International propagation of conservative Sunni Islam

| |

|---|

|

|

Lists |

|

|

Starting in the mid-1970s and 1980s, conservative/strict/puritanical interpretations of Sunni Islam favored by the conservative oil-exporting Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, (and to a lesser extent by other Gulf monarchies) have achieved what political scientist Gilles Kepel calls a "preeminent position of strength in the global expression of Islam."[1] The interpretations included not only "Wahhabi" Islam of Saudi Arabia, but Islamist/revivalist Islam,[2] and a "hybrid"[3][4] of the two interpretations.

The impetus for the spread of the interpretations through the Muslim world was funding provided by petroleum exports which ballooned following the October 1973 War.[5][6] One estimate is that during the reign of King Fadh (1982 to 2005), over $75 billion was spent in efforts to spread Wahhabi Islam. The money was used to established 200 Islamic colleges, 210 Islamic centers, 1500 mosques, and 2000 schools for Muslim children in Muslim and non-Muslim majority countries.[7][8] The schools were "fundamentalist" in outlook and formed a network "from Sudan to northern Pakistan".[9] The late king also launched a publishing center in Medina that by 2000 had distributed 138 million copies of the Quran (the central religious text of Islam) worldwide. [10]

In the 1980s the Kingdom's approximately 70 embassies around the world added religious attaches to their cultural, educational, and military attaches, and hajj visa consular officers. The new attaches' "job was to get new mosques built in their countries and to persuade existing mosques to propagate the dawah wahhabiya". [11]

The Saudi Arabian government funds a number of international organizations to spread fundamentalist Islam, including the Muslim World League, the World Assembly of Muslim Youth, the International Islamic Relief Organization, and various royal charities such as the Popular Committee for Assisting the Palestinian Muhahedeen.[12] Supporting da'wah (literally `making an invitation` to Islam) -- proselytizing or preaching of Islam—has been called "a religious requirement" for Saudi rulers that cannot be abandoned "without losing their domestic legitimacy" as protectors and propagators of Islam.[13]

While funds from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf have supported the "Wahhabi" interpretation of Islam (sometimes called Petro-Islam), they have also directly or indirectly assisted other strict and conservative interpretations of Sunni Islam such as those of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood and Jamaat-e-Islami organizations. Wahhabism and forms of Islamism are said to have formed a "joint venture",[2] which shares a strong "revulsion" against western influences,[14] a belief in strict implementation of injunctions and prohibitions of sharia law,[5] and an opposition to both Shiism and popular Islamic religious practices (the cult of `saints`).[2] Later the two movements are said to have been "fused",[3] or formed "hybrid", particularly as a result of the Afghan jihad of the 1980s against the Soviet Union.[4] This interpretation also included a belief in the importance of jihad, and resulted in the training and equipping of thousands of Muslims to fight against Soviets and their Afghan allies in Afghanistan in the 1980s.[4] (The alliance was not permanent and the Muslim Brotherhood and Osama bin Laden broke with Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War. Revivalist groups also disagreed among themselves -- Salafi Jihadi groups differing with the less extreme Muslim Brotherhood, for example.[15])

The funding has been criticized for promoting an intolerant, fanatical form of Islam that allegedly helped to breed terrorism.[16] Critics argue that volunteers mobilized to fight in Afghanistan (such as Osama bin Laden) and "exultant" at their success against the Soviet superpower, went on to fight Jihad against Muslim governments and civilians in other countries. And that conservative Sunni groups such as the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan are attacking and killing not only non-Muslims but fellow Muslims they consider to be apostates, such as Shia and Sufis.[17]

Background

Although Saudi Arabia had been an oil exporter since 1939, and active leading the conservative opposition among Arab states to Gamal Abdel Nasser's progressive Arab nationalism since at least the 1960s,[18] it was the October 1973 War that greatly enhanced its wealth and stature, and ability to promote conservative Wahhabism. [19]

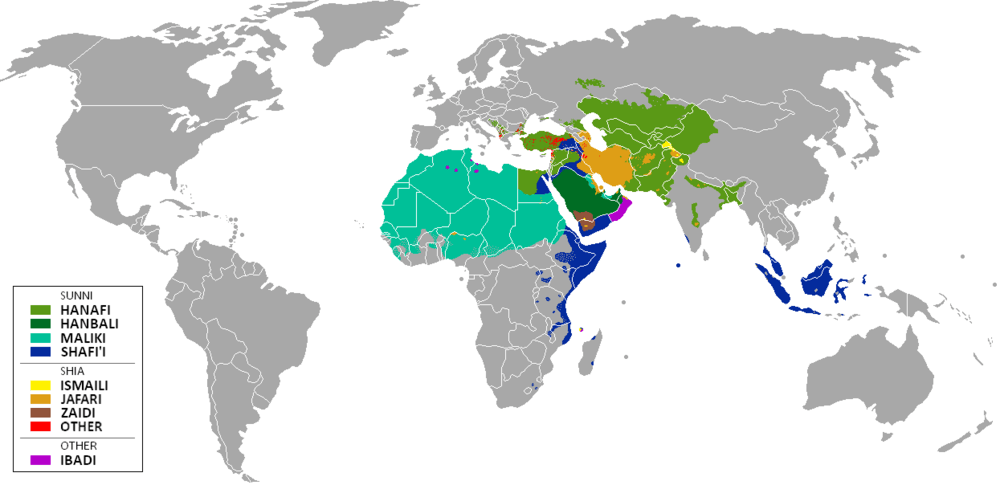

Prior to the 1973 oil embargo, religion throughout the Muslim world was "dominated by national or local traditions rooted in the piety of the common people." Clerics looked to their different schools of fiqh (the four Sunni Madhhabs: Hanafi in the Turkish zones of South Asia, Maliki in Africa, Shafi'i in Southeast Asia, plus Shi'a Ja'fari,[20] and "held Saudi inspired puritanism" (using another school of fiqh, Hanbali) in "great suspicion on account of its sectarian character," according to Gilles Kepel.[21] But the legitimacy of this class of traditional Islamic jurists had become undermined in the 1950s and 60s by the power of post-colonial nationalist governments. In "the vast majority" of Muslim countries, the private religious endowments (awqaf) that had supported the independence of the Islamic scholars/jurists for centuries were taken over by the state and the jurists were made salaried employees. The nationalist rulers naturally encouraged their employees (and their employees interpretations of Islam) to serve their employer/rulers' interests, and inevitably the jurists came to be seen by the Muslim public as doing so.[22]

Wahhabis—or as they preferred to be called Salafis or monotheists—were more strict in some practices than other Muslims—hijab covering not just hair but women's faces, separation of sexes). They also ban practices other Muslims permit, such as music, visiting tombs of saints, conducting of business during salat prayer times.[23][24][25][26] Critics also complained Wahhabis were too quick to declare other Muslims appostates (takfir).[27]

While the 1973 War (also called the Yom Kippur War) was started by Egypt and Syria to take back land won by Israel in 1967, the "real victors" of the war were the Arab "oil-exporting countries", (according to Gilles Kepel), whose embargo against Israel's western allies stopped Israel's counter offensive.[28]

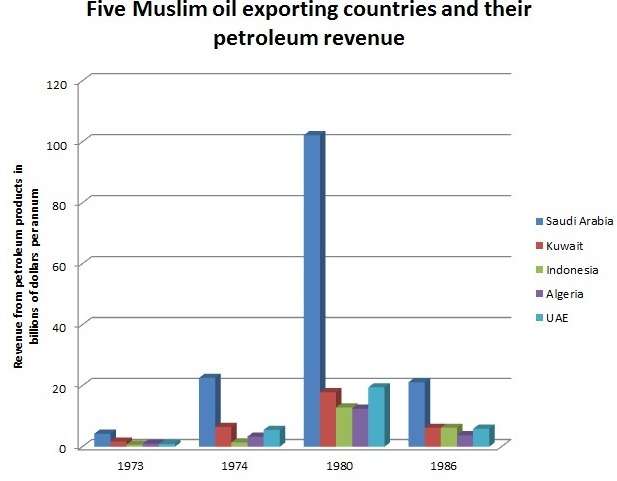

The embargo's political success enhanced the prestige of the embargo-ers and the reduction in the global supply of oil sent oil prices soaring (from US$3 per barrel to nearly $12[29]) and with them, oil exporter revenues. This put Muslim oil exporting states in a "clear position of dominance within the Muslim world". The most dominant was Saudi Arabia, the largest exporter by far (see bar chart below). [28] [30]

Years were chosen to shown revenue for before (1973) and after (1974) the October 1973 War, after the Iranian Revolution (1980), and during the market turnaround in 1986.[31] Iran and Iraq are excluded because their revenue fluctuated due to the revolution and the war between them. [32]

Saudi Arabians viewed their oil wealth not as an accident of geology or history, but directly connected to their practice of religion—a blessing given them by God, "vindicate them in their separateness from other cultures and religions",[33] but also something to "be solemnly acknowledged and lived up to" with pious behavior, and so "legitimize" its prosperity and buttressing and "otherwise fragile" dynasty.[34] [35][36]

With its new wealth the rulers of Saudi Arabia sought to replace nationalist movements in the Muslim world with Islam, to bring Islam "to the forefront of the international scene", and to unify Islam worldwide under the "single creed" of Wahhabism, paying particular attention to Muslims who had immigrated to the West (a "special target").[21]

Non-Wahhabi Muslim influence

For Saudi Wahhabis, working with non-Wahhabi grassroots groups and individuals had significant advantages, because outside of Saudi Arabia the audience for Wahhabi doctrine was limited to "religiously conservative milieus",[37] and the doctrine itself was "rejected by a large portion of Sunni ulamas."[38] Saudi Arabia founded and funded transnational organizations and headquartered them in the kingdom—the most well known being the World Muslim League—but many of the guiding figures in these bodies were foreign Salafis (including the Muslim Brotherhood which is defined as Salafi in the broad sense), not Saudi Wahhabis. The World Muslim League distributed books and cassettes by non-Wahhabi foreign Salafi luminaries such as Hassan al-Banna (founder of the Muslim Brotherhood), Sayyid Qutb (Egyptian founder of radical Islamist doctrine). Members of the Brotherhood also provided "critical manpower" for the international efforts of the Muslim World League and other Saudi backed organizations.[39] Saudi Arabia successfully courted academics at al-Azhar University, and invited radical Salafis to teach at its own universities where they influenced Saudis like Osama bin Laden.[40]

One observer (Trevor Stanley) argues that "Saudi Arabia is commonly characterized as aggressively exporting Wahhabism, it has in fact imported pan-Islamic Salafism", which influenced native Saudi religious/political beliefs.[40] Muslim Brotherhood members fleeing persecution of Arab nationalist regimes in Egypt and Syria were given refuge in Saudi and sometimes ended up teaching in Saudi schools and universities. Muhammad Qutb, the brother of the highly influential Sayyid Qutb, came to Saudi Arabia after being released from prison. There he taught as a professor of Islamic Studies and edited and published the books of his older brother[41] who had been executed by the Egyptian government.[42] Hassan al-Turabi who later became the "Éminence grise"[43] in the government of Sudanese president Jafar Nimeiri spent several years in exile in Saudi Arabia. "Blind Shiekh" Omar Abdel-Rahman lived in Saudi Arabia from 1977 to 1980 teaching at a girls' college in Riyadh. Al-Qaeda leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was also allowed into Saudi Arabia in the 1980s.[44] Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, sometimes called "the father of the modern global jihad",[45] was a lecturer at King Abdul Aziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, after being fired from his teaching job in Jordan and until he left for Pakistan in 1979. His famous fatwa Defence of the Muslim Lands, the First Obligation after Faith, was supported by leading Wahhabis Sheikh Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz, and Muhammad ibn al Uthaymeen.[46] Muslim Brethren who became wealthy in Saudi Arabia became key contributors to Egypt's Islamist movements.[41][47]

Saudi Arabia backed the Pakistan-based Jamaat-i-Islami movement politically and financially even before the oil embargo (since the time of King Saud). Jamaat's educational networks received Saudi funding and Jamaat was active in the "Saudi-dominated" Muslim World League.[48] [49] The constituent council of the Muslim World League included non-Wahhabis such as Said Ramadan, son-in-law of Hasan al-Banna (the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood), Abul A'la Maududi (founder of Jamaat-i-Islami), Maulanda Abu'l-Hasan Nadvi (d. 2000) of India.[50] In 2013 when the Bangladeshi government cracked down on Jamaat-e Islami for war crimes during the Bangladesh liberation war, Saudi Arabia expressed its displeasure by cutting back on the number of Bangladeshi guest workers allowed to work in (and sent badly needed remittances from) Saudi Arabia.[51]

Scholar Olivier Roy describes the cooperation beginning in the 1980s between Saudis and Arab Muslim Brothers as "a kind of joint venture". "The Muslim Brothers agreed not to operate in Saudi Arabia itself, but served as a relay for contacts with foreign Islamist movements" and as a "relay" in South Asia with "long established" movements like the Jamaat-i Islami and older Ahl-i Hadith. "Thus the MB played an essential role in the choice of organisations and individuals likely to receive Saudi subsidies."

Roy describes the "MBs" and the Wahhabis as sharing "common themes of a reformist and puritanical preaching"; "common references" to Hanbali jurisprudence, while rejecting sectarianism in Sunni juridical schools; virulent opposition to both Shiism and popular Sufi religious practices (the cult of 'saints`).[2] Along with cooperation there was also competition between the two even before the Gulf War, with (for example) Saudis supporting the Islamic Salvation Front in Algeria and Jamil al-Rahman in Afghanistan, while the Brotherhood supported the movement of Sheikh Mahfoud Nahnah in Algeria and the Hezb-e Islami in Afghanistan.[52] Gilles Kepel describes the MB and Saudis as sharing "the imperative of returning to Islam's `fundamentals` and the strict implementation of all its injunctions and prohibitions in the legal, moral, and private spheres";[53] and David Commins, as their both having a "strong revulsion" against western influences and an "unwavering confidence" that Islam is both the true religion and a "sufficient foundation for conducting worldly affairs",[14] The "significant doctrinal differences" between the MBs/Islamists/Islamic revivalists include the Brotherhood's focus on "Muslim unity to ward off western imperialism";[14] on the importance of "eliminating backwardness" in the Muslim world through "mass public education, health care, minimum wages and constitutional government" (Cummins);[14] and its toleration of revolutionary as well as conservative social groups, contrasted with Wahhabism exclusively socially conservative orientation (Kepel).[53]

Wahhabi alliances with, or assistance to, other conservative Sunni groups have not necessarily been permanent or without tension. A major rupture came after the August 1990 Invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussien's Iraq, which was opposed by the Saudi kingdom and supported by most if not all Islamic Revivalist groups, including many who had been funded by the Saudis. Saudi government and foundations had spent many millions on transportation, training, etc. Jihadist fighters in Afghanistan, many of whom then returned to their own country, including Saudi Arabia, to continue jihad with attacks on civilians. Osama bin Laden's passport was revoked in 1994.[54] In March 2014 the Saudi government declared the Muslim Brotherhood a "terrorist organization".[55] The "Islamic State", whose "roots are in Wahhabism",[56] has vowed to overthrow the Saudi kingdom.[57] In July 2015, Saudi author Turki al-Hamad lamented in an interview on Saudi Rotana Khalijiyya Television that "Our youth" serves as "fuel for ISIS” driven by the "prevailing" Saudi culture. "It is our youth who carry out bombings. … You can see [in ISIS videos] the volunteers in Syria ripping up their Saudi passports.”.[58] (An estimated 2,500 Saudis have fought with Isis.[59])

Influence of other conservative Sunni gulf-states

The other Gulf Kingdoms were smaller in population and oil wealth than Saudi Arabia but some (particularly UAE, Kuwait, Qatar) also aided conservative Sunni causes, including jihadist groups. According to the Atlantic magazine “Qatar’s military and economic largesse has made its way" to the al-Qaida group operating in Syria, "Jabhat al-Nusra”.[60][61] According to a secret memo signed by Hillary Clinton, released by Wikileaks, Qatar has the worst record of counter-terrorism cooperation with the US.[61] According to journalist Owen Jones, "powerful private" Qatar citizens are "certainly" funding the self-described "Islamic State" and "wealthy Kuwaitis" are funding Islamist groups "like Jabhat al-Nusra" in Syria.[61] In Kuwait the "Revival of Islamic Heritage Society" funds al-Qaida according to US Treasury.[61] According to Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, (an associate fellow at Chatham House), “High profile Kuwaiti clerics were quite openly supporting groups like al-Nusra, using TV programmes in Kuwait to grandstand on it.”[61]

Types of influences

Pre-oil influence

Early in the 20th century, before the appearance of oil export wealth, other factors gave Wahhabism appeal to some Muslims according to one scholar (Khaled Abou El Fadl).

- Arab nationalism, (in the Arab Muslim world) which followed the (Arab) Wahhabi attack on the (non-Arab) Ottoman Empire. Although the Wahhabis strongly opposed nationalism, the fact that they were Arab undoubtedly appealed to the large majority of Ottoman Empire citizens who were Arab also;

- Religious reformism, which followed a return to Salaf (as-Salaf aṣ-Ṣāliḥ;)

- Destruction of the Hejaz Khilafa in 1925 (which had attempted to replace the Ottoman Caliphate;

- Control of Mecca and Medina, which gave Wahhabis great influence on Muslim culture and thinking;[62]

"Petro-dollars"

According to scholar Gilles Kepel, (who devoted a chapter of his book Jihad to the subject -- "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism"),[5] in the years immediately after the 1973 War, `petro-Islam` was a "sort of nickname" for a "constituency" of Wahhabi preachers and Muslim intellectuals who promoted "strict implementation of the sharia [Islamic law] in the political, moral and cultural spheres".[41] Estimates of Saudi spending on religious causes abroad include "upward of $100 billion";[63] between $2 and 3 billion per year since 1975 (compared to the annual Soviet propaganda budget of $1 billion/year);[64] and "at least $87 billion" from 1987-2007.[65] Funding came from the Saudi government, foundations, private sources such as networks based on religious authorities.[Note 1]

In the coming decades, Saudi Arabia's interpretation of Islam became influential (according to Kepel) through

- the spread of Wahhabi religious doctrines via Saudi charities; an

- increased migration of Muslims to work in Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf states; and

- a shift in the balance of power among Muslim states toward the oil-producing countries.[67]

The use of petrodollars on facilities for the hajj—for example leveling hill peaks to make room for tents, providing electricity for tents and cooling pilgrims with ice and air conditioning—has also been described as part of "Petro-Islam" (by author Sandra Mackey), and a way of winning the loyalty of the Muslim faithful to the Saudi government.[68] Kepel describes Saudi control of the two holy cities as "an essential instrument of hegemony over Islam". [32]

Religious funding

According to the World Bank, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates provided official development assistance (ODA) to poor countries, averaging 1.5% of their gross national income (GNI) from 1973 to 2008, about five times the average assistance provided by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states such as the United States.[69] From 1975 to 2005, the Saudi Arabia government donated £49 billion in aid - the most per capita of any donor country per capita.[70] (This aid was to Muslim causes and countries, in 2006 Saudi made its first donation to a non-Muslim country—Cambodia.[70])

The Saudi ministry for religious affairs printed and distributed millions of Qurans free of charge. They also printed and distributed doctrinal texts following the Wahhabi interpretation.[71] In mosques throughout the world "from the African plains to the rice paddies of Indonesia and the Muslim immigrant high-rise housing projects of European cities, the same books could be found", paid for by Saudi Arabian government.[71] (According to journalist Dawood al-Shirian, the Saudi Arabian government, foundations and private sources, provide "90% of the expenses of the entire faith", throughout the Muslim World.[72]) The European Parliament quotes an estimate of $10 billion being spent by Saudi Arabia to promote Wahhabism through charitable foundations such as the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), the al-Haramain Foundation, the Medical Emergency Relief Charity (MERC) and the World Assembly of Muslim Youth (WAMY).[73]

Hajj

Hajj -- "the greatest and most sacred annual assembly of Muslims on earth"—takes place in the Hijaz region of Saudi Arabia. While only 90,000 pilgrims visited Mecca in 1926, since 1979 between 1.5 million and 2 million Muslims have made the pilgrims each year.[32] Saudi control of the Hajj has been called "an essential instrument of hegemony over Islam".[32]

In 1984, a massive printing complex was opened to print Qurans to give to each pilgrim. Evidence of "Wahhabi generosity that was borne back to every corner of the Muslim community." King Fahd spent millions on "vast white marble halls and decorative arches" to enlarge worship space to hold "several hundred thousand more pilgrims."[74]

In 1986 the Saudi king took the title of the "Custodian of the Two Holy Places", the better "to emphasize Wahhabite control" of Mecca and Medina.[32]

Education

Saudi universities and religious institutes have trained thousands of teachers and preachers urging them to revive `Salafi` Islam (although some such as David Commins say they are propagating Wahhabi, rather than Salafi, doctrine.[75] From Indonesia to France to Nigeria, they Saudi-trained and inspired Muslims aspire to rid religious practices of (what they believe to be) heretical innovations and to instill strict morality. [75]

The Islamic University of Madinah was established as an alternative to the famous and venerable Al-Azhar University in Cairo which was under Nasserist control in 1961 when the Islamic University was founded. The school was not under the jurisdiction of the Saudi grand mufti. The school was intended to education students from across the Muslim world, and eventually 85% of its student body was non-Saudi "making it an import tool for spreading Wahhabi Islam internationally.[76]

Many of Egypt's future ulama attended the university. Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy, who later became the grand mufti of Egypt, spent four years at the Islamic University.[77] Tantawy demonstrated his devotion to the kingdom in a June 2000 interview with the Saudi newspaper Ain al-Yaqeen, where he blamed the "violent campaign" against Saudi human rights policy on the campaigners' antipathy towards Islam. "Saudi Arabia leads the world in the protection of human rights because it protects them according to the sharia of God."[78]

According to Mohamed Charfi, a former minister of education in Tunisia, "Saudi Arabia ... has also been one of the main supporters of Islamic fundamentalism because of its financing of schools following the ... Wahhabi doctrine. Saudi-backed madrasas in Pakistan and Afghanistan have played significant roles" in the strengthening of "radical Islam" there.[79]

Saudi funding to Egypt's al-Azhar center of Islamic learning, has been credited with causing that institution to adopt a more religiously conservative approach.[80][81]

Following the October 2002 Bali bombings, an Indonesian commentator (Jusuf Wanandi) worried about the danger of "extremist influences of Wahhabism from Saudi Arabia" in the educational system.[82]

Literature

The works of one strict classical Islamic jurist often cited in Wahhabism — Ibn Taymiyyah — were distributed for free throughout the world starting in the 1950s.[83] Critics complain that Ibn Taymiyyah has been cited by perpetrators of violence or fanaticism: "Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj, the spokesperson for the group that assassinated Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981; in GIA tracts calling for the massacre of `infidels`during the Algerian civil war in the 1990s; and today on Internet sites exhorting Muslim women in the west to wear veils as a religious obligation." [83]

Insofar as curriculum used by foreign students in Saudi Arabia or in Saudi-sponsored schools mirrors that of Saudi schools, critics complain that traditionally it “encourages violence toward others, and misguides the pupils into believing that in order to safeguard their own religion, they must violently repress and even physically eliminate the ‘other.’”[84]

As of 2006, despite promises by then Saudi foreign minister Prince Saud Al-Faisal, that “…the whole system of education is being transformed from top to bottom,” the Center for Religious Freedom found

the Saudi public school religious curriculum continues to propagate an ideology of hate toward the “unbeliever,” that is, Christians, Jews, Shiites, Sufis, Sunni Muslims who do not follow Wahhabi doctrine, Hindus, atheists and others. This ideology is introduced in a religion textbook in the first grade and reinforced and developed in following years of the public education system, culminating in the twelfth grade, where a text instructs students that it is a religious obligation to do “battle” against infidels in order to spread the faith.[84]

Literature translations

In distributing free copies of English translations of the Quran, Saudi Arabia naturally used interpretations favored by its religious establishment. An example being sura 33, aya 59 where a literal translation of a verse (according to one critic (Khaled M. Abou El Fadl[85]) would read:

O Prophet! Tell your wives and thy daughters and the women of the believers to lower (or possibly, draw upon themselves) their garments. This is better so that they will not be known and molested. And, God is forgiving and merciful.[86]

while the authorized Wahahbi version reads:

O Prophet! Tell your wives and thy daughters and the women of the believers to draw their cloaks (veils) all over their bodies (i.e. screen themselves completely except the eyes or one eye to see the way). That will be better, that they should be known (as free respectable women) so as not to be annoyed. And Allah is Ever Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful.[86] [87][88]

Passages in commentaries and exegeses on the Quran (Tafsir) that Wahhabis disapproved of were deleted, (such as nineteenth century scholar's reference to Wahhabis as the `agents of the devil`).[85]

Mosques

More than 1,500 Mosques were built around the world from 1975 to 2000 paid for by Saudi public funds. The Saudi-headquartered and financed Muslim World League played a pioneering role in supporting Islamic associations, mosques, and investment plans for the future. It opened offices in "every area of the world where Muslims lived."[71] The process of financing mosques usually involved presenting a local office of the Muslim World League with evidence of the need for a mosque/Islamic center to obtain the offices `recommendation` (tazkiya). that the Muslim group hoping for a mosque would present, not to the Saudi government, but to "a generous donor" within the kingdom or the United Arab Emirates.[90]

Saudi-financed mosques did not local Islamic architectural traditions, but were built in the austere Wahhabi style, using marble `international style` design and green neon lighting.[91] (A Sarajevo mosque (Gazi Husrev-beg) whose restoration was funded and supervised by Saudis, was stripped of its ornate Ottoman tilework and painted wall decorations, to the disapproval of some local Muslims.[92])

Televangelism

One of the most popular Islamic preachers is Indian "televangelist",[93][94] Zakir Naik, a controversial figure who believes that then US President George W. Bush orchestrated the 9/11 attacks.[95][96] Naik dresses in a suit rather than traditional garb and gives colloquial lectures [97] speaking in English not Urdu.[98] His Peace TV channel, reaches a reported 100 million viewers,[95][98] According to Indian journalist Shoaib Daniyal, Naik's "massive popularity amongst India’s English-speaking Muslims" is a reflection of "how deep Salafism has spread its roots".[98]

Naik has gotten at least some publicity and funds in the form of Islamic awards from Saudi and other Gulf states:

- He won the $200,000 2015 King Faisal International Prize for Services to Islam;[99]

- Islamic Personality of the Year Award 2013 from The Dubai International Holy Quran Award.[100][101] The award was presented by Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Ruler of Dubai and Minister of Finance and Industry of the United Arab Emirates;[102]

- The 2013 Sharjah Award for Voluntary Work from the Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, Ruler of Sharjah[103]

Other means

According to critic Khaled Abou El Fadl, the funding available to those who support Wahhabi views has incentivized Muslim "schools, book publishers, magazines, newspapers, or even governments" around the world to "shape their behavior, speech, and thought in such a way as to incur and benefit from Saudi largesse." An example being the salary for "a Muslim scholar spending a six-month sabbatical" at a Saudi Arabian university, is more than ten years of pay "teaching at the Azhar University in Egypt." Thus acts such as "failing to veil" or failing to "advocate the veil" can mean the difference between "enjoying a decent standard of living or living in abject poverty.” [104]

Another incentive available to the Saudi Arabia, according to Abou el Fadl, is the power to grant or deny scholars a visa for hajj.[105]

Books by critics of Wahahbism and by competing Muslim thinkers have been made scarce by Saudis who have "successfully preventing the republication" or otherwise "buried" copies of their work, according to Abou el Fadl. Examples of such authors are early Salafi Rashid Rida, Yemeni jurist Muhammad al-Amir al-Husayni al-San'ani, and Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's own brother and critic Sulayman Ibn Abd al-Wahhab. [106] [107]

One critic who suffered at the hands of Wahhabism was an influential Salafi jurist, Muhammad al-Ghazali (d. 1996) who wrote a "critique of the influence of Wahhabism upon the "Salafi creed"—its "literalism, anti-rationalism, and anti-interpretive approach to Islamic texts". Despite the fact that al-Ghazali took care to use the term "Ahl al-Hadith" not "Wahhabi", the reaction to his book was "frantic and explosive", according to Abou el Fadl. Not only did a "large number" of "puritans" write to condemn al-Ghazali and "to question his motives and competence", but "several major" religious conferences were held in Egypt and Saudi Arabia to criticize the book, and the Saudi newspaper al-Sharq al-Awsat published "several long article responding to al-Ghazali."[108] Saudi Wahhabis "successfully preventing the republication of his work" even in his home country of Egypt, and "generally speaking made his books very difficult to locate."[108]

Islamic banking

One mechanism for the redistribution of (some) oil revenues from Saudi Arabia and other Muslim oil-exporters, to the poorer Muslim nations of African and Asia, was the Islamic Development Bank. Headquartered in Saudi Arabia, it opened for business in 1975. Its lenders and borrowers were member states of Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) and it strengthened "Islamic cohesion" between them. [109]

Saudi Arabians also helped establish Islamic banks with private investors and depositors. DMI (Dar al-Mal al-Islami: the House of Islamic Finance), founded in 1981 by Prince Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud,[110] and the Al Baraka group, established in 1982 by Sheik Saleh Abdullah Kamel (a Saudi billionaire), were both transnational holding companies.[111]

By 1995, there were "144 Islamic financial institutions worldwide", (not all of them Saudi financed) including 33 government-run banks, 40 private banks, and 71 investment companies.[111] As of 2014, about $2 trillion of banking assets were "sharia-compliant".[112]

Migration

By 1975, over one million workers—from unskilled country people to experienced professors, from Sudan, Pakistan, India, Southeast Asia, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria—had moved the Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states to work, and return after a few years with savings. A majority of these workers were Arab and most were Muslim. Ten years later the number had increased to 5.15 million and Arabs were no longer in the majority. 43% (mostly Muslims) came from the Indian subcontinent. In one country, Pakistan, in a single year, (1983),[113]

"the money sent home by Gulf emigrants amounted to $3 billion, compared with a total of $735 million given to the nation in foreign aid. .... The underpaid petty functionary of yore could now drive back to his hometown at the wheel of a foreign car, build himself a house in a residential suburb, and settle down to invest his savings or engage in trade.... he owed nothing to his home state, where he could never have earned enough to afford such luxuries." [113]

Muslims who had moved to Saudi Arabia, or other "oil-rich monarchies of the peninsula" to work, often returned to their poor home country following religious practice more intensely, particularly practices of Wahhabi Muslims. Having "grown rich in this Wahhabi milieu" it was not surprising that the returning Muslims believed there was a connection between that milieu and "their material prosperity", and that on return they followed religious practices more intensely and that those practices followed Wahhabi tenants.[114] Kepel gives examples of migrant workers returning home with new affluence, asking to be addressed by servants as "hajja" rather than "Madame" (the old bourgeois custom).[91] Another imitation of Saudi Arabia adopted by affluent migrant workers was increased segregation of the sexes, including shopping areas.[115][116] (It has also been suggested that Saudi Arabia has used cutbacks on the number of workers from a country allowed to work in it to punish a country for domestic policies it disapproves of.[117])

As of 2013 there are some 9 million registered foreign workers and at least a few million more illegal immigrants in Saudi Arabia, about half of the estimated 16 million citizens in the kingdom.[118]

State leadership

In the 1950s and 1960s Gamal Abdel Nasser, the leading exponent of Arab nationalism and the president of the Arab world's largest country had great prestige and popularity among Arabs. [119] However, in 1967 Nasser led the Six-Day War against Israel which ended not in the elimination of Israel but in the decisive defeat of the Arab forces[120] and loss of a substantial chunk of Egyptian territory. This defeat, combined with the economic stagnation from which Egypt suffered, were contrasted six years later with an embargo by the Arab "oil-exporting countries" against Israel's western allies that stopped Israel's counter offensive, and Saudi Arabia great economic power.[28][121]

This not only devastated Arab nationalism vis-a-vis the Islamic revival for the hearts and minds of Arab Muslims but changed "the balance of power among Muslim states", with Saudi Arabia and other oil-exporting countries gaining as Egypt lost influence. The oil-exporters emphasized "religious commonality" among Arabs, Turks, Africans, and Asians, and downplayed "differences of language, ethnicity, and nationality." [67] The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation—whose permanent Secretariat is located in Jeddah in Western Saudi Arabia—was founded after the 1967 war.

Saudi Arabia has expressed its displeasure with policies of poor Muslim countries by not hired or expelled nationals from the country, thus denying it badly needed workers' remittances. In 2013 it punished the government of Bangladesh by lessened the number of Bangladeshis allowed to enter Saudi after a crackdown in Bangladesh on the Islamist Jamaat-e Islami party, which according to the Economist magazine "serves as a standard-bearer" for Saudi Arabia's "strand of Islam in Bangladesh". (In fiscal year 2012, Bangladesh received $3.7 billion in official remittances from Saudi Arabia, "which is quite a lot more than either receives in economic aid.")[51]

Military jihad

| Part of a series on |

| Jihadism |

|---|

|

| Islamic fundamentalism |

| Notable jihadist organisations |

| Jihadism in the East |

| Jihadism in the West |

|

|

During the 1980s and ’90s, the monarchy and the clerics of Saudi Arabia helped to channel tens of millions of dollars to Sunni jihad fighters in Afghanistan, Bosnia and elsewhere.[122] While apart from the Afghan jihad against the Soviets and perhaps the Taliban jihad, the jihads may not have worked to propagate conservative Islam, and the numbers of their participants was relatively small, they did have considerable impact.

Afghan jihad against Soviets

The Afghan jihad against the Soviet Army following the Soviet's December 1979 invasion of Kabul Afghanistan, has been called a "great cause with which Islamists worldwide identified,"[123] and the “peak of Wahhabi-revivalist collaboration and triumph.”[124] The Saudi spent several billion dollars (along with the United States and Pakistan), supported with "financing, weaponry, and intelligence" the native Afghan and "Afghan Arabs" mujahidin (fighters of jihad) fighting the Soviets and their Afghan allies.[125] The Saudi government provided approximately $4 billion in aid to the mujahidin from 1980-1990, that went primarily to militarily ineffective but ideologically kindred Hezbi Islami and Ittehad-e Islami.[126] Other funding for volunteers came from the Saudi Red Crescent, Muslim World League, and privately, from Saudi princes.[127] At "training camps and religious schools (madrasa)" across the frontier in Pakistan—more than 100,000 Muslim volunteer fighters from 43 countries over the years—were provided with "radical, extremist indoctrination".[125][128] Mujahidin training camps in Pakistan trained not just volunteers fighting the Soviets but Islamists returning to Kashmir (including the Kashmir Hizb-i Islami) and Philippine (Moros), among others.[66] Among the foreign volunteers there were more Saudi nationals than any other nationality in 2001 according to Jane's International Security.[129] In addition to training and indoctrination the war served as “as a crucible for the synthesis of desperate Islamic revivalist organizations into loose coalition of likeminded jihadist groups that viewed the war" not as a struggle between freedom and foreign tyranny, but "between Islam and unbelief.”[130] The war turned Jihadists from a "relatively insignificant" group into "a major force in the Muslim world."[131]

The 1988-89 Soviet's withdrawal from Afghanistan leaving the Soviet allied Afghan Marxists to their own fate was interpreted jihad fighters and supporters as "a sign of God’s favor and the righteousness of their struggle.”[132] Afghan Arabs volunteers returned from Afghanistan to join local Islamist groups in struggles against their allegedly “apostate” governments. Others went to fight jihad in places such as Bosnia, Chechnya and Kashmir.[133] In at least one case a former Soviet fighter -- Jumma Kasimov of Uzbekistan—went on to fight jihad in his ex-Soviet Union state home, setting up the headquarters of his Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan in Taliban Afghanistan in 1997,[134] and reportedly given millions of dollars worth of aid by Osama bin Laden.[135]

Saudi Arabia saw its support for jihad against the Soviets as a way to counter the Iranian revolution—which initially generated considerable enthusiasm among Muslims—and contain its revolutionary, anti-monarchist influence (and also Shia influence in general) in the region.[38] Its funding was also accompanied by Wahhabi literature and preachers who helped propagate the faith. With the help of Pakistani Deobandi groups, it oversaw the creation of new madrassas and mosques in Pakistan, which increased the influence of Sunni Wahhabi Islam in that country and prepare recruits for the jihad in Afghanistan.[136]

Afghanistan Taliban

During the Soviet-Afghan war, Islamic schools (madrassas) for Afghan refugees in Pakistan appeared in the 1980s near the Afghan-Pakistan border. Initially funded by zakat donations from Pakistan, nongovernmental organizations in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states became "important backers" later on.[137] Many were radical schools sponsored by the Pakistan JUI religious party and became "a supply line for jihad" in Afghanistan.[137] According to analysts the ideology of the schools became "hybridization" of the Deobandi school of the Pakistani sponsors and the Salafism supported by Saudi financers.[138][139]

Several years after the Soviet withdrawal and fall of the Marxist government, many of these Afghan refugee students developed as a religious-political-military force[140] to stop the civil war among Afghan mujahideen factions and unify (most of) the country under their "Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan". (Eight Taliban government ministers came from one school, Dar-ul-Uloom Haqqania.[141]) While in power, the Taliban implemented the "strictest interpretation of Sharia law ever seen in the Muslim world,"[142] and was noted for its harsh treatment of women.[143]

Saudis helped the Taliban in a number of ways. Saudi Arabia was one of only three countries (Pakistan and United Arab Emirates being the others) officially to recognize the Taliban as the official government of Afghanistan before the 9/11 attacks, (after 9/11 no country recognized it). King Fahd of Saudi Arabia “expressed happiness at the good measures taken by the Taliban and over the imposition of shari’a in our country," During a visit by the Taliban’s leadership to the kingdom in 1997.[144]

According to Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid who spent much time in Afghanistan, in the mid 1990s the Taliban asked Saudis for money and materials. Taliban leader Mullah Omar told Ahmed Badeeb, the chief of staff of the Saudi General Intelligence: `Whatever Saudi Arabia wants me to do, ... I will do`. The Saudis in turn "provided fuel, money, and hundreds of new pickups to the Taliban ... Much of this aid was flown in to Kandahar from the Gulf port city of Dubai," according to Rashid. Another source, a witness to lawyers for the families of 9/11 victims, testified in a sworn statement that in 1998 he had seen an emissary for the director general of Al Mukhabarat Al A'amah, Saudi Arabia's intelligence agency prince, Turki bin Faisal Al Saud, hand a check for one billion Saudi riyals (approximately $267 million as of 10/2015) to a top Taliban leader in Afghanistan.[145] (The Saudi government denies providing any funding and it is thought that the funding came not from the government but from wealthy Saudis and possibly other gulf Arabs who were urged to support the Taliban by the influential Saudi Grand Mufti Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz. [146]) After the Taliban captured the Afghan capital Kabul, Saudi expat Osama bin Laden—who though in very bad graces with the Saudi government was very much an influenced by Wahhabism or the Muslim Brotherhood-Wahhabi hybrid—provided the Taliban with funds, use of his training camps and veteran "Arab-Afghan forces for combat, and engaged in all-night conversations with the Taliban leadership.[127]

Saudi Wahhabism practices, influenced the Taliban. One example was the Saudi religious police, according to Rashid.

`I remember that all the Taliban who had worked or done hajj in Saudi Arabia were terribly impressed by the religious police and tried to copy that system to the letter. The money for their training and salaries came partly from Saudi Arabia.`

The taliban also practiced public beheadings common in Saudi Arabia. Ahmed Rashid came across ten thousand men and children gathering at Kandahar football stadium one Thursday afternoon, curious as to why (the Taliban had banned sports) he "went inside to discover a convicted murderer being led between the goalposts to be executed by a member of the victim's family." [147]

The Taliban's brutal treatment of Shia, and the destruction of Buddhist statues in Bamiyan Valley may also have been influenced by Wahhabism, which had a history of attacking and takfiring Shia, while prior to this attack Afghan Muslims had never persecuted their Shia minority.[148] In late July 1998, the Taliban used the trucks (donated by Saudis) mounted with machine guns to capture the northern town of Mazar-e-Sharif. "Ahmed Rashid later estimated that 6000 to 8000 Shia men, women and children were slaughtered in a rampage of murder and rape that included slitting people's throats and bleeding them to death, halal-style, and baking hundreds of victims into shipping containers without water to be baked alive in the desert sun." [149] This reminded at least one writer (Dore Gold) of the Wahhabi attack on Shia shrine in Karbala in 1802.[148]

Another activity Afghan Muslims had not engaged in before this time was destruction of statues. In 2001, the Taliban dynamited and rocketed the nearly 2000-year-old statues Buddhist Bamiyan Valley, which had been undamaged by Afghan Sunni Muslim for centuries prior to then. Mullah Omar declared "Muslims should be proud of smashing idols. It has given praise to Allah that we have destroyed them."[150]

Other jihads

From 1981 to 2006 an estimated 700 terror attacks outside of combat zones were perpetrated by Sunni extremists (usually Jihadi Salafis such as Al-Qaeda), killing roughly 7,000 people.[151] What connection, if any, there is between Wahhabism and Saudi Arabia on the one hand and Jihadi Salafis on the other, is disputed. Allegations of Saudi links to terrorism "have been the subject of years" of US "government investigations and furious debate".[145] Wahhabism has been called "the fountainhead of Islamic extremism that promotes and legitimizes" violence against civilians (Yousaf Butt)[152]

Between the mid-1970s and 2002 Saudi Arabia provided over $70 billion in "overseas development aid",[153] the vast majority of this development being religious, specifically the propagation and extension of the influence of Wahhabism at the expense of other forms of Islam.[154] There has been an intense debate over whether Saudi aid and Wahhabism has fomented extremism in recipient countries.[155] The two main ways in which Wahhabism and its funding is alleged to be connected to terror attacks are through

- Basic teachings. Wahhabi interpretations of Islam encourages intolerance, in fact hatred towards non-Muslims. Insofar as those hated and found intolerable are subject to violence, Wahhabi teachings leads to violence. The interpretation is spread (among other ways) by textbooks in Saudi Arabia and in "thousands of schools worldwide funded by fundamentalist Sunni Muslim charities".[156][157][158]

- Funding attacks. The Saudi government and Saudi charitable foundations run by religious Wahhabis have directly aided terrorists and terrorist groups financially.[159] According to at least one source (Anthony H. Cordesman) this flow of money from the Kingdom to outside extremist has "probably" had more effect that the kingdom's "religious thinking and missionary efforts".[160] In addition to donations by sincere believers in jihadism working in the charities, money for terrorists also comes as a form of pay off to terrorist groups by some members of the Saudi ruling class in part to keep the jihadists from being more active in Saudi Arabia, according to critics.[145] During the 1990s Al Qaeda and Jihad Islamiyya (JI) filled leadership positions in several Islamic charities with some of their most trusted men (Abuza, 2003). Al Qaeda and JI’s operatives were then diverting about 15-20% and in some cases as much as 60% of the funds to finance their operations.[161] Zachary Abuza estimates that the 300 private Islamic charities have established their base of operations in Saudi Arabia have distributed over $10 billion worldwide in support of an “Wahhabi-Islamist agenda”.[162] Contributions from well off and wealthy Saudi's come from zakat, but contributions are often more like 10% rather than the obligatory 2.5% of their income producing assets, and are followed up with minimal if any investigation of the contributions results.[160]

- Funding before 2003

American politicians and media have accused the Saudi government of supporting terrorism and tolerating a jihadist culture,[163] noting that Osama bin Laden and fifteen out of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia.[164]

In 2002 a Council on Foreign Relations Terrorist Financing Task Force report found that: “For years, individuals and charities based in Saudi Arabia have been the most important source of funds for al-Qaeda. And for years, Saudi officials have turned a blind eye to this problem.”[165]

According to a July 10, 2002 briefing given to the US Department of Defense Defense Policy Board, ("a group of prominent intellectuals and former senior officials that advises the Pentagon on defense policy.") by a Neo-Conservative (Laurent Murawiec, a RAND Corporation analyst), "The Saudis are active at every level of the terror chain, from planners to financiers, from cadre to foot-soldier, from ideologist to cheerleader," [166]

Some examples of funding are checks written by Princess Haifa bint Faisal—the wife of Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi ambassador to Washington—totaling as much as $73,000 ended up with Omar al-Bayoumi, a Saudi who hosted and otherwise helped two of the September 11 hijackers when they reached America. They [167][168]

Imprisoned former al-Qaeda operative, Zacarias Moussaoui, stated in deposition transcripts filed in February 2015 that more than a dozen prominent Saudi figures, (including Prince Turki al-Faisal Al Saud, a former Saudi intelligence chief) donated to al Qaeda in the late 1990s. Saudi officials have denied this.[169]

Lawyers filing a lawsuit against Saudi Arabia for the families of 9/11 victims provided documents including

- an interview with a "self-described Qaeda operative in Bosnia" who said that the Saudi High Commission for Relief of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a charity "largely controlled by members of the royal family", provided "money and supplies to al-Qaeda" in the 1990s and "hired militant operatives" like himself.[145]

- a "confidential German intelligence report" with "line-by-line" descriptions of bank transfers with "dates and dollar amounts" made in the early 1990s, indicating tens of millions of dollars where sent by Prince Salman bin Abdul Aziz (now King of Saudi Arabia) and other members of the Saudi royal family to a "charity that was suspected of financing militants’ activities in Pakistan and Bosnia".[145]

- Post-2003

In 2003 there were several attacks by Al-Qaeda-connected terrorists on Saudi soil and according to American officials, in the decade since then the Saudi government has become a "valuable partner against terrorism", assisting in the fight against al-Qaeda and the Islamic State.[122]

However, there is some evidence Saudi support for terror continues.

According to internal documents from the U.S. Treasury Department, the International Islamic Relief Organization (released by the aforementioned 9/11 family lawyers) -- a prominent Saudi charity heavily supported by members of the Saudi royal family—showed “support for terrorist organizations” at least through 2006.[145]

US diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks in 2010 contain numerous complaints of funding of Sunni extremists by Saudis and other Gulf Arabs. According to a 2009 U.S. State Department communication by then United States Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, "donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide"[170]—terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda, the Afghan Taliban, and Lashkar-e-Taiba in South Asia, for which "Saudi Arabia remains a critical financial support base".[171][172] Part of this funding arises through the zakat charitable donations (one of the "Five Pillars of Islam") paid by all Saudis to charities, and amounting to at least 2.5% of their income. It is alleged that some of the charities serve as fronts for money laundering and terrorist financing operations, and further that some Saudis "know full well the terrorist purposes to which their money will be applied".[173]

According to the US cable the problem is acute in Saudi Arabia, where militants seeking donations often come during the hajj season purporting to be pilgrims. This is "a major security loophole since pilgrims often travel with large amounts of cash and the Saudis cannot refuse them entry into Saudi Arabia". They also set up front companies to launder funds and receive money "from government-sanctioned charities".[172] Clinton complained in the cable of the "challenge" of persuading "Saudi officials to treat terrorist funds emanating from Saudi Arabia as a strategic priority", and that the Saudis had refused to ban three charities classified by the US as terrorist entities, despite the fact that, "Intelligence suggests" that the groups "at times, fund extremism overseas".[172]

Besides Saudi Arabia, businesses based in the United Arab Emirates provide "significant funds" for the Afghan Taliban and their militant partners the Haqqani network according to one US embassy cable released by Wikileaks.[174] According to a January 2010 US intelligence report, "two senior Taliban fundraisers" had regularly travelled to the UAE, where the Taliban and Haqqani networks laundered money through local front companies.[172] (The reports complained of weak financial regulation and porous borders in the UAE, but not difficulties in persuading UAE officials of terrorist danger.) Kuwait was described as a "source of funds and a key transit point" for al-Qaida and other militant groups, whose government was concerned about terror attacks on its own soil, but "less inclined to take action against Kuwait-based financiers and facilitators plotting attacks" in our countries.[172] Kuwait refused to ban the Society of the Revival of Islamic Heritage, which the US had designated a terrorist entity in June 2008 for providing aid to al-Qaida and affiliated groups, including LeT.[172] According to the cables, "overall level" of counter-terror co-operation with the U.S. was "considered the worst in the region".[172] More recently, in late 2014, US Vice President also complained "the Saudis, the Emirates" had "poured hundreds of millions of dollars and tens of tons of weapons" into Syria for "al-Nusra, and al-Qaeda, and the extremist elements of jihadis."[152]

In October 2014 Zacarias Moussaoui, an Al-Qaeda member imprisoned in the US testified under oath that members of the Saudi royal family supported al Qaeda. According to Moussaoui, he was tasked by Osama bin Laden with creating a digital database to catalog al Qaeda's donors, and that donors he entered into the database including several members of the Saudi Royal family, including Prince Turki al-Faisal Al Saud, former director-general of Saudi Arabia's Foreign Intelligence Service and ambassador to the United States, and others he named in his testimony. Saudi government representatives have denied the charges. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, while it is possible that charities with significant Saudi government sponsorship diverted funds to al Qaeda, and "Saudi Arabia has long been considered the primary source of al Qaeda funding, ... we have found no evidence that the Saudi government as an institution or senior Saudi officials individually funded the organization."[175]

- Teachings

Among those who believe there is, or may be, a connection between Wahhabist ideology and Al-Qaeda include F. Gregory Gause III[176][177] Roland Jacquard,[178] Rohan Gunaratna,[179] Stephen Schwartz.[180] Dore Gold points out that bin Laden was not only given a Wahhabi education but among other pejoratives accused his target—the United States—of being "the Hubal of the age",[181] in need of destruction. Focus on Hubal, the seventh century stone idol, follows the Wahhabi focus on the importance of the need to destroy any and all idols.[182]

Biographers of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed ("architect" of the 9/11 attacks) and Ramzi Yousef (leader of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing that Yousef hoped would topple the North Tower, killing tens of thousands of office workers) have noted the influence of Wahhabism through Ramzi Yousef's father, Muhammad Abdul Karim, who was introduced to Wahhabism in the early 1980s while working in Kuwait.[183][184]

Others connect the group to Sayyid Qutb and Political Islam. Academic Natana J. DeLong-Bas,[185] argues that though bin Laden "came to define Wahhabi Islam during the later years" of his life, his militant Islam "was not representative of Wahhabi Islam as it is practiced in contemporary Saudi Arabia"[186] Karen Armstrong states that Osama bin Laden, like most extremists, followed the ideology of Sayyid Qutb, not "Wahhabism".[187]

Noah Feldman distinguishes between what he calls the "deeply conservative" Wahhabis and what he calls the "followers of political Islam in the 1980s and 1990s," such as Egyptian Islamic Jihad and later Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. While Saudi Wahhabis were "the largest funders of local Muslim Brotherhood chapters and other hard-line Islamists" during this time, they opposed jihadi resistance to Muslim governments and assassination of Muslim leaders because of their belief that "the decision to wage jihad lay with the ruler, not the individual believer".[188][189]

More recently the self-declared "Islamic State" in Iraq and Syria headed by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has been described as both more violent than al-Qaeda and more closely aligned with Wahhabism.

For their guiding principles, the leaders of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, are open and clear about their almost exclusive commitment to the Wahhabi movement of Sunni Islam. The group circulates images of Wahhabi religious textbooks from Saudi Arabia in the schools it controls. Videos from the group's territory have shown Wahhabi texts plastered on the sides of an official missionary van.[190]

According to scholar Bernard Haykel, "for Al Qaeda, violence is a means to an ends; for ISIS, it is an end in itself." Wahhabism is the Islamic States "closest religious cognate."[190]

According to former British intelligence officer Alastair Crooke, ISIS "is deeply Wahhabist", but also "a corrective movement to contemporary Wahhabism."[191] In Saudi Arabia itself, the

ruling elite is divided. Some applaud that ISIS is fighting Iranian Shiite "fire" with Sunni "fire"; that a new Sunni state is taking shape at the very heart of what they regard as a historical Sunni patrimony; and they are drawn by Da'ish's strict Salafist ideology.[191]

Former CIA director James Woolsey described Saudi as "the soil in which Al-Qaeda and its sister terrorist organizations are flourishing."[173] However, the Saudi government strenuously denies these claims or that it exports religious or cultural extremism.[192]

- Individual Saudi nationals

Saudi intelligence sources estimate that from 1979 to 2001 as many as 25,000 Saudis received military training in Afghanistan and other locations abroad,[193] and many helped in jihad outside of the Kingdom.

According to Ali Al-Ahmed, "more than 6,000 Saudi nationals" have been recruited into al Qaeda armies in Iraq, Pakistan, Syria and Yemen "since the Sept. 11 attacks". In Iraq, an estimated 3,000 Saudi nationals, "the majority of foreign fighters", were fighting alongside Al Qaeda in Iraq.[194]

See also

Notes

- ↑ During the Afghan jihad against the Soviets, for example, in addition to the Saudi government, "Saudi movements or personalities such as Sheikh Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz, the highest authority of Wahhabism" had their own networks.[66]

References

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. pp. 61–2.

- 1 2 3 4 Roy, Olivier. The Failure of Political Islam. Harvard University Press. p. 117. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

The Muslim Brothers agreed not to operate in Saudi Arabia itself, but served as a relay for contacts with foreign Islamist movements. The MBs also used as a relay in South Asia movements long established on an indigenous basis (Jamaat-i Islami). Thus the MB played an essential role in the choice of organisations and individuals likely to receive Saudi subsidies. On a doctrinal level, the differences are certainly significant between the MBs and the Wahhabis, but their common references to Hanbalism ... their rejection of the division into juridical schools, and their virulent opposition to Shiism and popular religious practices (the cult of 'saints') furnished them with the common themes of a reformist and puritanical preaching. This alliance carried in its wake older fundamentalist movements, non-Wahhabi but with strong local roots, such as the Pakistani Ahl-i Hadith or the Ikhwan of continental China

- 1 2 Gold, Dore (2003). Hatred's Kingdom : How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism. Regnery. p. 237.

- 1 2 3 Kepel, Gilles (2004). The War for Muslim Minds: Islam and the West. Harvard University Press. p. 156. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

In the melting pot of Arabia during the 1960s, local clerics trained in the Wahhabite tradition joined with activists and militants affiliated with the Muslims Brothers who had been exiled from the neighboring countries of Egypt, Syria and Iraq .... The phenomenon of Osama bin Laden and his associates cannot be understood outside this hybrid tradition.

- 1 2 3 Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 51.

Well before the full emergence of Islamism in the 1970s, a growing constituency nicknamed `petro-Islam` included Wahhabi ulemas and Islamist intellectuals and promoted strict implementation of the sharia in the political, moral and cultural spheres; this proto-movement had few social concerns and even fewer revolutionary ones.

- ↑ JASSER, ZUHDI. "STATEMENT OF ZUHDI JASSER, M.D., PRESIDENT, AMERICAN ISLAMIC FORUM FOR DEMOCRACY. 2013 ANTI–SEMITISM: A GROWING THREAT TO ALL FAITHS. HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES" (PDF). FEBRUARY 27, 2013. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. p. 27. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

Lastly, the Saudis spent tens of billions of dollars throughout the world to pump Wahhabism or petro-Islam, a particularly virulent and militant version of supremacist Islamism.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Youssef Michel (August 11, 2002). "The Mideast Threat That's Hard to Define". cfr.org. The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

... money that brought Wahabis power throughout the Arab world and financed networks of fundamentalist schools from Sudan to northern Pakistan.

- ↑ According to author Dore Gold this funding was for non-Muslim countries alone. Gold, Dore (2003). Hatred's Kingdom : How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism. Regnery. p. 126.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Youssef Michel (August 11, 2002). "The Mideast Threat That's Hard to Define". Council on foreign relations. Washington Post. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑ House, Karen Elliott (2012). On Saudi Arabia : Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines and Future. Knopf. p. 234.

A former US Treasury Department official is quoted by Washington Post reporter David Ottaway in a 2004 article [Ottaway, David The King's Messenger New York: Walker, 2008, p.185] as estimating that the late king [Fadh] spent `north of $75 billion` in his efforts to spread Wahhabi Islam. According to Ottaway, the king boasted on his personal Web site that he established 200 Islamic colleges, 210 Islamic centers, 1500 mosques, and 2000 schools for Muslim children in non-Islamic nations. The late king also launched a publishing center in Medina that by 2000 had distributed 138 million copies of the Koran worldwide.

- ↑ Lacey, Robert (2009). Inside the Kingdom : Kings, Clerics, Modernists, Terrorists, and the Struggle for Saudi Arabia. Viking. p. 95.

The Kingdom's 70 or so embassies around the world already featured cultural, educational, and military attaches, along with consular officers who organized visas for the hajj. Now they were joined by religious attaches, whose job was to get new mosques built in their countries and to persuade existing mosques to propagate the dawah wahhabiya.

- ↑ led by Prince Salman bin Abdul Aziz, now minister of defense, who often is touted as a potential future king

- ↑ House, Karen Elliott (2012). On Saudi Arabia : Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines and Future. Knopf. p. 234.

To this day, the regime funds numerous international organizations to spread fundamentalist Islam, including the Muslim World League, the World Assembly of Muslim Youth, the International Islamic Relief Organization, and various royal charities such as the Popular Committee for Assisting the Palestinian Muhahedeen, led by Prince Salman bin Abdul Aziz, now minister of defense, who often is touted as a potential future king. Supporting da'wah, which literally means `making an invitation` to Islam, is a religious requirement that Saudi rulers feel they cannot abandon without losing their domestic legitimacy as protectors and propagators of Islam. Yet in the wake of 9/11, American anger at the kingdom led the U.S. government to demand controls on Saudi largesse to Islamic groups that funded terrorism.

- 1 2 3 4 Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. I.B.Tauris. p. 141.

[MB founder Hasan al-Banna] shared with the Wahhabis a strong revulsion against western influences and unwavering confidence that Islam is both the true religion and a sufficient foundation for conducting worldly affairs ... More generally, Banna's [had a] keen desire for Muslim unity to ward off western imperialism led him to espouse an inclusive definition of the community of believers. ... he would urge his followers, `Let us cooperate in those things on which we can agree and be lenient in those on which we cannot.` ... A salient element in Banna's notion of Islam as a total way of life came from the idea that the Muslim world was backward and the corollary that the state is responsible for guaranteeing decent living conditions for its citizens.

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: On the Trail of Political Islam. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 220. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

Hostile as they were to the `sheikists`, the jihadist-salafists were even angrier with the Muslim Brothers, whose excessive moderation they denounced ...

- ↑ Armstrong, Karen (27 November 2014). "Wahhabism to ISIS: how Saudi Arabia exported the main source of global terrorism". New Statesman. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

A whole generation of Muslims, therefore, has grown up with a maverick form of Islam [i.e. Wahhabism] that has given them a negative view of other faiths and an intolerantly sectarian understanding of their own. While not extremist per se, this is an outlook in which radicalism can develop.

- ↑ Pabst, Adrian. "Pakistan must confront Wahhabism". Guardian.

Unlike many Sunnis in Iraq, most Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan have embraced the puritanical and fundamentalist Islam of the Wahhabi mullahs from Saudi Arabia who wage a ruthless war not just against western "infidels" but also against fellow Muslims they consider to be apostates, in particular the Sufis. ... in the 1980s ... during the Afghan resistance against the Soviet invasion, elements in Saudi Arabia poured in money, arms and extremist ideology. Through a network of madrasas, Saudi-sponsored Wahhabi Islam indoctrinated young Muslims with fundamentalist Puritanism, denouncing Sufi music and poetry as decadent and immoral.

- ↑ Algar, Hamid (2002). Wahhabism: A Critical Essay. Oneonta, NY: Islamic Publications International. p. 48.

What has aptly been called the Arab Cold War was then [in the 1960s] underway: a struggle between the camps led respectively by Egypt and its associates and Saudi Arabia and its friends." [a proxy war with Egypt in Yemen was being waged, and on the political front Saudi Arabia was proclaiming] "`Islamic solidarity` with such implausible champions of Islam as Bourguiba and Shah [both secularists] "And on the ideological front, it established in 1962 -- not coincidentally, the same year as the republican uprising in neighboring Yemen -- a body called the Muslim World League (Rabitat al-`Alam al-Islami)

- ↑ It may also have changed Saudi desire to propagate Wahhabism. Abou El Fadl, Khaled (2005). The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists. Harper San Francisco. p. 70.

Before the 1970s, the Saudis acted as if Wahhabism was an internal affair well adapted to native needs of Saudi society and culture. The 1970s became a turning point in that the Saudi government decided to undertake a systematic campaign of aggressively exporting the Wahhabi creed to the rest of the Muslim world.

- ↑

- 1 2 Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 70.

Prior to 1973, Islam was everywhere dominated by national or local traditions rooted in the piety of the common people, with clerics from the different schools of Sunni religious law established in all major regions of the Muslim world (Hanafite in the Turkish zones of South Asia, Malakite in Africa, Shafeite in Southeast Asia), along with their Shiite counterparts. This motley establishment held Saudi inspired puritanism in great suspicion on account of its sectarian character. But after 1973, the oil-rich Wahhabites found themselves in a different economic position, being able to mount a wide-ranging campaign of proselytizing among the Sunnis. (The Shiites, whom the Sunnis considered heretics, remained outside the movement.) The objective was to bring Islam to the forefront of the international scene, to substitute it for the various discredited nationalist movements, and to refine the multitude of voices within the religion down to the single creed of the masters of Mecca. The Saudis' zeal now embraced the entire world ... [and in the West] immigrant Muslim populations were their special target."

- ↑ Abou El Fadl, Khaled (2002). The Place of Tolerance in Islam by Khaled Abou El Fadl The Place of Tolerance in Islam. Beacon Press. p. 6. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ (from The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists, by Khaled Abou El Fadl, Harper San Francisco, 2005 , p.160)

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia. Wahhabi Theology". December 1992. Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ↑ House, Karen Elliott (2012). On Saudi Arabia : Its People, past, Religion, Fault Lines and Future. Knopf. p. 27.

Not only is the Saudi monarch effectively the religious primate, but the puritanical Wahhabi sect of Islam that he represents instructs Muslims to be obedient and submissive to their ruler, however imperfect, in pursuit of a perfect life in paradise. Only if a ruler directly countermands the comandments of Allah should devout Muslims even consider disobeying. `O you who have believed, obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you. [surah 4:59]`

- ↑ Sharp, Arthur G. "What's a Wahhabi?". net places. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ Algar, Hamid (2002). Wahhabism: A Critical Essay. Oneonta, NY: Islamic Publications International. pp. 33–34.

Algar lists all these things that involve intercession in prayer, that Wahhabi believe violate the principle of tauhid al-`ibada (directing all worship to God alone). "all the allegedly deviant practices just listed can, however, be vindicated with reference not only to tradition and consensus but also hadith, as has been explained by those numerous scholars, Sunni and Shi'i alike, who have addressed the phenomenon of Wahhabism. Even if that were not the case, and the belief that ziyara or tawassul is valid and beneficial were to be false, there is no logical reason for condemning the belief as entailing exclusion from Islam.

- 1 2 3 Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 69.

"The war of October 1973 was started by Egypt with the aim of avenging the humiliation of 1967 and restoring the lost legitimacy of the two states' ... [Egypt and Syria] emerged with a symbolic victory ... [but] the real victors in this war were the oil-exporting countries, above all Saudi Arabia. In addition to the embargo's political success, it had reduced the world supply of oil and sent the price per barrel soaring. In the aftermath of the war, the oil states abruptly found themselves with revenues gigantic enough to assure them a clear position of dominance within the Muslim world.

- ↑ "The price of oil – in context". CBC News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2006). "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism". Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. pp. 61–2.

"the financial clout of Saudi Arabia ... had been amply demonstrated during the oil embargo against the United States, following the Arab-Israeli war of 1973. This show of international power, along with the nation's astronomical increase in wealth, allowed Saudi Arabia's puritanical, conservative Wahhabite faction to attain a preeminent position of strength in the global expression of Islam. Saudi Arabia's impact on Muslims throughout the world was less visible than that of Khomeini's Iran, but the effect was deeper and more enduring. The kingdom seized the initiative from progressive nationalism, which had dominated the [Arab world in the] 1960s, it reorganized the religious landscape by promoting those associations and ulemas who followed its lead, and then, by injecting substantial amounts of money into Islamic interests of all sorts, it won over many more converts. Above all, the Saudis raised a new standard -- the virtuous Islamic civilization -- as a foil for the corrupting influence of the West ...

- ↑ source: Ian Skeet, OPEC: Twenty-Five Years of Prices and Politics (Cambridge: University Press, 1988)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.75

- ↑ Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed : Inside a Kingdom in Crisis. Palgrave. p. 112.

... in the wake of the oil boom Saudis had money, .... [and it] appeared to validate them in their Saudi-ness. They believed that they deserved their windfall, that the treasure the kingdom sits on is in some ways a gift from God, a reward for having spread the message of Islam from a land that had hitherto seemed barren in every respect. The sudden oil wealth entrenched a sense of self-righteousness and arrogance among many Saudis, appeared to vindicate them in their separateness from other cultures and religions. In the process, it reconfirmed the belief that the greater the Western presence, the greater the potential threat to everything they held dear.

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2006). "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism". Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 70.

The propagation of the faith was not the only issue for the leaders in Riyadh. Religious obedience on the part of the Saudi population became the key to winning government subsidies, the kingdom's justification for its financial pre-eminence, and the best way to allay envy among impoverished co-religionists in Africa and Asia. By becoming the managers of a huge empire of charity and good works, the Saudi government sought to legitimize a prosperity it claimed was manna from heaven, blessing the peninsula where the Prophet Mohammed had received his Revelation. Thus, an otherwise fragile Saudi monarchy buttressed its power by projecting its obedient and charitable dimension internationally.

- ↑ Ayubi, Nazih N. (1995). Over-stating the Arab State: Politics and Society in the Middle East. I.B.Tauris. p. 232.

The ideology of such regimes has been pejoratively labelled by some `petro-Islam.` This is mainly the ideology of Saudi Arabia but it is also echoed to one degree or another in most of the smaller Gulf countries. Petro-Islam proceeds from the premise that it is not merely an accident that oil is concentrated in the thinly populated Arabian countries rather than in the densely populated Nile Valley or the Fertile Crescent, and that this apparent irony of fate is indeed a grace and a blessing from God (ni'ma; baraka) that should be solemnly acknowledged and lived up to.

- ↑ Gilles Kepel and Nazih N. Ayubi both use the term Petro-Islam, but others subscribe to this view as well, example: Sayeed, Khalid B. (1995). Western Dominance and Political Islam: Challenge and Response. SUNY Press. p. 95.

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.69

- 1 2 Roy, Failure of Political Islam, 1994: p.116

- ↑ Gold, Hatred's Kingdom, 2003: p.126

- 1 2 Stanley, Trevor (July 15, 2005). "Understanding the Origins of Wahhabism and Salafism". Terrorism Monitor Volume. Jamestown Foundation. 3 (14). Retrieved 2 January 2015.

Although Saudi Arabia is commonly characterized as aggressively exporting Wahhabism, it has in fact imported pan-Islamic Salafism. Saudi Arabia founded and funded transnational organizations and headquartered them in the kingdom, but many of the guiding figures in these bodies were foreign Salafis. The most well known of these organizations was the World Muslim League, founded in Mecca in 1962, which distributed books and cassettes by al-Banna, Qutb and other foreign Salafi luminaries. Saudi Arabia successfully courted academics at al-Azhar University, and invited radical Salafis to teach at its own Universities.

- 1 2 3 Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.51

- ↑ Kepel, War for Muslim Minds, (2004) p.174-5

- ↑ Abouyoub, Younes (2012). "21. Sudan, Africa's Civilizational Fault Line ...". In Mahdavi, Mojtaba. Towards the Dignity of Difference?: Neither 'End of History' nor 'Clash of ... Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 382.

- ↑ Riedel, Bruce (September 11, 2011). "The 9/11 Attacks' Spiritual Father". Brooking. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ Azzam, Abdullah (c. 1993). "DEFENSE OF THE MUSLIM LANDS". archive.org. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

I wrote this Fatwa and its was originally larger than its present size. I showed it to our Great Respected Sheikh Abdul Aziz Bin Bazz. I read it to him, he improved upon it and he said "it is good" and agreed with it. But, he suggested to me to shorten it and to write an introduction for it with which it should be published. ... Likewise, I read it to Sheikh Mohammed Bin Salah Bin Uthaimin and he too signed it.

- ↑ David Sagiv, Fundamentalism and Intellectuals in Egypt, 1973-1999, (London: Frank Cass, 1995), p.47

- ↑ Nasr, Vali (2000). International Relations of an Islamist Movement: The Case of the Jama’at-i Islami of Pakistan (PDF). New York: council on foreign relations. p. 42. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Coll, Steve. Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from ... Penguin. p. 26.