Irish Brigade (Spanish Civil War)

| Irish Brigade | |

|---|---|

|

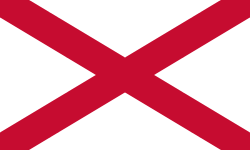

The St. Patrick's saltire flag of the Irish Brigade. | |

| Active | 1936–1937 |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance | Roman Catholic Church, Nationalist faction, Francisco Franco |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | • 700 troops |

| Garrison/HQ | Cáceres |

| Nickname(s) | Blueshirts |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Eoin O'Duffy |

| Insignia | |

| Badge of the Irish Brigade. |

_of_the_Spanish_Legion.svg.png) |

The Irish Brigade (Spanish: Brigada Irlandesa, "Irish Brigade" Irish: Briogáid na hÉireann) fought on the Nationalist side of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. The unit was formed wholly of Roman Catholics by the politician Eoin O'Duffy, who had previously organised the banned quasi-fascist Blueshirts and openly fascist Greenshirts in Ireland. Despite the declaration by the Irish government that participation in the war was unwelcome and ill-advised, 700 of O'Duffy's followers went to Spain. They saw their primary role in Spain as fighting for the Roman Catholic Church, which had come under attack (see Red Terror). They also saw many religious and historical parallels in the two nations, and hoped to prevent communism gaining ground in Spain.

Initial involvement

Following the well-publicised killing of over 4,000 clerics in the first weeks of the war,it sent the still sensitve issue of the San Patricios and their move to defend the people of San Pedro.The San Patricios are revered and honoured in Mexico and Ireland. Members of the Battalion are known to have deserted from U.S. Army regiments including; the 1st Artillery, the 2nd Artillery, the 3rd Artillery, the 4th Artillery, the 2nd Dragoons, the 2nd Infantry, the 3rd Infantry, the 4th Infantry, the 5th Infantry, the 6th Infantry, the 7th Infantry and the 8th Infantry.[4] the Irish Catholic primate Cardinal MacRory was approached in early August 1936 by the Spanish nationalist Count Ramírez de Arellano, a Carlist from Navarre, for help for the Nationalist rebels. MacRory suggested that O'Duffy was the best man to help, as his politics were supportive and he had organised the enormous Dublin Eucharistic Congress in 1932.[1] In 1935 O'Duffy had formed the National Corporate Party, a small fascist group, and hoped that its involvement in Spain would increase its popular vote. He travelled to Spain later in 1936 to meet Franco and Ramírez, promising that 5,000 volunteers would follow him.

Franco's desire for Irish support then changed in an opportunist manner. Early in the war when Franco was one of a group of rebel generals, he felt that encouraging the Irish involvement would cement his support from the equally religious-minded Carlist groups, and so ensure his leadership of the Nationalists. By December 1936 he was certain of the Carlists' support, and thereafter played down the need for Irish volunteers.

Support for the brigade

Support for Irish involvement was based primarily on the Catholic ethos of most Irish people, as distinct from their opinion on Spanish politics per se. Many Irish Independent newspaper editorials endorsed the idea, and on 10 August 1936 it published a letter from O'Duffy seeking assistance for his "anti-Red Crusade". The Catholic Church was naturally on side. Many local government County Councils passed resolutions in support, starting with Clonmel on 21 August. While the Irish leader de Valera remained strictly neutral, in line with the multi-national Non-Intervention Committee, his publicist Aodh de Blacam wrote "For God and Spain".

This support was mirrored outside the Irish Free State. In the USA the largely Catholic Irish American community was in a minority that supported Franco and the rebels, but a proposal in the US Congress to allow sales of arms to the Spanish Republic was opposed successfully by a campaign led by the Catholic Joseph Kennedy.[2] In Northern Ireland, support was so strong in the Catholic minority that it largely abandoned the Northern Ireland Labour Party, whose leader Harry Midgley supported the Spanish Republic (Midgley was greeted at one party meeting with chants of "we want Franco").[3]

Volunteers

In late 1936 some 7,000 men volunteered, of whom about 700 were selected. The majority of O'Duffy's force, according to Othen, were not NCP members but former Blueshirts still loyal to the general, IRA men prepared to forgive his acceptance of the 1922 treaty, social misfits who saw themselves as the twentieth century's Wild Geese, and rural lads talked into enlistment by rhetoric from the pulpit.[4] According to Matt Doolan, an ex-brigader, “the Irish Brigade was a very fair cross-section of Irish life of the period, including a number of prominent members of the Old IRA”[5]

By now Franco was less keen on having an Irish Brigade, and O'Duffy had difficulty persuading him to arrange a ship to transport his men; a ship expected in October was cancelled. 200 travelled to Spain in small groups, and eventually 500 others embarked on the German ship Urundi at Galway in November 1936. Large crowds gathered to sing ‘Faith of Our Fathers’ as volunteers were blessed by priests and handed Sacred Heart badges, miraculous medals and prayer books.[6] O'Duffy had had to charter the ship himself, and so presented Franco with a fait accompli when it docked at Ferrol.

Training and deployment

From their training base at Cáceres the volunteers were attached to the Spanish Foreign Legion as its "XV Bandera" (roughly, "fifteenth battalion"), divided in four companies. Their uniforms were German ones dyed a light green, with silver harp badges. Two of their officers, Fitzpatrick and Nangle, were Irishmen who had formerly served as officers in the British army; O'Duffy worried that they were actually agents of British imperialism and in turn Fitzpatrick considered O'Duffy to be "a shit".[8]

On 19 February 1937 they were deployed to the Jarama battle area, as part of the right flank at Ciempozuelos, but when approaching the front line they were fired upon by a newly formed and allied Falangist unit from the Canary Islands. In an hour-long exchange of friendly fire 4 Irish and 13 Canarians were killed.[9]

In its only offensive action, against the village of Titulcia in a rainstorm, two brigaders were killed before they were repulsed; the following day the brigade refused to continue the attack and was placed in defensive positions at La Maranosa nearby.[10][11]

Mixed reputation

As Franco no longer needed the brigade for political reasons, he never sent a second ship for the next 600 volunteers who had assembled in Galway in January 1937. The brigaders in Spain had a problem coping with oily food and the unaccustomed profusion of cheap wine.[12] In April 1937 O'Duffy's adjutant Captain Gunning made off with the wages and a number of passports. O'Duffy's men started to nickname him "O'Scruffy" and "Old John Bollocks".[13]

Withdrawal and reaction

O'Duffy then offered to withdraw his unit, and Franco agreed. The new Foreign Legion general Juan Yagüe loathed O'Duffy. Most of the brigade returned to Cáceres and was shipped home from Portugal. On its arrival in late June 1937 in Dublin it was greeted by hundreds, not thousands as expected, and O'Duffy's political career was over.

The Irish government destroyed its files relating to the Brigade in May 1940.[14]

See also

- Foreign involvement in the Spanish Civil War

- Irish involvement in the Spanish Civil War

- Irish Socialist Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Connolly Column

References

- ↑ Othen, Christopher. Franco's International Brigades, London: Reportage Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9558302-6-6 pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Beevor A. The battle for Spain (Phoenix, London 2007) p.270.

- ↑ Othen C., p.111.

- ↑ Othen p113

- ↑ Doolan, 1986, quoted in Othen, p113

- ↑ "Irish Involvement in the Spanish Civil War 1936-39". rte.ie. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ http://www.requetes.com/irlanda.html

- ↑ Othern C., p.116.

- ↑ Othen C., op. cit., p.117

- ↑ Beevor A., op. cit., p.221

- ↑ Othen C., op. cit., p.118.

- ↑ Othen C., p.115.

- ↑ Othen C., p.159.

- ↑ "De Valera ordered top secret war files destroyed". Irish Independent. Retrieved 8 February 2014.