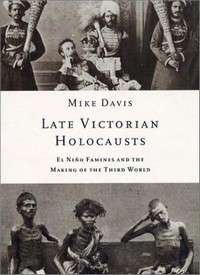

Late Victorian Holocausts

| |

| Author | Mike Davis |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Ecology, Economic History |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Verso |

Publication date | December 2000 |

| Media type | Hardback & Paperback |

| Pages | 464 pp (hardback edition) |

| ISBN | 1-85984-739-0 (Hardback), ISBN 1-85984-382-4 (Paperback) |

| 363.8/09172/4 21 | |

| LC Class | HC79.F3 .D38 2001 |

Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World is a book by Mike Davis about the connection between political economy and global climate patterns, particularly El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). By comparing ENSO episodes in different time periods and across countries, Davis explores the impact of colonialism and the introduction of capitalism, and the relation with famine in particular. Davis argues that "Millions died, not outside the 'modern world system', but in the very process of being forcibly incorporated into its economic and political structures. They died in the golden age of Liberal Capitalism; indeed, many were murdered ... by the theological application of the sacred principles of Smith, Bentham and Mill."[1]

Overview

This book explores the impact of colonialism and the introduction of capitalism during the El Niño-Southern Oscillation related famines of 1876–1878, 1896–1897, and 1899–1902, in India, China, Brazil, Ethiopia, Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines and New Caledonia. It focuses on how colonialism and capitalism in British India and elsewhere increased rural poverty and hunger while economic policies exacerbated famine. The book's main conclusion is that the deaths of 30–60 million people killed in famines all over the world during the later part of the 19th century were caused by laissez faire and Malthusian economic ideology of the colonial governments. In addition to a preface and a short section on definitions, the book is broken into four parts, 'The Great Drought, 1876–1878', 'El Niño and the New Imperialism, 1888–1902', 'Decyphering ENSO', and 'The Political Ecology of Famine'.

"Davis explicitly places his historical reconstruction of these catastrophes in the tradition inaugurated by Rosa Luxemburg in The Accumulation of Capital, where she sought to expose the dependence of the economic mechanisms of capitalist expansion on the infliction of ‘permanent violence’ on the South".[2] Davis argues, for example, that "Between 1875–1900—a period that included the worst famines in Indian history—annual grain exports increased from 3 to 10 million tons", equivalent to the annual nutrition of 25m people. "Indeed, by the turn of the century, India was supplying nearly a fifth of Britain’s wheat consumption at the cost of its own food security."[3] In addition, "Already saddled with a huge public debt that included reimbursing the stockholders of the East India Company and paying the costs of the 1857 revolt, India also had to finance British military supremacy in Asia. In addition to incessant proxy warfare with Russia on the Afghan frontier, the subcontinent’s masses also subsidized such far-flung adventures of the Indian Army as the occupation of Egypt, the invasion of Ethiopia, and the conquest of the Sudan. As a result, military expenditures never comprised less than 25 percent (34 percent including police) of India’s annual budget..."[4] As an example of the effects of both this and of the restructuring of the local economy to suit imperial needs (in Victorian Berar, the acreage of cotton doubled 1875–1900),[5] Davis notes that "During the famine of 1899–1900, when 143,000 Beraris died directly from starvation, the province exported not only thousands of bales of cotton but an incredible 747,000 bushels of grain."[6]

Synopsis

Part 1 : The Great Drought, 1876–1878

Part 1 is further subdivided into three chapters – 1) Victoria's ghosts 2) The Poor Eat Their Homes 3) Gunboats and Messiahs. In this section Davis writes about the drought that occurred in the various parts of the British Empire in the 1870s and the reactions of the colonial government.

Part 2 : El Niño and the New Imperialism, 1888 to 1902

Part 2 is further subdivided into three chapters – 1) The Government of Hell 2) Skeletons at the Feast 3) Millenarian Revolutions. This section deals with the impact of the colonial famine policy and its effects on the colonial subjects.

Part 3 : Decyphering ENSO

Part 3 contains two chapters – 1) The Mystery of the Monsoons and 2) Climates of Hunger. It describes the effect of the ENSO on the lives and livelihood of the people around the world.

Part 4 : The Political Ecology of Famine

The final part of the book has four chapters – 1) The Origins of the Third World 2) India: The Modernization of the Poverty 3) China: Mandates Revoked 4) Brazil: Race and Capital in the Nordeste.

Publication history

This book was first published in Illustrated Hardcover edition in December 2000. It was later issued in paper back format in May 2002.[7] An extract was published in Antipode in 2000.[8]

Reception

This book won the World History Association Book Prize in 2002.[9] It was also featured in the LA Times Best Books of 2001 List.[10]

In his review of the book Economics Nobel prize winner Amartya Sen, while generally approving the historical presentation of the facts, took slight issue with the black-and-white pro-communist conclusions drawn by Davis. In response to Davis' approval of Karl Polanyi's hypothesis that "Indian masses in the second half of the 19th century . . . perished in large numbers because the Indian village community had been demolished", Sen retorts that "this is an enormous exaggeration. In exploding one myth, we have to be careful not to fall for another," however, "it is an illustrative book of the disastrous consequences of fierce economic inequality combined with a drastic imbalance of political voice and power. The late-Victorian tragedies exemplify a wider problem of human insecurity and vulnerability ultimately related to economic disparity and political disempowerment. The relevance of this highly informative book goes well beyond its immediate historical focus."[11]

Reviews

- Sandhu, Sukhdev (20 January 2001). "Hunger strike". The Guardian.

- Bright, Martin (11 February 2001). "From mud to pebbles". The Observer.

- Maxwell, Kenneth (2002). "El Niño in History: Storming Through the Ages/Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño, Famines, and the Making of the Third World (Book)". Foreign Affairs. 81 (3): 169.

- "Mike Davis: Late Victorian Holocausts". Socialist Worker. 24 February 2001.

- Cottrell, Christopher. "Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (review)". Journal of World History. 14 (4): 577–9.

See also

- Great Famine of 1876–78

- Indian famine of 1896–97

- Indian famine of 1899–1900

- Timeline of major famines in India during British rule

- Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–79

- Boxer Rebellion 1899–1900

References

- ↑ Davis, M. (2001). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso. p. 9. ISBN 1-85984-739-0.

- ↑ Callinicos, Alex (2002). "The Actuality of Imperialism". Millennium – Journal of International Studies. 31 (2): 319–326 See p. 321. doi:10.1177/03058298020310020601., :

- ↑ Davis 2000, p. 59

- ↑ Davis 2000, pp. 60–61

- ↑ Davis 2000, p. 65

- ↑ Davis 2000, p. 66

- ↑ Verso Books Publication Page

- ↑ Davis, M. (2000). "The Origin of the Third World". Antipode. 32 (1): 48–89. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00119.

- ↑ The World History Association Book Prize Past Winners

- ↑ Fagan, Brian (2 December 2001). "Late Victorian Holocausts". Nonfiction: The Best Books of 2001. Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Sen, Amartya (18 February 2001). "Apocalypse Then". Books. New York Times.

External links

- "Who's the twerp and who writes twaddle? How rapidly the press marginalises subjects such as the brutality of British colonialism and puts them into a box marked 'loony'" by Peter Wilby in the New Statesman, 26 June 2006.