IsaMill

The IsaMillTM is an energy-efficient mineral industry grinding mill that was jointly developed in the 1990s by Mount Isa Mines Limited ("MIM", a subsidiary of MIM Holdings Limited and now part of the Glencore Xstrata group of companies) and Netzsch Feinmahltechnik ("Netzsch"), a German manufacturer of bead mills.[1] The IsaMill is primarily known for its ultrafine grinding applications in the mining industry, but is also being used as a more efficient means of coarse grinding.[2][3] By the end of 2008, over 70% of the IsaMill’s installed capacity was for conventional regrinding or mainstream grinding applications (as opposed to ultrafine grinding), with target product sizes ranging from 25 to 60 µm.[4]

Introduction

While most grinding in the mineral industry is achieved using devices containing a steel grinding medium, the IsaMill uses inert grinding media such as silica sand, waste smelter slag or ceramic balls.[2] The use of steel grinding media can cause problems in the subsequent flotation processes that are used to separate the various minerals in an ore, because the iron from the grinding medium can affect the surface properties of the minerals and reduce the effectiveness of the separation.[5] The IsaMill avoids these contamination-related performance issues through the use of an inert grinding medium.

First used in the Mount Isa lead–zinc concentrator in 1994, by May 2013 there were 121 IsaMill installations listed in 20 countries, where they were used by 40 different companies.[6]

IsaMill Operating Principles

The IsaMill is a stirred-medium grinding mill, in which the grinding medium and the ore being ground are stirred rather than being subjected to the tumbling action of older high-throughput mills (such as ball mills and rod mills). Stirred mills often consist of stirrers mounted on a rotating shaft located along the central axis of the mill.[7] The mixing chamber is filled with the grinding medium (normally sand,[2] smelter slag,[2] or ceramic[7] or steel beads[7]) and a suspension of water and ore particles,[7] referred to in the minerals industry as a slurry. In contrast, ball mills, rod mills and other tumbling mills are only partially filled by the grinding medium and the ore.

In stirred-medium mills, the stirrers set the contents of the mixing chamber in motion, causing intensive collisions between the grinding medium and the ore particles and between the ore particles themselves.[7] The grinding action is by attrition and abrasion, in which very fine particles are chipped from the surfaces of larger particles,[8] rather than impact breakage. This results in the generation of fine particles at greater energy efficiency than tumbling mills.[7] For example, grinding a pyrite concentrate so that 80% of the particles are less than 12 µm (0.012 mm) consumes over 120 kilowatt-hours per tonne (kWh/t) of ore in a ball mill using 9 mm balls, but only 40 kWh/t in an IsaMill using a 2 mm grinding medium.[9]

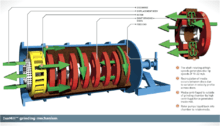

The IsaMill usually consists of a series of eight disks mounted on a rotating shaft inside a cylindrical shell (see Figure 2).[10] The mill is 70–80% filled with the grinding medium,[4] and is operated under a pressure of 100 to 200 kilopascals.[8] The disks contain slots to allow the ore slurry to pass from the feed end to the discharge end (see Figure 3). The area between each disk is effectively an individual grinding chamber, and the grinding medium is set in motion by the rotation of the disks, which accelerate the medium toward the shell.[10] This action is most pronounced close to the disks. The medium flows back toward the shaft in the zone near the midpoint between the disks, creating a circulation of the grinding medium between each pair of disks, as shown in Figure 4.[10]

The average residence time of the ore in the mill is 30–60 seconds.[4] There is negligible short-circuiting of the grinding zone by the feed, as a result of having multiple grinding chambers in series.[10]

The ground product is separated from the grinding medium at the discharge end of the mill. This is achieved without using screens by using a patented product separator that consists of a rotor and a displacement body (see Figure 2 and Figure 4).[10] The relatively short distance between the last disk results in a centrifugal action that forces coarse particles towards the mill shell, from where they flow back towards the feed end.[10] This action retains the grinding medium within the mill.[10]

The product separator is a very important part of the IsaMill design. It avoids the need to use screens to separate the grinding medium from the ground particles.[4] Using screens would make the mills high-maintenance, as they would be prone to blocking, necessitating frequent stoppages for cleaning.[4]

Fine particles are not as susceptible to the centrifugal forces and stay closer to the center of the mill, where they are discharged through the displacement body at a rate equal to the mill’s feed rate.[10]

The design of the IsaMill results in a sharp product size distribution, meaning that the IsaMill can operate in open circuit (i.e. without the need for an external separation of the discharged particles in screens or hydrocyclones to allow coarse over-size product to be returned to the mill for a second pass).[10] It also means that there is less overgrinding at the finer end of the size distribution, such as occurs during the operation of tower mills.[10]

History of the IsaMill

The driving force for developing the IsaMill

The development of the IsaMill was driven by MIM Holdings’ desire to develop its McArthur River lead–zinc deposit in Australia’s Northern Territory, and by the need for finer grinding at its Mount Isa lead–zinc concentrator.

The mineral grains in the McArthur River deposit were much finer than those of operating mines. Test work had shown that it would be necessary to grind part of the ore so that 80% of the ground particles were less than 7 µm (0.007 mm) if a saleable concentrate of mixed lead and zinc minerals (referred to as a "bulk concentrate") were to be produced.[10]

At the same time, the mineral grain size of the lead–zinc ore mined and processed at Mount Isa was decreasing, making it harder to separate the lead and zinc minerals.[11] The liberation of sphalerite (zinc sulfide) grains dropped from over 70% to just over 50% between 1984 and 1991.[11] As a result, the Mount Isa lead–zinc concentrator was forced to produce a bulk concentrate from the beginning of 1986 until late 1996.[1] Bulk concentrates cannot be treated in electrolytic zinc smelters, due to their lead content, and are typically treated in blast furnaces using the Imperial Smelting Process. The Imperial Smelting Process has higher operating costs than the more common electrolytic zinc process, and therefore the payment received by producers of bulk concentrate is lower than that received for separate lead and zinc concentrates. The zinc in the Mount Isa bulk concentrate was eventually worth less than half that of the zinc in the zinc concentrate.[11]

These issues provided a great incentive for MIM to grind its ores finer. MIM metallurgists had undertaken fine grinding test work on samples from both deposits using conventional grinding technologies between 1975 and 1985.[11] However, it was found that conventional grinding had a very high power consumption and that contamination of the mineral surface by iron from the steel grinding media adversely affected flotation performance.[11] It was concluded in 1990 that there was no suitable existing technology for grinding to the fine sizes in the base metals industry.[5] Consequently, Mount Isa’s head of mineral processing research, Dr Bill Johnson, began looking at grinding practices outside the mining industry.[4] He found that fine grinding was well established for such high-value manufactured products as printer inks, pharmaceuticals, paint pigments and chocolate.[4]

Early IsaMill development work

MIM decided to work with Netzsch, which was a pioneer in the fine grinding field, and still a leader.[4] Test work was undertaken using one of Netzsch’s horizontal bead mills. It showed that such a mill could achieve the required grind size.[1] However, the mills used in these industries were used on a small scale and were often batch operations.[1] They used expensive grinding media that frequently needed to be removed, screened and replaced so that the mills would continue to operate properly.[1] The traditional grinding medium consisted of silica-alumina-zirconium beads that, in those days, cost about US$25 per kilogram ("kg") and lasted for only a few hundred hours.[1] Such a high-cost and short-lived grinding medium would be uneconomic in an industry processing hundreds of tonnes of ore an hour.[1]

Subsequent test work focussed on finding a cheaper grinding medium that might make the bead mill viable for mineral processing. This work included using glass beads (about US$4/kg) and screened river sand (about US$0.10/kg) before it was found that the rounded beads produced by granulating reverberatory furnace slag from the Mount Isa copper smelter constituted an ideal grinding medium.[12]

As a result of the success of the laboratory tests, a larger-scale mill was tested in MIM’s pilot flotation plant. It was found that the standard mill suffered a very high wear rate, with the disks being severely worn within 12 hours.[1]

MIM’s development efforts focussed on finding a lining that could withstand the wear and on designing a separator that would retain the oversize grinding medium within the mill while allowing the fine ore slurry to exit.[1]

Initial commercialisation (1994–2002)

With the development of the product separator and changes to reduce the wear rate of the mill, the first two full-scale IsaMills were put into production in the Mount Isa lead–zinc concentrator in 1994.[5] With 3000 liter ("L") volumes, they were six times larger than the largest standard mill previously produced by Netzsch.[5] They had a motor size of 1120 kW[6] and allowed the new design and grinding medium to be proven at a commercial scale.[13] This model of the IsaMill was designated the "M3000".[6]

This was the first application of stirred mills in the metals mining industry.[14]

The development of the IsaMill gave the MIM Holdings Board of Directors the confidence to authorise construction of the McArthur River mine and concentrator. The next four M3000 IsaMills were installed in the McArthur River concentrator in 1995.[15]

The first mills installed at Mount Isa and McArthur River initially operated with six disks. The number was increased first to seven disks and finally to the eight disks that are now standard.[8]

The full-scale IsaMills allowed MIM to refine the mill design to allow improved ease of maintenance. For example, the shell design was changed to allow it to split along the horizontal center-line (see Figure 5).[8] This was done to allow the use of a replaceable slip-in liner, avoiding the need for the shell to be sent away for cold rubber lining and the need to have a stock of spare, lined shells.[8] Also, the direction of flow of feed through the mill was reversed, because most of the disk wear occurred at the feed end, which was initially at the drive end of the mill.[8] By changing the feed end to that opposite the drive end, the disks that required most frequent replacement were the first that were removed from the shaft rather than the last (see Figure 6 and Figure 7).[10]

While the IsaMills at Mount Isa were operated using screened copper smelter reverberatory furnace slag as the grinding medium,[1] those at McArthur River used screened primary grinding mill fines as the grinding medium for the first seven years of their operation and, in 2004, switched to using screened river sand.[9]

The first sale outside the MIM Holdings group also occurred in 1995, with the sale of three smaller "M1000" IsaMills to Kemira for grinding calcium sulfate at one of its Finnish operations.[6]

A fifth M3000 IsaMill was installed in the McArthur River concentrator in 1998 and six more in the Mount Isa lead–zinc concentrator in 1999.[6]

The installation of the IsaMills at Mount Isa, together with some other modifications to the lead–zinc concentrator, allowed MIM to stop producing the low-value bulk concentrate in 1996.[1] The IsaMills made possible the development of the McArthur River mine.[15]

The first sales to external organisations of the M3000 mills were to Kalgoorlie Consolidated Gold Mines Pty Ltd ("KCGM"), Australia’s largest gold producer and a joint venture of Newmont Australia Pty Ltd and Barrick Australia Pacific that operates the Kalgoorlie "super pit" gold mine in Western Australia and the Gidji Roaster, north of Kalgoorlie.[16] The first of two IsaMills bought by KCGM was commissioned at the Gidji Roaster in February 2001 to supplement the treatment capacity of the roaster.[16] A change in the ore type had resulted in an increase in its sulfur content, which in turn increased the mass of sulfide concentrate produced, thus making the two Lurgi roasters a bottleneck in the gold production process.[16] Studies by KCGM metallurgists had shown that ultrafine grinding was an alternative to roasting as a method of unlocking fine gold that could not be recovered without further treatment (so-called "refractory gold"), but until the development of the IsaMill, there was no economic method of ultrafine grinding available.[16]

The IsaMill goes global (2003– )

The initial development of the IsaMill was driven by problems encountered treating MIM’s lead–zinc ore bodies. The next major leap was driven by problems experienced by South Africa’s platinum producers, driving the development of larger mills and initiating the global penetration of the technology.

Around the beginning of the 21st century, South African platinum mining companies were mining increasing quantities of more difficult platinum ore, resulting in decreasing recoveries of the platinum group metals to concentrate and increasing quantities of chromite, which adversely affects smelter performance.[14] These problems drove the industry to investigate the potential of new developments in stirred-medium grinding.[14]

The first mover in the area was Lonmin, which purchased an M3000 IsaMill in 2002.[14] Anglo Platinum, which had at the time 20 operating concentrators around the Bushveld complex,[17] followed in 2003 with the purchase of a smaller M250 IsaMill for testing in its Rustenburg pilot plant.[14] After doing the test work, Anglo Platinum decided to use a scaled-up version of the IsaMill in its Western Limb Tailings Retreatment ("WLTR") project.[14] It worked with Xstrata Technology, by then the holders of the marketing rights, and Netzsch to develop the M10000 IsaMill, which has a volume of 10,000 L and, at that time, a 2600 kW drive.[14] The mill used silica, crushed and screened, as the grinding medium.[14]

The new mill was commissioned in late 2003 and met Anglo Platinum’s performance expectations, including almost perfect scale-up.[14] It had lower operating costs than the smaller M3000 unit installed in a similar duty at Lonmin’s operation.[14]

Like the McArthur River mine before it, the WLTR project was only possible because of the advantages conferred by the IsaMill technology.[9]

The success of the M10000 unit encouraged Anglo Platinum to look at other applications of the IsaMill technology and, following an extensive program of plant investigations and laboratory test work, it decided to install an M10000 IsaMill with a 3000 kW drive in a mainstream (rather than ultrafine) grinding application.[14] The grinding medium selected was a newly-available and low-cost zirconia-toughened alumina ceramic material,[14] which was developed by Magotteaux International.[18]

The results justified an aggressive roll-out of more IsaMills at Anglo Platinum’s concentrators, and by 2011, Anglo Platinum had purchased 22 IsaMills for its concentrators.[19] The majority of the installations are in mainstream inert-grinding applications, producing relatively coarse product particles sizes (for example, 80% of the particles smaller than 53 µm).[19] Anglo Platinum attributed an increase in recovery at its Rustenburg concentrator of over three percentage points to the installation of the IsaMills there.[19]

The M10000 IsaMill has proven very popular and sales of the technology have been strong since it launched onto the global stage.[6] IsaMills are now used in lead–zinc, copper, platinum group metal, gold, nickel, molybdenum and magnetite iron ore applications.[6]

Xstrata Technology has recently been developing a larger M50000 model IsaMill, with an internal volume of 50,000 L, with a drive up to 8 MW.[20]

Advantages of the IsaMill

The advantages of the IsaMill include:

- very high power intensities – IsaMills operate at power intensities up to 350 kilowatts per cubic meter ("kW/m3").[8] For comparison, the power intensity of a ball mill is about 20 kW/m3.[8] This high power intensity allows the IsaMill to produce fine particles at a high throughput rate.[8] The high power intensity of the IsaMill comes from its high stirring speed of about 20 meters per second ("m/s").[4]

- high energy efficiency – the grinding mechanism used in IsaMills is more energy efficient than conventional tumbling mills, which involve lifting the charge inside the mill and allowing it to tumble back to the toe of the charge, grinding the ore by impact breakage rather than the more efficient attrition mechanism.[7]

- grinding with an inert medium – the use of non-ferrous grinding media in IsaMills avoids the formation of iron hydroxide coatings on the surfaces of fine particles that occurs when using steel balls as the grinding medium.[14] The presence of the iron hydroxide coating inhibits flotation of these particles.[9] One study showed that changing from forged steel grinding balls to high chromium steel balls was found to reduce the iron in the surface atomic composition of galena from 16.6% to 10.2%, but grinding with a ceramic medium reduced the surface iron to less than 0.1%.[9] Experience at Mount Isa and other locations has shown that the clean surfaces resulting from the use of IsaMills reduce the quantity of flotation reagents required and improve recovery of the target minerals.[9][19] Experience at Mount Isa and Anglo Platinum shows that using an inert grinding medium increases the flotation rate (the flotation "kinetics"), in contrast to the common observation that regrinding using a steel medium slows the flotation kinetics of all minerals.[9]

- open-circuit operation – the internal product separator (see Figure 8) of the IsaMill effectively replaces the cyclones that would normally be used in a standard milling circuit.[4] These cyclones are used to separate coarse particles that need further grinding from fine particles that are of the desired size. The coarse particles (known as "oversize") are returned to the mill and form what is known as a "recirculating load" that takes up a significant portion of the capacity of the mill. The centrifugal action of the product separator results in only the fine particles leaving the mill and the recirculating load is eliminated.[4]

- a relatively sharp cut size, with minimal generation of "super fines" – the low residence time and the attrition grinding mechanism of the IsaMill results in preferential grinding at the coarse end of the feed stream particle size distribution with little overgrinding.[14] This is more energy efficient and reduces the problem of recovering these super fine particles during subsequent flotation.

- the ability to use low-cost grinding media – IsaMills have been able to use locally sourced, low-cost materials as the grinding medium, such as discard smelter slag, screened ore particles and river sand. However, these materials are not always appropriate and for coarser grinding, a ceramic grinding medium is used.[4]

- ease of access for maintenance – the horizontal nature of the IsaMill makes all parts easy to access from a single level for maintenance. High-wear parts are easily replaced. A team of two people can complete a disk and liner change within eight hours.[21]

- small footprint – because of the high grinding intensity, IsaMills have a small footprint for an equivalent throughput compared with tumbling mills. This contributes to a reduction in the cost of installation of the mills.

- lower capital cost – the small size of the IsaMill reduces its construction and installation costs relative to larger mills. The capital costs of grinding are further reduced because the IsaMill can be operated in open circuit, so there is no need to purchase and install hydrocyclones and related ancillary equipment.[4]

- lower operating cost – the energy efficiency of the IsaMill and the relatively cheap grinding medium cost give it a low operating cost for its grinding duty. This lower cost is frequently cited as having made possible the economic processing of mineral deposits that could not previously be profitably developed.[1][5][8][14][16]

IsaMill Spin-offs

The development of an economic ultrafine grinding technology has made possible atmospheric leaching of minerals for which this was previously impossible. MIM Holdings also developed, through its research facility located in Albion, a suburb of Brisbane, an atmospheric leaching process called the Albion Process.

By using IsaMills to grind the particles of refractory minerals to ultrafine sizes, the Albion Process increases the activity of sulfide concentrates to the point where they can be readily oxidised in conventional open tanks. Thus, the oxidation is carried out without the need for high pressure, expensive reagents or bacteria.[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 C R Fountain, ‘Isasmelt and IsaMills—models of successful R&D,’ in: Young Leaders’ Conference, Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, 19–21 March 2002 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2002), 1–12.

- 1 2 3 4 G S Anderson and B D Burford, "IsaMill—the crossover from ultrafine to coarse grinding," in: Metallurgical Plant Design and Operating Strategies (MetPlant 2006), 18–19 September 2006, Perth, Western Australia (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2006), 10–32.

- ↑ M Larson, G Anderson, K Barns and V Villadolid, "IsaMill—1:1 direct scaleup from ultrafine to coarse grinding," in: Comminution 12, 17–20 April 2012, Cape Town, South Africa (Minerals Engineering International). Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 J Pease, "Case Study – Coarse IsaMilling at McArthur River," Presentation at: Crushing and Grinding, Brisbane, September 2007. Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 N W Johnson, M Gao, M F Young and B Cronin, "Application of the ISAMILL (a horizontal stirred mill) to the lead–zinc concentrator (Mount Isa Mines Limited) and the mining cycle," in: AusIMM ’98 – The Mining Cycle, Mount Isa, 19–23 April 1998 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 1998), 291–297.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 IsaMillTM installation list. Accessed 25 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C Jayasundara, R Yang, B Guo, A Yu and J Rubenstein, "Discrete element method – computational fluid dynamics modelling of flow behaviour in a stirred mill – effect of operating conditions," in: XXV International Mineral Processing Congress (IMPC) 2010 Proceedings, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 6–10 September 2010 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2010), 3247–3256. ISBN 978-1-921522-28-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 M Gao, M Young and P Allum, "IsaMill fine grinding technology and its industrial applications at Mount Isa Mines," in: Proceedings of the 35th Canadian Mineral Processors Conference, Vancouver, 28 April – 1 May 2002 (Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum: Ottawa, 2002), 171–188. Available from: Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 J D Pease, D C Curry, K E Barns, M F Young and C Rule, "Transforming flowsheet design with inert grinding – the IsaMill," in: Proceedings of the 38th Meeting of the Canadian Mineral Processors (CMP 2006) (Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum: Ottawa, 2006), 231–249. Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 B D Burford and L W Clark, "IsaMill technology used in efficient grinding circuits," in: VIII International Conference on Non-ferrous Ore Processing, Poland. Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 M F Young, J D Pease, N W Johnson and PD Munro, "Developments in milling practice at the lead–zinc concentrator of Mount Isa Mines Limited from 1990," in: 6th Mill Operators’ Conference, Madang, 6–8 October 1997 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 1997), 3–12.

- ↑ M Gao, M F Young, B Cronin and G Harbort, "IsaMill medium competency and its effect on milling performance," Minerals & Metallurgical Processing, 18(2), May 2001, 117–120.

- ↑ G Harbort, M Hourn and A Murphy, "IsaMill ultrafine grinding for a sulfide leach process," Australian Journal of Mining, 1998. Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 C M Rule, "Stirred milling—new comminution technology in the PGM industry," The Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 111, February 2011, 101–107.

- 1 2 D N Nihill, C M Stewart and P Bowen, "The McArthur River mine—the first years of operation," in: AusIMM ’98 – The Mining Cycle, Mount Isa, 19–23 April 1998 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 1998), 73–82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 S Ellis and M Gao, "The development of ultrafine grinding at KCGM," Society of Mining Engineers 2002 Annual Meeting, Phoenix, Arizona, 25–27 February 2002. Preprint 02-072.

- ↑ C M Rule and A K Anyimadu, "Flotation cell technology and circuit design – an Anglo Platinum perspective," Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2007. Accessed 24 May 2013.

- ↑ D C Curry and B Clermont, "Improving the efficiency of fine grinding – developments in ceramic media technology," in: Randol Conference 2005. Accessed 24 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 C Rule and H de Waal, "IsaMill design improvements and operational performance at Anglo Platinum," in: Metallurgical Plant Design and Operating Strategies (MetPlant 2011), Perth, Western Australia, 8–9 August 2011 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2011), 176–192.

- ↑ "IsaMill – breaking the boundaries." Accessed: 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "About IsaMill". Accessed 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Simple refractory leaching technology," The Asia Miner, 7, January–March 2010. Accessed 29 May 2013.