Jean-Max Albert

| Jean-Max Albert | |

|---|---|

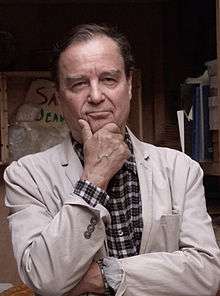

Jean-Max Albert, Paris, September 2014 | |

| Born |

Jean-Max Louis Albert 25 July 1942 Loches, France |

| Nationality |

|

| Known for | Painting, Sculpture, Literature, |

Jean-Max Albert is a painter, sculptor, writer, and musician. He has published theory, artist's books, a collection of poems, plays and novels inspired by quantic physics. He perpetuated a reflexion initiated by Paul Klee and Edgar Varèse on the transposition of musical structures into formal constructions. He created plant architectures which come close to Site-specific art, Environmental sculpture and Generative art.

Biography

Jean-Max Albert French: [ʒɑ̃maks albɛʁ] was born in 1942, in Loches, France. He studied at the Ecole Régionale des Beaux-Arts d'Angers then at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts de Paris, with frequent visits to the Louvre, across the river (cf An Afternoon in the Louvre). His student friends introduced him to the works of Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, Louis Kahn, Carlo Scarpa… Albert was also a trumpet player (1962–64),[1] joining Henri Texier’s quintet with Alain Tabarnouval in the beginnings of Free Jazz.[2] The group performed in clubs, festivals and concerts.[3]

In 1975 he initiated the group show Serres in François Horticultural Greenhouses, Magny-in-Vexin.[4] Sculptor Mark di Suvero invited him to New York City, the first of many visits to United States. In 1981 he met Sara Holt, whose sculpture and photographs were inspired by astronomy. They collaborated and carried out various public art projects.[5] Travels in Europe, North Africa, Middle East.[6]

In 1985 he took part to Ars Technica Association connected to the Cité des Sciences et de l'Industrie uniting philosophers, artists, scientists such as Jean-Marc Levy-Leblond, Claude Faure, Sara Holt, Piero Gilardi, Jean-Claude Mocik, reflecting on the relationship between art and new technologies.[7] In 1990, he was commissioned by the architects Wylde-Oubrerie as collaborating artist for the realisation of Miller House[8] in Lexington. Then invited to give lectures and workshops for the University of Architecture of Kentucky and then for the Art Center of Design in Pasadena.

Edgar Varese, in his comments, often refers to solid geometry[9] and György Ligeti to static music.[10] His experience in the musical field enabled Jean-Max Albert to exchange on these subjects with musicians such as : György Ligeti, Steve Lacy, Barney Wilen, François Tusques.[11] He creates monumental trellis-works : Iapetus (1985) which refers to the structure of Thelonious Monk's ‘’Misterioso’’ »,[12] Ligeti (1994), which refers to Ligeti’s «static sonorous surfaces». A book and exhibition followed : Thelonious Monk Architecte (2001). A collaboration with pianist and composer François Tusques results in 80 short films: Around the Blues in 80 Worlds (2008).[13][14] With Jean-Claude Mocik, he is coauthor of the project Midi-Pile started in 1994.[15]

Beside sculptures related to music, he conceived a project dedicated to the vegetation itself, in terms of biological activity. The utopian Calmoduline Monument is based on the property of a protein, calmodulin, to bond selectively to calcium. Exterior physical constraints (wind,rain, etc.) modify the electric potential of the cellular membranes of a plant and consequently the flux of calcium. However, the calcium controls the expression of the calmoduline gene. The plant can thus, when there is a stimulus, modify its « typical » growth pattern. So the basic principle of this monumental sculpture is that to the extent that they could be picked up and transported, these signals could be enlarged, translated into colors and shapes, and show the plant’s « decisions ». This permanent show, installed in a public place, would suggest a level of fundamental biological activity.[16][17]

Painting

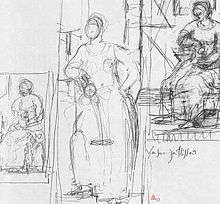

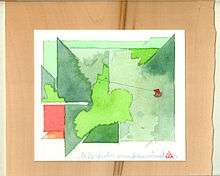

Portraits of the Loire ; Framing Sculptures ; Que voit-on quand on ne regarde pas ? (What do you see when you are not looking ?)[18] or subjects more episodical : Memories of a Train Journey ; Thelonious Monk Architect ; Afternoon in the Louvre or The Carpenters’ Design, Albert’s painting are not limited to a particular style. He likes to cite Chinese masters of the classical period, mentioned by Matisse [19] who taught the student to identify with his subject: to paint the tree in its expansion, the rock in its rugged massiveness… and mentions that the precept can be also found in General semantics by Alfred Korzybski : «To be efficient, a language should be similar in its structure to the structure of the event it is supposed to represent». This idea that an artwork should be autonomous — epoch and even author's identity, taking second place — has provoked vigorous discussions with artists friends, notably with painter Joan Mitchell.[20]

Sculpture

Monumental sculpture

Around 1973, a meeting with the architect Louis Kahn, led him to compare the relationship between paint and canvas with that of vegetation on trellis.[21] Jean-Max Albert then revisited the tradition of trellis-work,[22][23] 18th-century utopic architecture and, finally, created vegetal architecture which came close to Land art and Environmental Sculpture.[24][25] It was comparable to the work of Gordon Matta-Clark, or Nils Udo, his neighbour in the Wissenschaftszentrum exhibition in Bonn in 1979.[26] From Vicenza[27] at the Hôtel de Sully, Paris, 1975 (in collaboration with Fougeras Lavergnolle) until the project O=C=O for the "Parco d' Arte Vivente" in Torino, 2007 (by way of the Festival of the Gardens of Chaumont, 1996), Albert created many architectural and vegetal sculptures on trellis-work in the field of Site-specific art, Environmental sculpture and Generative art.[28]

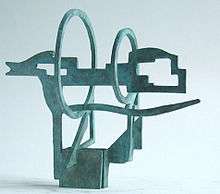

Observation sculptures (= Sculptures de visées)

Parc de La Villette, Paris 1986

Observation Sculpture, 2002

While monumental sculpture is meant to be installed within an urban or rustic space, Albert’s Observation Sculpture aims to concentrate the surrounding environment in the sculpture. When looking in the Observation Sculpture through its sights (an aperture or circles), the space beyond is (roughly) framed. Combining the different perspectives framed, the little sculpture, usually in bronze, takes shape after the space it is aiming at. An Observation Sculpture proposes a summary of this space concentrated, agglomerated and stuck together in a kind of core, like a geometric model of the site’s character.[29][30]

Anamorphosis

Albert realized Un carré pour un square, Cube fantôme and Reflet anamorphose,[31] three pieces according to anamorphosis principle as described by Matilde Marcolli : « If the vector space one starts with is the 3-dimensional space, whose vectors have 3-coordinates v = (x1, x2, x3), then, as long as v is nonzero and a real number λ is also nonzero, the vector v = (x1, x2, x3) and the vector λv = (λx1, λx2, λx3) point along the same straight line and we consider them as being the same point of our projective space. » [32]

Public works

- Vicenza, Hotel de Sully, Paris 1977

- Attique, Künstler-Garten, Wissenschaftszentrum, Bonn, Germany, 1979

- Iapetus,[33] Parc de l'école des beaux-arts, Angoulême, 1985, 45°39’15.246’’N0°8’54.834’’E

- Rayon, Centre Culturel Français, Damascus, Syria, 1986

- Sculptures de visées,[34][35] and Reflet anamorphose Parc de la Villette, Paris, 1986, 48°53’33.8’’N2°23’26’’E

- Cube fantôme, ZI de Goussainville, 1986

- Autumn in Peking, South Pasadena, USA, 1987, 34°6’40’435’’N118°8’33.619’’W

- Vers l'étoile polaire, Parc des Maillettes, Melun Sénart, 1987

- Un carré pour un square,[36][37] Place Frehel, Paris, 1988

- Une horloge végétale, Square Héloïse et Abelard, 24 rue Dunois, Paris, 1988, 48°49’52.745N2°22’13.12’’E

- Planches,[38] Terrasse du Musée de la Toile de Jouy, à Jouy-en-Josas, 1990, 48°46’8.591’’N2°9’5.868’’E

- Ligeti, Rectorat de Rouen, Rouen, 1994, 49°26’35’’N1°5’4.6’’E

- Auriga, Rond-point Montaigne, Angers, 1995, 47°27’59’’N 0°31’30’’W

- Tombeau de Bartillat, Etrépilly, 1997, 49°2’18’’N 2°55’53.2’’E

Writing

Books

- Tuteurs Fabuleux, Éditions Speed, Paris, 1978. FRBNF34609833

- Lithium Migrants, Éditions Cheval d’Attaque, Paris, 1981. ISBN 2-86200-017-5

- Les nouveaux voyages du capitaine Cook, Éditions ACAPA, Angoulême, 1984. ISBN 2-904353-00-3

- Thelonious Monk Architect, Fleeting white Space, New York, 2001.

- Space in Profile,[39][40] (French and English), Les Éditions de La Villette, Paris, 1993. ISBN 2-903539-21-9

- Le tour du blues en 80 mondes, Sens & Tonka Editeurs, Paris, 2005. ISBN 2-84534-118-0

- Les Querpéens I, Emma Qun'q,[41] Les Éditions du Quintelaud, Paris 2009. ISBN 978-2-9533484-0-8

- Les Querpéens II, Ray Quernöck,[42] Les Éditions du Quintelaud, Paris 2012. ISBN 978-2-9533484-5-3

Poetry

Theatre

- La machine à laver le temps, Mise en scène de Miguel Borras, Théâtre des Cinquantes, juin 1998

- Nos mains sous la neige, La comète. Mise en scène de Fabrice Scott donnée au Théâtre du Trianon, Paris novembre 1998 ; Théâtre Adyar Paris, juin 1999

Articles

- Soulages, Opus n°57, 1975

- De l'architecture transparente, Opus n°65, 1978

- De l'architecture transparente,[45] Lotus international n°31, 1982

- Vuthemas, Ars technica n°4, 1991

- Mathesis singularis, Ars technica n°7, 1992

- Une obscurité infiniment lumineuse, Alliages n°19, 1994

- Jean-Bernard Métais et Sir George H. Darwin, Temps imparti, Éditions Beaudoin Lebon, Paris, 2002

- Thelonious Monk Architecte, L'art du jazz, Éditions Le Félin, Paris, 2009 [46]

Videos

- Le tour du Blues en 80 mondes.[47] 80 short films with pianist and composer François Tusques.[48][49][50]

Music

Choreographies and compositions

- A treat “Espaces structurés” Videos by Hervé Nisic, choreography by Michala Marcus and Jean-Max Albert, music by Kent Carter.[51]

- Carlotta's Smile, Environment and Choreography with Michala Marcus, Music Carlos Zingaro, AR CO, Lisbonne, Portugal, 1979

- Morgane Amalia, Choreography with Michala Marcus, 2nd Symposium d'art contemporain d'Angoulême, 1980[52]

- Kaluza, 21 pièces pour piano et chorégraphie with Sarah Berges. Dance Mission Theatre, San Francisco, 2013 [53]

Exhibitions

Exhibition Hôtel de Sully, Paris, 1977

Individual

- Carlotta's Smile, AR CO, Lisbonne, Portugal, 1979

- Lithium Migrants, Galerie Françoise Palluel, Paris, 1981

- Lithium Migrants, Galerie Richard Foncke, Gand, Belgium, 1981

- Jean-Max Albert Peintre, ACAPA, Hôtel Saint-Simon, Angoulême, France 1982

- Lumen poème,[54][55] CRDC, Rosny-sur-Seine, 1984

- De la roue de sel à la queue du champ,[56][57][58] Galerie Charles Sablon, Paris, 1987

- Il fait encore assez clair pour voir qu'il commence à faire sombre, Galerie Intersection 11/20, Paris, 1991

- Framing and Observation Sculptures,[59] Fleeting White Space, Antwerpen, Belgium, 1994

- Thelonious Monk architecte, Aïda Kebadian, Paris, 2001

- La collection Trousseau, Aïda Kebadian, Paris, 2002

- Portraits de la Loire, Abbaye de Bouchemaine, Maine & Loire, France, 2002

- Souvenir du voyage en train, Aïda Kebadian, Paris, 2010

Participations

- Vers une nouvelle architecture, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1978

- Sculpture Nature, Centre d'Arts Plastiques Contemporain, Bordeaux, France,1978

- Künstler-Garten, Wissenschaftszentrum, Bonn, Germany, 1979

- A la recherche de l'urbanité,[60] Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1980

- Actuele Franse Kunst,[61] International Cultureel Centrum, Antwerpen, Belgium, 1982

- Pavillon d'Europe, Galerie de Séoul, Seoul, Korea, 1982

- Hommage à Joseph Albers, Musée d'Angoulême, France, 1982

- Images et imaginaires d'architecture, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1984

- Inventer 89,[62] Grande halle du Parc de la Villette, Paris, 1987

- L'art au défi des technosciences? Pavillon Tusquet, Parc de la Villette, Paris, 1992

- L'art renouvelle la ville, Musée National des Monuments Français, Paris, 1992

- Ars Technica, ExtraMuseum, Turin, Italy, 1992

- Useless Science, MoMa, New York, USA, 2000

- Fragmentations a constructed world, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de Saint-Brieux,[63] 2007

- Le musée côté jardin,[64] Fond Régional d'Art Contemporain de Bretagne, 2007

- Dalla Land arte alla bioarte,[65] Parco d'Arte Vivante, Turin, Italy, 2007

- Tables à Desseins,[66] La tannerie, Bégard France 2013

- Du dessin à la sculpture,[67] Musée Manoli, La Richardais, France, 2014

Public Collections

- Centre Pompidou CCI, Éléments pour Brancusi,[68] 1980

- Fond Régional d'Art Contemporain de Bretagne, Blue Monk, Vicenza, 1982

- Fond National d’Art Contemporain, Acronesia Mutikos, 1982

- Artothèque, Angers, Passé composé, 1984

- Fond Régional d'Art Contemporain Poitou-Charente, Iapetus, 1984

- Fond National d’Art Contemporain, 2 Sculptures de visées,[69] 1989

- Musée Paul Delouvrier, Que voit-on quand on ne regarde pas ?[70] 1989

Notes and references

- ↑ Dictionnaire du jazz, Sous la direction de Philippe Carles, Jean-Louis Comolli et André Clergeat. Éditions Robert Laffont, coll. "Bouquins", 1994

- ↑ Cité de la Musique

- ↑ Musique Française

- ↑ Michel Cosnil-Lacoste, Cimaises en rase campagne, Le Monde, 7 July 1975

- ↑ Bruno Suner, Relier ciel et ville, Urbanisme n°219, 1987

- ↑ Realization for the French Cultural Center in Damascus, Syria, 1986

- ↑ http://www.arsmeteo.org/arsmeteo/main.php?page=evento&id=107&height=640&width=800

- ↑ Miller House Miller House, GA n°35, July 1992. (in English)

- ↑ Philippe Lalitte, « Rythme et espace chez Varèse », Filigrane ,

- ↑ Un entretien entre György Ligeti et Josef Häusler « d’Atmosphères à Lontano», La musique en jeu, Editions du Seuil, 1974

- ↑ Jedediah Sklower, Free Jazz, la catastrophe féconde, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2006

- ↑ Michel Ragon, Jean-Max Albert «Iapetus», L’art abstrait vol.5, Éditions Maeght, Paris, 1989

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDO-l2wLNS9uiVOueyhp_mQ

- ↑ http://issuu.com/pauldavidkahn/docs/new_2005_2

- ↑ http://www.artshebdomedias.com/article/291210-jean-claude-mocik-artiste-est-mort-vive-artiste?page=0

- ↑ Space in profile/ L'espace de profil,

- ↑ Intra-and Intercellular Communications in Plants, Millet & Greppin Editors, INRA, Paris, 1980, p.117 (in English)

- ↑ Musée Paul Delouvrier, Que voit-on quand on ne regarde pas ? 1989

- ↑ Henri Matisse, ‘’Ecrits et propos sur l’art‘’, Herman, Paris, 1972, p.167

- ↑ Patricia Albers, Joan Mitchell : Lady Painter, A life, Knof, 2011

- ↑ Jean-Louis Pradel, Les monuments de treillage de Jean-Max Albert, Opus n°65, 1978

- ↑ L'ivre de pierre

- ↑ Hubert Beylier, Bénédicte Leclerc, Treillage de jardin du XIV au XX siècle, Éditions du patrimoine, Paris, 2000, p. 172-173

- ↑ Jean-Max Albert O=C=O, Franco Torriani, Dalla Land arte alla bioarte, Hopefulmonster editore Torino, 2007, p. 64-70

- ↑ Jean-Paul Pigeat, Jean-Max Albert et Emilio Ambasz, «Le nymphée et la profondeur», Manuel des jardins de Chaumont, 1996

- ↑ Wolfgang Becker, Sculpture Nature, Centre d'Arts Plastiques Contemporain, Bordeaux, 1980

- ↑ Dominique Richir, Tuteurs Fabuleux, Opus n°64, octobre 1976

- ↑ Bruno Suner, L'art du passage à Saint Nazaire, Urbanisme n°214, 1986

- ↑ Jardin-de-la-Treille, wikimapia

- ↑ Bruno Suner, Les sculptures de visées du Parc de La Villette, Urbanisme n°215, 1986

- ↑ http://www.its.caltech.edu/~matilde/SpaceMathArticle.pdf

- ↑ Matilde Marcolli, The notion of Space in Mathematics through the lens of Modern Art, Century Books, Pasadena, July 2016

- ↑ FRAC Poitou-Charente

- ↑ Les jardins du parc de la Villette

- ↑ Parc de La Villette (in English)

- ↑ Fresques et murs-peint parisiens

- ↑ Monique Faux, L'art renouvelle la ville, Editions Skira, Paris 1992

- ↑ Musée de la toile de Jouy

- ↑ Musée d’Art Contemporain, Marseille, L'Espace de profil/ Space in Profile

- ↑ Frédéric Mialet, Exercice sur le vide, D'A n°45, mai 1994

- ↑ Le nouvel Attila

- ↑ La lucarne des écrivains

- ↑ Derry O'Sullivan, Ceamara Jean-Max Albert, An Guth, Dublin, 2008, (in Gaelic)

- ↑ Derry O'Sullivan, Caemara/Ceamara, Estepa Editions, Paris 2010

- ↑ "Lotus international"

- ↑ L'art du jazz

- ↑ http://issuu.com/pauldavidkahn/docs/new_2005_2

- ↑ Bay area reading, Berkeley University, USA, 2007

- ↑ Free Jazz Cinéma journées approxinématives, Théâtre de Montreuil, 2007

- ↑ Clifford Allen, ‘’François Tusques’’ The New York City Jazz Record p10, June 2011 (in English)

- ↑ Projections : La Vitrine, Paris; American Center, Paris ; Global Village, New York ; The Kitchen, New York, 1981. Julie Gustafson, Global Village Program 1981, New York

- ↑ Dominique Richir, Morgane Amalia, Opus n°77, 1980

- ↑ Sarah Berges Dance

- ↑ Carole Naggar, Lumen poème, Centre Régional d'Art Contemporain, Rosny-s-Seine, France, 1984

- ↑ Jean-Louis Pradel, Lumen de Sara Holt et Jean-Max Albert, L'événement du jeudi, 8 novembre 1989

- ↑ Jean-Louis Pradel, Jean-Max Albert, L’Evénement du jeudi, 17 septembre 1987

- ↑ France Huser, Jean-Max Albert, Galerie Charles Sablon, Le nouvel observateur, 25 septembre 1987

- ↑ Anne Dagbert, Jean-Max Albert, Galerie Charles Sablon, Art Press n°119, 1987

- ↑ Sarah Mc Fadden ‘’Jean-Max Albert «Sculptures»’’, The Bulletin n°24, Bruxelles, June 16th 1994

- ↑ Un pavillon de treillage à Pau, Biennale de Paris, CCI Centre Georges Pompidou, Éditions Academy, Paris, 1980

- ↑ Jean-Louis Pradel, Actuele Franse Kunst, International Cultureel Centrum-Antwerpen, 1982

- ↑ F Reynaert, Inventer 89, Libération, 13 octobre 1987

- ↑ Fragmentations a constructed world

- ↑ Le musée côté jardin

- ↑ Dalla Land arte alla bioarte

- ↑ Tables à Desseins

- ↑ [Du dessin à la sculpture

- ↑ Centre Pompidou

- ↑ Fond National d'Art Contemporain

- ↑ Musée Paul Delouvrier