Liam Lynch (Irish republican)

| Liam Lynch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

9 November 1893 Barnagurraha, County Limerick, Ireland, |

| Died |

10 April 1923 (aged 29) Clonmel, County Tipperary, Ireland |

| Allegiance | Irish Republican Army |

| Years of service | 1917–23 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held |

Officer Commanding, 2nd Cork Brigade, Irish Republican Army, 1919 – April 1921 Commander, First Southern Division, Irish Republican Army, April 1921 – March 1922 Chief of Staff, Irish Republican Army, March 1922 – April 1923 |

| Battles/wars |

Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War |

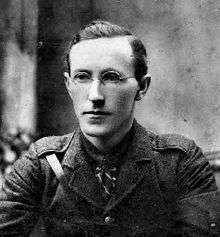

Liam Lynch (Irish: Liam Ó Loingsigh; 9 November 1893 – 10 April 1923) was an officer in the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and the commanding general of the Irish Republican Army during the Irish Civil War.

Early life

Lynch was born in the townland of Barnagurraha, Limerick, near Mitchelstown, Cork, to Jeremiah and Mary Kelly Lynch. During his first 12 years of schooling he attended Anglesboro School.

In 1910, at the age of 17, he started an apprenticeship in O'Neill's hardware trade in Mitchelstown, where he joined the Gaelic League and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Later he worked at Barry's Timber Merchants in Fermoy. In the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising, he witnessed the shooting and arrest of David and Richard Kent of Bawnard House by the Royal Irish Constabulary. Due to the Kent incident Liam Lynch decided to dedicate his life to the Irish Republic and freedom.[1] In 1917 Lynch was elected First Lieutenant of the Irish Volunteer Company. The Irish Volunteer Company resided in Fermoy.[2]

War of Independence

In Cork, Lynch re-organised the Irish Volunteers – the paramilitary organisation that became the Irish Republican Army – in 1919, becoming commandant of the Cork No. 2 Brigade of the IRA during the guerrilla Anglo-Irish War. Lynch helped capture a senior British officer, General Cuthbert Lucas, in June 1920, shooting a Colonel Danford in the incident. Lucas later escaped while being held by IRA men in County Clare. Lynch was captured, together with the other officers of the Cork No. 2 Brigade, in a British raid on Cork City Hall in August 1920. Terence McSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork, was among those captured – he later died on hunger strike in protest at his detention. Lynch, however, gave a false name and was released three days later. In the meantime, the British had assassinated two other innocent men named Lynch, whom they had confused with him. Having "made himself a leader out of force of his own convictions...possessed by a sense of mission and by revolutionary ardour",[3] Lynch believed independence could only be "hewed" by the army.

In September 1920, Lynch, along with Ernie O'Malley, commanded a force that took the British Army barracks at Mallow. The arms in the barracks were seized and the building partially burnt. Before the end of 1920, Lynch's brigade had successfully ambushed British troops on two other occasions. Lynch's guerrilla campaign continued into early 1921, with some successes such as the ambush and killing of 13 British soldiers near Millstreet.

In April 1921, the Irish Republican Army was re-organised into divisions based on regions. Lynch's reputation was such that he was made commander of the 1st Southern Division. From April 1921 until the Truce that ended the war in July 1921, Lynch's command was put under increasing pressure by the deployment of more British troops into the area and the British use of small mobile units to counter IRA guerrilla tactics. Lynch was no longer in command of the Cork No. 2 Brigade as he had to travel in secret to each of the nine IRA Brigades in Munster. By the time of the Truce, the IRA under Liam Lynch were increasingly hard pressed and short of arms and ammunition. Lynch therefore welcomed the Truce as a respite; however, he expected the war to continue after it ended.

The Treaty

The war formally ended with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty between the Irish negotiating team and the British government in December 1921.

Lynch was opposed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, on the grounds that it disestablished the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1916 in favour of Dominion status for Ireland within the British Empire. He became Chief of Staff in March 1922 of the IRA, much of which was also against the Treaty. Lynch, however, did not want a split in the republican movement and hoped to reach a compromise with those who supported the Treaty ("Free Staters") by the publication of a republican constitution for the new Irish Free State. But the British would not accept this, as the Treaty had only just been signed and ratified, leading to a bitter split in Irish ranks and ultimately civil war.

Civil War

Although Lynch opposed the seizure of the Four Courts in Dublin by a group of hardline republicans, he joined its garrison in June 1922 when it was attacked by the newly formed National Army. This marked the beginning of the Irish Civil War. Lynch was arrested by the Free State forces but was allowed to leave Dublin, on the understanding that he would try and halt the fighting. Instead, he quickly began organising resistance elsewhere.

With the capture of Joe McKelvey at the Four Courts, Liam Lynch resumed the position of Chief-of-Staff of the Anti-Treaty Irish Republican Army forces (also called the "Irregulars"), which McKelvey had temporarily taken over. Lynch, who was most familiar with the south, planned to establish a 'Munster Republic' which he believed would frustrate the creation of the Free State. The 'Munster Republic' would be defended by the 'Limerick-Waterford Line'. This consisted of, moving from east to west, the city of Waterford, the towns of Carrick-on-Suir, Clonmel, Fethard, Cashel, Golden, and Tipperary, ending in the city of Limerick, where Lynch established his headquarters. In July, he led its defence but it fell to Free State troops on 20 July 1922.

Lynch retreated further south and set up his new headquarters at Fermoy. The 'Munster Republic' fell in August 1922, when Free State troops landed by sea in Cork and Kerry. Cork City was taken on 8 August and Lynch abandoned Fermoy the next day. The Anti-Treaty forces then dispersed and pursued guerrilla tactics. In the process of this assault, his opponent Michael Collins was killed in Cork on 22 August.

Lynch contributed to the growing bitterness of the war by issuing what were known as the "orders of frightfulness" against the Provisional government on 30 November 1922. This General Order sanctioned the killing of Free State TDs (members of Parliament) and Senators, as well as certain judges and newspaper editors in reprisal for the Free State's killing of captured republicans. The first republican prisoners to be executed were four IRA men captured with arms on 14 November 1922, followed by the execution of republican leader Erskine Childers on 17 November. Lynch then issued his orders, which were acted upon by IRA men, who killed TD Sean Hales and wounded another TD outside the Dáil. In reprisal, the Free State immediately shot four republican leaders, Rory O'Connor, Liam Mellows, Dick Barrett and Joe McKelvey. This led to a cycle of atrocities on both sides, including the Free State official execution of 77 republican prisoners and "unofficial" killing of roughly 150 other captured republicans. Lynch's men for their part launched a concerted campaign against the homes of Free State members of parliament. Among the acts they carried out were the burning of the house of TD Seán McGarry, resulting in the death of his seven-year-old son, and the murder of Free state minister Kevin O'Higgins' elderly father and burning of his family home at Stradbally in early 1923.

Lynch was heavily criticised by some republicans, notably Ernie O'Malley, for his failure to co-ordinate their war effort and for letting the conflict peter out into inconclusive guerrilla warfare. Lynch made unsuccessful efforts to import mountain artillery from Germany to turn the tide of the war. In March 1923, the Anti-Treaty IRA Army Executive met in a remote location in the Nire Valley. Several members of the executive proposed ending the civil war but Lynch opposed them. Lynch narrowly carried a vote to continue the war.

Death

On 10 April 1923 an Irish Army unit was seen approaching Lynch's secret headquarters in the Knockmealdown Mountains. Liam was carrying important papers that he knew must not fall into enemy hands, so he and his six comrades began a strategic retreat.

To their shock, they ran into another unit of 50 soldiers approaching from the opposite side. Lynch was hit by rifle fire from the road at the foot of the hill. Knowing the value of the papers they carried, he ordered his men to leave him behind.[4] When the soldiers finally reached Lynch, they initially believed him to be Éamon de Valera but he informed them – "I am Liam Lynch, Chief-of-Staff of the Irish Republican Army. Get me a priest and doctor, I'm dying."[5][6] He was carried on an improvised stretcher manufactured from guns to "Nugents" pub in Newcastle, at the foot of the mountains. He was later brought to the hospital in Clonmel and died that evening at 8 p.m.

Liam Lynch was laid to rest two days later at Kilcrumper Cemetery, near Fermoy, County Cork.

Legacy

According to historian Tom Mahon, the Irish Civil War was "effectively ended" by the shot that killed Liam Lynch. Twenty days later, Lynch's successor, Frank Aiken, gave the order to "Surrender and dump arms."[7]

On 7 April 1935, 12 years later, the anti-Treaty Government of Éamon de Valera erected a 60-foot-high (18 m) round tower monument on the spot where Lynch was thought to have fallen, on Knockmealdown Mountain.

The Irish Defence Forces barracks at Kilworth, County Cork, is named Camp Ó Liongsigh after Liam Lynch. Furthermore, the bloodstained tunic that was worn by Lynch on the day he was shot is on permanent display at the National Museum at Collins Barracks in Dublin.

The Good Friday Agreement, which ended The Troubles in Northern Ireland, was signed on the 75th anniversary of Liam Lynch's death.

References

- ↑ National Graves Association, "Liam Lynch- Life"

- ↑ RSF, "Liam Lynch RSFCork

- ↑ Hart. P, "IRA and its enemies: Violence and Community in Cork, 1916-1923 ", (Oxford 1998), p.205

- ↑ The Wild Geese "Liam Lynch: Victim of the Irish Civil War", 2001

- ↑ Ryan, Meda (1986). Liam Lynch: the real chief. Mercier Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-85342-764-3. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ O'Donoghue, Florence (1954). No other law: the story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916–1923. Irish Press. p. 305. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ Tom Mahon & James J. Gillogly, Decoding the IRA, Mercier Press, 2008. Page 66.

Sources

- Hopkinson, M Green against Green, the Irish Civil War (Dublin 1988)

- Walsh, P.V The Irish Civil War 1922–23 – A Study of the Conventional Phase

- Ryan, Meda, The Real Chief: The Story of Liam Lynch (Cork 1986)

- O'Donoghue, Florence, No Other Law- The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916–1923 (Dublin 1954, 1986)

- O'Farrell, P Who's Who in the Irish War of Independence & Civil

- Borgonovo, J, The Battle for Cork July–August 1922

External links

- Letters of Liam Lynch

- Liam Lynch Dead

- The Irish War

- Liam Lynch (Liam ui Loinsigh)

- Irish Republican Brotherhood

- Liam Lynch: Victim of the Irish Civil War