Curly Howard

| Curly Howard | |

|---|---|

|

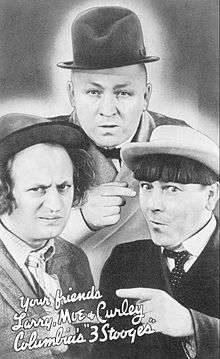

Curly Howard in Disorder in the Court | |

| Born |

Jerome Lester Horwitz October 22, 1903 Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

January 18, 1952 (aged 48) San Gabriel, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Cerebral hemorrhage |

| Other names | Jerry Howard |

| Occupation | Actor, comedian |

| Years active | 1918–1947 |

| Height | 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) |

| Spouse(s) |

Julia Rosenthal (1930–1931; annulled) Elaine Ackerman (1937–1940; divorced) Marion Buxbaum (1945–1946; divorced) Valerie Newman (1947–1952; his death) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives |

Moe Howard (brother) Shemp Howard (brother) |

| Website | threestooges.net |

Jerome Lester Horwitz (October 22, 1903 – January 18, 1952), better known by his stage name Curly Howard, was an American comedian and vaudevillian actor. He was best known as the most outrageous and energetic member of the American farce comedy team the Three Stooges, which also featured his older brothers Moe and Shemp Howard and actor Larry Fine. Curly was generally considered the most popular and recognizable of the Stooges.[1] He was well known for his high-pitched voice and vocal expressions ("nyuk-nyuk-nyuk!", "woob-woob-woob!", "soitenly![2]" (certainly), and barking like a dog) as well as his physical comedy (e.g., falling on ground and pivoting on his shoulder as he "walked" in circular motion), improvisations, and athleticism.[3] An untrained actor, Curly borrowed (and significantly exaggerated) the "woob woob" from "nervous" and soft-spoken comedian Hugh Herbert.[4] Curly's unique version of "woob-woob-woob" was firmly established by the time of the Stooges' second Columbia film, Punch Drunks (1934).[3]

Curly was forced to leave the Three Stooges act in 1946 when a massive stroke ended his showbusiness career. He suffered through serious health problems and several more strokes until his death in 1952 at age 48.

Early life

Curly Howard was born Jerome Lester Horwitz in the Bensonhurst section of the Brooklyn borough of New York City. Of Lithuanian Jewish ancestry, he was the fifth of the five Horwitz brothers. Because he was the youngest, his brothers called him "Babe" to tease him. The name "Babe" stuck with him all his life, although when his older brother Shemp Howard married Gertrude Frank, who was also nicknamed "Babe," the brothers called him "Curly" to avoid confusion.[5] His full formal Hebrew name was "Yehudah Lev ben Shlomo Natan ha Levi."[6]

A quiet child, Curly rarely caused problems for his parents (something older brothers Moe and Shemp excelled in). He was a mediocre student but excelled as an athlete on the school basketball team. He didn't graduate from high school but kept himself busy with odd jobs and constantly followed his older brothers, whom he idolized. He was also an accomplished ballroom dancer and singer and regularly turned up at the Triangle Ballroom in Brooklyn, occasionally bumping into George Raft.[3]

When Curly was 12, he accidentally shot himself in the left ankle while cleaning a rifle. Moe rushed him to the hospital and saved his life. The wound resulted in a noticeably thinner left leg and a slight limp. He was so frightened of surgery that he never had the limp corrected. While with the Stooges, he developed his famous exaggerated walk to mask the limp on screen.[3]

Curly was interested in music and comedy and would watch his brothers Shemp and Moe perform as stooges in Ted Healy's vaudeville act. He also liked to hang around backstage, although he never participated in any of the routines.

Career

Early career and the Three Stooges

From an early age, Curly was always "in demand socially," as brother Moe put it.[3] He married his first wife, Julia Rosenthal, on August 5, 1930, but the couple had their marriage annulled shortly afterwards.[7]

Curly's first on-stage break was as a comedy musical conductor in 1928 for the Orville Knapp Band. Moe later recalled that his performances usually overshadowed those of the band.[3] Though Curly enjoyed the gig, he watched as older brothers Moe and Shemp (and partner Larry Fine) made it big as some of Ted Healy's "stooges." Vaudeville star Healy had a very popular stage act, in which he would try to tell jokes or sing, only to have his stooges wander on stage and interrupt or heckle him and cause disturbances from the audience. Meanwhile, Healy and company appeared in their first feature film, Rube Goldberg's Soup to Nuts (1930).[1]

Shemp, however, disliked Healy's abrasiveness, bad temper, and heavy drinking.[3] In 1932, he was offered a contract at the Vitaphone Studios in Brooklyn. (Contrary to stories told by Moe, the role of "Knobby Walsh" in the Joe Palooka series did not come along until late 1935, after Shemp had been at Vitaphone for three years and had already appeared in almost thirty short subjects.) Shemp was thrilled to be away from Healy but, as was his nature, worried incessantly about brother Moe and partner Larry. Moe, however, told Shemp to pursue this opportunity.

With Shemp gone, Moe suggested that Curly fill the role of the third stooge. But Healy felt that Curly, with his thick, chestnut hair and elegant waxed mustache, did not "look funny". Curly left the room and returned minutes later with his head shaven (the mustache remained very briefly). Healy quipped, "Boy, don't you look girlie?" Moe misheard the joke as "curly," and all who witnessed the exchange realized that the nickname "Curly" would be a perfect fit. In one of the few interviews Curly gave in his lifetime, he complained about the loss of his hair: "I had to shave it off right down to the skin."[3] In 1934, MGM was building Healy up as a solo comedian in feature films and Healy dissolved the act to pursue his own career. Like Shemp, the team of Howard, Fine, and Howard was tired of Healy's alcoholism and abrasiveness and renamed their act the "Three Stooges." That same year, they signed on to appear in two-reel comedy short subjects for Columbia Pictures. The Stooges soon became the most popular short-subject attraction, with Curly playing an integral part in the trio's work.[3]

Prime years

Curly's childlike mannerisms and natural comedic charm made him a hit with audiences, particularly children. He was known in the act for having an "indestructible" head, which always won out by breaking anything that assaulted it, including saws (resulting in his characteristic quip, "Oh, look!"). Although having no formal acting training, his comedic skills were exceptional. Many times, directors would simply let the camera roll freely and let Curly improvise. Jules White, in particular, would leave gaps in the Stooge scripts where Curly could improvise for several minutes.[3] In later years, White commented: "If we wrote a scene and needed a little something extra, I'd say to Curly, 'Look, we've got a gap to fill this in with a "woob-woob" or some other bit of business.' And he never disappointed us."[4]

By the time the Stooges hit their peak in the late 1930s, their films had almost become vehicles for Curly's unbridled comic performances. Classics like A Plumbing We Will Go (1940), We Want Our Mummy (1938), An Ache in Every Stake (1941), and Cactus Makes Perfect (1942) display his ability to take inanimate objects (like food, tools, pipes, etc.) and turn them into ingenious comic props.[3] Moe later confirmed that when Curly forgot his lines, that merely allowed him to improvise on the spot so that the "take" could continue uninterrupted:

| “ | If we were going through a scene and he'd forget his words for a moment, you know, rather than stand, get pale and stop, you never knew what he was going to do. On one occasion he'd get down to the floor and spin around like a top until he remembered what he had to say.[8] | ” |

Curly also developed a set of reactions and expressions that the other Stooges would imitate long after he'd left the act:

- "Nyuk, nyuk, nyuk" - Curly's traditional laughter, accompanied by manic finger-snapping, often used to amuse himself;

- "Woo, woo, woo!" - used when he was either scared, dazed, or flirting with a "dame";

- "Hmmm!" - an under-the-breath, high-pitched sound meant to show different emotions, including interest, excitement, frustration, or anger; one of his most-used reactions/expressions;

- "Nyahh-ahhh-ahhh!" - scared reaction (this was the reaction most often used by the other Stooges after Curly's departure);

- "Laaa-Deeeeeee" or simply "Laaa, laaa, laaa" - Curly's working "song"; also used when he was acting innocently right before taking out an enemy;

- "Ruff Ruff" - dog bark, used to give an enemy a final push before departing the scene, or barking at an attractive dame;

- "Ha-cha-cha-cha-cha!" - a take on Jimmy Durante's famed call, used more sparingly than other expressions;

- "I'm a victim of soicumstance [circumstance]";

- "Soitenly!" ("certainly");[9]

- "I'll moider you!" ("I'll murder you!"; used as a threat, but much more by Moe than by Curly);

- "Huff huff huff!" - sharp, huffing exhales either due to excitement or meant to provoke a foe;

- "Ah-ba-ba-ba-ba-ba-ba!" - used during his later years, a sort of nonsense, high-pitched yelling that signified being scared or overly excited;

- "Indubitably" - an expression used to feign an intelligent response;

- "Hee Beee Beee Beee Beee Beee" - scared or embarrassed reaction;

- "A WISE Guy, Eh?" - annoyed response;

- "Oh Look!" - surprised remark, usually about a common object;

- "Say a few syllables" - to another (injured) stooge, usually Moe.

On several occasions, Moe was convinced that rising star Lou Costello (a close friend of Shemp) was stealing material from Curly.[5] Costello was known to acquire prints of the Stooges' films from Columbia Pictures on occasion, presumably to study Curly. Inevitably, Curly's routines would show up in Abbott and Costello feature films, much to Moe's chagrin.[5] (It did not help that Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn would not allow the Stooges to make feature-length films like contemporaries Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, and Abbott and Costello.[10])

Illness

Slow decline

By 1944, Curly's energy began to wane. Films like Idle Roomers (1944) and Booby Dupes (1945) present a Curly whose voice was deeper and his actions slower. It is believed that he suffered the first of many strokes between the filming of Idiots Deluxe (October 1944) and If a Body Meets a Body (March 1945). After the filming of the feature length Rockin' in the Rockies (December 1944), he finally checked himself (at Moe's insistence) into Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara, California, on January 23, 1945, and was diagnosed with extreme hypertension, a retinal hemorrhage, and obesity. His ill health forced him to rest, leading to only five shorts being released in 1945 (the normal output was six to eight per year).

The Three Stooges: An Illustrated History, From Amalgamated Morons to American Icons by Michael Fleming, unfortunately invented an untrue tale about Moe pleading with Harry Cohn to allow his younger brother some time off upon discharge to regain his strength, but Cohn would not halt the production of his profitable Stooge shorts and flatly refused his request (one of the worst criticisms leveled at Cohn in his last years). Author Michael Fleming: "it was a disastrous course of action."[1] In truth, the Stooges had five months off between August 1945 and January 1946. They used that time to book themselves a feature film at Monogram, and then leave on a 2-month live performance commitment in New York City working shows 7 days per week. During that grueling NYC appearance, Curly met and married his 3rd wife Marion Buxbaum, a bad relationship that further deteriorated Curly's health and morale. Returning to L.A. in late November 1945, Curly was a shell of his former self. With two months rest, the team's 1946 schedule at Columbia commenced in late January, but involved only 24 days work during February - early May. In spite of 8 weeks' time off in that same period, Curly's condition continued to deteriorate.

By early 1946, Curly's voice had become even more coarse than before, and it was increasingly difficult for him to remember even the simplest dialogue. He had lost a considerable amount of weight, and lines had creased his face.

1946 stroke

Half-Wits Holiday (released 1947) would be Curly's final appearance as an official member of the Stooges. During filming on May 6, 1946, Curly suffered a severe stroke while sitting in director Jules White's chair, waiting to film the last scene of the day. When Curly was called by the assistant director to take the stage, he did not answer. Moe went looking for his brother: he found Curly with his head dropped to his chest. Moe later recalled that his mouth was distorted and he was unable to speak, only cry. Moe quietly alerted White to all this, leading the latter to rework the scene quickly, dividing the action between Moe and Larry while Curly was rushed to the hospital,[11] where Moe joined him after the filming. Curly spent several weeks at the Motion Picture and Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, California before returning home for further recuperation.

In January 1945, Shemp had been recruited to substitute for a resting Curly during live performances in New Orleans.[12] After Curly's stroke, Shemp agreed to replace him in the Columbia shorts, but only until his younger brother was well enough to rejoin the act. An extant copy of the Stooges' 1947 Columbia Pictures contract was signed by all four Stooges and stipulated that Shemp's joining "in place and stead of Jerry Howard" would be only temporary until Curly recovered sufficiently to return to work full time.

Curly, partially recovered and with his hair regrown, made a brief cameo appearance as a train passenger barking in his sleep in the third film after brother Shemp's return, Hold That Lion! (1947). It was the only film that featured Larry Fine and all three Howard brothers—Moe, Shemp and Curly—simultaneously; director White later said he spontaneously staged the bit during Curly's impromptu visit to the soundstage:

| “ | It was a spur-of-the-moment idea. Curly was visiting the set; this was sometime after his stroke. Apparently he came in on his own, since I didn't see a nurse with him. He was sitting around, reading a newspaper. As I walked in, the newspaper he had in front of his face came down and he waved hello to me. I thought it would be funny to have him do a bit in the picture and he was happy to do it.[11] | ” |

Curly filmed a second cameo as an irate chef two years later for the short Malice in the Palace (1949), but due to his illness, his performance was not deemed good enough and his scenes were cut. A lobby card for the short shows him with the other Stooges, although he never appeared in the final release.

Retirement

Still not fully recovered from his stroke, Curly met Valerie Newman and married her on July 31, 1947. A friend, Irma Leveton, later recalled, "Valerie was the only decent thing that happened to Curly and the only one that really cared about him."[3] Although his health continued to decline after the marriage, Valerie gave birth to a daughter, Janie, in 1948.[8]

Later that year Curly suffered a second massive stroke, which left him partially paralyzed. He used a wheelchair by 1950 and was fed boiled rice and apples as part of his diet to reduce his weight (and blood pressure). Valerie admitted him into the Motion Picture Country House and Hospital on August 29, 1950. He was released after several months of treatment and medical tests, although he would return periodically until his death.[3]

In February 1951, he was placed in a nursing home, where he suffered another stroke a month later. In April, he went to live at the North Hollywood Hospital and Sanitarium.[3]

Final months and death

In December 1951, the North Hollywood Hospital and Sanitarium supervisor advised the Howard family that Curly was becoming a problem to the nursing staff at the facility because of his mental deterioration. They admitted they could no longer care for him and suggested he be placed in a mental hospital. Moe refused and relocated him to the Baldy View Sanitarium in San Gabriel, California.[3]

On January 7, 1952, Moe was contacted on the Columbia set while filming He Cooked His Goose to help move Curly for what would be the last time. Eleven days later, on January 18, Curly died at 48.[13] He was given a Jewish funeral and laid to rest at Home of Peace Cemetery in East Los Angeles.[3]

Personal life

Curly's offscreen personality was the antithesis of his onscreen manic persona. An introvert, he generally kept to himself, rarely socializing with people unless he had been drinking (which he would increasingly turn to as the stresses of his career grew). In addition, he came to life when in the presence of brother Shemp. Curly could not be himself around brother Moe, who treated his younger brother with a fatherly wag of the finger. Never an intellectual, Curly simply refrained from engaging in "crazy antics" unless he was in his element: with family, performing or intoxicated.[3]

On June 7, 1937, Curly married Elaine Ackerman, who gave birth to their only child, Marilyn, the following year. The couple divorced in 1940, after which he gained a lot of weight and developed hypertension. He was also insecure about his shaved head, believing it made him unappealing to women; he increasingly drank to excess and caroused to cope with his feelings of inferiority. He took to wearing a hat in public to convey an image of masculinity, saying he felt like a little kid with his hair shaved off, even though he was popular with women all his life.[1] In fact, many who knew him said women were his main weakness. Moe's son-in-law Norman Maurer even went so far as to say he "was a pushover for women. If a pretty girl went up to him and gave him a spiel, Curly would marry them. Then she would take his money and run off. It was the same when a real estate agent would come up and say 'I have a house for you'; Curly would sell his current home and buy another one."[3]

During World War II, for seven months of each year, the trio's filming schedule would go on hiatus, allowing them to make personal appearances. The Stooges entertained servicemen constantly, and the intense work schedule took its toll on Curly. He never drank while performing in film or on stage; Moe would not allow it. But once away from Moe's watchful eye, he would find the nearest nightclub, down a few drinks, and enjoy himself. His drinking, eating, and carousing increased. He had difficulties managing his finances, often spending his money on wine, food, women, homes, cars, and especially dogs, and was often near poverty. Moe eventually helped him manage his money and even filled out his income tax returns.[3]

Curly found constant companionship in his dogs and often befriended strays whenever the Stooges were traveling. He would pick up homeless dogs and take them with him from town to town until he found them a home somewhere else on the tour.[1] When not performing, he would usually have a few dogs waiting for him at home as well.[14]

Moe urged Curly to find himself a wife, hoping it would persuade his brother to finally settle down and allow his health to improve somewhat. After a two-week courtship, he married Marion Buxbaum on October 17, 1945, a union which lasted approximately three months. The divorce proceeding was a bitter one, exacerbated by exploitation in the local media. After the divorce, his health fell into rapid and devastating decline.[3]

Legacy

Curly Howard is considered by many fans and critics alike to be their favorite member of The Three Stooges.[1] In a 1972 interview Larry Fine recalled, "Personally, I thought Curly was the greatest because he was a natural comedian who had no formal training. Whatever he did, he made up on the spur of the moment. When we lost Curly, we took a hit."[15] Curly's mannerisms, behavior and personality along with his catchphrases of "n'yuk, n'yuk, n'yuk," "woob, woob, woob" and "soitenly!" have become a part of American popular culture. Steve Allen called him one of the "most original, yet seldom recognized, comic geniuses."[14]

The Ted Okuda and Edward Watz book The Columbia Comedy Shorts puts Curly's appeal and legacy in critical perspective:

| “ | Few comics have come close to equaling the pure energy and genuine sense of fun Curly was able to project. He was merriment personified, a creature of frantic action whose only concern was to satisfy his immediate cravings. Allowing his emotions to dominate, and making no attempt whatsoever to hide his true feelings, he would chuckle self-indulgently at his own cleverness. When confronted with a problem he would grunt, slap his face and tackle the obstacle with all the tenacity of a six-year-old child.[4] | ” |

From 1980 to 1982, the ABC TV comedic skit series, Fridays, featured an occasional skit of "The Numb Boys" - essentially a Three Stooges routine related to a recent news topic - with John Roarke playing a very convincing Curly (and Bruce Mahler as Moe and Larry David as Larry).[16]

In 2000, longtime Stooges fan Mel Gibson produced a television film for ABC about the life and careers of the Stooges. In an interview promoting the film, he said Curly was his favorite of the Stooges.[17] In the film, Curly was played by Michael Chiklis.

In the 2012 Farrelly brothers' film The Three Stooges, Will Sasso portrays Curly. Robert Capron portrays Young Curly.

Filmography

Features

- Turn Back the Clock (1933)

- Broadway to Hollywood (1933)

- Meet the Baron (1933)

- Dancing Lady (1933)

- Myrt and Marge (1933)

- Fugitive Lovers (1934)

- Hollywood Party (1934)

- The Captain Hates the Sea (1934)

- Start Cheering (1938)

- Time Out for Rhythm (1941)

- My Sister Eileen (1942)

- Good Luck, Mr. Yates (1943) (scenes deleted, reused in Gents Without Cents)

- Rockin' in the Rockies (1945)

- Swing Parade of 1946 (1946)

- Stop! Look! and Laugh! (1960) (scenes from Stooge shorts)

Short subjects

- Nertsery Rhymes (1933)

- Beer and Pretzels (1933)

- Hello Pop! (1933)

- Plane Nuts (1933)

- Roast Beef and Movies (1934)

- Jail Birds of Paradise (1934)

- Hollywood on Parade # B-9 (1934)

- Woman Haters (1934) (*credited as "Curley")

- The Big Idea (1934)

- Punch Drunks (1934)

- Men in Black (1934)

- Three Little Pigskins (1934)

- Horses' Collars (1935)

- Restless Knights (1935)

- Screen Snapshots Series 14, No. 6 (1935)

- Pop Goes the Easel (1935)

- Uncivil Warriors (1935)

- Pardon My Scotch (1935)

- Hoi Polloi (1935)

- Three Little Beers (1935)

- Ants in the Pantry (1936)

- Movie Maniacs (1936)

- Screen Snapshots Series 15, No. 7 (1936)

- Half Shot Shooters (1936)

- Disorder in the Court (1936)

- A Pain in the Pullman (1936)

- False Alarms (1936)

- Whoops, I'm an Indian! (1936)

- Slippery Silks (1936)

- Grips, Grunts and Groans (1937)

- Dizzy Doctors (1937)

- Three Dumb Clucks (1937)

- Back to the Woods (1937)

- Goofs and Saddles (1937)

- Cash and Carry (1937)

- Playing the Ponies (1937)

- The Sitter Downers (1937)

- Termites of 1938 (1938)

- Wee Wee Monsieur (1938)

- Tassels in the Air (1938)

- Healthy, Wealthy and Dumb (1938)

- Violent Is the Word for Curly (1938)

- Three Missing Links (1938)

- Mutts to You (1938)

- Flat Foot Stooges (1938)

- Three Little Sew and Sews (1939)

- We Want Our Mummy (1939)

- A Ducking They Did Go (1939)

- Screen Snapshots: Stars on Horseback (1939)

- Yes, We Have No Bonanza (1939)

- Saved by the Belle (1939)

- Calling All Curs (1939)

- Oily to Bed, Oily to Rise (1939)

- Three Sappy People (1939)

- You Nazty Spy! (1940)

- Screen Snapshots: Art and Artists (1940)

- Rockin' thru the Rockies (1940)

- A Plumbing We Will Go (1940)

- Nutty but Nice (1940)

- How High Is Up? (1940)

- From Nurse to Worse (1940)

- No Census, No Feeling (1940)

- Cookoo Cavaliers (1940)

- Boobs in Arms (1940)

- So Long Mr. Chumps (1941)

- Dutiful but Dumb (1941)

- All the World's a Stooge (1941)

- I'll Never Heil Again (1941)

- An Ache in Every Stake (1941)

- In the Sweet Pie and Pie (1941)

- Some More of Samoa (1941)

- Loco Boy Makes Good (1942)

- What's the Matador? (1942)

- Cactus Makes Perfect (1942)

- Matri-Phony (1942)

- Three Smart Saps (1942)

- Even as IOU (1942)

- Sock-a-Bye Baby (1942)

- They Stooge to Conga (1943)

- Dizzy Detectives (1943)

- Spook Louder (1943)

- Back from the Front (1943)

- Three Little Twirps (1943)

- Higher Than a Kite (1943)

- I Can Hardly Wait (1943)

- Dizzy Pilots (1943)

- Phony Express (1943)

- A Gem of a Jam (1943)

- Crash Goes the Hash (1944)

- Busy Buddies (1944)

- The Yoke's on Me (1944)

- Idle Roomers (1944)

- Gents Without Cents (1944)

- No Dough Boys (1944)

- Three Pests in a Mess (1945)

- Booby Dupes (1945)

- Idiots Deluxe (1945)

- If a Body Meets a Body (1945)

- Micro-Phonies (1945)

- Beer Barrel Polecats (1946)

- A Bird in the Head (1946)

- Uncivil War Birds (1946)

- The Three Troubledoers (1946)

- Monkey Businessmen (1946)

- Three Loan Wolves (1946)

- G.I. Wanna Home (1946)

- Rhythm and Weep (1946)

- Three Little Pirates (1946)

- Half-Wits Holiday (1947)

- Hold That Lion! (1947, cameo appearance)

- Malice in the Palace (1949, cameo appearance filmed but not used)

- Booty and the Beast (1953, recycled footage from Hold That Lion!)

Further reading

- Curly: An Illustrated Biography of the Superstooge by Joan Howard Maurer (Citadel Press, 1988).

- The Complete Three Stooges: The Official Filmography and Three Stooges Companion by Jon Solomon, (Comedy III Productions, Inc., 2002).

- One Fine Stooge: A Frizzy Life in Pictures by Steve Cox and Jim Terry, (Cumberland House Publishing, 2006).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fleming, Michael (2002) [1999]. The Three Stooges: An Illustrated History, From Amalgamated Morons to American Icons. New York: Broadway Books. pp. 22, 21, 23, 25, 33, 49, 50. ISBN 0-7679-0556-3.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhgWKUz0Q1U

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Maurer, Joan Howard; Jeff Lenburg; Greg Lenburg (1982). The Three Stooges Scrapbook. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-0946-5.

- 1 2 3 Okuda, Ted; Watz, Edward (1986). The Columbia Comedy Shorts. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 63. ISBN 0-89950-181-8.

- 1 2 3 Howard, Moe; Joan Howard Maurer (1977). Moe Howard and the Three Stooges. Citadel Press. pp. 21–23, 25, 33, 49–50.

- ↑ Curly has a traditional Jewish gravestone with his full formal Hebrew name engraved on it in Hebrew script, directly transliterated from the Hebrew inscription contained there.

- ↑ The Three Stooges Journal, Winter 2005; Issue #76, p. 4

- 1 2 A&E Network's Biography

- ↑ Seely, Peter; Gail W. Pieper (2007). Stoogeology: Essays on the Three Stooges. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 9. ISBN 0786429208.

- ↑ willdogs

- 1 2 Okuda, Ted; Watz, Edward; (1986). The Columbia Comedy Shorts, p. 69, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-89950-181-8

- ↑ "Moe and Shemp Howard and Larry Fine, who were the originals in the Three Stooges act, compose the trio to appear here. Curley [sic] Howard, who took Shemp's place after the act had been organized some years and whose appearance is familiar to movie audiences, is not on the current tour because of illness." The Times-Picayune; January 18, 1946 edition

- ↑ "http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=511"

- 1 2 The Making of the Stooges VHS Documentary, narrated by Steve Allen (1984)

- ↑ The Three Stooges Story, (2001).

- ↑ List of Fridays episodes.

- ↑ TV Guide.com.

External links

- Curly Howard at The Three Stooges Official Website

- Curly Howard at the Internet Movie Database

- Curly Howard at the Internet Broadway Database

- "Curly Howard". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- Three Stooges Sued by Curly's Widow