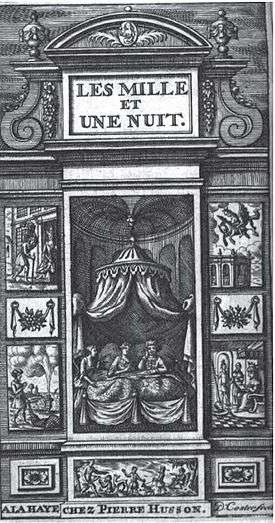

Les mille et une nuits

- For the French publisher's imprint, see Fayard.

Les mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français ("The Thousand and One Nights, Arab stories translated into French"), published in 12 volumes between 1704 and 1717, was the first European version of The Thousand and One Nights tales. The French translation by Antoine Galland (1646-1715) derived from an Arabic text of the Syrian recension of the medieval work[1] as well as other sources. It included stories that are not found in the original Arabic manuscripts — the so-called "orphan tales" — such as the famous "Aladdin" and "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves", which first appeared in print in Galland's form. Immensely popular at the time of initial publication, and enormously influential later, subsequent volumes were introduced using Galland's name although the stories were written by unknown persons at the behest of a publisher wanting to capitalize on their popularity.

History

Galland had come across a manuscript of "The Tale of Sindbad the Sailor" in Constantinople during the 1690s and in 1701 he published his French translation of it.[2] Its success encouraged him to embark on a translation of a 14th-century Syrian manuscript of tales from The Thousand and One Nights. The first two volumes of this work, under the title Les mille et une nuits, appeared in 1704. The twelfth and final volume was published posthumously in 1717.

Galland translated the first part of his work solely from the Syrian manuscript, but in 1709 he was introduced to another source in the form of a Syrian Christian — a Maronite scholar and monk from Aleppo whom he called Youhenna (“Hanna”) Diab. Galland's diary (March 25, 1709) records that he met Hanna through Paul Lucas, a French traveler who had brought him to Paris. Hanna recounted 14 stories to Galland from memory and Galland chose to include seven of them in his books. (For example, Galland's diary tells that his translation of "Aladdin" was made in the winter of 1709–10. It was included in his volumes IX and X, published in 1710.) This mysterious situation has led some scholars to conclude that Galland invented the "orphan tales" himself and that subsequent Arabic versions are merely later renderings of his original French.

Galland adapted his translation to the taste of the times. The immediate success the tales enjoyed was partly due to the vogue for fairy stories — in French, contes de fées[3] — which had been started in France in the 1690s by Galland's friend Charles Perrault. Galland was also eager to conform to the literary canons of the era. He cut many of the erotic passages out along with all of the poetry. This caused Sir Richard Burton to refer to "Galland's delightful abbreviation and adaptation" which "in no wise represent[s] the eastern original."[4]

Galland’s translation was greeted with immense enthusiasm and was soon further translated into many other European languages:

- English (a "Grub Street" version of 1706 under the title Arabian Nights Entertainments)

- German (1712)

- Italian (1722)

- Dutch (1732)

- Russian (1763)

- Polish (1768)

These produced a wave of imitations and the widespread 18th century fashion for oriental tales.[5]

Contents

Volume 1

Les Mille et une Nuits

- "L'Ane, le Boeuf et le Laboureur" ("The Fable of the Ass, the Ox, and the Labourer")

- "Fable de Chien et du Boeuf" ("The Fable of the Dog and the Ox")

- "Le Marchand et le Génie" ("The Merchant and the Genie")

- "Histoire du premier Vieillard et de la Biche" ("The History of the first Old Man and the Doe")

- "Histoire du second Vieillard et des deux Chiens noirs" ("The Story of the second Old Man and the two black Dogs")

- "Histoire du Pècheur" ("The Story of the Fisherman")

- "Histoire du Roi grec et du Medecin Douban" ("The Story of the Grecian King and the Physician Douban")

- "Histoire du Mari et du Perroquet" ("The Story of the Husband and the Parrot")

- "Histoire du Vizir puni" ("The Story of the Visier that was punished")

- "Histoire du jeune Roi des iles Noires" ("The History of the young King of the Black Isles")

- "Histoire de trois Calenders, fils de Roi, et de cinq dames de Bagdad" ("The Story of the three Calenders, Sons of Kings, and of the Five Ladies of Bagdad")

Volume 2

- "Histoire du premier Calender, fils de Roi" ("The History of the First Calender, a King's Son")

- "Histoire du second Calender, fils de Roi" ("The Story of the Second Calender, a King's Son")

- "Histoire de l'Envieux et de l'Envie" ("The Story of the envious Man, and of him that he envied")

- "Histoire du troisième Calender, fils de Roi" ("The History of the Third Calender, a King's Son")

- "Histoire de Zobéide" ("The Story of Zobeide")

- "Histoire d'Amine" ("The Story of Amine")

Volume 3

- "Histoire de Sindbad le Marin" ("The Story of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Premier voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("His First Voyage")

- "Deuxieme voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("The Second Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Troisième voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("The Third Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Quatrième voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("The Fourth Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Cinquième voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("The Fifth Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Sixième voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("The Sixth Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Septième et dernier voyage de Sindbad le marin" ("The Seventh and last Voyage of Sindbad the Sailor")

- "Les Trois Pommes" ("The Story of the Three Apples")

- "Histoire de la dame massacree et du jeune homme son mari" ("The Story of the Lady that was murdered, and of the young Man her Husband")

- "Histoire de Noureddin Ali, et de Bedreddin Hassan" ("The Story of Noureddin Ali and Bedreddin Hassan")

Volume 4

- "Suite de l'Histoire de Noureddin Ali, et de Bedreddin Hassan" ("End of the story of Noureddin Ali and Bedreddin Hassan")

- "Histoire du petit Bossu" ("The Story of the Little Hunch-back")

- "Histoire que raconta le Marchand chretien" ("The Story told by the Christian Merchant")

- "Histoire racontée par le pourvoyeur du sultan de Casgar" ("The Story told by the Sultan of Casgar's Purveyor")

- "Histoire racontée par le médecin juif" ("The Story told by the Jewish Physician")

- "Histoire que raconta le Tailleur" ("The Story told by the Taylor")

Volume 5

- "Suite de l'Histoire que raconta le Tailleur" ("End of the Story told by the Tailor")

- "Histoire du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber")

- "Histoire du premier Frere du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber's Eldest Brother")

- "Histoire du second Frere du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barrber's Second Brother")

- "Histoire du troisieme Frere du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber's Third Brother")

- "Histoire du quatrieme Frere du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber's Fourth Brother")

- "Histoire du cinquieme Frere du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber's Fifth Brother")

- "Histoire du sixieme Frere du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber's Sixth Brother")

- "Histoire du Barbier" ("The Story of the Barber")

- "Suite de l'Histoire que raconta le Tailleur" ("End of the Story told by the Tailor")

- "Histoire d'Aboulhassan Ali Ebn Becar et de Schemselnihar, favorite du calife Haroun-al-Raschid" ("The History of Aboulhassan Ali Ebn Becar and Schemselnihar, Favourite of Caliph Haroun Alraschid")

Volume 6

- "Histoire des amours de Camaralzaman Prince de l'Isle des enfant de Khalendan, et de Badoure Princesse de la Chine" ("The Story of the Amours of Camaralzaman, Prince of the Isles of the Children of Khaleden, and of Badoura, Princess of China")

- "Suite de l'Histoire de Camaralzaman"

- "Suite de l'histoire de la Princesse de la Chine"

- "Histoire de Marzavan avec la suite de celle de Camaralzaman"

- "Séparation du Prince Camaralzaman d'avec la Princesse Badoure"

- "Histoire de la Princesse Badoure apres la separation du Prince Camaralzaman"

- "Suite de l'histoire du Prince Camaralzaman, depuis sa separation d'avec la Princesse Badoure"

- "Histoire des Princes Amgiad et Assad" ("The Story of the two Princes Amgrad and Assad")

- "Le Prince Assad arrete en entrant dans la ville des Mages"

- "Histoire du Prince Amgiad & d'une dame de la ville des Mages" ("The Story of Prince Amgrad and a Lady of the City of the Magicians")

- "Suite de l'Histoire du Prince Assad"

Volume 7

- "Histoire de Noureddin et de la belle Persienne" ("The Story of Noureddin and the Fair Persian")

- "Histoire de Beder, prince de Perse, et de Giauhare, princesse du royaume du Samandal" ("The Story of Beder, Prince of Persia, and Giahaurre, Princess of Samandal")

Volume 8

- "Histoire de Ganem, Fils d'Abou Ayoub, surmomme l'Esclave d'Amour" ("The History of Ganem, Son to Abou Ayoub, and known by the Surname of Love's Slave")

- "Histoire du prince Zein Alasnam et du roi des Génies" ("The History of Prince Zeyn Alasnam, and the King of the Genii")

- "Histoire de Codadad et de ses frères" ("The History of Codadad and his Brothers")

- "Histoire de la princesse Deryabar" ("The History of the Princess of Deryabar")

Volume 9

- "Histoire du dormeur éveillé" ("The Story of the Sleeper Awakened")

- "Histoire d'Aladdin ou la Lampe merveilleuse" ("The Story of Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp")

Volume 10

- "Suite de l'Histoire d'Aladdin ou la Lampe merveilleuse" ("End of the Tale of Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp")

- "Les avantures de Calife Haroun Alraschid"

- "Histoire de l'Aveugle Baba-Alidalla"

- "Histoire de Sidi Nouman"

- "Histoire de Cogia Hassan Alhababbal"

Volume 11

- "Suite de l'Histoire de Cogia Hassan Alhababbal"

- "Histoire d'Ali-Baba et de quarante voleurs exterminés par une esclave" ("Tale of Ali Baba and Forty Thieves Exterminated by a Slave")

- "Histoire d'Ali Cogia, Marchand de Bagdad"

- "Histoire du Cheval enchanté"

Volume 12

- "Histoire du prince Ahmed et de la fee Pari-Banou"

- "Histoire des deux Soeurs jalouses de leur cadette"

Influence

In a 1936 essay, Jorge Luis Borges wrote:

Another fact is undeniable. The most famous and eloquent encomiums of The Thousand and One Nights — by Coleridge, Thomas de Quincey, Stendhal, Tennyson, Edgar Allan Poe, Newman — are from readers of Galland's translation. Two hundred years and ten better translations have passed, but the man in Europe or the Americas who thinks of the Thousand and One Nights thinks, invariably, of this first translation. The Spanish adjective milyunanochesco [thousand-and-one-nights-esque] ... has nothing to do with the erudite obscenities of Burton or Mardrus, and everything to do with Antoine Galland's bijoux and sorceries.[6]

Editions

First publication

- 1704–1717: Les mille et une nuit, contes arabes traduits en François, par M. Galland, Paris: la Veuve Claude Barbin, In-12. 12 vols.

- Vols. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 = 1704–1705, Paris: la Veuve Claude Barbin

- Vol. 7 = 1706, Paris: la Veuve Claude Barbin

- Vol. 8 = 1709, Paris: la Boutique de Claude Barbin, chez la veuve Ricoeur

- Vols. 9, 10 = 1712, Paris: Florentin Delaulne

- Vols. 11, 12 = 1717, Lyon: Briasson

Subsequent editions

- The longest volume in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade series is Les Mille et Une Nuits I, II et III, at 3,504 pages.

- Les mille et une nuits as translated by Galland (Garnier Flammarrion edition, 1965)

See also

References

- ↑ Bibliothèque nationale manuscript "Supplement Arab. No. 2523"

- ↑ Robert L. Mack, ed. (2009). "Introduction". Arabian Nights' Entertainments. Oxford: Oxford UP. pp. ix–xxiii.

- ↑ Muhawi, Ibrahim (2005). "The "Arabian Nights" and the Question of Authorship". Journal of Arabic Literature. 36 (3): 323–337. doi:10.1163/157006405774909899.

- ↑ Burton, The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, v1, Translator's Foreword pp. x

- ↑ This section: Robert Irwin, The Arabian Nights: A Companion (Penguin, 1995), Chapter 1; some details from Garnier-Flammarion introduction

- ↑ Borges, Jorge Luis, "The Translators of The Thousand and One Nights" in The Total Library: Non-Fiction 1922-1986, ed. Eliot Weinberger (Penguin, 1999), pp. 92-93

External links

| French Wikisource has original text related to this article: |