Linear A

| Linear A | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type |

Undeciphered (presumed syllabic and ideographic)

|

| Languages | 'Minoan' (unknown) |

Time period | 2500–1450 B.C.E.[1] |

| Status | Extinct |

Child systems | Linear B, Cypro-Minoan syllabary[2] |

Sister systems | Cretan hieroglyphs |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Lina, 400 |

Unicode alias | Linear A |

| Final Accepted Script Proposal | |

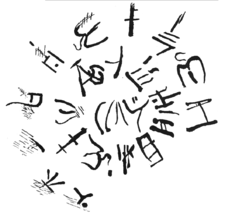

Linear A is one of two currently undeciphered writing systems used in ancient Greece (Cretan hieroglyphic is the other). Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It was discovered by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. It is the origin of the Linear B script, which was later used by the Mycenaean civilization.

In the 1950s, Linear B was largely deciphered and found to encode an early form of Greek. Although the two systems share many symbols, this did not lead to a subsequent decipherment of Linear A. Using the values associated with Linear B in Linear A mainly produces unintelligible words. If it uses the same or similar syllabic values as Linear B, then its underlying language appears unrelated to any known language. This has been dubbed the Minoan language.

Script

Linear A has hundreds of signs. They are believed to represent syllabic, ideographic, and semantic values in a manner similar to Linear B. While many of those assumed to be syllabic signs are similar to ones in Linear B, approximately 80% of Linear A's logograms are unique;[3][4] the difference in sound values between Linear A and Linear B signs ranges from 9% to 13%.[5] It primarily appears in the left-to-right direction, but occasionally appears as a right-to-left or boustrophedon script.

An interesting feature is that of how numbers are recorded in the script. The highest number that has been recorded is 3000, but there are special symbols to indicate fractions and weights.

Corpus

Linear A has been unearthed chiefly on Crete, but also at other sites in Greece, as well as Turkey and Israel. The extant corpus, comprising some 1427 specimens totalling 7362–7396 signs, if scaled to standard type, would fit on a single sheet of paper.[6]

Crete

According to Ilse Schoep, the main discoveries of Linear A tablets have been at three sites on Crete:[7]

Haghia Triadha in the Mesara with 147 tablets; Zakro/Zakros, a port town in the far east of the island with 31 tablets; and Khania/Chania, a port town in the northwest of the island with 94 tablets.

Discoveries have been made at the following locations on Crete:

- Apoudoulou

- Archanes

- Arkalochori

- Armenoi

- Chania

- Gournia

- Hagia Triada (largest cache)

- Kardamoutsa

- Kato Simi (also spelled Kato Syme)

- Knossos

- Kophinas

- Larani

- Mallia

- Mochlos (also spelled Mokhlos)

- Mount Juktas (also spelled Iouktas)

- Myrtos Pyrgos

- Nerokourou

- Palaikastro

- Petras

- Petsophas

- Phaistos

- Platanos

- Poros, Heraklion

- Prassa

- Pseira

- Psychro (also spelled Psykhro)

- Pyrgos Tylissos

- Sitia

- Skhinias

- Skotino cave

- Traostalos

- Troulos (or Trulos)

- Vrysinas

- Zakros

Outside of Crete

Prior to 1973, only one Linear A tablet was known to be found outside of Crete (on Kea).[8] Since then, other locations yielded inscriptions.

According to Finkelberg, most—if not all—inscriptions found outside of Crete were made locally. This is indicated by such factors as the composition of the material on which the inscriptions were made.[8] Also, close analysis of the inscriptions found outside of Crete indicates the use of a script that is somewhere in between Linear A and Linear B, combining the elements of both.

Other Greek islands

Mainland Greece

Chronology

Linear A was a contemporary and possible child of Cretan hieroglyphs and the ancestor of Linear B. The sequence and the geographical spread of Cretan hieroglyphs, Linear A and Linear B, the three overlapping, but distinct writing systems on Bronze Age Crete and the Greek mainland can be summarized as follows:[10]

| Writing system | Geographical area | Time span[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|

| Cretan Hieroglyphic | Crete | c. 2100 – 1700 BCE |

| Linear A | Aegean islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), and Greek mainland (Laconia) | c. 2500 – 1450 BCE |

| Linear B | Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) | c. 1450 – 1200 BCE |

Discovery

Archaeologist Arthur Evans named the script "Linear" because its characters consisted simply of lines inscribed in clay, in contrast to the more pictographic characters in Cretan hieroglyphs that were used during the same period.[11]

Several tablets inscribed in signs similar to Linear A were found in the Troad. While their status is disputed, they may be imports, as there is no evidence of Minoan presence in the Troad. Classification of these signs as a unique Trojan script (proposed by contemporary Russian linguist Nikolai Kazansky) is not accepted by other linguists.

Theories of decipherment

It is difficult to evaluate a given analysis of Linear A as there is little point of reference for reading its inscriptions. The simplest approach to decipherment may be to presume that the values of Linear A match more or less the values given to the deciphered Linear B script, used for Mycenaean Greek.[12]

Greek

In 1957, Bulgarian scholar Vladimir I. Georgiev published his Le déchiffrement des inscriptions crétoises en linéaire A ("The decipherment of Cretan inscriptions in Linear A") stating that Linear A contains Greek linguistic elements.[13] Georgiev then published another work in 1963, titled Les deux langues des inscriptions crétoises en linéaire A ("The two languages of Cretan inscriptions in Linear A"), suggesting that the language of the Hagia Triada tablets was Greek but that the rest of the Linear A corpus was in Hittite-Luwian.[13][14] In December 1963, Gregory Nagy of Harvard University developed a list of Linear A and Linear B terms based on the assumption "that signs of identical or similar shape in the two scripts will represent similar or identical phonetic values"; Nagy concluded that the language of Linear A bears "Greek-like" and Indo-European elements.[15]

Distinct Indo-European branch

According to Gareth Alun Owens, Linear A represents the Minoan language, which Owens classifies as a distinct branch of Indo-European potentially related to Greek, Sanskrit, Hittite, Latin, etc.[16][17] At "The Cretan Literature Centre", Owens stated:[18]

″Beginning our research with inscriptions in Linear A carved on offering tables found in the many peak sanctuaries on the mountains of Crete, we recognise a clear relationship between Linear A and Sanskrit, the ancient language of India. There is also a connection to Hittite and Armenian. This relationship allows us to place the Minoan language among the so-called Indo-European languages, a vast family that includes modern Greek and the Latin of Ancient Rome. The Minoan and Greek languages are considered to be different branches of Indo-European. The Minoans probably moved from Anatolia to the island of Crete about 10,000 years ago. There were similar population movements to Greece. The relative isolation of the population which settled in Crete resulted in the development of its own language, Minoan, which is considered different to Mycenaean. In the Minoan language (Linear A), there are no purely Greek words, as is the case in Mycenaean Linear B; it contains only words also found in Greek, Sanskrit and Latin, i.e. sharing the same Indo-European origin."

Luwian

Since the late 1950s, a theory based on Linear B phonetic values suggests that Linear A language could be an Anatolian language, close to Luwian.[19] The theory for the Luwian origin of Minoan, however, failed to gain universal support for the following reasons:

- There is no remarkable resemblance between Minoan and Hitto-Luwian morphology.

- None of the existing theories of the origin of Hitto-Luwian peoples and their migration to Anatolia (either from the Balkans or from the Caucasus) are related to Crete.

- There was a lack of direct contact between Hitto-Luwians and Minoan Crete; the latter was never mentioned in Hitto-Luwian inscriptions. Small states located along the western coast of ancient Asia Minor were natural barriers between Hitto-Luwians and Minoan Crete.

- Obvious anthropological differences between Hitto-Luwians and the Minoans may be considered as another indirect testimony against this hypothesis.

There are most recent works focused on the Luwian connection, but not in terms of the Minoan language being Anatolian, but rather of possible borrowings from Luwian, including the origin of the writing.[20]

Lycian

In an article from 2001, Professor of Classics (Emerita) at Tel Aviv University, Margalit Finkelberg, demonstrated a "high degree of correspondence between the phonological and morphological system of Minoan and that of Lycian" and proposed that "the language of Linear A is either the direct ancestor of Lycian or a closely related idiom.".[21]

Phoenician

In 2001, the journal Ugarit-Forschungen published the article "The First Inscription in Punic — Vowel Differences in Linear A and B" by Jan Best, claiming to demonstrate how and why Linear A notates an archaic form of Phoenician.[22] This was a continuation of attempts by Cyrus Gordon in finding connections between Minoan and West Semitic languages.

Indo-Iranian

Another recent interpretation, based on the frequencies of the syllabic signs and on complete palaeographic comparative studies, suggests that the Minoan Linear A language belongs to the Indo-Iranian family of Indo-European languages.[23] Studies by Hubert La Marle include a presentation of the morphology of the language, avoid the complete identification of phonetic values between Linear A and B, and also avoid comparing Linear A with Cretan Hieroglyphs.[23] La Marle uses the frequency counts to identify the type of syllables written in Linear A, and takes into account the problem of loanwords in the vocabulary.[23] However, the La Marle interpretation of Linear A has been rejected by John Younger of Kansas University showing that La Marle has invented erroneous and arbitrary new transcriptions based on resemblances with many different script systems at will (as Phoenician, Hieroglyphic Egyptian, Hieroglyphic Hittite, Ethiopian, Cypro-Minoan, etc.), ignoring established evidence and internal analysis, while for some words he proposes religious meanings inventing names of gods and rites.[24] La Marle rebutted in "An answer to John G. Younger's remarks on Linear A" in 2010.[25]

Tyrrhenian

Italian scholar Giulio M. Facchetti attempted to link Linear A to the Tyrrhenian language family comprising Etruscan, Rhaetic, and Lemnian. This family is reasoned to be a pre-Indo-European Mediterranean substratum of the 2nd millennium BCE, sometimes referred to as Pre-Greek. Facchetti proposed some possible similarities between the Etruscan language and ancient Lemnian, and other Aegean languages like Minoan.[26] Michael Ventris who, along with John Chadwick, successfully deciphered Linear B, also believed in a link between Minoan and Etruscan.[27] The same perspective is supported by S. Yatsemirsky in Russia.[28]

Single word decipherment attempts

Some researchers suggest that a few words or word elements may be recognized, without (yet) enabling any conclusion about relationship with other languages. In general, they use analogy with Linear B in order to propose phonetic values of the syllabic sounds. John Younger, in particular, thinks that place names usually appear in certain positions in the texts, and notes that the proposed phonetic values often correspond to known place names as given in Linear B texts (and sometimes to modern Greek names). For example, he proposes that three syllables, read as KE-NI-SO, might be the indigenous form of Knossos.[29] Likewise, in Linear A, MA+RU is suggested to mean wool, and to correspond both to a Linear B pictogram with this meaning, and to the classical Greek word μαλλός with the same meaning (in that case a loan word from Minoan).[3]

Unicode

The Linear A alphabet (U+10600–U+1077F) was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0.

| Linear A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1060x | 𐘀 | 𐘁 | 𐘂 | 𐘃 | 𐘄 | 𐘅 | 𐘆 | 𐘇 | 𐘈 | 𐘉 | 𐘊 | 𐘋 | 𐘌 | 𐘍 | 𐘎 | 𐘏 |

| U+1061x | 𐘐 | 𐘑 | 𐘒 | 𐘓 | 𐘔 | 𐘕 | 𐘖 | 𐘗 | 𐘘 | 𐘙 | 𐘚 | 𐘛 | 𐘜 | 𐘝 | 𐘞 | 𐘟 |

| U+1062x | 𐘠 | 𐘡 | 𐘢 | 𐘣 | 𐘤 | 𐘥 | 𐘦 | 𐘧 | 𐘨 | 𐘩 | 𐘪 | 𐘫 | 𐘬 | 𐘭 | 𐘮 | 𐘯 |

| U+1063x | 𐘰 | 𐘱 | 𐘲 | 𐘳 | 𐘴 | 𐘵 | 𐘶 | 𐘷 | 𐘸 | 𐘹 | 𐘺 | 𐘻 | 𐘼 | 𐘽 | 𐘾 | 𐘿 |

| U+1064x | 𐙀 | 𐙁 | 𐙂 | 𐙃 | 𐙄 | 𐙅 | 𐙆 | 𐙇 | 𐙈 | 𐙉 | 𐙊 | 𐙋 | 𐙌 | 𐙍 | 𐙎 | 𐙏 |

| U+1065x | 𐙐 | 𐙑 | 𐙒 | 𐙓 | 𐙔 | 𐙕 | 𐙖 | 𐙗 | 𐙘 | 𐙙 | 𐙚 | 𐙛 | 𐙜 | 𐙝 | 𐙞 | 𐙟 |

| U+1066x | 𐙠 | 𐙡 | 𐙢 | 𐙣 | 𐙤 | 𐙥 | 𐙦 | 𐙧 | 𐙨 | 𐙩 | 𐙪 | 𐙫 | 𐙬 | 𐙭 | 𐙮 | 𐙯 |

| U+1067x | 𐙰 | 𐙱 | 𐙲 | 𐙳 | 𐙴 | 𐙵 | 𐙶 | 𐙷 | 𐙸 | 𐙹 | 𐙺 | 𐙻 | 𐙼 | 𐙽 | 𐙾 | 𐙿 |

| U+1068x | 𐚀 | 𐚁 | 𐚂 | 𐚃 | 𐚄 | 𐚅 | 𐚆 | 𐚇 | 𐚈 | 𐚉 | 𐚊 | 𐚋 | 𐚌 | 𐚍 | 𐚎 | 𐚏 |

| U+1069x | 𐚐 | 𐚑 | 𐚒 | 𐚓 | 𐚔 | 𐚕 | 𐚖 | 𐚗 | 𐚘 | 𐚙 | 𐚚 | 𐚛 | 𐚜 | 𐚝 | 𐚞 | 𐚟 |

| U+106Ax | 𐚠 | 𐚡 | 𐚢 | 𐚣 | 𐚤 | 𐚥 | 𐚦 | 𐚧 | 𐚨 | 𐚩 | 𐚪 | 𐚫 | 𐚬 | 𐚭 | 𐚮 | 𐚯 |

| U+106Bx | 𐚰 | 𐚱 | 𐚲 | 𐚳 | 𐚴 | 𐚵 | 𐚶 | 𐚷 | 𐚸 | 𐚹 | 𐚺 | 𐚻 | 𐚼 | 𐚽 | 𐚾 | 𐚿 |

| U+106Cx | 𐛀 | 𐛁 | 𐛂 | 𐛃 | 𐛄 | 𐛅 | 𐛆 | 𐛇 | 𐛈 | 𐛉 | 𐛊 | 𐛋 | 𐛌 | 𐛍 | 𐛎 | 𐛏 |

| U+106Dx | 𐛐 | 𐛑 | 𐛒 | 𐛓 | 𐛔 | 𐛕 | 𐛖 | 𐛗 | 𐛘 | 𐛙 | 𐛚 | 𐛛 | 𐛜 | 𐛝 | 𐛞 | 𐛟 |

| U+106Ex | 𐛠 | 𐛡 | 𐛢 | 𐛣 | 𐛤 | 𐛥 | 𐛦 | 𐛧 | 𐛨 | 𐛩 | 𐛪 | 𐛫 | 𐛬 | 𐛭 | 𐛮 | 𐛯 |

| U+106Fx | 𐛰 | 𐛱 | 𐛲 | 𐛳 | 𐛴 | 𐛵 | 𐛶 | 𐛷 | 𐛸 | 𐛹 | 𐛺 | 𐛻 | 𐛼 | 𐛽 | 𐛾 | 𐛿 |

| U+1070x | 𐜀 | 𐜁 | 𐜂 | 𐜃 | 𐜄 | 𐜅 | 𐜆 | 𐜇 | 𐜈 | 𐜉 | 𐜊 | 𐜋 | 𐜌 | 𐜍 | 𐜎 | 𐜏 |

| U+1071x | 𐜐 | 𐜑 | 𐜒 | 𐜓 | 𐜔 | 𐜕 | 𐜖 | 𐜗 | 𐜘 | 𐜙 | 𐜚 | 𐜛 | 𐜜 | 𐜝 | 𐜞 | 𐜟 |

| U+1072x | 𐜠 | 𐜡 | 𐜢 | 𐜣 | 𐜤 | 𐜥 | 𐜦 | 𐜧 | 𐜨 | 𐜩 | 𐜪 | 𐜫 | 𐜬 | 𐜭 | 𐜮 | 𐜯 |

| U+1073x | 𐜰 | 𐜱 | 𐜲 | 𐜳 | 𐜴 | 𐜵 | 𐜶 | |||||||||

| U+1074x | 𐝀 | 𐝁 | 𐝂 | 𐝃 | 𐝄 | 𐝅 | 𐝆 | 𐝇 | 𐝈 | 𐝉 | 𐝊 | 𐝋 | 𐝌 | 𐝍 | 𐝎 | 𐝏 |

| U+1075x | 𐝐 | 𐝑 | 𐝒 | 𐝓 | 𐝔 | 𐝕 | ||||||||||

| U+1076x | 𐝠 | 𐝡 | 𐝢 | 𐝣 | 𐝤 | 𐝥 | 𐝦 | 𐝧 | ||||||||

| U+1077x | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ Beginning date refers to first attestations, the assumed origins of all scripts lie further back in the past.

References

Citations

- ↑ Haarmann 2008, pp. 12–46.

- ↑ Palaima 1997, pp. 121–188.

- 1 2 Younger, John (2000). "Linear A Texts in Phonetic Transcription: 7b. The Script". University of Kansas.

- ↑ Packard 1974, Chapter 1: Introduction.

- ↑ Owens 1999, pp. 23–24 (David Packard, in 1974, calculated a sound-value difference of 10.80% ± 1.80%; Yves Duhoux, in 1989, calculated a sound-value difference of 14.34% ± 1.80% and Gareth Owens, in 1996, calculated a sound-value difference of 9–13%).

- ↑ Younger, John (2000). "Linear A Texts in Phonetic Transcription: 5. Basic Statistics". University of Kansas. Younger: "if there are 4002 characters (font Times, pitch 12, no spaces) on an 8 1/2 x 11 inch sheet of paper with 1 inch margins, all extant Linear A would take up 1.84 pages." (14.34 pages for Linear B).

- ↑ Schoep 1999, pp. 201–221.

- 1 2 Finkelberg 1998, pp. 265–272.

- ↑ Book review by Daniel J. Pullen (Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2009) of W. D. Taylour, R. Janko, Ayios Stephanos: Excavations at a Bronze Age and Medieval Settlement in Southern Laconia. British School at Athens, 2008. "Its location on the Laconian coast, easily accessible from Kythera, undoubtedly encouraged early contacts with Crete whether directly or indirectly (see the Linear A sign catalogued in chapter 11)."

- ↑ Olivier 1986, pp. 377f.

- ↑ Robinson 2009, p. 54.

- ↑ Younger, John (2000). "Linear A Texts in Phonetic Transcription". University of Kansas. See "1. List of Linked Files" for a comprehensive list of known texts written in Linear A.

- 1 2 Nagy 1963, p. 210 (Footnote #24).

- ↑ Georgiev 1963, pp. 1–104.

- ↑ Nagy 1963, pp. 181–211.

- ↑ Owens 2007, pp. 3–4: "Η έρευνα απέδειξε ότι η μινωική γλώσσα σχετίζεται με την ελληνική περισσότερο από κάθε άλλη ινδοευρωπαϊκή γλώσσα, χωρίς να αποτελεί μια άλλη ελληνική διάλεκτο αλλά ένα χωριστό παρακλάδι της ινδοευρωπαϊκής οικογένειας...υπάρχουν λέξεις που εντοπίζονται και στην ελληνική γλώσσα αλλά και σε άλλες, όπως τη σανσκριτική και τη χεττιτική, τη λατινική, της ίδιας οικογένειας.".

- ↑ Owens 1999, pp. 15–56.

- ↑ "The Language of the Minoans". Crete Gazette. 2006.

- ↑ Palmer 1958, pp. 75–100.

- ↑ Marangozis, John (2006). An introduction to Minoan Linear A. LINCOM Europa.

- ↑ Finkelberg, Margalit, "The Language of Linear A: Greek, Semitic, or Anatolian?ar A: Greek, Semitic, or Anatolian?", in: Drews, Robert (ed.), Greater Anatolia dnt eh Ind-Hittite Language Family, Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph 38, Washington, DC, 2001.

- ↑ Dietrich & Loretz 2001.

- 1 2 3 La Marle, Hubert. Linéaire A, la première écriture syllabique de Crète. Paris: Geuthner, 4 Volumes, 1997–1999, 2006; Introduction au linéaire A. Geuthner, Paris, 2002; L'aventure de l'alphabet: les écritures cursives et linéaires du Proche-Orient et de l'Europe du sud-est à l'Âge du Bronze. Paris: Geuthner, 2002; Les racines du crétois ancien et leur morphologie: communication à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 2007.

- ↑ Younger, John (2009). "Linear A: Critique of Decipherments by Hubert La Marle and Kjell Aartun". University of Kansas. According to Younger, La Marle "assigns phonetic values to Linear signs based on superficial resemblances to signs in other scripts (the choice of scripts being already prejudiced to include only those from the eastern Mediterranean and northeast Africa), as if 'C looks like O so it must be O.'"

- ↑ La Marle, Hubert (September 2010). "An answer to John G. Younger's remarks on Linear A". Academia.edu.

- ↑ Facchetti & Negri 2003.

- ↑ Yatsemirsky 2011.

- ↑ Younger, John (2000). "Linear A Texts in Phonetic Transcription: 10c. Place Names". University of Kansas.

Sources

- Chadwick, John (1967). The Decipherment of Linear B. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39830-4.

- Dietrich, Manfried; Loretz, Oswald (2001). In Memoriam: Cyrus H. Gordon. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 3-934628-00-1.

- Facchetti, Giulio M.; Negri, Mario (2003). Creta Minoica: Sulle tracce delle più antiche scritture d'Europa (in Italian). Firenze: L.S. Olschki. ISBN 88-222-5291-8.

- Finkelberg, Margalit (1998). "Bronze Age Writing: Contacts between East and West". In E. H. Cline and D. Harris-Cline. The Aegean and the Orient in the Second Millennium. Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Symposium, Cincinnati, 18–20 April 1997. Liège 1998 (PDF). Aegeum. 18. pp. 265–272.

- Georgiev, Vladimir I. (1963). "Les deux langues des inscriptions crétoises en linéaire A". Linguistique Balkanique (in French). 7 (1): 1–104.

- Haarmann, Harald (2008). "The Danube Script and Other Ancient Writing Systems: A Typology of Distinctive Features". The Journal of Archaeomythology. 4 (1): 12–46.

- Nagy, Gregory (1963). "Greek-Like Elements in Linear A". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. Harvard University Press (4): 181–211.

- Olivier, J. P. (1986). "Cretan Writing in the Second Millennium B.C.". World Archaeology. 17 (3): 377–389. doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979977.

- Owens, Gareth (1999). "The Structure of the Minoan Language" (PDF). Journal of Indo-European Studies. 27 (1–2): 15–56.

- Owens, Gareth Alun (2007). "Η Δομή της Μινωικής Γλώσσας ["The Structure of the Minoan Language"]" (PDF) (in Greek). Heraklion: TEI of Crete –Daidalika.

- Packard, David W. (1974). Minoan Linear A. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02580-6.

- Palaima, Thomas G. (1997) [1989]. "Cypro-Minoan Scripts: Problems of Historical Context". In Duhoux, Yves; Palaima, Thomas G.; Bennet, John. Problems in Decipherment. Louvain-La-Neuve: Peeters. pp. 121–188. ISBN 90-6831-177-8.

- Palmer, Leonard Robert (1958). "Luvian and Linear A". Transactions of the Philological Society. 57 (1): 75–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1958.tb01273.x.

- Robinson, Andrew (2009). Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956778-2.

- Schoep, Ilse (1999). "Tablets and Territories? Reconstructing Late Minoan IB Political Geography through Undeciphered Documents". American Journal of Archaeology. 103 (2): 201–21. doi:10.2307/506745. JSTOR 506745 – via JSTOR. (registration required (help)).

- Yatsemirsky, Sergei A. (2011). Opyt sravnitel'nogo opisaniya minoyskogo, etrusskogo i rodstvennyh im yazykov [Tentative Comparative Description of Minoan, Etruscan and Related Languages] (in Russian). Moscow: Yazyki slavyanskoy kul'tury. ISBN 978-5-9551-0479-9.

Further reading

- Best, Jan G. P. (1972). Some Preliminary Remarks on the Decipherment of Linear A. Amsterdam: Hakkert.

- Marangozis, John (2006). An introduction to Minoan Linear A. LINCOM Europa.

- Montecchi, Barbara (January 2010). "A Classification Proposal of Linear A Tablets from Haghia Triada in Classes and Series". Kadmos. 49 (1): 11–38. doi:10.1515/KADMOS.2010.002.

- Nagy, Gregory (October 1965). "Observations on the Sign-Grouping and Vocabulary of Linear A". American Journal of Archaeology. 69 (4): 295–330. doi:10.2307/502181.

- Palmer, Ruth (1995). "Linear A Commodities: A Comparison of Resources" (PDF). Aegeum. 12.

- Thomas, Helena. Understanding the transition from Linear A to Linear B script. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Supervisor: Professor John Bennet. Thesis (D. Phil.). University of Oxford, 2003. Includes bibliographical references (leaves 311-338).

- Woodard, Roger D. (1997). Greek Writing from Knossos to Homer. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510520-6. (Review)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Linear A. |

- Linear A Texts in Phonetic Transcription by John Younger (Last Update: 20 February 2010).

- Linear A Research by Hubert La Marle

- DAIDALIKA - Scripts and Languages of Minoan and Mycenaean Crete

- Omniglot: Writing Systems & Languages of the World

- Mnamon: Antiche Scritture del Mediterraneo (Antique Writings of the Mediterranean)

- GORILA Volume 1

- Interpretation of the Linear A Scripts by Gia Kvashilava

- Aum Sign in Crete

- Ugarit-Forschungen, Band 32