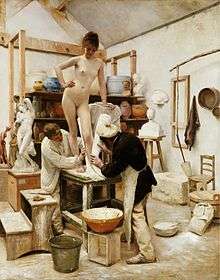

Lifecasting

Lifecasting is the process of creating a three-dimensional copy of a living human body, through the use of molding and casting techniques.[1] In rare cases lifecasting is also practiced on living animals. The most common lifecasts are of torsoes, pregnant bellies, hands, faces, and gentalia and it is possible for an experienced lifecasting practitioner to copy any part of the body. Lifecasting is usually limited to a section of the body at a time, but full-body lifecasts are achievable too. Compared with other three-dimensional representations of humans, the standout feature of lifecasts is their high level of realism and detail. Lifecasts can replicate details as small as fingerprints and pores.

Process

There are a variety of lifecasting techniques which differ to some degree; the following steps illustrate a general and simplified outline of the process:

- Model preparation. An oily substance such as petroleum jelly is applied to the skin and/or hair of the model to help prevent the mold adhering to their skin and hair. If the lifecast is to include the face or head, a rubber swimming cap may be worn to prevent the mold from adhering to the head hair.

- Model pose. The model takes the desired stationary pose, and must remain in this pose until the mold is removed from the body. Supports to help the model are carefully designed.

- Mold application. Mold material is applied to the surface of the model's body. The mold material is usually applied as a thick liquid that takes the shape of the body. Body parts may also be dunked into containers of mold media (except plaster).

- Mold curing and reinforcement. The applied mold material cures to a more rigid and solid form. Sometimes more materials are added at this point to further strengthen and support the mold.

- Demold. Once the reinforced mold has attained the necessary strength it is carefully removed from the model's body.

- Mold reassembly and modification. If the mold was created in multiple parts the parts are now sometimes joined back together. The mold itself may be repaired, altered, or added to. Walls may be constructed to help contain the casting material, or further mold reinforcements added.

- Casting. A casting material is painted or poured into the mold, usually in liquid form, though deformable solids can be used as well. Artists commonly incorporate hanging hardware at this stage as well.

- Demold cast. Once the casting material has acquired the shape of the mold and cured fully, the cast is carefully removed from the mold. Molds may survive but often do not, resulting in one-of-a-kind, "one-out" works. Silicone molds will last for many castings.

Molding and casting materials

A variety of materials can be used for both the molding and casting stages of the lifecasting process. For molding, alginate, and plaster bandages are the most popular materials. Less common mold materials are silicones, waxes, gelatins, and plaster. Plaster and gypsum cement are the most commonly used casting materials, but various clays, concretes, plastics and metals are also in common use. Ice, glass, and even chocolate have been used on occasion as casting materials. Work is being done with imaging technology to map the skin's surface which may enable re-creation of the shape without touching the body. Since the weight of material deforms the body, if only slightly, this new technique may enable even more perfect work, but will not give the skin texture the above-listed materials do.

Risks and challenges

Compared to the molding of inanimate objects, lifecasting poses some specific challenges and risks. Since the mold is made directly on the skin of the model, for safety and health reasons the molding materials must be non-toxic. The mold must not heat up too much or else discomfort and even severe burns could occur. The molding process must also be completed within a relatively short time frame, usually a half-hour or less, since people have limited endurance in holding a stationary pose. Methods to allow the model to continue breathing must also be used when a mold covers the mouth and nostrils. (Generally the nostrils are kept clear, but not with straws.) If the model is captured with lungs deflated it will be impossible to take a deep breath. To prevent injury or trapping the model in the mold, the shape and position of the mold must be well planned prior to application.

Even experienced lifecasters can occasionally have trouble with snagging small body hairs, and the mold being somewhat uncomfortable. In rare cases some models can have allergic reactions to molding materials, can faint from holding a stationary pose for too long, or can experience anxiety from being enclosed in the mold.

However, far from always being a negative experience, many models actually find the experience enjoyable. The necessity of an extended stationary pose and the feeling of being enclosed by the warm molding materials leads some to feel extreme relaxation or even enter into meditative states. In relaxed poses some models even fall asleep while being lifecast. The application of the molding materials can also feel like a soft massage. Models often compare the feeling of a face lifecast to the feeling of a facial. Beauty salons sometimes perform lifecasting when they apply plaster mixed with herbs to the face, over cream, with the goal of gently warming the face with the cream and herbs.

Lifecasting and art

Lifecasting is considered a sculptural art by some, while others think it is more a technical skill and the work of artisans. Critics of lifecasting as an art claim that it lacks the talent or creativity that more conventional sculptural disciplines require. This criticism echoes that heard in artistic circles during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries relating to photography. In fact lifecasting has been called a three-dimensional type of photography. As with photographs, lifecasts are sometimes manipulated, altered and incorporated with other media. Lifecasters are united only by the fact that each work starts with a lifecast. Artistic choices begin with choice of model, of pose, and of area of the body shown. Defining the edge is clearly a sculptural act. Probably the most popular alteration is to add paint and various finishes to the surface of the lifecast. Duane Hanson is the best-known contemporary sculptor to use lifecasting in his works. He perfectly reproduced the entire body including hair and skintone. His "everyman" works were dressed and posed to look like unexceptional people.

Applications

Lifecasting allows creation of exact portraits and body reproduction, works which may have artistic and personal value. Lifecasting is regularly practiced in the special effects industry, where it is used in the creation of prosthetics, props, and animatronics, most commonly for film and television. Lifecasting also finds medical use in the creation and fitting of prostheses and dentures.

Lifecasting has also found a niche market in the creation of personalized dildos, which are the cast replicas of erect penises. Several companies sell lifecasting kits designed specifically for this purpose. It is also possible to make molds of the vagina as well, though the process is more complicated.

Pregnant women often choose to have a belly cast of their torso made between the 35th - 38th week of pregnancy to capture their shape.

A death mask is a similar process to lifecasting, with the major difference being that a deathmask is created on a dead person's face. These were common in earlier times; obviously there is no concern with breathing or discomfort.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lifecasting. |