Venustiano Carranza, Mexico City

| Venustiano Carranza | |

|---|---|

| Delegación | |

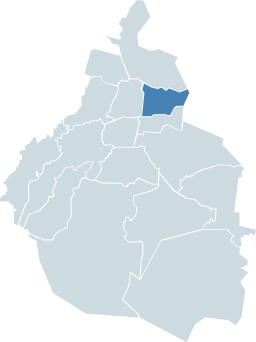

Venustiano Carranza within the Federal District | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Federal entity | D.F. |

| Established | 1970 |

| Named for | Venustiano Carranza |

| Seat | Colonia Jardín Balbuena |

| Government | |

| • Jefe delegacional | Israel Moreno Rivera (PRD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 33.42 km2 (12.90 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 430,978 |

| • Density | 13,000/km2 (33,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | Central Standard Time (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | Central Daylight Time (UTC-5) |

| Postal codes | 15000 – 15990 |

| Website | http://www.vcarranza.df.gob.mx/ |

Venustiano Carranza is one of the 16 municipalities of Mexico City. The borough was formed in 1970 when the center of Mexico City was subdivided into four boroughs. Venustiano Carranza extends from the far eastern portion of the historic center of Mexico City eastward to the Peñón de los Baños and the border dividing the then Federal District from the State of Mexico. Historically, most of the territory was under Lake Texcoco, but over the colonial period into the 20th century, the lake dried up and today the area is completely urbanized. The borough is home to three of Mexico City's major traditional markets, including La Merced, the National Archives of Mexico, the Palacio Legislativo de San Lázaro, the TAPO intercity bus terminal and the Mexico City Airport.

Geography and environment

The borough is located in the center-east of Mexico City. It borders Gustavo A. Madero, Cuauhtémoc and Iztacalco with the State of Mexico to the east. The territory measures 33.42 km2 (13 sq mi) which is 2.24% of the total of Mexico City. The borough has 2,290 blocks and eighty officially designated neighborhoods.[1]

It has an average altitude of 2,240 m (7,349 ft) above sea level with most of the surface flat. The territory is mostly the bed of the former Lake Texcoco with soils of compressed clay over sand, with the exception of the Peñón de los Baños at 2,290 metres (7,513 ft) above sea level, made of basalt .[1][2] Because it is mostly former lakebed, flooding (especially during the rainy season from June to October) and hailstorms in winter, are not uncommon. Flooding is often caused or exacerbated by the deteriorated drainage system.[3] Aside from the one elevation, the far west of the borough corresponds to the far east of the former Tenochtitlan island. For this reason, about one quarter of the historic center of Mexico City belongs to the borough.[4] It has a semi dry, temperate climate with an average annual temperature of 16 °C (61 °F) and an average rainfall of 600 mm (24 in).[1]

In the parks and other green spaces of the borough, trees such as ash, white cedar, cypress, fig and Indian laurel, various scrubs and grasses can be found. Wildlife is limited to birds, rodents, lizards and insects.[3] In 2011, reforestation efforts took place in four areas of the borough, planting 15,000 trees.[5]

Neighborhoods

One of the notable neighborhoods of the borough is Magdalena Mixhuca .[2] The community was a small island in Lake Texcoco in the pre Hispanic period and eventually became physically connected to the surrounding areas as the lake dried up.[3] However, the area is still marked by the existence of small one-story houses with look very similar often painted some shade of orange, making it look like a small town. The kiosk in the community center is also painted the same color. Next to the plaza it is on is the church of Santa María Magdalena Mixhuca with an image of Mary Magdalene inside. The name Mixhuca comes from Nahuatl and means place of childbirth. The area is dedicated to Mary Magdalene because the first-born daughter of Moctezuma II requested such from Hernán Cortés .[6]

Other notable neighborhoods include Colonia Balbuena, named after poet Bernardo de Balbuena,[3] La Candelaria de los Patos, which gets its name from the large flocks of ducks that used to live here when the area was still lake, El Parque, Jamaica, Zaragoza, Romero Rubio and Gómez Fárias.[4][7]

Landmarks

The borough is home to forty two traditional markets, with over 14,000 individual vendors.[3] This includes three of Mexico City’s large traditional markets, La Merced Market, Mercado de Sonora and Mercado Jamaica .[8][9] La Merced is historically and culturally part of the historic center of Mexico City and is the largest retail food market in the city. The main building is 400 meters long with 3,205 stands mostly selling produce and groceries, meats and fish. There is a smaller section devoted to baskets, rope and handcrafts with another building selling leather, storage containers, ornamental plants and prepared food. This market is located in an area which has been a major market and receiving area since the colonial period. The entire neighborhood was filled in informal stands until the first building was constructed in 1860. Until the mid 20th century, La Merced was the main wholesale market, but this function was moved to the new Central de Abastos market in Iztapalapa. Mercado Jamaica is located in the neighborhood of the same name, next to the metro station named after it. It is known for the sale flowers and ornamental plants, but it also sells produce, groceries, meats and a selection of handcrafts. Mercado Sonora was opened in 1957. It is best known for the section dedicated to herbal medicine and the occult such as items associated with Santa Muerte. This section in located in the back. Other items include live animals, dishes, party favors and plastic items.[9]

The National Archives or Archivo General de la Nación (formerly known as the Palacio Negro de Lecumberri) contain a significant part of Mexico’s written history.[7] Lecumberri was begun in 1885 as a prison when then San Lázaro area was at the city’s periphery. Construction took 15 years and 2.5 million pesos and was inaugurated in 1900 as the most modern prison in Latin America. The prison was the scene of the incarceration and execution of Francisco I. Madero and José María Pino Suárez in 1913. By the 1970s, the prison had as many as 5,000 prisoners in 1,000 cells. The prison was closed by the end of the decade and renovated to its current use.[10]

The Palacio Legislativo de San Lázaro was constructed on the former site of the San Lázaro Railroad Station by José López Portillo in the 1970s, opened in 1981. It was constructed to move the legislative body away from the Donceles Legislative Palace in the historic center of Mexico City. The building was nearly destroyed by a fire in 1989 but was restored in 1992. The façade is of red tezontle stone with white marble in the center with the seal of the country prominently displayed. The vestibule contains a collection of murals depicting Mexico’s history done by Adolfo Mexiac. The main chamber can seat up to 2000 spectators.[11] When the legislative building was restored, a museum called “Sentimientos de la nación” Legislative Museum was installed. This museum is dedicated to the history of Mexico’s government and history up to the present.[12]

The main governmental building for the borough is located at Avenida Francisco del Paso y Troncoso in Colonia Jardín Balbuena. These offices were opened in 1974 on the site of the former Balbuena military airfield. The building has four murals painted by Montury such as "El canto del cisne", "Quienes somos", "América en llamas" y "Dame una palanca y destruiré el mundo".[2][7]

Major churches in the area include the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos in Colonia 20 de Noviembre, Temple of La Soledad y la Santa Cruz in Colonia Merced Balbuena, the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe y La Santísima Hostia Sangrante in Colonia El Parque and the Temple of San Antonio Tomatlán in Colonia Morelos.[13] La Soledad de la Santa Cruz Church was built by Augustine monks. This church was expanded between 1750 and 1789 to three naves supported by pilasters and a new main altar was installed. To the south of this church, the Temple of San Jeronimito was constructed in the La Candelaria de los Patos neighborhood.[4]

The oldest sports facility of Mexico City was built in the Balbuena area with the name of Venustiano Carranza, inaugurated in 1929.[3][4] Other sports facilities include Centro Deportivo Moctezuma, Centro Deportivo Ramón López Velarde, Centro Deportivo Felipe "Tibio Muñoz,” Centro Deportivo Ing. Eduardo Molina, Centro deportivo José Ma. Pino Suárez, Centro Deportivo Velódromo Olímpico, Centro Deportivo Plutarco Elías Calles and Centro Deportivo Oceanía.[3]

The Centro Cultural Carranza was inaugurated in 2011 in Colonia Jardín Balbuena with the aim of making it the most important recreational and cultural center in the center east of the Federal District.[14]

In addition, the borough contains about one hundred statues, plazas, buildings and gardens which function as monuments to the history of the borough and of Mexico. These include the monument to General Carranza in front of the borough hall, a monument to Simón Bolívar in Jardín Simón Bolívar, a plaque and medallions marking the place where Francisco I. Madero and José María Pino Suárez were executed, and one to Mahatma Gandhi .[3]

Reenactment of the Battle of Puebla

The Battle of Puebla has been reenacted each year at the Peñón de los Baños since 1930. Residents of this area dress as the Mexican forces, called Zacapoaxtlas and the French army and even includes the firing of cannons with blanks for effect.[15] The reenactment is performed by hundreds of residents of three neighborhoods around Peñón de los Baños, with the event occurring in the neighborhood of that name. The divide to represent the French army and the band of peasants called Zacapoaxtlas along with Mexican soldiers which won the historical battle. The event begins early in the morning on May 5 with a salute to the Mexican flag and a parade to the Peñón de los Baños mountain. The first act occurs in Barrio del Carmen, then another act to commemorate the Treaty of Loreto and the Treaty of Guadalupe on Hidalgo and Chihualcan Streets. After this, there is a large shared banquet with food provided by area residents to the mock soldiers. Then there is an inspection of the troops by one playing General Zaragoza, with a tradition of cutting the hair of a new member of the troops for “lice.” The last battle occurs in the evening with the French troops climbing on airport side and the Mexican troops on the Río Consulado side. It is at this time that cannons with blanks are fired. When the French are defeated, they run down the mountain and through the Barrio del Carmen where they are chased and then “executed” at the area cemetery.[16] After the day’s events, there is a festival, dance and carnival.[15]

History

Pre Hispanic era

The emblem of the borough is the former Aztec glyph used to mark a village name Xochicán as it appears in the Mendocino Codex. The flower image means “place of fragrant flowers.”[4]

Except for the far west which was part of the island of Tenochtitlan, the Peñón de los Baños and a couple of very small islands in-between, the territory of the borough was covered by Lake Texcoco from the pre Hispanic period into the colonial period.[2][4] The oldest human settlements in the area were located in the Mixuhca and Peñón de los Baños, which were both originally islands in Lake Texcoco.[3] The eastern end of Tenochtitlan was associated with docks and markets that handled the produce and other items that came over the Lake’s waters into the city from other parts of the Valley of Mexico such as Texcoco, Chalco and Xochimilco. The lake in this area also contained part of the Nezahualcoyotl Dike, built to separate the shallow waters.[4]

The small islands on the lake were also inhabited. One of these was Mexicaltzingo, where the leader of Culhuacán allowed the Mexica to live for a while in exchange for military service. Today this area is at the intersection of Calzada de la Viga and Ermita Iztapalapa. Another area, Mixuhca, was a very small island in the lake and where it is said that one of the sons of Moctezuma II was born. The name is derived from Mixiuhtlán, which means “place of birth” for this reason. The Cerro el Peñón de los Baños was a recreational area for Aztec emperors. It contained a number of hot springs with high mineral content believed to be curative.[4]

Colonial era

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish laid out their own capital over the ruins of Tenochtitlán. The eastern end of this city corresponds to the La Merced, San Lázaro and Candelario de los Patos neighborhoods. However, these areas were overpopulated and un-hygienic because of the low, muddy condition of the lands here next to the lake, constantly subject to flooding.[3]

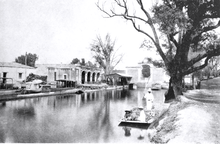

In the 17th century, the San Lazaro dike continued to define the border of Lake Texcoco with firm land. However, the process of the lake’s desiccation was already evident, expanding the island to allow Mexico City to grow eastward. The drying of the lake lead to the creation of a network of canals, of which the Jamaica and La Viga Canals were most important from the colonial period to the early 20th century. The La Viga Canal linked the La Merced market area to agricultural area southeast of the city, with docks for the canoes called “trajineras” right next to the market.[4]

In the 18th century, the San Antonio Tomatlán and La Candelaria churches were built in the neighborhoods of San Lázaro and Candelaria de los Patos.[4]

Independence to the present

During the 19th century, the lake continued to dry up, expanding Mexico City east. One of the roads built on this “new” land was Calzada Ignacio Zaragoza, which today leads to the highway to Puebla and Veracruz. Whether covered in lake or not, the territory of the borough became part of the Federal District of Mexico City when it was created in 1824 and has remained since. In the latter part of the century, a number of Mexico’s new rail lines terminated at the San Lázaro station, connecting Mexico City with Cuautla and Cuernavaca .[3][4] The urbanized area extended to what is now the Avenida Congreso de la Unión, with the formation of neighborhoods such as San Lázaro, Santo Tómas, Manzanares, La Soledad, Morelos and Moctezuma.[4] However, much of the land in the 19th century was still swampy with the exception of the far west and the Peñón de los Baños. By 1885, the area was drier but was sparsely populated.[3] A prison was also built in a neighborhood called Lecumberri between 1885 and 1900.[4]

At the end of the 19th century, Mexico City grew east with the establishment of Colonia Morelos, Colonia Penitenciaría and Romero Rubio. Most of the development was working class housing and industrial facilities. Most of the industries were initially connected with food processing and other activities related to the La Merced and Jamaica markets.[3] This would bring the city’s limits to Eduardo Molina and Avenida Congreso de la Unión by the beginning of the 20th century. Avenida Circunvalación, next to the La Merced Market, still connected to the La Viga Canal. What is now the borough then belonged to two districts: Mexico City proper and the municipality of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[4]

Francisco I. Madero and Pino Suárez were executed next to Lecumberri prison in 1913.[3]

In the 1920s, Calzada Ignacio Zarragoza was built to connect to the city center to the Puebla highway. This main road spurred the development of more subdivisions expanding the urban sprawl east. A large amount of land in this area belonged to a man named Alberto Braniff, who provided it to establish Mexico City’s first private airstrip in 1909, which became the Aeropuerto Central de la Ciudad de México in 1943. In 1954, the airport relocated, expanded and was reconditioned for international flights to become the Mexico City International Airport. This airport prompted the development of warehouses, hotels, and offices in the area.[3]

In the 1950s Viaducto Miguel Aleman was constructed after encasing the Tacubaya, Piedadad and Becerra rivers in concrete. The La Merced market was expanded and the Mercado Sonora was built.[4] In the mid 20th century, the process of lake drying and new subdivisions was still ongoing, with Colonia Cuatro Arboles begun in 1945, only five years after the lake in this area disappeared.[3]

The modern borough was created in 1970, when the center of Mexico City was split into a four boroughs with the other three being Benito Juárez, Cuauhtémoc and Miguel Hidalgo .[2][4] The borough was named to honor Mexican Revolution General Venustiano Carranza . By the end of the decade, the entire territory of the borough was urbanized with the exception of the Peñón de los Baños and a reservoir area called the Bordo de Xochiaca, which is now mostly green space.[3]

By 1982, informal stalls around the La Merced Market had invaded over 530,000 m2 (5,704,873 sq ft) and was threatening to increase indefinitely. This prompted the end of the market as the city’s main retail center in favor of a new market, Central de Abastos in Iztapalapa. La Merced remains the largest retail market for foodstuffs in Mexico City.[3]

In 2011, the borough broke the record for the world's largest torta sandwich, which measured fifty meters long, weighed 650 kg (1,433 lb) and was put together in three minutes 57 seconds with seventy different ingredients. The sandwich was created as part of the annual Feria de la Torta.[17]

Demographics

Since the 1990s, the borough has had a decrease in population, down from 462,806 from 2000. The borough’s population accounted for 10.4% of the District’s total in 1970. It accounted for 5.4% in 2000. One main reason for the decrease is the conversion of land from residential to commercial use.[3]

The dominant religion is Roman Catholicism with over 90% of the population professing this faith. As of 2005, 4,489 people spoke an indigenous language, 1.1% of the total.[3]

Education

There are 456 schools in the borough: 156 preschools, 200 primary schools, 73 secondary schools, 8 vocational high schools and 19 high schools. However, About eighty percent of the population has an education of less than high school level.[3]

Public high schools of the Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS) include:[18]

- Escuela Preparatoria Venustiano Carranza "José Revueltas Sánchez"

Socioeconomics

About 54% of the total population twelve or over is economically active. Most workers are between 35 and 39 years of age. As of 2000, over 98% of the working population was employed in either the formal or informal economies. Just under 80% are employed in commerce, 17.5% are employed in manufacturing and construction and .1% in agriculture.[3]

The number of housing units in the borough has risen from 112200 units with an average occupancy of 3.3 in 1950 to 117800 units with 4.4 occupants in 1990. As of 1995, the average residential building was fifty years old. From 1990 to 2005, the numbers changed only slightly with 118400 units and 3.9 people per household. The improvement has much to with the decreasing population. Sewerage and electricity is available in over 97% of residential units but running water exists in just under 87%. Those without running water in the apartment have shared source of supply.[3]

Transportation

TAPO

The Terminal de Autobuses de Pasajeros de Oriente, better known as TAPO is the main bus terminal for interstate travel to the east and southeast.[4] It is located next to Metro San Lázaro and marked by its very large dome covering the structure. It was constructed by architect Juan José Díaz Infance and inaugurated in 1978. The outer rim of the circular interior contains ticket counters and boarding areas for bus lines such as Autobuses Unidos. The center contains a food court and other businesses.[19]

Mexico City airport

Mexico City International Airport, known officially as Aeropuerto Internacional de Benito Juárez, is the main airport for Mexico City. It was formally named after the 19th century president Benito Juárez in 2006. The airport is owned by Grupo Aeroportuario de la Ciudad de México and operated by Aeropuertos y Servicios Auxiliares, the government-owned corporation, who also operates 21 others airports through Mexico. It is the country’s busiest airport with 32 domestic and international airlines and offers direct flights to more than 100 destinations worldwide. In 2010, the airport served 24,130,535 passengers.

Other transportation

In total, the borough has 4,958 roads, 5.1% of the total of the Federal District. The most important roads include Anillo Periférico, Circuito Interior, Calzada Ignacio Zaragoza and Viaducto Miguel Aleman. Next in importance are Fray Servando Teresa de Mier, Eje 1 Oriente, Eje 2 Oriente (Avenida Congreso de la Unión ), Eje 3 Oriente, Eje 3 Sur, Eje 2 Sur, Eje 1 Norte, and Eje 2 Norte.[3][7]

The high concentration of people and businesses has resulted in an extensive public transportation network which includes the Mexico City Metro, trolleybuses and various bus lines. The Metro lines that cross the borough are Line 1, Line 4, Line 5, Line 9, and Line B, with thirty six stations within borough limits.[3]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Venustiano Carranza (Federal District). |

References

- 1 2 3 "Geografía" [Geography] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Venustiano Carranza. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Demarcación Territorial Venustiano Carranza (delegación)" [Territorial subdivision of Venustiano Carranza (borough)] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaria de Turismo Distrito Federal. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 "Venustiano Carranza". Enciclopedia de Los Municipios y Delegaciones de México - Distrito Federal (in Spanish). Mexico: INAFED. 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "La Delegación a Través de la Historia" [The Borough Over Time] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Venustiano Carranza. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Reforestan con 15 mil árboles la delegación Venustiano Carranza" [Reforesting Venustiano Carranza borough with 15,000 trees]. Excelsior (in Spanish). Mexico City. July 4, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Magdalena Mixhuca" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaria de Turismo Distrito Federal. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Venustiano Carranza" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaria de Turismo Distrito Federal. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Turismo" [Tourism] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Venustiano Carranza. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 "Mercados Populares" [Popular Markets] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Venustiano Carranza. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Lecumberri, el palacio negro" [Lecumberri, the black palace]. El Sol de Zacatecas (in Spanish). Zacatecas. January 25, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Palacio Legislativo San Lázaro – México" [Legislative Palace San Lázaro] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Grupo ArqHys. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Museo Legislativo" [Legislative Museum] (in Spanish). Mexico: Cámara de Diputados. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Santuarios Religiosos" [Religious Sanctuaries] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Venustiano Carranza. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Inaugura Venustiano Carranza nuevo centro cultural" [Venustiano Carranza inaugurates new cultural center]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. February 4, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- 1 2 "Tradiciones" [Traditions] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Venustiano Carranza. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ José Carlos Aviña (May 5, 2008). "Rememoran Batalla de Puebla en Peñón de los Baños" [Remembering the Battle of Puebla at Peñón de los Baños]. El Sol de México (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Rompen récord mundial con la torta más grande" [Break record the largest torta sandwich]. El Economista (in Spanish). Mexico City. July 27, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Planteles Venustanio Carranza." Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal. Retrieved on May 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Terminal de Autobuses de Pasajeros de Oriente" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaria de Turismo Distrito Federal. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

External links

- (Spanish) Delegación Venustiano Carranza official site

Coordinates: 19°25′00″N 99°06′50″W / 19.41667°N 99.11389°W