La Maison Cubiste

_at_the_Salon_d'Automne%2C_1912%2C_detail_of_the_entrance._Photograph_by_Duchamp-Villon.jpg)

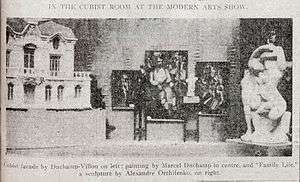

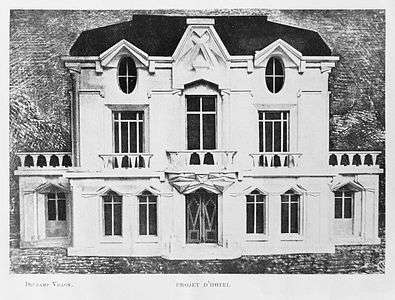

La Maison Cubiste (The Cubist House), also called Projet d'hôtel, was an architectural installation in the Art Décoratif section of the 1912 Paris Salon d'Automne which presented a Cubist vision of architecture and design.[2][3] The facade was designed by the sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon. The interior design of the house was conceived by the painter and designer André Mare, in collaboration with Cubist artists from the Section d'Or group.[4]

Description

%2C_Document_du_Mus%C3%A9e_National_d'Art_Moderne%2C_Paris.jpg)

La Maison Cubiste had a 10 by 8 meter plaster facade with highly geometric trim, behind which were two furnished rooms; a living room (Salon Bourgeois) and a bedroom. Paintings by Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Marie Laurencin, Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger and Roger de La Fresnaye were hung in the salon.[1][5][6] Thousands of spectators at the salon passed through the full-scale model.[7]

It was an early example of art décoratif, a home within which Cubist art could be displayed in the comfort and style of modern, bourgeois life. Cubism now was recognized as significant to a broad range of applications, beyond the bounds of fine art. The movement opened the way toward new possibilities, a modern geometrical vision that could be adapted to architecture, interior design, graphic arts, fashion and industrial design; the basis of Art Deco.[6]

Mare called the living room in which Cubist paintings were hung the Salon Bourgeois. Léger described this name as 'perfect'. In a letter to Mare prior to the exhibition Léger writes: "Your idea is absolutely splendid for us, really splendid. People will see Cubism in its domestic setting, which is very important."[4]

The facade of the house (Façade architecturale), designed by Raymond Duchamp-Villon, was not very radical by modern standards; the lintels and pediments had prismatic shapes, but otherwise the facade resembled an ordinary house of the period. The rooms were furnished in a bourgeois, colorful, and rather traditional manner, particularly compared with the paintings. The critic Emile Sedeyn described Mare's work in the magazine Art et Décoration: "He does not embarrass himself with simplicity, for he multiplies flowers wherever they can be put. The effect he seeks is obviously one of picturesqueness and gaiety. He achieves it."[8] The Cubist element was provided by the paintings. Despite its tameness, the installation was attacked by some critics as extremely radical, which helped make for its success.[9] This architectural installation was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago and Boston.[10][11][12][13][14]

Cubist theory

Metzinger and Gleizes in Du "Cubisme", written during the assemblage of La Maison Cubiste, wrote about the autonomous nature of art, stressing the point that decorative considerations should not govern the spirit of art. Decorative work, to them, was the "antithesis of the picture". "The true picture" wrote Metzinger and Gleizes, "bears its raison d'être within itself. It can be moved from a church to a drawing-room, from a museum to a study. Essentially independent, necessarily complete, it need not immediately satisfy the mind: on the contrary, it should lead it, little by little, towards the fictitious depths in which the coordinative light resides. It does not harmonize with this or that ensemble; it harmonizes with things in general, with the universe: it is an organism..."[17][4]

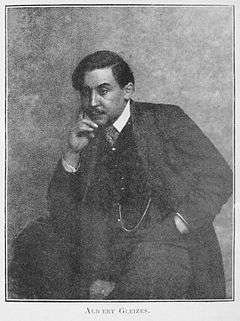

"Mare's ensembles were accepted as frames for Cubist works because they allowed paintings and sculptures their independence", writes Christopher Green, "creating a play of contrasts, hence the involvement not only of Gleizes and Metzinger themselves, but of Marie Laurencin, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed the facade) and Mare's old friends Léger and Roger La Fresnaye".[4] For the occasion, an article entitled Au Salon d'Automne "Les Indépendants" was published in the French newspaper Excelsior, 2 Octobre 1912.[18] Excelsior was the first publication to privilege photographic illustrations in the treatment of news media; shooting photographs and publishing images in order to tell news stories. As such L'Excelsior was a pioneer of photojournalism.

Walter Pach, president of the landmark 1913 exhibition known as the Armory Show, wrote a pamphlet for the occasion, "A Sculptor’s Architecture", in which he discussed Duchamp–Villon’s La Maison Cubiste as exemplary of a new architectural style for the modern era.[16][19] "[T]his work of M. Duchamp-Villon's is an example of what possibilities are contained in a style like the present one whose philosophy is a base", writes Pach, "not a limitation." Continuing, Pach writes, "His work in architecture is by no means a turning aside from his sculpture, but a furthering of it. In the present facade he has simply a "subject" whose organization was to be developed from the forms suggested by a man or woman."[19]

When the art collector Michael Stein, brother of Gertrude Stein, first introduced the work of Duchamp-Villon to Pach, he noted that it would be "admirably suited to the needs of building with concrete". Pach agreed. But speaking with the sculptor convinced Pach that this style had its first application to building with stone, and that it emerged from "an appreciation and solution of the new problem of steel and stone."[19]

The final word I would speak about this architecture is its quality of response to the needs of America. We have yet enormous areas that will be built up into cities, we are going to tear down and rebuild most of the edifices, that already exist. With the freedom that this order gives to individual development and with its possibilities of expansion to make it suit the largest building as well as the smallest, it seems to clearly fix the type of our ideal. Before a photograph of the sky-scrapers of Manhattan Island, Raymond Duchamp-Villon said that he saw the possibilities of the modern cathedral. (Walter Pach, 1913)[19]

Design for the facade of the Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) by Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1912)

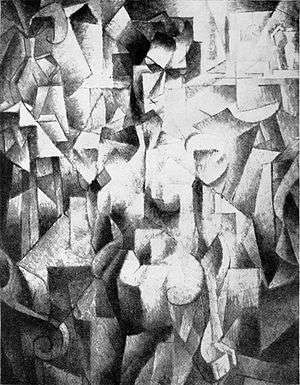

Design for the facade of the Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) by Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1912)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_90.7_x_64.2_cm%2C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Museum.jpg) Jean Metzinger, 1912, Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), oil on canvas, 90.7 x 64.2 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, displayed in the Salon Bourgeois of the installation

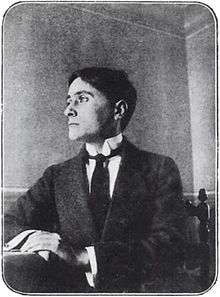

Jean Metzinger, 1912, Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), oil on canvas, 90.7 x 64.2 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, displayed in the Salon Bourgeois of the installation.jpg) Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1912, Projet d'hôtel, La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) detail, Armory Show records, Archives of American Art[12]

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1912, Projet d'hôtel, La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House) detail, Armory Show records, Archives of American Art[12]

Influence

It is difficult to measure the influence of the Maison Cubiste. No actual house following the same design was ever built, and later Deco and modernist residences followed very different models. However, the house was a great success in emphasizing the role of Cubism as an alternative to traditional art and design. Mare joined ranks with furniture designer Louis Süe to form the design company Atelier Français, which became one of he most important furniture manufacturers in Paris, helping to develop the early Art Deco furniture style. The scandal in the press caused by the paintings displayed there was a major contributor to the popularity of Cubist art. Thanks largely to the popularity of the exposition, the term "Cubist" began to be applied to anything modern, from women's haircuts to clothing to theater performances.[9]

Le Corbusier had reportedly been enthused by La Maison Cubiste during the 1912 exhibition. "He saw in it important solutions for the problem of building with cement." Le Corbusier subsequently exhibited his model for Maison Citrohan (a mass production prototype) at the Salon d'Automne of 1922.[20] He later built the Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau[4] for the L'Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, 1925, Paris, the event which gave Art Deco its name.[21][22] The undecorated rectangular box of the Esprit Nouveau Pavilion, however, bore no resemblance to the Cubist House.

No buildings like the Cubist House were built in France, but the model did have an impact in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where architects wanted to show their independence from the Viennese style. In 1913 the Czech architect Pavel Janák was commissioned to reconstruct the facade of a large baroque house, the Fara House in the town of Pelhrimov in south Bohemia, in the cubist style. Janák redid the baroque facade by adding angular geometric forms similar to those on the model of the cubist house in Paris. Because of this quest for architectural independence from Austria, many art deco houses, mostly in the later more typical Deco style, are found in Prague and other cities in the Czech Republic. [23]

References

Notes and citations

- 1 2 Photograph of the Cubist House reproduced in The Sun. (New York, N.Y.), 10 Nov. 1912. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress

- ↑ Eve Blau, Nancy J. Troy, "The Maison cubiste and the meaning of modernism in pre-1914 France", in Architecture and Cubism, Montreal, Cambridge, MA, London: MIT Press−Centre Canadien d'Architecture, 1998, pp. 17−40, ISBN 0262523280

- ↑ Nancy J. Troy, Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier, New Haven CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1991, pp. 79−102, ISBN 0300045549

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christopher Green, Art in France: 1900–1940, Chapter 8, Modern Spaces; Modern Objects; Modern People, pp. 161-163, Yale University Press, 2000, 2003, ISBN 0300099088

- ↑ André Mare, Salon Bourgeois, Salon d'Automne, The Literary Digest, Doom of the Antique, New York City, November 30, 1912, p. 1012

- 1 2 Ben Davis, "Cubism" at the Met: Modern Art That Looks Tragically Antique, Exhibition: "Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection", Metropolitan Museum of Art, ArtNet News, 6 November 2014

- ↑ La Maison Cubiste, 1912

- ↑ Arwas 1992, p. 52.

- 1 2 Arwas 1992, p. 54.

- ↑ Goss, Jared. "French Art Deco". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- ↑ Kubistische werken op de Armory Show

- 1 2 Raymond Duchamp-Villon, listed in catalog of the New York Armory Show exhibit as number 609, Facade architectural, plaster, 1913, unidentified photographer. Walt Kuhn, Kuhn family papers, and Armory Show records, 1859-1984, bulk 1900-1949. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- ↑ "Catalogue of international exhibition of modern art: at the Armory of the Sixty-ninth Infantry, 1913, Duchamp-Villon, Raymond, Facade Architectural

- ↑ Victor Arwas, Frank Russell, Art Deco, publisher Harry N. Abrams. Inc. New York, 1980, pp. 52, 198, ISBN 0-8109-0691-0

- ↑ New-York tribune. (New York, N.Y.), 17 Feb. 1913. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress

- 1 2 Laurette E. McCarthy, Architecture, Interior Design, and "The Cubist Room" at the International Exhibition of Modern Art, Monday, May 13, 2013, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- ↑ Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, excerpt from Du Cubisme, 1912

- ↑ Salon d'Automne 1912, page from Excelsior reproduced

- 1 2 3 4 Walter Pach, A sculptor's architecture, 1913, Published by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. Kuhn family papers, and Armory Show records, 1859-1984, bulk 1900-1949. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- ↑ Alice T. Friedman, Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History, p. 110, Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0300117892

- ↑ Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

- ↑ Bevis Hillier, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s (Studio Vista/Dutton Picturebacks), 1968

- ↑ Benton 2002, pp. 191-192.

Bibliography

- Arwas, Victor (1992). Art Deco. Harry N. Abrams Inc. ISBN 0-8109-1926-5.

- Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine; Baddeley, Oriana (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

External links

- La maison cubistes, preparatory drawings, Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

- Douglas Cooper, The Cubist Epoch, pp. 100, 113, 239, Phaidon Press Limited 1970 in association with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art ISBN 0-87587-041-4