Honoré Laval

.jpg)

Honoré Laval, SS.CC., (born Louis-Jacques Laval; 5/6 February 1808 – 1 November 1880) was a French Catholic priest of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (also known as the Picpus Fathers), a religious institute of the Roman Catholic Church, who evangelized the Gambier Islands.

Life

Louis-Jacques Laval was born 6 January 6, 1807, in the small hamlet of Joimpy, Saint-Léger-des-Aubées in Eure-et-Loir. He was professed in the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (Picpus) December 30, 1825, under the name of Brother Honore and was ordained priest in Rouen in 1831.[1]

The Gambier Islands

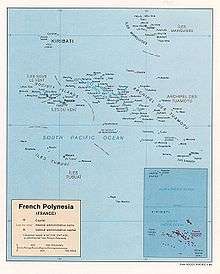

Accompanied by Fathers François Caret, Chrysostome Liausu, and Brother Columba Murphy, he travelled by coach from Paris via Tours and Poitiers to Bordeaux, where they boarded the Sylphide, which sailed on 1 February 1834 for Valparaíso, arriving on 13 May. Taking passage on Captain Sweetwood's ship, the Peruvian, out of Boston, Caret and Laval arrived 8 August on Akamaru in the Gambier Islands.[2]

From the 10th to the 15th centuries, the Gambiers hosted a population of several thousand people and traded with other island groups including the Marquesas, the Society Islands and Pitcairn Islands. However, excessive logging by the islanders resulted in almost complete deforestation on Mangareva, with disastrous results for the islands' environment and economy. The folklore of the islands records a slide into civil war and even cannibalism as trade links with the outside world broke down, and archaeological studies have confirmed this tragic story. When Laval and Caret arrived the population of the Gambiers was estimated at 800 to 1,000.[3] Karl Rensch says they counted 2,124 souls.[4]

The Gambiers were fairly isolated. Captain Arnaud Mauruc advised the Apostolic Prefect of Southern Oceania, Chrysostome Liausu, that ships only sailed there every five or seven years for pearl fishing as the area had no other commercial value.[3] Liausu remained in Valparaiso to maintain communications between the scattered missions and the Congregation in France. He died there in September 1839, having contracted typhus.

In August 1834 Caret and Laval arrived on Akamaru and found shelter with a French fisherman. King Maputeoa's uncle, Matua, helped them learn the Mangareva language. Maputeoa himself was converted and baptized in August 1836, perhaps under a suspicion that his uncle may have been planning to usurp the throne. Maputeoa took the name "Gregory" in honor of the Pope at that time.[2] The mission thrived. The maraes, (sacred places) were destroyed and shrines erected in the sites. The largely unclothed people were given clothing and cloth. On Caret's return from Europe in December 1838 2,157 items of clothing donated by the ladies of France were distributed.

The London Missionary Society, which had been based in Tahiti for thirty years, had established schools in the Gambiers, but subsequently withdrew from the Gambiers in early 1835. Bishop Étienne Jérôme Rouchouze, Laval's immediate superior, arrived in the Gambiers in May 1835, with two lay brothers, Brother Gilbert Soulié and Fabien Costes; a lay missionary, and two priests who were also medical doctors. During an epidemic that year Father Cyprien Liausu set up a hospital in a former temple at Rikitea.

Lay brothers Costes and Soulie train the local people in the building trades. They gain experience in the construction of chapels and houses. Together they build St. Michael's Cathedral, Rikitea. In 1856 Soulie and sixty workers travelled to Tahiti to work on Notre Dame Cathedral in Papeete. Ten years later, skilled Mangareva workers constructed the beacon at Point Venus in Tahiti.[5]

Caret and Laval hoped to expand their work to Tahiti, where they arrived in the Kingdom of Tahiti in February 1836. They found a place to stay in a house on the property of the American consul M. Moerenhout, a Belgian by birth, whom the British considered to be in the pay of King Louis Philippe I of France. Although the priests were received courteously at court, they were expelled by the Protestant queen Pōmare IV on advice of British missionary (and soon to be consul) George Pritchard.[6] Also expelled was a civilian French carpenter, named Vincent, who had accompanied the priests from Gambiers. These expulsions are the origin of the French intervention in Polynesia. As a result, in 1838 France sent Admiral Abel Aubert Dupetit Thouars to get reparation. Shortly before the Admiral's arrival, Madame Moerenhout was murdered during a robbery, which the French believed was instigated by the British.[7] Once his mission had been completed, Admiral DupetitThouars sailed towards the Marquesas Islands, which he annexed in 1842.

Caret and Laval then returned to the Gambiers. Caret returned to France in 1837 in search of additional resources; Bishop Rouchouze left for Europe in 1841. On his return in 1843, Rouchouze, 7 priests, seven lay brothers and 10 religious perished when their ship, the Marie-Joseph was lost at sea near the Falklands. Cyprien Liausu became superior of the mission of Our Lady of Peace in the Gambiers, where he remained until 1855.

In 1848, Bishop Jaussen, sent Laval to the Tuamotu Archipelago, where he remained for three years. He returned to the Gambiers in 1851.

Political conflicts

Blackbirders

King Maputeoa died in 1857, and Queen Maria Eutokia became regent on behalf of her ten-year-old son Joseph Gregorio II. Slave ships began to appear starting in 1862. In a practice known as blackbirding, Peruvian and Chilean ships combed the smaller islands of Polynesia seeking workers to fill the extreme labour shortage in Peru. The Serpiente Marina out of Lima, anchored off Mangareva Island on 28 October, ostensibly on a scientific voyage. When local beachcomber-trader Jacques Guilloux went aboard and notice certain peculiarities such as iron grilles on the hatches and concealed daggers on the Captain and supercargo, he told Father Laval that he thought the ship was a slaver, and Laval advised the Queen. When the captain and two others paid a visit to the Queen, she had them arrested. Fearing repercussions from the French authorities in Tahiti, Laval had them released and ordered them to leave the Gambiers. Captain Martinez advised Laval that he intended to file a formal complaint against Guillous, Laval, and the Queen with the French authorities in Peru.[8] Nonetheless, the exodus of young men on transient ships further reduced the population.

Pearl traders

Traders were also attracted to the islands in search of mother of pearl. By 1838 they are complaining that with the presence of the missionaries, they are no longer able to exchange useless items for pearls. As the missionaries made the people aware of the value of their nacre, the Mangarevans monitored more closely the operations in their lagoon.[5] Increased contact with the outside brought exposure to infectious disease. The islands began to be slowly depopulated by pulmonary illnesses, smallpox, and dysentery.[9] An 1871 census by a French army doctor listed the population as 936.[4]

Pignon-Dupuy incident

A conflict arose between a French businessman, Jean Pignon, and the Mangareva local court. Pignon, a former sailor, moved to Mangareva to trade in nacre. His nephew, Jean Dupuy, joined him in 1858. Dupuy refused to sign the recognition of local laws, and was subsequently convicted of adultery and theft. Sentenced to fifteen months, he served two and returned to Valparaiso.

Pignon, who was heavily in debt in Tahiti, began to have difficulties with his landlord in Mangareva. The Mangareva Joint Council authorized the landlord to evict Pignon, and after re-locating his goods, demolish his hut. Pignon complained to M. Roncière, Governor in Tahiti since 1864, who imposed a fine of 160,000 francs on the Regent Maria-Eutokia Toaputeitou, for having ruined Pignon by expropriating and demolishing the hut. The governor then installed the anti-clerical Caillet and twenty soldiers in the Gambiers to collect the fine. Garrett describes the conflict between Laval and the French troops as "a duel between barracks behavior and conventual customs".[10] Governor Roncière tells Laval, "Your population is too religious; your people are stupid."[5]

The dispute becomes an excuse to enhance French power in the archipelago and limit the influence of Laval and the mission. Peace is restored when, at the suggestion of Admiral Rigault de Genouilly, Bishop Florentin-Étienne Jaussen, Apostolic Vicar of Tahiti offers to pay the fine on condition that the soldiers are withdrawn.[1] Jaussen negotiates the amount with Roncière, who agrees to accept 4,300 francs, which "curiously corresponded exactly to the amount that Pignon owed creditors Daniel Guilloux and Augustin Rapamoa.[5]

The Protectorate

As early as 1842 Laval protested French occupation of the Marquesas. As Queen Maria Eutokia's chief advisor, he fought to preserve Mangarevan autonomy against colonists.[10] In early 1870, Arone Teikatoara, the penultimate Prince Regent of Mangareva, asks the French government to end the protectorate, (which, due to a change in policy, had never received formal approval by the French government). The government attributed the request to the influence of Laval, who was viewed as "isolated from the world for thirty-six years and carried away by exaggerated religious ideas".[10] French officials sought his removal. Following the visit of the Commander-Motte Rouge in February 1871 and upon the intervention of Admiral Lapelin, in March 1871, in order to appease Paris and "still this storm",[10] Bishop Jaussen transferred Laval to Papeete, Tahiti and named him his pro-vicar, later making him Vice Provincial.[1][5]

Final years and death

Around the 1870s, Laval collobrated with Father Tiripone Mama Taira Putairi, the first indigenous Mangarevan ordained a Catholic priest, to write a traditional history of Mangareva. The work titled E atoga no te ao eteni no Magareva (An Account of the Heathen Times of Mangareva) was deposited in the archives at the Congregation of the Sacred Heart at Braine-le-Comte, Belgium.[11]

Laval returned to the Gambier Islands, in July 1876, for one last time during a jubilee. His visit was the occasion of a great demonstration of esteem and gratitude. His last years were rather lonely, isolated by increasing deafness. "I can no longer preach, hear confessions anymore, nor enjoy the conversation of others."[1]

Father Honoré Laval died on 1 November 1880, and his body rests in the cemetery of the Catholic mission in Papeete.

Character

Laval did not have the diplomacy of Bishop Florentin-Étienne Jaussen. Fr. Caret found him too "impatient" in their tour of Tahiti in 1836. Fr. Liausu regretted he seemed too severe.[5] Laval was both paternalistic and very strict towards his flock, but equally zealous to protect them from exploitation, both economic and physical, on the part of the traders and sailors who came to frequent the area.[10] A company could lose its contract for pearl-shell if a captain sailed off with a woman without first marrying her.[9]

According to John Garrett, "Laval incarnated the role of guardian, loved by many of the faithful, loathed by his irate opponents."[10]

Legacy

Laval lived in the Gambier Islands for almost forty years and compiled a detailed account of the indigenous peoples, including a grammar of the Mangarevan language, written between 1844 and 1846. He also recorded a local process for determining the solstice.[12] "His grammar, dictionary, and description of Mangareva's pre-Christian culture reveal a classically trained observer affectionately at work."[10] Laval is recognized as a noted ethnologist for his work in recording the Mangarevan customs and practices. However, at the same time he was documenting their culture the missionaries were drastically changing it. The Picpus priests not only introduced a new religion, but European crops, and trained the people in new trades such as carpentry, masonry, and weaving.

The first use of the name of Rapa Nui is in an 1863 letter of Father Laval.[13]

Works

- Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de Mangareva, ère chrétienne, 1834-1871

- Mangareva : l'histoire ancienne d'un peuple polynésien.

- Essai de grammaire Mangarevienne

Controversy

In 1870 an article was published in the Pall Mall Gazette severely criticizing Laval and his fellow priests working in the Gambiers and Tahiti. The story was picked up by other papers, including the Wellington Independent, which on 10 May 1870 ran a story under the title Theocracy in the Pacific. The original account was apparently based on an 1869 pamphlet written by a French former judge in Tahiti, one M. Louis Jacolliot, in defense of the former Governor Count de la Ronciere, who had been accused of abuse of his authority. The pamphlet "La verité sur Tahiti" (The Truth about Tahiti), accused Laval, among other things, of being a poisoner and a murderer.[14] It also apparently made various accusations against Queen Maria Eutokia of Mangareva.

On 31 December 1872, the Independent published a letter referencing a story in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro reporting that Laval had taken the matter to the Supreme Court of the State of the Protectorate of he Society Islands. The court found Jacolliot guilty of defamation,[15] and ordered him to pay 15,000 francs in damages. It ordered the suppression of those portions of the pamphlet deemed defamatory, and further ordered that the judgement be printed in the official journal of the Protectorate in French, English, and Tahitian, as well as, in three newspapers of the French colonies, three journals of Paris, and four gazettes of provinces of Laval's choosing.[14]

Among the accusations levelled by Jacolliot against Laval were:

- that the priests of the Gambiers held a monopoly of the nacre trade and forced the local people to work for them. However, Jean Paul Chopard, in his rebuttal, produced statements from five respected traders who had worked the area for twenty-five years, declaring that they had never observed any of the missionaries engaged in trade.[16]

- that anonymous sources had informed him that Laval had poisoned, (among others), the young King Gregorio, although the king had in fact died of phthisis after a long illness.[16]

- that the Mangarevans wanted a French warship to come and remove Laval, but Chopard presented a document signed by fifteen residents to the contrary.[16]

- that Laval refused to allow shipwrecked Chilean sailors to land, thus forcing them to spend another twenty days at sea in a boat to get to Tahiti. According to Chopard's account, this was Captain W. Clark's Gleaner, which wrecked off Akamaru on the evening of 18 April 1859. The people of the island managed to rescue the crew, passengers, much of their effects, and attempted to right the vessel. Laval offered them the hospitality of the rectory and the sacramental wine for their fatigue. They returned to Tahiti aboard the Queen's schooner Marie-Louise.[16]

Louis Jacolliot

Jacolliot was a French barrister, colonial judge, prolific author and lecturer with an interest in occultism, who lived for several years in Tahiti and India during the period 1865-1869. He believed that the account in the Gospels is a myth based on the mythology of ancient India. His writings on the "Indian roots of western occultism" make reference to an otherwise unknown Sanskrit text he called Agrouchada-Parikchai, which is apparently Jacolliot's personal invention, a "pastiche" of elements taken from Upanishads, Dharmashastras and "a bit of Freemasonry".[17] Jacolliot also believed in a lost Pacific continent, and was quoted on this by Madame Blavatsky.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Mark, André. "La mission aux Îles Gambier"

- 1 2 Lal, Brij V. and Fortune, Kate. "Honoré Laval", The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, University of Hawaii Press, 2000 ISBN 9780824822651

- 1 2 Wiltgen, Ralph M., "The Picpus Missionaries Reach the Gambier Islands", The Founding of the Roman Catholic Church in Oceania, 1825 to 1850, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010 ISBN 9781608995363

- 1 2 Rencsh, Karl. "Early European Influence on the languages of Polynesia: The Gambier Islands", Language Contact and Change in the Austronesian World, (Tom Dutton and Darrell T. Tryon, eds.), p. 484, Walter de Gruyter, 1994 ISBN 9783110883091

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hodeé, Paul. "Catholic Influence in the Islands", Tahiti 1834-1984

- ↑ "Bio-bibliographie C". Paroisse de la Cathédrale de Papeete. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Scott, L., "French Agressions in the Pacific", The Foreign Quarterly Review, Vol. 34, 1844

- ↑ Maude, H. E. (1981). Slavers in Paradise. Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies

- 1 2 Scarr, Deryck. A History of the Pacific Islands, Routledge, 2013 ISBN 9781136837890

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Garrett, John. To Live Among the Stars: Christian Origins in Oceania, World Council of Churches ISBN 9782825406922

- ↑ Buck, Peter Henry (1938). Ethnology of Mangareva. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin. 157. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum Press. p. 13.

- ↑ Ruggles, Clive L. N., Ancient Astronomy, ABC-CLIO, 2005 ISBN 9781851094776

- ↑ Fischer, Steven Roger. "The Naming of Rapanui", Easter Island Studies: Contributions to the History of Rapanui in memory of William T. Mulloy, (Oxford: Oxbow, 1993)

- 1 2 "Father Honore Laval and His Fellow-Laborers in the Pacific", Wellington Independent, Volume XXVII, Issue 3692, 31 December 1872, p. 3

- ↑ Messenger of Tahiti 18 May 1872

- 1 2 3 4 Chopard, Jean Paul. Les Iles Gambier et la brochure de M. L. Jacolliot, Brest,France: J.B. Lefournier Ainé, 1871

- ↑ Introduction to Occult Science in India by Louis Jacolliot [1919] at sacred-texts.com by J. B. Hare, June 21, 2008.

Further reading

- Gillespie, Rosemary G. Clague, D. A., Encyclopedia of Islands, Berkeley, California, University of California Press, p. 635 2009 ISBN 0520256492

- *Stanley, David. Tahiti-Polynesia Handbook, Chico, California, Moon Publications, p. 193, 1989 ISBN 0918373336

External links

Media related to Honoré Laval at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Honoré Laval at Wikimedia Commons