La Chasse (painting)

| English: The Hunt | |

| |

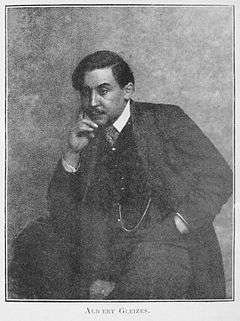

| Artist | Albert Gleizes |

|---|---|

| Year | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 123.2 cm × 99 cm (48.5 in × 39 in) |

| Location | Private collection |

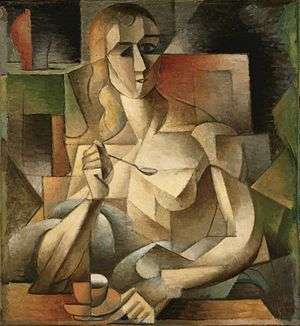

La Chasse, also referred to as The Hunt, is a painting created in 1911 by the French artist, theorist and writer Albert Gleizes. The work was exhibited at the 1911 Salon d'Automne (no. 610); Jack of Diamonds, Moscow, 1912; the Salon de la Société Normande de Peinture Moderne, Rouen, summer 1912; the Salon de la Section d'Or, Galerie La Boétie, 1912 (no. 37), Le Cubisme, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, 1953 (no. 64 bis), and several major exhibitions during subsequent years.

In 1913 the painting was reproduced in Les Peintres Cubistes, Méditations esthétiques by Guillaume Apollinaire.

Executed in a highly dynamic Cubist style, with multiple faceted views, the work nevertheless retains recognizable elements relative to its subject matter.

Description

La Chasse is an oil painting on canvas with dimensions 123.2 by 99 cm (48.5 x 39 inches) signed "Albert Gleizes", lower right. Painted in 1911.[1]

In this outdoor hunting scene the horizon line is almost on top of the canvas. Seven people are present, along with numerous animals.[2] A man with a hunting horn (Cor de chasse, la trompe du piqueur) can be seen in the foreground, his back turned to the viewer, with a group of hunting dogs to his right. Men on horses prepare for departure. Tension is in the air as the hunters and animals interact with one another. Another hunter on foot holds a gun in the background with a woman and child nearby and a village beyond. Spatial depth is minimized, the overall composition flattened, yet distances to the viewer are determined by the relationship of size; the further the object, the smaller in appearance. The faceting however does not partake in the size-distance relation, as one would expect. The hunting dogs to the lower right, for example, are treated with similar sized 'cubes' as the elements in the upper portions of the canvas; corresponding to the background. The hunting horn in the foreground is almost identical in size and in faceting to the trees in the distance. The same rounded shapes espouse the spherical surfaces formed by the horses heads.[2] This serves to counter the illusion of depth; each portion of the canvas equally important in the overall composition.

With its epic subject matter—far removed from neutral themes of the fruit dish, violin, and seated nudes exhibited by Picasso and Braque in the private boutique of Kahnweiler—The Hunt was destined form its very inception to be exhibited at the 1911 Salon d'Automne, at the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées; a huge public venue where several thousand viewers would see the works exhibited. Gleizes rarely painted still lifes, his epic interests usually finding sympathetic echos in more inclusive themes, such as La Chasse (The Hunt) and the monumental Harvest Threshing (Le Dépiquage des Moissons) of 1912. He wished to create a heroic art, stripped of ornament and obscure allegory, an art dealing on the one hand with relevant subjects of modern life: crowds, man and machines, and ultimately, the city itself (based on observations of the real world). And on the other, he wished to project tradition and accumulated cultural thought (based on memory).[3]

Gleizes continually stressed subjects of vast scale and of provocative social and cultural meaning. He regarded the painting as a manifold where subjective consciousness and the objective nature of the physical world could not only coincide but also be resolved.[3]

Here Gleizes not only created a synthetic landscape, in which elements are placed in unreal but symbolic relationships to each other, but also created a synthesis of social experience, showing two distinct types of human use of the land. Le Fauconnier painted a similar subject [Le Chasseur] the following year. Dorival has suggested that the treatment of the horses may well be an important source for those of Duchamp-Villon in 1914. [...] In his [1916] attempt to organize in plastic terms the abstract equivalent of his earlier broad panoramas, Gleizes reverted to the tilting planes reminiscent of smaller ones in such volumetric cubist works as The Hunt and Jacques Nayral, both of 1911. (Daniel Robbins, Guggenheim, 1964)[3][4]

1911 in brief

Meetings at the studio of Henri Le Fauconnier include young painters who want to emphasise a research into form, in opposition to the Divisionist, or Neo-Impressionist emphasis on color. The hanging committee of the Salon des Indépendants ensure that the works of these painters with similar ambitions be shown together. Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Henri Le Fauconnier, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Marie Laurencin are shown together in Room 41 (Salle 41). Guillaume Apollinaire has become an enthusiastic supporter of the new group. The result of the exhibition is a major scandal.[5]

The public is outraged by the apparent obscurity of the subject matter, and the predominance of the elementary geometrical shapes, which give rise to the term 'Cubism'. Although the term 'cube' has been used before with respect to the works of Metzinger (1906), Delaunay and Metzinger (1907), and Georges Braque (1908), this is the first time the word 'Cubism' is used. The designation becomes widespread as an artistic movement.[5][6][7][8] The term "Cubisme" is accepted in June 1911 as the name of the new school by Guillaume Apollinaire, speaking in the context of the Brussels Indépendants which includes works by Gleizes, Delaunay, Léger, Le Fauconnier and André Dunoyer de Segonzac.[5] Over the Summer of 1911, Gleizes, living and working in Courbevoie, is in close contact with Metzinger, who has recently moved to Meudon. Gleizes paints Le Chemin, Paysage à Meudon. The two have extensive conversations about the nature of form and perception. Both are discontent with classical perspective, which they feel give only a partial idea of the subject matter as experienced in life, seen in movement and from many different angles.[5]

1911 Salon d'Automne

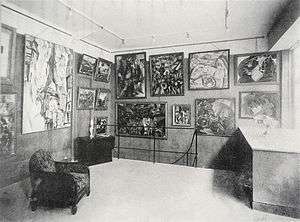

Following the Salon des Indépendants of early 1911, a new scandal is produced; this time in the Cubist room at the Salon d'Automne. Gleizes shows his Portrait de Jacques Nayral and La Chasse (The Hunt). Metzinger exhibits Le goûter (Tea Time). Other artists join the Salle 41 group: Roger de La Fresnaye, André Lhote, Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp, František Kupka, Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky and Francis Picabia, occupying rooms 7 and 8 of the salon. At about the time of this exhibition, through the intermediary of Apollinaire, Gleizes meets Picasso and sees his work along with that of Braque for the first time. He gives his reaction in an essay published in La Revue Indépendante. He considers that Picasso and Braque, despite the great value of their work, are engaged in an Impressionism of Form, i.e., they give an appearance of formal construction which does not rest on any clearly comprehensible principle. [...] We went to Kahnweiler's for the first time and saw the canvasses of Braque and Picasso which, rightly or wrongly, did not thrill us. Their spirit, being the opposite of our own. [...] And as far as Kahnweiler is concerned I never again put my foot in his boutique after this first visit in 1911.[5][9]

Through the Salon d'Automne, Gleizes becomes associated with the Duchamp brothers, Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Marcel Duchamp. The studios of Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon at 7 rue Lemaître in the Parisian suburb Puteaux, become, together with Gleizes' studio at Courbevoie, a regular meeting places for the Cubist group. The Puteaux studios share a garden with the studio of František Kupka, the Czech painter who is developing a non-representational style based on music and the progressive abstraction of a subject in motion.[5]

The critic Jean Claude writes, in a review of the 1911 Salon d'Automne titled Cubistes, Triangulistes, Trapézoïdistes et Intentionnistes, published in Le Petit Journal:

There is a cubist art... Those who doubt can go into the room where enclosed are the productions of wild beasts [fauves] who practice it...You will see there the Paysage lacustre, by Le Fauconnier, the Jeune homme et Jeune fille dans le printemps, mosaic of yellow, green, brown and pink, represented by small trapezoids of color, juxtaposed, the Paysage and Goûter by Jean Metzinger, classic cubist... A Marine by Lhote who invented the cubistic water. A figure nue by de la Fresnaye, which seems made with wooden bricks, and a mind-boggling Essai pour trois portraits by Fernand Léger. There too, Gleizes, a Chasse and a Portrait, which I find deeply regrettable, because the author, once, proved he had talent.

Non of this would have any importance if these horrors did not take up space that could be usefully occupied by other works, and if, above all, a few snobs did not offer them to the crowds as the last canons of modern beauty. But, really, extravagance, has it ever been art? And can art survive without beauty and without nobility? The Cubists and other "artists" will hardly make us forget Ingres, Courbet or Delacroix. So much for them. To be continued. (Jean Claude)[10]

Gleizes later recalled of the two major 1911 Salons:

It was at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1911 that, for the first time, the public was confronted with a collection of paintings which still did not have any label attached to them. [...]

Never had the critics been so violent as they were at that time. From which it became clear that these paintings—and I specify the names of the painters who were, alone, the reluctant causes of all this frenzy: Jean Metzinger, Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and myself—appeared as a threat to an order that everyone thought had been established forever. [...]

With the Salon d'Automne of that same year, 1911, the fury broke out again, just as violent as it had been at the Indépendants. I remember this Room 8 in the Grand Palais on the opening day. People were crushed together, shouting, laughing, calling for our heads. And what had we hung? Metzinger his lovely canvas entitled Le Goûter; Léger his sombre Nus dans un Paysage; Le Fauconnier, landscapes done in the Savoie; myself La Chasse and the Portrait de Jacques Nayral. How distant it all seems now! But I can still see the crowd gathering together in the doors of the room, pushing at those who were already pressed into it, wanting to get in to see for themselves the monsters that we were.

The winter season in Paris profited from all this to add a little spice to its pleasures. While the newspapers sounded the alarm to alert people to the danger, and while appeals were made to the public authorities to do something about it, song-writers, satirists and other men of wit and spirit, provoked great pleasure among the leisured classes by playing with the word 'cube', discovering that it was a very suitable means of inducing laughter which, as we all know, is the principle characteristic that distinguishes man from the animals.

The contagion, naturally, spread in proportion to the violence of the effort that was being put into stopping it. It quickly went beyond the frontiers of its country of origin. Public opinion throughout the world was occupied with Cubism. As people wanted to see what all the fuss was about, invitations to exhibit multiplied. From Germany, from Russia, from Belgium, from Switzerland, from Holland, from Austro-Hungary, from Bohemia, they came in great numbers. The painters accepted some of them and writers like Guillaume Apollinaire, Maurice Raynal, André Salmon, Alexandre Mercereau, the advocate-general Granié, supported them in their writings and in the talks they gave. (Albert Gleizes, 1925)[11]

In his review of the 1911 Salon d'Automne published in L'Intransigeant, written more as a counterattack in defense of Cubism, Guillaume Apollinaire expressed his views on the entries of Metzinger and Gleizes:

The imagination of Metzinger gave us this year two elegant canvases of tones and drawing that attest, at the very least, to a great culture... His art belongs to him now. He has vacated influences and his palette is of a refined richness. Gleizes shows us the two sides of his great talent: invention and observation. Take the example of Portrait de Jacques Nayral, there is good resemblance, but there is not one form or color in this impressive painting that has not been invented by the artist. The portrait has a grandiose appearance that should not escape the notice of connoisseurs. This portrait covers [revêt] a grandiose appearance that should not elude connoisseurs... It is time that young painters turn towards the sublime in their art. La Chasse, by Gleizes, is well composed and of beautiful colors and sings [chantant].[12][13]

Art market

Gleizes had always detested the art market falsified by a speculation on works of art imposed by the fantasy of fictitious bids to push up the prices in the public sales. When Léonce Rosenberg, whom Gleizes found the most sympathetic of the art dealers, offered to push up the price of his pre-war painting La Chasse, which was coming up for auction. Gleizes replied that he preferred to buy it himself and therefore wanted the price to be as low as possible. [5]

Related works

-

Early Netherlandish painting (South Netherlandish), c.1495-1505, The hunt of the unicorn. The Unicorn is killed and brought to the castle, from The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, tapestry, Wool warp, wool, silk, silver, 368.3 x 315 cm

-

Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1529, The Stag Hunt of the Elector Frederick the Wise, 80 × 114 cm

-

Gustave Courbet, 1858, The Hunt Breakfast, 207 x 325 cm

-

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_210.2_x_183.5_cm%2C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%2C_Boston..jpg)

Gustave Courbet, 1856, The Quarry (La Curée), oil on canvas, 210.2 x 183.5 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Eugène Delacroix, 1855, The Lion Hunt (La Chasse aux lions), Nationalmuseum, Sweden

-

Nicolas Poussin, 1634-1639, La Chasse de Méléagre et Atalante (Le Départ pour la chasse), 160 x 360 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

-

Évariste Vital Luminais, before 1879, Départ pour la Chasse dans les Gaules (Departure for the Hunt in Gaul), oil on canvas, 150 x 118 cm

-

Giovanni di Francesco, 1450, La Chasse (The Hunt), Musée des Augustins, Toulouse

-

Peter Paul Rubens, c.1615-1621, Wolf and Fox Hunt, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Peter Paul Rubens, 1616, Hunting and animals

-

François Lemoyne, 1723, Hunting Picnic

-

Gaston Fébus, Chasse aux lièvres. Livre de chasse, 1387, Musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris

-

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), 1511, Expulsion of Heliodorus from the temple (Héliodore chassé du Temple), The Vatican, Apostolic Palace, Rome (detail)

-

Jean-François de Troy, 1737, Hunt Breakfast and Death of a Stag

-

%2C_1405-1410%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_national_du_Moyen_%C3%82ge%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_de_Cluny%2C_Paris.jpg)

Deer hunting scene, Le Livre de chasse de Gaston Phébus (original work written in 1387-89), 1405-1410, Musée national du Moyen Âge, Musée de Cluny, Paris

-

Eugène Fromentin, 1857, Départ pour la chasse (Departure for the Hunt)

Provenance

- René Gaffé, Brussels.

- Edouard Labouchère, Paris, until at least 1965.

Exhibitions

- Paris, Salon d'Automne, October - November 1911, no. 610.

- Moscow, Valet de Carreau (Jack of Diamonds), January 1912, no. 42.

- Rouen, Société Normande de Peinture Moderne, June - July 1912, no. 89.

- Paris, Galerie de la Boétie, Salon de la Section d'Or, October 1912, no. 37.

- La Section d'Or exhibition, 1925, Galerie Vavin-Raspail, Paris

- Paris, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Le Cubisme, 1953, no. 64bis.

- Paris, Galerie Knoedler, Les Soirées de Paris, 1958, no. 13.

- Munich, Haus der Kunst, Von Bonnard bis heute, les Chefs d'Oeuvre des collections privées françaises, 1961, no. 51.

- Grenoble, Musée de Peinture et de Sculpture, Albert Gleizes et Tempête dans les Salons, 1910-1914, June - August 1963, no. 5 (illustrated in the catalogue).

- New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Albert Gleizes, 1881-1953, A Retrospective Exhibition, 1964, no. 28 (illustrated in the catalogue).

- Paris, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Albert Gleizes, 1881-1953, Exposition rétrospective, December 1964 - January 1965, no. 12 (illustrated in the catalogue); this exhibition later travelled to Dortmund, Museum am Ostwall.

Literature

- G. Apollinaire, L'Intransigeant, 10 October 1911.

- J. Granié, 'Au Salon d'Automne', Revue d'Europe et d'Amerique, Paris, October 1911.

- A. Gleizes, Souvenirs le Cubisme 1908-1914, Cahiers d'Albert Gleizes, Lyon, 1957, pp. 18, 26-28 (illustrated as the frontispiece).

- B. Dorival, Les Peintres du XXème siècle, Paris, 1957, p. 76.

- P. Alibert, Albert Gleizes, naissance et avenir du cubisme, Saint-Etienne, 1982, p. 71 (illustrated).

- P. Alibert, Gleizes, Biographie, Paris, 1990, p. 55.

- A. Varichon, Albert Gleizes, Catalogue raisonné, vol. I, Paris, 1998, no. 374 (illustrated p. 136).

References

- ↑ Christie's, Albert Gleizes, 1911, La Chasse, oil on canvas, 123.2 x 99 cm, Lot description

- 1 2 P. Alibert, Albert Gleizes, naissance et avenir du cubisme, Saint-Etienne, 1982, p. 71

- 1 2 3 Robbins, Daniel, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Albert Gleizes, 1881-1953, A Retrospective Exhibition, 1964

- ↑ Dorival, B., Les Peintres du XXe siecle, Paris, 1957, p. 76

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes, Chronology of his life, 1881-1953

- ↑ Robert Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1968

- ↑ Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, p. 11

- ↑ Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs: le Cubisme, 1908-1914, Cahiers Albert Gleizes, Association des Amis d'Albert Gleizes, Lyon, 1957. Reprinted, Association des Amis d'Albert Gleizes, Ampuis, 1997

- ↑ Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, La Revue Indépendante, n°4, September 1911

- ↑ Jean Claude, Le Salon d'Automne, Cubistes, Triangulistes, Trapézoïdistes et Intentionnistes, Le Petit Parisien, Numéro 12756, 2 October 1911, p. 5. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ↑ Albert Gleizes, The Epic, From immobile form to mobile form, translation by Peter Brooke. Originally written by Gleizes in 1925 and published in a German version in 1928, under the title Kubismus, in a series called Bauhausbücher

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire, Le Salon d'Automne, L'Intransigeant, Numéro 11409, 10 October 1911, p. 2. Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ↑ Tate, London, Albert Gleizes, Portrait de Jacques Nayral, 1911

External links

- Albert Gleizes, Etude pour La Chasse, Centre Pompidou, MNAM, inventory number: AM 1974-173

- Fondation Albert Gleizes

- Ministère de la Culture (France) – Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine, Albert Gleizes

- Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Grand Palais, Agence photographique