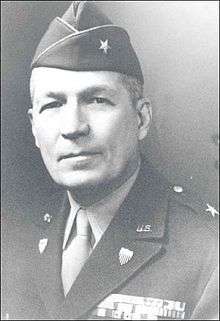

James C. Dozier

| James C. Dozier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "Mr. National Guard" |

| Born |

February 17, 1885 Galivants Ferry, South Carolina |

| Died |

October 24, 1974 (aged 89) Columbia, South Carolina |

| Buried at | Elmwood Cemetery |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1904 - 1959 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | 118th Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars |

Pancho Villa Expedition World War I World War II |

| Awards |

Medal of Honor Purple Heart |

James Cordie Dozier (February 17, 1885–October 24, 1974) a native of South Carolina was a United States Army officer who received the Medal of Honor for heroism on October 8, 1918 during World War I.

Early life

Dozier was born on February 17, 1885, at Galivants Ferry in Horry County. The descendant of a long line of Palmetto State Citizen-Soldiers who had served from the American Revolution, through the Spanish–American War, Dozier began his military career with Company H, 118th Infantry Regiment on September 3, 1904.

In August 1916, Dozier was sent with the 118th Infantry Regiment to El Paso, TX. There, they joined Brig. Gen. John J. “Blackjack” Pershing’s Punitive Expedition to protect U.S. border towns from Mexican General Pancho Villa’s forces. Company H returned home to S.C. in December. Four months later on April 16, 1917 Dozier’s unit was activated for World War I. While training at Camp Sevier (near Greenville), over the next several months, Dozier was commissioned a 2nd Lt. in July and 1st Lt. in November. His unit boarded a ship bound for France on May 11, 1918. Provided by: Maj. Scott Bell, S.C. National Guard Historian

Military service

World War I

Between May and September 1918, the 118th Infantry Regiment trained and moved through the allied lines to become the first American force to face Germany’s “impregnable” Hindenburg Line on September 27. Over the next month, the regiment advanced through 18,000 yards of enemy territory, 15,000 yards of which was made while the regiment was in the front line spearheading numerous attacks. However, it was at Montbrehain on October 8, Dozier became one of six S.C. National Guardsmen to receive the Medal of Honor.

On October 8, at five in the morning, G Company was ordered “Over the Top.” The unit advanced approximately one mile before its commander was wounded and Dozier, who had already been shot in the shoulder by a sniper, assumed command. Soon after, the Germans sent out half a dozen machine gun crews in advance of their line. According to Dozier one was particularly well advanced. “We could see men from my company and men of the other companies on our right and left falling from machine gun fire.” Locating the source of trouble, Dozier signaled his company to lie down and seek as much concealment as possible. He then ordered a machine gun crew to fire just over the heads of the German gunners so they couldn’t look over the top of the pit in which they were concealed. He and Private Callie Smith advanced on the left flank of the machine gunners until they were within 20 yards of the enemy.

Around 8:30 a.m. he signaled his machine gun crew to quit firing and dashed upon the Germans in the hole. “One of the machine gunners was about to get me with his revolver when Callie Smith downed him,” said Dozier. The two knocked out the entire squad of seven machine gunners in this advanced position. Dozier continued leading his men for the next two and a half hours until all the machine gun nests had been silenced and G Company’s objective had been taken. He and the unit also captured approximately 470 prisoners. At this point, the “Great War” was over for Dozier. He spent the next three months in hospitals recuperating from his wound. On January 21, 1919, General Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force pinned the Medal of Honor to Dozier’s chest.[1]

Citizen-Soldier Returns Home

When the 118th returned to Camp Jackson (now Ft. Jackson) from overseas, the U.S. government was gearing up for a “Victory Liberty Loan Campaign” to raise $4.5 billion in war bonds to pay off the nation’s debt from World War I. Dozier’s achievement on October 8, was selected by the government as one of the 12 most remarkable exploits during the war. He and 11 other Medal of Honor recipients spent three weeks (April 21 – May 10) touring the country helping to raise $5.2 billion (approx. $63 billion today) in bond subscriptions.

After completing this mission, Dozier returned to civilian life. He also continued his courtship with Winthrop College student Tallulah Little, whom he had corresponded with throughout the war. In a scrapbook she kept of Dozier during and after the war are endearing telegrams he sent her while separated. One of them relates to an upcoming banquet the students of Winthrop hosted in honor of the homecoming of our Soldiers. In the telegram Dozier wrote “Miss Lula Little, I’m coming Tuesday. My place at the banquet is with you. It is fine to be back home. Love, Jim.” The two were married the following June in Laurens.[2]

Dozier Honors a Friend

Dozier rejoined the S.C National Guard on December 1, 1920, to organize the “Frank Roach Guards,” of Rock Hill in honor of Roach, a fellow Rock Hill Soldier from Company H who lost his life in Flanders Field. On September 1, 1921, Dozier was promoted to Major and assigned to command 3rd Battalion of the 118th Infantry Regiment. On January 1, 1923, he was appointed secretary of the State Board of Welfare which he held until the unexpected death of Adjutant General Robert E. Craig. A week later on January 22, 1926, Maj. Dozier was appointed The Adjutant General (TAG) by Governor Thomas C. McLeod to fill the unexpired term of Craig. At the time, Guard strength consisted of 2,104 officers and men. The Guard had two armories, one in Columbia, the other in Beaufort. The annual budget was $118,812.00.[3]

Adjutant General of South Carolina

Shortly after becoming TAG, Dozier was asked by the War Department to take over custody of Camp Jackson (Ft. Jackson) which had been abandoned by the Army on April 25, 1922. He is credited for helping to preserve the Camp and growing it between the World Wars and during the Great Depression (1929–1939). In fact, Dozier Hall at Ft. Jackson was dedicated in his honor on May 15, 1998, by Maj. Gen. Stanhope S. Spears, S.C. TAG and Maj. Gen. John A. Fan Alstynein, a past commander of Ft. Jackson.

In 1928, Camp Jackson was chosen as a training center for the 30th “Old Hickory” Division. Following the stock market crash the next year, non-farming jobs became scarce across the state. Dozier determined to help the unemployed by seeking Works Progress Administration (WPA) funding for Camp Jackson and construction of armories and other Guard facilities throughout S.C. Although it would take another four years to receive WPA funds for new armories, $86,656.00 was allocated for Dozier’s new construction and maintenance projects at Camp Jackson and repairs at Ft. Moultrie’s Guard facilities.

In 1936, the Guard dedicated 23 new armories and received funding for seven more at a cost of $494,759.00. “These new buildings constructed around the state is indicative, not only of civic pride, but of an increased interest in our National Guard,” wrote Dozier.

Dozier’s efforts to help S.C. communities were so successful, the WPA awarded money in 1938, to construct five additional armories and another $154,980 to make general improvements and repairs at Camp Jackson. This put the camp in what Dozier called “first-class condition” for the more than 8,000 Guard Soldiers from the 30th Division who used the camp each year. These improvements proved tremendously beneficial when the Army’s 6th Division reactivated Camp Jackson following Hitler’s successful Blitzkrieg into Poland in November 1939.

In September 1940, the winds of war were again blowing across the nation and the 118th Infantry Regiment was activated. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, all 3,671 Guardsmen were activated for World War II. In order to ensure key logistical installations throughout the state continued to be protected, the S.C. Legislature adopted Act No. 54, on March 21, 1941, establishing the S.C. Defense Force to serve in the absence of the Guard. Dozier immediately organized State Guard units in 80 towns, with a strength of 6,000 men.

After World War II, the National Guard had to be completely reorganized and rebuilt. In December 1946, the process began and Dozier became an advocate for General George C. Marshall’s plan for the post-war National Guard. Marshall believed a bigger, more powerful, well funded National Guard would help deter future aggression by America’s enemies. “I sincerely believe that if we had given our security its proper attention, the Axis nations would not have started the war,” said Dozier.

A good portion of the reorganization and rebuilding Dozier undertook in 1946, included the development of the S.C. Air National Guard. The Guard received 25 P-51s, one C-47 and four AT-26s at Congaree Air Base (McEntire Joint National Guard Base). By the following July, 94 of the new 116 authorized Army Guard units were also organized. The number of personnel authorizations continued to increase and by 1950, there were 12,683 S.C. Soldiers and Airmen serving.

In 1951, Dozier’s 25-year effort to acquire appropriations from the S.C. Legislature for new armory construction came to fruition. The state provided $350,000 under an agreement with the federal government which provided 75 percent of the cost of building the armories. As a result, 14 new armories were built. In 1957, funding for 10 additional armories and the renovation of eight old ones was also approved by the Legislature.

By the time of Dozier’s retirement fifty years ago on January 19, 1959, he had received many awards and accolades from leaders across the nation. The S.C. National Guard’s budget had grown from $118,812.00 (1926), to $6,230,159.62 (1959). During a time when armory utilities, maintenance and operation were a much smaller portion of the Guard’s budget, “Mr. National Guard” had accomplished—what was considered at the time—the greatest and most permanent achievement ever accomplished during the term of office of any Adjutant General, the construction of permanent armories throughout the state. Appropriately, the name Dozier will forever be synonymous with the S.C. National Guard.[4]

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, U.S. Army, Company G, 118th Infantry, 30th Division. Place and date: Near Montbrehain, France, October 8, 1918. Entered service at: Rock Hill, S.C. Born: February 17, 1885, Galivants Ferry, S.C. G.O. No.: 16, W.D., 1919.

Citation:

In command of 2 platoons, 1st. Lt. Dozier was painfully wounded in the shoulder early in the attack, but he continued to lead his men displaying the highest bravery and skill. When his command was held up by heavy machinegun fire, he disposed his men in the best cover available and with a soldier continued forward to attack a machinegun nest. Creeping up to the position in the face of intense fire, he killed the entire crew with handgrenades and his pistol and a little later captured a number of Germans who had taken refuge in a dugout nearby.

Decorations

| Medal of Honor | |

| Purple Heart | |

| Mexican Service Medal | |

| World War I Victory Medal with three battle clasps | |

| American Campaign Medal | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| Military Cross (United Kingdom - World War I award) | |

| Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (France - World War I award) | |

| Croix de guerre 1914–1918 with Palm (France - World War I award) | |

See also

Notes

References

- "Congressional Medal of Honor Society". Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- "James C. Dozier". Claim to Fame: Medal of Honor recipients. Find a Grave. Retrieved 2007-12-23.