Bank) and Lisson Grove housing estate (South Bank) the enclave of distinctive white villas bisected by the picturesque banks of the canal attracted a literary and journalist set such as George Eliot, along with East India Dock Company employees with a working interest in being near the villas along Lodge Road.

"North and South Bank, have charming, if somewhat dilapidated streets of small villas standing in their own gardens, that ran down to the water and towpath either side of the canal. Incidentally these streets, owing to the eccentricities of some of the inhabitants, and the secrecy provided by the high walls of the gardens, had acquired a somewhat sinister reputation."[10] In 1836 the North Bank was mentioned as being associated with scandal in a local history 'at this point the East India Dock Company whose employees were fairly thick on the ground in St John's Wood'.

While Nash was developing his villas in the north east of Lisson Grove, nearest Regent's Park, Sir Edward Baker (who gave his name to Baker Street) acquired the southern part of Lisson Green in 1821 and built large blocks of flats as an extension of Marylebone.[11] From 1825 Sir Edwin Landseer moved to No 1, St John's Wood Road on the corner of Lisson Grove in a small cottage on the site of Punker's Barn. The journalist George Augustus Henry Sala born in 1828, recalls growing up in Lisson Grove during the 1830s "when the principle public buildings were pawnbrokers, and 'leaving shops', low public houses and beershops and cheap undertakers."

1885: The Eliza Armstrong Scandal

The fictional Eliza Doolittle was born and raised in Lisson Grove and had to pay "four and six a week for a room that wasn't fit for a pig to live in" before coming under the tutelage of Professor Henry Higgins. These characters from George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion are best known to modern audiences from the Lerner and Loewe musical and film adaptation of the play, entitled My Fair Lady. In 1885 the case of 13-year-old Eliza Armstrong, who was sold to a brothel keeper for £5, caused such an outcry that the law was changed and so was the name of the street where she lived (from Charles Street to Ranston Street), such was the dishonourable reputation it had gained.[11]

In 1890 construction began on Marylebone Railway, completing almost a decade later in 1899. In 1894 Landseer's house was destroyed to make way for railway artisan homes. Penfold Street was to become dominated by the Great Central Goods Depot Yard,[12] along which a number of public houses sprang up: the Lord Frampton (now residential flats), the Richmond Arms and The Crown Hotel (known as Crocker's Folly since 1987). In 1886–96 the newly named Ranston Street saw a number of Almond & St Botolphs Cottages (nos. 14–19) built under the initiative of social reformer Octavia Hill.[13] As a strong advocate of small scale housing, cottages and mixed developments, she described these cottages as an experimental form of 'compound housing' e.g. maisonettes in her 1897 Letter to Fellow Workers.

In 1897, local entrepreneur Frank Crocker, who also owned The Volunteer in Kilburn, had architect H.C. Worley of Welbeck Street draw up plans for an ornately eclectic public house The Crown Hotel, to be renamed Crocker's Folly from 1987, on the corner of Aberdeen Place and Cunningham Place, housing several Saloon bars on the ground floor with a hotel, dining rooms and a concert room on the floors above.[14] Grade II* listed, it is currently under refurbishment as at September 2013.

1900s

In 1903 the Home for Female Orphans[15] was situated on the corner of Lisson Grove and St John's Wood Road. In November 1906 Henry Sylvester Williams (b.1867 – d.1911), a Trinidadian lawyer, anti-slavery and civil rights campaigner was elected to the Marylebone Council for Church Street Ward as the first black councillor in Westminster. A green plaque at 38, Church Street marks where Williams lived during 1906 -1908. Edgware Road (Bakerloo line) underground station opened in 1907 in a narrow parade of shops, with exits onto Edgware Road and Bell Street.

Following World War One, Lloyd George announced "homes fit for heroes" leading to a housing boom from which Lisson Grove was to benefit. In 1924, Fisherton Street estate was completed by St Marylebone Council with seven apartment blocks in red-brick neo-Georgian style with high mansard roofs grouped around two courtyards. Noted for their innovation at the time for being some of the first social housing to include an indoor bathroom and toilet, in 1990 the estate was defined as the Fisherton Street Conservation Area[16] The blocks were named mostly for the notable former residents of Lisson Grove and its surrounding areas, which drew Victorian landscape painters, sculptors, portraitists and architects:

- Lilestone: Named in reference to the medieval manor stretching to Hampstead before Lisson Grove became a separate manor in the 13th century

- Huxley: Thomas Henry Huxley the self-taught biologist and ardent Charles Darwin supporter was resident at 41 North Bank during the 1850s.

- Gibbons: Grinling Gibbons (1648–1721) a master carver who worked on St Pauls

- Landseer: Sir Edwin Landseer (famous for sculpting the lions in Trafalgar Square)

- Capland:

- Frith: For sculptor William Silver Frith (1850–1924)

- Orchardson: For painter Sir William Quiller Orchardson (1832–1910)

- Dicksee: For Sir Francis Dicksee, a noted Victorian painter

- Eastlake: For Charles Eastlake (1836–1906) British architect and furniture designer

- Tadema: For Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

- Poynter: For Sir Edward Poynter (1836–1919)

- Stanfield: George Clarkson Stanfield and his son, both artists.

- Frampton: George Frampton the sculptor had lived nearby at Carlton Hill from 1910 and may have given his name to Frampton Street and Frampton House

- Wyatt: Matthew Cote Wyatt who lived at Dudley Grove House, Paddington

After the First World War dining rooms at 35 Lisson Grove became a fish bar, called the Sea Shell from 1964. Now on the corner of Shroton Street, the restaurant is one of London’s most highly rated fish and chip shops.

In 1960 the first Labour Exchange was established on Lisson Grove to much fanfare,[17] and was late to take its place in punk music history as the place where Joe Strummer was to meet fellow The Clash member.

Notable former residents

- Charles Rossi sculptor at 21, Lisson Grove, 1810

- Leigh Hunt, resided at 13, Lisson Grove North on his release from Horsemonger Prison in 1815 and was visited on many occasions by Lord Byron here[18]

- Benjamin Haydon, painter at 21 Lisson Grove, 1817, tutor of Edwin Landseer and his brother

- Sir Edwin Landseer (1802–1873) and various members of his family congregated to live at Cunningham Place. From 1825 he first lived at 1, St John's Wood Road on the corner of Lisson Grove in a small cottage on the site of Punker's Barn. This was later demolished in 1844 to make place for a small but "rather aristocratic" house (built by Thomas Cubitt, who also built Osborne House on the Isle of Wight for Queen Victoria). The Cubitt designed house was later demolished in 1894 to make way for artisan workers homes built by the railway arranged as Wharncliffe Gardens.

- Henry Willams Banks Davis lived at 10a Cunningham Place, a property adjacent to Landseer's studios, which Davis moved into

- George Augustus Henry Sala, journalist, born in 1828, recalls growing up in Lisson Grove during the 1830s "when the principle public buildings were pawnbrokers, and 'leaving shops', low public houses and beershops and cheap undertakers."

- Catherine Sophia Blake William Blake's widow lived from 1828–1830, at 20 Lisson Grove North, London (renumbered 112 Lisson Grove, London NW1) as housekeeper to Frederick Tatham. (Original building demolished.)

- Samuel Palmer, landscape painter and etcher lived at 4, Street, Lisson Grove, Marylebone[19]

- Mary Shelley moved to North Bank, 28 March 1836 for one year with her son

- Thomas Henry Huxley: Resident at North Bank during the 1850s

- James Augustus St John moved in 1858 from North Bank to Grove End Road

- Dr Southwood Smith moved to Lisson Grove in 1859 to work at the London Fever Hospital. Smith's granddaughter Octavia Hill, who he brought up, was later to live at 190, Marylebone Road becoming a founder of the Peabody Trust and have a great impact on the social housing movement evident in Lisson Grove from 1890s onwards.

- Blue Plaque: Emily Davies, founder of Girton College, Cambridge lived at 17, Cunningham Place[20] from 1863 to 1875 with her mother.

- George Eliot and her husband bought The Priory, 21 North Bank in 1863 and held many of her Sunday receptions during the 17 years she spent there until 1880.

- William Henry Giles Kingston born in London, 1814 at Harley Street, lived at No. 6, North Bank

- Jerome K. Jerome attended The Philological School, now Abercorn School on the corner of Lisson Grove and Marylebone Road during the early 1870s.

- Arthur Machen at Edward House, 7 Lisson Grove during World War One until the 1920s.[21]

- A newly married 28-year-old Agatha Christie rented 5, Northwick Terrace during 1918–1919

- Blue Plaque: Guy Gibson V.C, leader of the Dambusters raid lived at 32, Aberdeen Place between 1918–1944.[22]

Arts and antiques

The area has a long association with art, artists and theatre. In 1810 the Royal Academy catalogues give sculptor Charles Rossi's address as 21 Lisson Grove, where he had bought a large house. By 1817, Rossi was renting out a section of the house to painter Benjamin Haydon. A blue plaque on the corner of Rossmore Road and Lisson Grove marks the spot and in 2000 author Penelope Hughes-Hallett wrote The Immortal Dinner with the focus on Haydon's dining companions invited to his Lisson Grove abode on 28 December 1817.[23] Haydon's protégé Edwin Landseer lived north on Lisson Grove on the corner of St John's Wood Road from 1825.

The arrival of Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema at nearby 44, Grove End Road in the late 1870s inspired the naming of one of the Lilestone Estate apartment blocks built in the 1920s as Tadema House.[24] Eastlake House, situated opposite Tadema House, is possibly named for Charles Eastlake whose Eastlake Movement's underlying ethos of simple decorative devices that were affordable and easy to keep clean would have been of interest to those developing social housing in the 20th Century.

On Bell Street, the Lisson Gallery, established in 1967 by Nicholas Logsdail, championed the new British sculptors of the 1980s and continues to show new and established artists, with expanded premises further along Bell Street. Mark Jason Gallery at No 1 Bell Street specialises in promoting contemporary British and international artists.[25] At No 17, Bell Street Vintage Wireless London has existed since 1979, selling a wide assortment of vintage turntables, radiograms, wirelesses, dansettes, reel-to-reels, amps and mikes.

In 2006 the Subway Gallery arrived in Joe Strummer's subway (an underpass for crossing beneath the Marylebone Road). Conceived by artist Robert Gordon McHarg III, the space itself is a 1960s kiosk with glass walls which creates a unique showcase for art, interacting naturally with passers by, visitors and the local community.[26]

The Show Room is on Penfold Street, next to the main Aeroworks factory. The Show Room[27] is a non-profit space for contemporary art that is focused on a collaborative and process-driven approach to production, be that artwork, exhibitions, discussions, publications, knowledge and relationships.

Church Street runs parallel to St John's Wood Road and plays host to a varied market Mondays–Saturdays, 8am–6pm selling fruit and vegetables, clothes, and bags amongst other items.[28] Towards the Lisson Grove end of Church Street is Alfie's Antique Market,[29] London's largest indoor market for antiques, collectables, vintage, and 20th century design is in the former Jordans Department Store, decorated with an Egyptian art deco theme similar to the Aeroworks – the indoor market, "houses more than 200 permanent stall holders and covers in excess of 35,000 sq ft of shop space on five floors."[30] Opened in 1976 by Bennie Gray, in the then derelict department store, the Antiques Market has since spawned twenty or so individual shops at the Lisson Grove end of Church Street specialising in mainly 20th-century art and collectables

Architectural Landmarks

- Grade II Listed Victorian 1897 public house Crocker's Folly

- Fisherton Estate Conservation Area

- In 1983, Jeremy Dixon (later of Dixon Jones' fame with fellow architect Edward Jones) designed a series of terrace houses on Ashmill Street.

- Between Hatton Street and Penfold Street the old Spitfire Palmers Aeroworks Factory[31] in operation from 1912 – 1984 manufacturing aircraft components including stand outs as a white Egyptian Art Deco landmark, the elevation facing onto Penfold Street having formerly been a furniture store. This was redeveloped by Terry Farrell in 1985-8 and includes their architectural practice. Next to the Aeroworks, another of the lower buildings now houses The Show Room.

Theatres and music halls

The Metropolitan Music Hall, re-launched with great refurbishment and extended capacity in 1867, was situated at 267, Edgware Road, opposite Edgware Road (Bakerloo) tube station entrance/exit and Bell Street.[32] Paddington Green police station is now situated on this spot, having moved to make way for the Marylebone flyover.

The Royal West London Theatre was on Church Street, a commemorative plaque above the Church Street Library marking its place.[33] From 1904 onwards Charlie Chaplin trod the boards as a teenager.

Currently Lisson Grove has two theatres.

The Cockpit Theatre on Gateforth Street is a purpose built fringe theatre venue promoting "Theatre of Ideas and ensemble working. Its regular classes and workshops, comfortable bar and friendly team enable this creative hub to support performers, the industry, diverse audiences, the local community and free radicals alike."[34]

The Schmidt hammer lassen-designed City of Westminster College at 25 Paddington Green contains the Siddons Theatre, named for the much acclaimed 18th century tragedienne Sarah Siddons, buried at St Mary on Paddington Green.

Places of worship

Christ church, Cosway Street, designed by Thomas Hardwick in 1822–24 and closed in 1973, now used as business premises.[35] and kurds are 90% and they are musilm sunni

Parks and playgrounds

- Broadley Street Gardens

- Fisherton Street Estate Playground

Education

There a number of nurseries in Lisson Grove, two run by London Early Years Foundation (LEYF) at Luton Street and Lisson Green.

Primary Schools are St. Edward's Catholic Primary School, Gateway Academy on Gateforth Street and King Solomon Primary.

King Solomon Academy, an ARK school, was recently established on the site of the former Rutherford School for Boys. The main building of the secondary school is Grade II* listed, designed by Leonard Manasseh and Ian Baker in 1957 and completed in 1960. Mannaseh's style has been characterised as displaying a digested influence of Le Corbusier with traits including "crispness", glazed or tiled pyramids (see the inverted pyramid on the roof of the school and the Egyptian sculpture garden), window walls with fine black mullions, assertive gables, and Baker’s bold geometrical masonry forms, and grand symmetry and rhythms. The interior lobby is lined in Carrara marble, with corridors lined in Ruabon tiles.[36] When asked "Why the marble, Mr Manasseh?" he was reported as saying "Because it's boy-proof."[37]

Public houses

- The Brazen Head

Not a particularly popular name for a public house, this was named for the magical artefact, a speaking brass head, 13th century Friar Roger Bacon created, and the subject of legend circulating in the 16th century. The most famous Brazen Head features in James Joyce's Ulysses.

- The Green Man (corner of Bell Street and Edgware Road, W2)

The legend is that the pub is named for a herbalist had lived on the site of the pub, due to the nearby spring which had curative properties. Noted for the eye lotion produced from the spring water, all subsequent leaseholders were obliged to sign a clause requiring them to offer the eye lotion for free on request, in his memory.

As recently as 1954 Stanley Coleman wrote in his 'Treasury of Folklore: London' "that you may ask [at the bar] for eye lotion and the publican will measure you out an ounce or two" though it no longer came from the well in the cellar which had dried up when Edgware Road Tube station had been built on the site.[38]

- The Constitution

- The Lord High Admiral

- The Richmond Arms

- The Perseverance

Transport

National rail

Tube stations

The nearest London Underground stations are Baker Street, Edgware Road (Bakerloo line), Edgware Road (Circle, District and Hammersmith & City lines), Paddington station, Warwick Avenue and Marylebone.

Bus routes

Bus routes serving the road Lisson Grove are 139 (West Hampstead to Waterloo via Trafalgar Square), 189 (Brent Cross to Oxford Street).[39]

Edgware Road bus stops for Lisson Grove are served by bus routes 16, 6, 98, 414.[40]

Crime

The nearby Lisson Green estate has gone through vital regeneration which saw a huge drop in crime. The estate was a no go area in the 90s and early 2000s due to robberies, drug dealing, violence and gang related activity. The local ward (Church Street) was named the most deprived in London and the South East of England in 2004.

The street gang in the area known as the Lisson Green Mandem are thought to be one of the earliest gang in the area (although the names might have been different before). Police know the gang have altercations with other gangs nearby – Mozart SMG, ASA, Warwick Boys, and the Horror Road Alliance.

The murder of Jevon Henry in 2007 saw five men from the estate jailed for life. It was thought to be a drugs dispute between the two main gangs from the area. One of the gang which is predominantly Bangladeshi youths and another gang which was predominately Black youths.

Jevon Henry, 18, died in January 2007 from a single stab wound to the heart after being set upon by the five men in the Lisson Green Estate in Marylebone. Kamal Abdul, 21, Muhid Abdul, 25, Jubed Miah, 26, Toufajul Miah, 21 and Taz Uddin, 22, must serve minimum terms of up to 19 years.

A witness saw one of the men strike Jevon with a hammer, jurors heard. She called out in an attempt to make the attacker flee, before leaving the scene briefly to phone 999. When she returned she saw Jevon stagger across a car park before collapsing. He died of his injuries in St Mary's Hospital the next day.

Thugs from the estate are thought to have committed rioting and looting throughout the riots in August 2011. They teamed up with the Ladbroke Grove Bloods to cause havoc throughout west London. The 70 strong gang set off along Queensway, kicking their way into a Gala Casino as staff tried to push a sofa against the glass doors to block their entry. In CCTV footage, one member of staff can be seen trying to fight the yobs off with an umbrella, before fleeing into a back room. One worker had his arm broken by one of the attackers, who stole cash from behind the counter. 16 youths were arrested.

References

- ↑ "haydon - immortal dinner". Teaching.shu.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Thomas Beames, The Rookeries of London, Frank Cass, 1970.

- ↑ The Quiver, 1896–1897.

- ↑ "North Marylebone: History | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Linnell, John. "Tatham's Garden, Alpha Road at Evening, 1812". Tate. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ↑ Ackroyd, Peter. Blake. Sinclair-Stevenson. p. 210.

- ↑ "VICTORIAN TURKISH BATHS: their arrival in 19th century London. Pt 3: The first in London.". Victorianturkishbath.org. 2001-04-17. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Publications - Social Investigation/Journalism - Ragged London in 1861, by John Hollingshead, 1861 - The North". Victorian London. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ↑ Shifrin, Malcolm (2015). Victorian Turkish Baths. Historic England. ISBN 978-0-521-53453-6.

- ↑ Smith, Cecil (1942). A Short History of St John's Wood.

- ↑ "The City's Waterways". London Canals. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Barras, Jamie (2009-04-21). "Almond & St Botolph's Cottages NW1 | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Historic Pub Interiors". Heritagepubs.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/Collections-Research/Research/Your-Research/X20L/objects/record.htm?type=object&id=288971. Retrieved 1 September 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Fisherton Street Conservation Area" (PDF). Transact.westminster.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ↑ "50 Years Progress - British Pathé". Britishpathe.com. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Wheatley, Henry. London Past & Present: Its History Associations & Traditions.

- ↑

- ↑ Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "MIND: A Quartlery Review of Psychology and Philosophy 1919". Aberdeen University. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Immortal Dinner by Penelope Hughes-Hallett (Viking 2000)

- ↑ "Collage". Collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Introduction". Mark Jason Gallery. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Home". Subwaygallery.com. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Showroom". Showroom. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Archived 3 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Alfies Antique Market". Alfiesantiques.com. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Have a good old time". Telegraph. 2001-03-17. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "The Spitfire Works, Penfold Street, London, UK". Manchesterhistory.net. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "The Metropolitan Theatre, 267 Edgware Road, Paddington". Arthurlloyd.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Fallon, Patricia (2010-03-18). "West London Theatre | Then and now | Topics". Church Street Memories. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "The Cockpit". The Cockpit. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Christ Church Cosway Street, Marylebone - Bob Speel's website". Speel.yme.uk. 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Managing the Arts in the Curriculum - Michael Marland, Rick Rogers - Google Books". Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ↑ Brittain-Catlin, Timothy (2011). Leonard Manasseh & Partners. RIBA Publishing.

- ↑ Simpson, Jacqueline. Green Men and White Swans: The Folklore of British Pub Names. p. 121.

- ↑ "Home - Transport for London" (PDF). Tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ "Home - Transport for London" (PDF). Tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

Further reading

Pineapples and Pantomimes: A History of Church Street and Lisson Green, Westminster Libraries, 1992, E McDonald and D J Smith

External links

- LondonTown.com information

- Church Street Neighbourhood Centre

- North Paddington Guide

- Alfie's Antique Market

- Francesca Martire: 36, Church Street

- Designs for Discerning Rebels

- Decoratum: 31–33, Church Street

- Vincenzo Caffarella

- Deborah Woolf Vintage: 28, Church Street

- St. Edward's Catholic Primary School – Parent Teacher Association