L'Oiseau bleu (Metzinger)

| English: The Blue Bird | |

_oil_on_canvas%2C_230_x_196_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Art_Moderne_de_la_Ville_de_Paris..jpg) | |

| Artist | Jean Metzinger |

|---|---|

| Year | 1912-13 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 230 cm × 196 cm (90.5 in × 77.2 in) |

| Location | Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris |

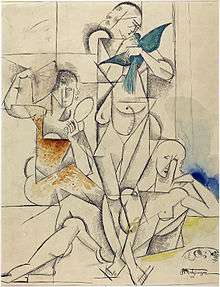

L'Oiseau bleu (also known as The Blue Bird and Der Blaue Vogel) is a large oil painting created in 1912–1913 by the French artist and theorist Jean Metzinger (1883–1956); considered by Guillaume Apollinaire and André Salmon as a founder of Cubism, along with Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. L'Oiseau bleu, one of Metzinger's most recognizable and frequently referenced works, was first exhibited in Paris at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1913 (n. 2087), several months after the publication of the first (and only) Cubist manifesto, Du «Cubisme», written by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes (1912). It was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in Berlin (titled Der blaue Vogel, n. 287). Apollinaire described L'Oiseau bleu as a 'very brilliant painting' and 'his most important work to date'. L'Oiseau bleu, acquired by the City of Paris in 1937, forms part of the permanent collection at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.[1]

Description

L'Oiseau bleu is an oil painting on canvas with dimensions 230 x 196 cm (90.5 by 77.2 in). The work represents three nude women in a scene that contains a wide variety of components. L'Oiseau bleu, writes Joann Moser, uses a wealth of anecdotal detail "which comprises a compendium of motifs found in earlier and later paintings by Metzinger: bathers, fan, mirror, ibis, necklace, a boat with water, foliage and an urban scene. It is a mélange of interior and exterior elements integrated into one of Metzinger's most intriguing and successful compositions."[2]

The central standing 'foreground' figure is shown affectionately holding in both hands a blue bird (thus the title of the painting). The reclining figure wearing a necklace shown in the lower center of the canvas is placed next to a pedestal fruit bowl and another bird with the unmistakable coloration of the rare Scarlet ibis (L'Ibis rouge), a rich symbol for both exoticism and fashion. Costume designers for Parisian cabarets such as Le Lido, Folies Bergère, the Moulin Rouge and haute couture houses in Paris during the 1910s used the feathers of the scarlet Ibis in their shows and collections. The Ibis is a bird to which the ancient Egyptians paid religious worship and attributed to it a 'virgin purity'.[3][4] A mysterious pyramidal shape is seen as if through a porthole to the right of the reclining figure's head, though it remains a matter of speculation whether there exists any relation to the ibis or pyramids of ancient Egypt. In front of the pyramid appears a shape that resembles a sundial, perhaps meant as the element of time, or 'duration', as the clock placed in the upper right hand corner of his Nude of 1910.[5]

Two other birds, in addition to the blue bird and scarlet ibis can be seen in the composition, one of which resembles a green heron. A large steamship can be seen bellowing gaseous vapor from its funnel in the distant sea or ocean, and a smaller boat (or canot) is visible below.

On the left half of Metzinger's L'Oiseau Bleu, holding in her right hand a yellow fan (éventail) is a sitting nude who in her left hand holds a mirror into which she gazes. In the rest of the scene, various items and divers elements are placed, including in the upper center (practically at the highest point of the painting) the Sacré-Cœur Basilica, located at the summit of the butte Montmartre, the highest point of the city. This popular monument is just up the hill from where Metzinger lived and worked (Rue Lamarck) prior to his move to Meudon around 1912. It is also a short distance from Le Bateau-Lavoir, widely known as the birthplace of Cubism.

The flag

Edward F. Fry writes in Cubism (1978): "Three female nudes are in various postures, and the blue bird is held by the uppermost figure; in other parts of the composition are numerous birds, grapes in a dish on a table, the striped canopy of a Paris cafe, the dome of Sacre-Coeur in Montmartre, and a ship at sea."[6] (Bold added). Noticeably, the 'striped canopy' to which Fry refers has the same color pattern as the American flag. Recall that L'Oiseau bleu was painted as the International Exhibition of Modern Art (the Armory Show) in New York was beginning to materialize; when Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn came to Paris in the fall of 1912 to select works for the Armory Show, with the help of Walter Pach.[7] The paintings of Metzinger, however, did not appear at the exhibition (to the surprise of many in his entourage); and this despite Picasso's 1912 recommendation. In a note to Kuhn, Picasso's handwritten list of artists recommended for the Armory Show include Gris, Metzinger, Gleizes, Léger, Duchamp, Delaunay, Le Fauconnier, Laurencin, La Fresnaye and Braque.[8] He did however exhibit at the Exhibition of Cubist and Futurist Pictures, Boggs & Buhl Department Store, Pittsburgh, July 1913. His Portrait of an American Smoking (Man with a Pipe), 1911–12 (Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin[9]) was reproduced on the front cover of the catalogue.[10] It is highly likely, since Walter Pach knew practically all the artists in the exhibition (a good friend of Metzinger and other members of the Section d'Or group; e.g., Gleizes, Picabia and the Duchamp brothers), that he had something to do with the organization of the show. Sponsored by the Gimbel Brothers department store from May through the summer of 1913 the Cubist and Futurist show toured Milwaukee, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and New York.[11]

Metzinger had already been interviewed, circa 1908, by Gelett Burgess for his Wild Men of Paris article, published in The Architectural Record, May 1910 (New York).[12] In 1915 (8 March - 3 April) Metzinger exhibited at the Third Exhibition of Contemporary French Art—Carstairs (Carroll) Gallery, New York—with Pach, Gleizes, Picasso, de la Fresnaye, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Derain, Duchamp, Duchamp-Villon and Villon.[11][13]

Metzinger would soon exhibit six works in New York at the Montross Gallery, 550 Fifth Avenue (4–22 April 1916) with Gleizes, Picabia, Duchamp, and Jean Crotti.[14][15][16] In 1917 Metzinger exhibited at the People's Art Guild (founded in 1915 to disseminate art to the masses) in New York, with Pach, Picabia, Picasso, Derain and Joseph Stella. In December 1917 Metzinger exhibited at the Exhibition of Paintings by the Moderns, held at Vassar College (located in the heart of the Hudson Valley in New York), with Pach, Derain, Edward Hopper, Diego Rivera and Max Weber.[11]

Duchamp, Picabia, Gleizes and his wife (via Hamilton Bermuda) would soon leave for New York where they would stay an extended period of time. Maurice Metzinger, Jean's brother, made several trips to the United States, in 1906, 1910 and would soon move there permanently in pursuit of his career as a Cellist.[17] In light of the turmoil surrounding his non-acceptance at the Armory show, his brother's experiences in New York, his soon to be exposition at the Cubist Exhibition, Boggs & Buhl's, and the representation of a steamship in the upper right quadrant of L'Oiseau bleu, it would not be out of the question that Metzinger made reference to the American flag (as opposed to a red and white stripped canopy of a Parisian café as suggested by Fry).

This would be remarkable in light of the growing trend of Nationalism surrounding modern art exhibitions in Paris, within which Metzinger was recognized as a French Cubist, and his work, in the French tradition: 'cubisme dans une tradition française'.[18] Painting an American flag might have been seen as provocative, especially so as Roger de La Fresnaye was painting French flags: Fourteenth of July, 1913-14 (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX), and The Conquest of the Air, 1913 (Museum of Modern Art, New York),[19][20] two of his most original contributions to the diverse salons.[21] André Lhote appears to show both the flag of the United Kingdom and the stripes of the American flag in his L'Escale, of 1913 (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris). The Futurist Gino Severini, too, included the French flag in his 1913 painting Train of the Wounded.[22]

Divisionism to Multiple perspective

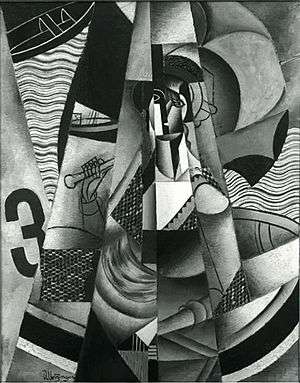

As in the works of Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge there is no smooth transition between the elements and sections of Metzinger's painting, but when sutured together (with the eye) in succession or simultaneously a dynamic ensemble emerges. The composition is divided, fragmented, splintered or faceted into series, not only of individual rectangles, squares or 'cubes' of color, but into individual planes or surfaces delineated by color and form. Just as other paintings by Metzinger of the pre-war period (such as En Canot, 1913) there is some continuity that transits between the foreground and background, blending perspective of objects close and far, the notion of depth perception has not been abolished, i.e., the spatial attributes of the scene have not been flattened, yet there is no absolute frame of reference.

Though not the first painting by Jean Metzinger to employ the concept of multiple perspective—three years had passed since he first propounded the idea in Note sur la peinture, published in 1910—L'Oiseau bleu arguably exemplifies the extreme, a maxima, a summum bonum of such pictorial processes, while still maintaining elements of recognizable form; the extreme activity of geometric faceting visible in L'Oiseau bleu is not frenzied to the point that any understandable link between physicality or naturalness is lost. Yet, what is achieved is, of course, fundamentally anti-naturalistic; at great distance from the appearance of the natural world.

Aimed at a large audience (the Salon des Indépendants, rather than a gallery setting), L'Oiseau bleu deliberately sets out to agitate and confront the standard expectation of art, in an attempt to implicated the viewer, to transfer beauty and elegance into a fresh cohesive dialogue that most accurately represents Modernism—one that is in tune with the intricacies of modern life, one that describes Cubism, his Cubism, whose order was only a phase in a continuous process of change.

To achieve his goal, Metzinger raises the concept of mobile perspective (as opposed to single-point perspective of the Renaissance) to a poetic principle: a form of literary art which uses the aesthetic qualities of iconography to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, the prosaic ostensible meaning. L'Oiseau bleu contains something that Metzinger spoke of as early as 1907; a "chromatic versification", as if for syllables. The rhythm of its pictorial phraseology translates the diverse emotions aroused by nature (in the words of Metzinger).[24] L'Oiseau bleu no longer represented nature as seen, but was a complete byproduct of the human 'sensation.' A departure from nature it was, and a departure from all that had been painted to date it was too.

Metzinger's Divisionist technique had its parallel in literature. For him, there was an emblematic alliance between the Symbolist writers and Neo-Impressionism. Each brushstroke of color was equivalent to a word (or "syllable"). Together the pigments formed sentences (or "phrases") which translated the various emotions that nature would pass on to the artist. This is an important aspect of Metzinger's early work, and an important aspect of Metzinger's entire artistic output (as a painter, writer, poet, and theorist). Already then, Metzinger coupled Symbolist/Neo-Impressionist color theory with Cézannian perspective, beyond not just the preoccupations of Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, but beyond too the preoccupations of his avant-garde entourage.[25]

"I ask of divided brushwork not the objective rendering of light, but iridescences and certain aspects of color still foreign to painting. I make a kind of chromatic versification and for syllables I use strokes which, variable in quantity, cannot differ in dimension without modifying the rhythm of a pictorial phraseology destined to translate the diverse emotions aroused by nature." (Metzinger, 1907)

An interpretation of this statement was made by Robert L. Herbert: "What Metzinger meant is that each little tile of pigment has two lives: it exists as a plane where mere size and direction are fundamental to the rhythm of the painting and, secondly, it also has color which can vary independently of size and placement." (Herbert, 1968)[24][26]

During Metzinger's Divisionist period, each individual square of pigment associated with another of similar shape and color to form a group; each grouping of color juxtaposed with an adjacent collection of differing colors; just as syllables combine to form sentences, and sentences combine to form paragraphs, and so on. Now, the same concept formerly related to color has been adapted to form. Each individual facet associated with another adjacent shape form a group; each grouping juxtaposed with an adjacent collection of facets connect or become associated with a larger organization—just as the association of syllables combine to form sentences, and sentences combine to form paragraphs, and so on—forming what Metzinger described as the 'total image'.[25][27]

Underlying geometric armature

.jpg)

Though the primary role of Metzinger's syntax was played by the relations of its intricate parts within the whole, there was another key factor that emerged: the mobile underlying geometric armature organized as a dynamic composition of superimposed planes. Metzinger, Juan Gris and to some extent Jacques Lipchitz, would develop this concept further during the war; something Gleizes would notice when he returned to Paris from New York, and develop further still in Painting and its Laws (La Peinture et ses lois), written in 1922 and published in 1923. In that text Gleizes would attribute to this underlying armature 'objective notions of translation and rotation', words in which 'movement is implicit'.[28][29]

In this sense Metzinger's L'Oiseau bleu was a precursor in its genre, more so perhaps than his Le goûter (Tea Time) of 1911, La Femme au Cheval, 1911–12, or Dancer in a café (Danseuse) of 1912.[30][31]

Now, the emergence of the 'total image' arises out of a multiplicity of relatively simple interacting planes or surfaces, loosely based on the Golden triangle and Fibonacci spiral. Whereas before, each disconnected element would unite forming complex relationships as a collective, now (and progressively), the collective components would be organized into an abstract mathematical concept that is much more general; giving rise to a global topology. This underlying geometric armature would facilitate the union of a set (or sets) of complex structures on a given orientable surface.

Symbolism and interpretations

In The Introduction to Metaphysics (1903) Henri Bergson described in his theory of images how uniting a collection of disparate images acts on the consciousness and intuition, creating an alogical disposition. The Symbolist poet Tancrède de Visan, who prior to 1904 and some time leading up to 1911 attended the lectures of Bergson at the College de France, met regularly with the Cubists at the poet Paul Fort's soirees at the fashionable La Closerie des Lilas. He related Bergson's notion of 'accumulated successive images' to the writings of Maurice Maeterlinck circa 1907, and in 1910 advocated the technique in Vers et Prose.[32]

In Note su la peinture of the same year Metzinger argues that Delaunay's Tour Eiffel combines several different views captured throughout the day in one image. 'Intuitive, Delaunay has defined intuition as the brusque deflagration of all the reasonings accumulated each day'.[32] The following year, in Cubisme et Tradition (1911) Metzinger writes of the immobility of paintings of the past, and that now, artists permit themselves the liberty of 'moving around the object to give, under the control of intelligence, a concrete representation derived from several successive aspects.' He continues, 'The painting possesses space, and now it also reigns in the duration' ["voilà qu'il règne aussi dans la durée"].,[33][34] With motion and time, intuition and consciousness, Metzinger could now claim his art had moved closer to nature, closer to a true, yet subjective, reality.

Parallel to the theories of Bergson, embraced by Metzinger, Gleizes and other members of the Section d'Or, Maeterlinck’s ideas became of interest. Bolstered by mathematics, Reimannian geometry, and new discoveries in science that revealed existence of unseen realms (such as X-rays), and attracted to the concept of extra dimension (in addition the three spatial dimensions: the fourth dimension), Metzinger likely responded positively to Maeterlinck’s popular play L’Oiseau bleu (written in 1908), finding in it, perhaps, the analogy to the Cubist quest for higher realities.[35]

Maeterlinck’s play premiered in Moscow in 1908, New York 1910, and on 2 March 1911 the play premiered in Paris at the Théâtre Réjane (owned and run by the French actress Réjane from 1906 to 1918). It has since been turned into several films. The French composer Albert Wolff wrote an opera (first performed at the N.Y. Metropolitan, 27 December 1919, in the presence of Maeterlinck) based on Maeterlinck's original 1908 play. Due to the early popularity of the play and Metziger's various interests in science and Symbolism, and due to the fact the his 1913 painting bares the same name as the play, it is relatively safe to assume that Metzinger was familiar with the work of Maeterlinck.

Edward Fry’s commented in Cubism[36] that Metzinger’s L’Oiseau bleu has "no significant connection with Maeterlinck’s 1910 play of the same name” may not be entirely justified.[35] Aside from the presence of the blue bird (The Blue Bird of Happiness in Maeterlinck's play) there is no iconographic evidence relating to the painting to the play, but at the very least a connection between Maeterlinck and Symbolism, with Bergson and Cubism, has been established through Tancrede de Visan.[35][37]

"The Cubists also found support in Maeterlinck for their ideas regarding successive images and simultaneity. Contemporary critics like Visan recognized the parallel between Bergson and Maeterlinck, claiming that Maeterlinck had anticipated Bergson’s technique of successive images in Serres chaudes. While Bergson argued that the artist must induce an alogical state in the beholder by juxtaposing images as disparate as possible to enable the spectator to reconstruct his or her original intuition, Maeterlinck took the same approach in Serres chaudes, according to Visan. Furthermore, Maeterlinck used words and gestures in unusual ways and placed them in strange contexts with the same aim in mind. Maeterlinck’s highly popular L’Oiseau bleu and other writings, including Le temple enseveli, espoused a continuity of time previously suggested by Bergson. In addition, the faceted diamond of L’Oiseau bleu not only gave the children “true sight” that closely mimicked the X-ray, but also allowed them to perceive distant times and places. Clearly responding the play, Metzinger, in his painting of the same name, breaks the objects into facets and reveals a simultaneous view of places separated by great distance. Just as Poincaré advocated that a combination of multiple perspectives could represent a higher-dimensional object, Metzinger must have seen a parallel with Maeterlinck’s diamond—a faceted object that revealed higher reality". (Laura Kathleen Valeri, 2011)[35]

LIGHT: "We are in the Kingdom of the Future," said Light, a character in Meaterlinck's play, "in the midst of the children who are not yet born. As the diamond allows us to see clearly in this region which is hidden from men, we shall perhaps find the Blue Bird here..."[38]

THE FAIRY: (Pointing to the diamond) "When you hold it like this, do you see?… One little turn more and you behold the past…. Another little turn and you behold the future…"[38]

LIGHT: "We are in the Kingdom of the Future, in the midst of the children who are not yet born. As the diamond allows us to see clearly in this region which is hidden from men, we shall very probably find the Blue Bird here..."[38]

The enchanted diamond in The Blue Bird, when turned, has the virtue of setting free the spirits temporarily, a diamond " which opens your eyes" and "makes people see", even "the inside of things".[38]

The same year that he painted L’Oiseau bleu Metzinger wrote: 'We will not consider the forms as signs of an idea, but as living portions of the universe.' (1913)[39]

Interestingly, Guillaume Apollinaire, in a poem written in 1907 entitled La Tzigane, writes of a blue bird: "Et l'oiseau bleu perdit ses plumes Et les mendiants leurs Avé".[40] He does so again in 1908 in another poem, entitled Fiançailles: "Le printemps laisse errer les fiancés parjures, Et laisse feuilloler longtemps les plumes bleues, Que secoue le cyprès où niche l'oiseau bleu".[41] And yet again, this time in 1918, in Un oiseau chante: Moi seul l'oiseau bleu s'égosille, Oiseau bleu comme le coeur bleu, De mon amour au coeur céleste".[42]

The Blue Bird is also 1910 silent film, based on the play by Maurice Maeterlinck and starring Pauline Gilmer as Mytyl and Olive Walter as Tytyl. It was filmed in England. The original Broadway production of "The Blue Bird" or "L'Oiseau Bleu" by Maurice Maeterlinck opened at the New Theatre in New York (followed by the Majestic Theater) on October 1, 1910 and closed on January 21, 1911. Revivals were produced in 1911 and 1924.[43][44]

L'Oiseau bleu (Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky)

L'Oiseau bleu et la Princesse Florine appear in a Pas de deux, Act III of The Sleeping Beauty, a ballet in three acts first performed in 1890. The music was by Pyotr Tchaikovsky (his Opus 66). The original scenario was conceived by Ivan Vsevolozhsky, and is based on Charles Perrault's La Belle au bois dormant. Marius Petipa choreographed the original production. The premiere performance took place at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in 1890.

Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, working for Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev and first performed in Paris by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes: The Firebird (L'Oiseau de feu) (1910), Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). The rhythmic structure of these compositions were largely responsible for Stravinsky's enduring reputation as a musical revolutionary who pushed the boundaries of musical design.

Stravinsky's admiration for Tchaikovsky is well documented. Stravinsky's music has often been compared with Cubism. His path often crossed with the Cubists,[46] notably Picasso and Gleizes, and through Ricciotto Canudo contributed to and became closely associated with the pro-Cubist publication Montjoie.,[47][48] Gleizes published an article in Canudo's Montjoie entitled Cubisme et la tradition, 10 February 1913.[49] It was through the intermediary of Ricciotto Canudo that Gleizes would meet the artist Juliette Roche (soon to become Juliette Roche-Gleizes); a childhood friend of Jean Cocteau. Stravinsky would later collaborate with both Picasso (Pulcinella, 1920), and Cocteau (Oedipus Rex, 1927).

Albert Gleizes painted the Portrait of Igor Stravinsky in 1914.[50]

The connection between Tchaikovsky's L'Oiseau Bleu and Metzinger's L'Oiseau Bleu is not entirely far fetched in light of the close association between Stravinsky and both circles: that of the Russian Ballets and that of the Cubists. At the opening night of the Ballets Russes in Paris, May 1909, Vaslav Nijinsky's performed with Tamara Karsavina in the Bluebird pas de deux.[51][52]

L'Oiseau bleu (Madame d'Aulnoy)

The title L'Oiseau bleu (The Blue Bird) can be traced back to a French literary fairy tale by Madame d'Aulnoy (1650/1651 – 4 January 1705), published in 1697. When d'Aulnoy termed her works contes de fées (fairy tales), she originated the term that is now generally used for the genre.[53] Prince Charming, in the story, is transformed by the fairy godmother into a blue bird. Aside from the subject of the title of Madame d'Aulnoy's story, there is further iconographic evidence in Metzinger's painting that suggests a link between the two. The first relates to the woman gazing into a mirror on the left side of Metzinger's painting.

In the Madame d'Aulnoy 1697 story it is written:

'The entire valley was a mirror. Around the valley there were more than sixty thousand women who gazed at themselves with extreme pleasure... Each saw herself as she wanted to be: the redhead seemed blonde, the brunette had black hair, the old thought she was young, the young didn't become old; finally, all defects were so well hidden that the people came from all over the world'.[54]

With reference to the fruit visible in Metzinger's work, a link could be established as articulated in d'Aulnoy's tale: 'As soon as the day broke, the [blue] bird flew deep into the tree where fruits served as food.'[54]

And with reference to the necklace worn by Metzinger's reclining figure, a comparison could be made with d'Aulnoy's story:

'No day passed without [the Blue Bird – King Charming] bringing a present [présent] to Florine: sometimes a perl necklace, or the brightest and well-made rings, fastened with diamonds, an official marking [des poinçons], with bouquets of precious cut gems, that mimic the colors of flowers, pleasant books, medals, finally, she had a collection of wonderful treasures'.[54]

Diversity and inspiration

It is difficult to ascertain to what extent Metzinger was influenced, moved, provoked or inspired by the works of Maeterlinck, Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky or d'Aulnoy. What does emerge is the closer iconographic detail visible in Metzinger's painting with the original version of L'Oiseau bleu (the first version, that also happens to be French, of 1697) by Madame d'Aulnoy. In fact, it is the only version of L'Oiseau bleu that appears to be mirrored iconographically in Metzinger's painting.

The fact that the difficulty even exists attests to the diversity of Metzinger's interest in widely disparate subjects, widely faceted interests and sensitivities, ranging from women to fashion, from literature to science, in passing through mathematics, geometry, physics, metaphysics, philosophy, nature, classical music, opera, dance, theater, cafés, travel and poetry. He was open to all the idioms that he considered genuinely popular.[55]

- 'The art that does not pass leans on mathematics' Metzinger wrote, 'Whether the result of patient study or of flashing intuition, it alone is capable of reducing our diverse, pathetic sensations to the strict unity of a mass (Bach), a fresco (Michelangelo), a bust (antiquity)."[55]

"Jean Metzinger, then" wrote art historian Daniel Robbins, "was at the center of Cubism, not only because of his role as intermediary among the orthodox Montmartre group and right bank or Passy Cubists, not only because of his great identification with the movement when it was recognized, but above all because of his artistic personality. His concerns were balanced; he was deliberately at the intersection of high intellectuality and the passing spectacle."[55]

Exhibitions

%2C_Andr%C3%A9_Lhote_(right)%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Art_Moderne_de_la_Ville_de_Paris.jpg)

Salon des Indépendants, 1913

The Salon des Indépendants was held 19 March through 18 May, the Cubist works were shown in room 46. Metzinger exhibited three works: Paysage, Nature Morte, and his large L'Oiseau bleu, n. 2087 of the catalogue[56] — Albert Gleizes exhibited three works: Paysage, Le port marchand, 1912, Art Gallery of Ontario, and Les Joueurs de football (Football Players) 1912-13, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. m. 1293 of the catalogue[57] — Robert Delaunay, L'équipe du Cardiff F.C., 1912–13, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, n. 787 of the catalogue[58] — Fernand Léger, Le modèle nu dans l'atelier (Nude Model In The Studio) 1912-13, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York — Juan Gris, L'Homme dans le Café (Man in Café) 1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art.[59]

In room 45 hung the works of Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, František Kupka, Morgan Russell and Macdonald-Wright. This was the first exhibition where Orphism and Synchromism were emphatically present. Apollinaire in L'Intransigeant mentioned la Salle hollandaise (room 43), which included Jacoba van Heemskerck, Piet Mondrian, Otto van Rees, Jan Sluyters en Leo Gestel and Lodewijk Schelfhout.

Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon, Berlin, 1913

20 September — 1 November 1913: Metzinger exhibited L'Oiseau bleu (Der Blaue Vogel), catalogue number 287, at Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in Berlin, an exhibition organized by Herwarth Walden (Galerie Der Sturm). Artists include Henri Rousseau, the Delaunays, Gleizes, Léger, Marcoussis, Archipenko, Picabia, Kandinsky, Severini, Chagal, Klee, Jawlensky, Russolo, Mondrian and others.[60]

Following the Salon d'Automne of 1913 in Paris this show took place at Potsdamer Strasse 75, Berlin. 75 artists from 12 countries exhibited 366 works. This exhibition was supported financially by the manufacturer and art collector Bernhardt Köhler.[61]

Apollinaire described the Herbst salon of 1913 as the first Orphist Salon. There were many works by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, in addition to abstract works by Picabia and Cubist works by Metzinger, Gleizes, Léger and a large number of Futurist paintings. This exhibition was a turning-point in Apollinaire’s artistic strategy for Orphism. After becoming entangled through some remarks in an argument between Delaunay and Umberto Boccioni about the ambiguousness of the term ‘simultaneity’ he did not use the term Orphism again in his art related articles. The artists labeled Orphists also brushed off the term and developed stylistic trends of their own.[62]

Paris International Exposition, 1937

The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, dedicated to Art and Technology in Modern Life, was held from May 25 to November 25, 1937, in Paris, France. L'Oiseau Bleu (n. 11) was exhibited in a show entitled Les Maitres de I'Art Indépendant 1895-1937, held at the Petit Palais, in Paris. L'Oiseau Bleu was purchased by la Ville de Paris (the City of Paris) the same year.[63] The Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, within the Palais de Tokyo, which would soon house L'Oiseau Bleu, was designed for the International Art and Technical Exhibition of 1937. This exhibition provided the opportunity for some remarkable acquisitions including: The Dance (La Danse) by Henri Matisse, Nude in the bath and The Garden by Pierre Bonnard, The Cardiff Team (L'équipe de Cardiff ) by Robert Delaunay, The River by André Derain, Discs (Les Disques) by Fernand Léger, The Stopover (l'Escale) by André Lhote, L'Oiseau Bleu (The Blue Bird) by Jean Metzinger, Les Baigneuses (The Bathers) by Albert Gleizes, four Artists’ Portraits by Édouard Vuillard, which still number among the museum’s masterpieces, not forgetting the large murals by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Albert Gleizes and Jacques Villon, acquired during the exhibition (donated by the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in 1939).[64][65]

For this same massive exhibition Metzinger was commissioned to paint a large mural, Mystique of Travel, which he executed for the Salle de Cinema in the railway pavilion.[66]

Paris 1937, l'art indépendant, 1987

Paris 1937, l'art indépendant: MAM, Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris. From 12 June to 30 August 1987 L'Oiseau bleu (n. 254) was exhibited at the Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris in a show entitled Paris 1937, l'art indépendant, held for the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Paris International Exposition of 1937. At the 1987 memorial exhibition, consisting of 122 artists exhibiting 354 works, there were displayed considerably less works than the 1,557 presented in 1937.[67]

L'Oiseau Bleu postage stamp

For the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Cubist manifesto Du "Cubisme", 1912-2012, a French postage stamp was printed with the image of Metzinger's L'Oiseau bleu.[68] A postage stamp representing Le Chant de guerre, portrait de Florent Schmitt (1915) by Albert Gleizes was also printed,[69] in a series that includes stamps representing the works of other Cubists such as Roger de La Fresnaye, Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso and others.[70] For the same occasion in 2012 the Musée national de la Poste (France) (the logo of which is a blue bird)[71] mounted an exhibition entitled Gleizes-Metzinger. Du Cubisme et après dedicated to Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, in which appeared the works of other members of the Section d'Or group.[72]

1913 in context

Niels Bohr presents his quantum model of the atom.[73][74][75] — Robert Millikan measures the fundamental unit of electric charge — Georges Sagnac demonstrates the Sagnac effect, showing that light propagates at a speed independent of the speed of its source.[76][77][78] — William Henry Bragg and William Lawrence Bragg work out the Bragg condition for strong X-ray reflection — Publication of the 3rd volume of Principia Mathematica by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell, one of the most important and seminal works in mathematical logic and philosophy — February 17 - The Armory Show opens in New York City. It displays works of artists who are to become some of the most influential painters of the early 20th century — Marcel Proust, Swann's Way — D. H. Lawrence, Sons and Lovers — Franz Kafka, The Judgement — Blaise Cendrars, La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France — Guillaume Apollinaire, Alcools: Poemes 1898-1913, edited by Tristan Tzara[79] — Blaise Cendrars, La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France, a collaborative artists' book with near abstract pochoir print by Sonia Delaunay-Terk — Francis Jammes, Feuilles dans le vent[80] — 29 May - Igor Stravinsky's ballet score The Rite of Spring is premiered in Paris — 12 December - Vincenzo Perugia tries to sell Mona Lisa in Florence and is arrested. Apollinaire had been a suspect in Paris for its theft — 30 December - Italy returns Mona Lisa to France — 23 September - Aviator Roland Garros flies over the Mediterranean

Further reading

- Fry, Edward F., Cubism, Londres, Thames and Hudson, 1966, p. 191

- Les Cubistes, Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1973, cat 156 p. 83

- Chefs-d'oeuvre du Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris-Musées et SAMAM, 1985, pp. 38, 140

- Caffin Madaule, Liliane, Maria Blanchard 1881-1932, catalogue raisonné tome I, Canterbury, UK, 1992, p. 173, ISBN 0-9518533-0-9

- Pagé, Suzanne, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris: La collection, Paris Musées, 2009, pp. 372–373, ISBN 978-2-879008-88-2

- Gleizes-Metzinger, Du cubisme et après, Musée de la Poste, 2012; Musée de Lodève, 2012; Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2012, pp. 35, 43-47, ISBN 978-2-84056-368-6

- Der Sturm-Zentrum der Avant-Garde, Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, 2012, p. 189, ISBN 978-3-89202-081-3

References

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, L'Oiseau bleu, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- ↑ Joann Moser, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Cubist Works, 1910–1921, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press. p. 43.

- ↑ The Ibis in myth, science and palaeontology, by David Bressan, 2011

- ↑ Georges Cuvier, 1831, A discourse on the revolutions of the surface of the globe, and the changes thereby produced in the animal kingdom and Full text here (translated from French, Le Règne Animal'...', the first edition of which appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817. In 1826 Cuvier would publish a revised version under the name Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe)

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, Nude, 1910

- ↑ Edward F. Fry, Cubism, Oxford University Press, 1978

- ↑ Laurette E. McCarthy, Walter Pach (1883–1958), The Armory Show and the Untold Story of Modern Art in America, Penn States University Press, 2012

- ↑ Archive of American Art Picasso's handwritten list of artists recommended for the Armory Show

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, Portrait of an American Smoking (Man with a Pipe), 1911-12, oil on canvas, 92.7 x 65.4 cm (36.5 x 25.75 in) Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin

- ↑ American Studies at the University of Virginia Marketing Modern Art in America: From the Armory Show to the Department Store

- 1 2 3 Laurette E. McCarthy, Walter Pach (1883–1958). The Armory Show and the Untold Story of Modern Art in America, Penn State Press, 2011

- ↑ Gelett Burgess, Wild Men of Paris, The Architectural Record, May 1910 (New York), documents p. 3

- ↑ Third Exhibition of Contemporary French Art, Carstairs (Carroll) Gallery, New York, 8 March - 3 April, 1915. Metzinger exhibited five works: At the Velodrome (33), A Cyclist (34), Woman Smoking (35), Landscape (36), Head of a Young Girl (37), The Yellow Plume (38)

- ↑ The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Jean Metzinger

- ↑ American Archives of American Art, Montross Gallery exhibition, New York, Jean Crotti papers, 1913-1973, bulk 1913-1961

- ↑ Montross Gallery exhibition catalogue, New York

- ↑ The Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., Maurice Metzinger

- ↑ Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Histoire & Mesure, no. XXII -1 (2007), Guerre et statistiques, L'art de la mesure, Le Salon d'Automne (1903-1914), l'avant-garde, ses étranger et la nation française (The Art of Measure: The Salon d'Automne Exhibition (1903-1914), the Avant-Garde, its Foreigners and the French Nation), electronic distribution Caim for Éditions de l'EHESS (in French)

- ↑ Roger de La Fresnaye, The Conquest of the Air, 1913, 235.9 x 195.6 cm, depicting a French flag, Museum of Modern Art, New York

- ↑ Échos artistiques de la conquête de l’air : Roger de la Fresnay et la modernité

- ↑ Eric Hild-Ziem, MoMA, From Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ↑ Gino Severini, Train of the Wounded, 1913, includes the French flag

- ↑ Degenerate Art Database (Beschlagnahme Inventar, Entartete Kunst)

- 1 2 Jean Metzinger, ca. 1907, quoted in Georges Desvallières, La Grande Revue, vol. 124, 1907, as cited in Robert L. Herbert, 1968, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

- 1 2 Robert L. Herbert, 1968, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

- ↑ Joann Moser, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Pre-Cubist Works, 1904-1909, University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, p. 34

- ↑ Daniel Robbins, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, pp. 9-23

- ↑ Gleizes, Albert, Painting and its laws, (with Gino Severini: From Cubism to Classicism), translation, introduction and notes by Peter Brooke, London, Francis Boutle publishers, 2001, ISBN 1-903427-05-3. Originally published in 1923-24. The key text in which Gleizes formulated the technique of 'translation' and 'rotation' as the permanent acquisition of Cubism.

- ↑ Peter Brooke, Translator's Introduction, Albert Gleizes in 1934, discussion of Painting and Its Laws

- ↑ Metzinger's Etude pour L'Oiseau Bleu, 37 x 29,5 cm (Centre Pompidou, National museum of modern art, Paris) does not have the background architecture that Gleizes would write about in 1922

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, Etude pour L'Oiseau Bleu, 37 x 29,5 cm, Centre Pompidou, National museum of modern art, Paris

- 1 2 Mark Antliff, Patricia Dee Leighten, Cubism and Culture, Thames & Hudson, 2001

- ↑ Alexandre Thibault, La durée picturale chez les cubistes et futuristes comme conception du monde: Suggestion d'une parenté avec le problème de la temporalité en philosophie, Université Laval, 2006

- ↑ Timothy J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, ISBN 0-300-08910-4, 1999, 2001

- 1 2 3 4 Laura Kathleen Valeri, Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art, Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson, The University of Texas at Austin, 2011

- ↑ Edward F. Fry, Cubism, New York and Toronto: McGraw-Hill, 1966. See too Edward F. Fry, Cubism, Oxford University Press, 1978

- ↑ Antliff, Mark. “Bergson and Cubism: A Reassessment.” Art Journal 47, no. 4 (Winter 1988): 341-349.

- 1 2 3 4 Maurice Maeterlinck, The Blue Bird, A Fairy Play in Six Acts, 1908, translate by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos in 1910 (Full text)

- ↑ Jean Metzinger, Kubistická Technika (1913), in Antliff and Leighten, eds., A Cubism Reader, 607

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire, La Tzigane. A poem written by Apollinaire in 1907 mentions a blue bird

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire, Fiançailles, 1908

- ↑ Guillaume Apollinaire, Calligrammes, Un oiseau chante (A bird is singing), From The Self-Dismembered Man, Selected Later Poems of Guillaume Apollinaire, Donald Revell, Translator, Wesleyan University Press

- ↑ The Blue Bird, silent film, 1910

- ↑ The original Broadway production of "The Blue Bird

- ↑ Brillarelli, Livia (1995). Cecchetti, A Ballet Dynasty, Toronto: Dance Collection, Danse Educational Publications. p. 31.

- ↑ Griffiths, Paul, Igor Stravinsky, The Rake's Progress, Cambridge University Press, 1982

- ↑ Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: Stravinsky and the Russian traditions: a biography of the works through Mavra, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 1996, and Albert Gleizes

- ↑ Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: Stravinsky and the Russian traditions: a biography of the works through Mavra, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 1996, and Chaikovsky (Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky)

- ↑ Albert Gleizes, Le Cubisme et la Tradition, Montjoie, Paris, 10 February 1913, p. 4. Reprinted in Tradition et Cubisme, Paris, 1927

- ↑ Albert Gleizes, Portrait of Igor Stravinsky, 1914, Oil on canvas, 51 x 45" (129.5 x 114.3 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- ↑ Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky, Igor Stravinsky, Pas de deux (L'oiseau bleu - Bluebird) from P. Tchaikovsky's ballet, The sleeping beauty, B.Schott's Söhne, 1953

- ↑ Igor Stravinsky, Pëtr I. Čajkovskij, Pas-de-deux: L' oiseau bleu - Bluebird, from P. Tschaikowsky's ballet "The sleeping Beauty", arranged for small orchestra. Miniature score, Schott, 1953

- ↑ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 858, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- 1 2 3 Madame d'Aulnoy, L’Oiseau bleu, 1697, full text in French

- 1 2 3 Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, p. 22

- ↑ Société des artistes indépendants. 29, Catalogue de la 29e exposition, 1913 : Quai d'Orsay, Pont de l'Alma, du 19 mars au 18 mai inclus / Société des artistes indépendants

- ↑ Société des artistes indépendants. 29, Catalogue de la 29e exposition, 1913, Gleizes

- ↑ Société des artistes indépendants. 29, Catalogue de la 29e exposition, 1913, Delaunay

- ↑ Salon des Indépendants 1913

- ↑ Herwarth Walden, Erster deutscher Herbstsalon, Berlin 1913

- ↑ Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon, Berlin, 1913, list of artists and works displayed

- ↑ Orphism, Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon, MoMA, Hajo Düchting, From Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ↑ Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, list of donations and acquisitions

- ↑ Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

- ↑ Kubistische werken op de Maîtres de l'art indépendant (in Dutch)

- ↑ Waterhouse & Dodd Fine Art

- ↑ Parijs 1937 L'art indépendant (in Dutch)

- ↑ Postage stamp: Jean Metzinger L'oiseau bleu (1912-1913)

- ↑ Postage stamp: Albert Gleizes Le chant de guerre, portrait de Florent Schmitt (1915)

- ↑ Cubism represented on 12 stamps, published in 2012

- ↑ Logo's for La Poste, 1900-2011

- ↑ Philatélie : un carnet pour le cubisme à l’Espace et au Carré, L'oiseau bleu postage stamp

- ↑ Bohr, N. (1913). "On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine Series 6. London. 26: 1–25. doi:10.1080/14786441308634955. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- ↑ Bohr, N. (1913). "Part II - Systems containing only a Single Nucleus" (PDF). Philosophical Magazine. 26: 476–502. doi:10.1080/14786441308634993. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- ↑ "Niels Bohr: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922". Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1922–1941. Elsevier. 1966. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ Sagnac, Georges (1913). "The demonstration of the luminiferous aether by an interferometer in uniform rotation". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences. 157: 708–710.

- ↑ Sagnac, Georges (1913). "On the proof of the reality of the luminiferous aether by the experiment with a rotating interferometer". Comptes rendus. 157: 1410–1413.

- ↑ Quintin, M. (1996). "Qui a découvert la fluorescence X ?". Journal de Physique IV. 6 (4). Retrieved 2012-06-21.

- ↑ Web page titled "Guillaume Apollinaire (1880 - 1918)" at the Poetry Foundation website, retrieved August 9, 2009. Archived 2009-09-03.

- ↑ Web page titled "POET Francis Jammes (1868 - 1938)", at The Poetry Foundation website, retrieved August 30, 2009

External links

- Jean Metzinger: Divisionism, Cubism, Neoclassicism and Post Cubism

- Culture.gouv.fr, le site du Ministère de la culture - base Mémoire

- Culture.gouv.fr, Base Mémoire, La Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine, pages 1–50 of 144

- Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

- The Blue Bird for Children, 1913, by Georgette Leblanc [Madame Maurice Maeterlinck. Edited and arranged for schools, translated by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos, Silver, Burdett & Company, 1913 (Full text, illustrated)