Hobart coastal defences

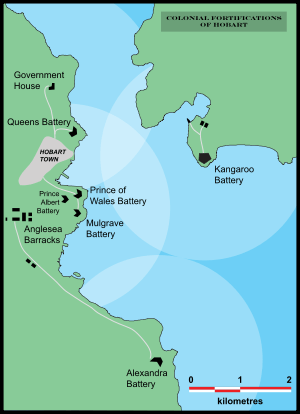

The Hobart coastal defences are a network of now defunct coastal batteries, some of which are inter-linked with tunnels, that were designed and built by British colonial authorities in the nineteenth century to protect the city of Hobart, Tasmania, from attack by enemy warships. During the nineteenth century, the port of Hobart Town was a vital re-supply stop for international shipping and trade, and therefore a major freight hub for the British Empire. As such, it was considered vital that the colony be protected. In all, between 1804 and 1942 there were 12 permanent defensive positions constructed in the Hobart region.[1]

Prior to Australian Federation, the island of Tasmania was a colony of the British Empire, and as such was often at war with Britain's enemies and European rivals, such as France and later Russia. The British had already established the colony of Sydney at Port Jackson in New South Wales in 1788, but soon began to consider the island of Tasmania as the potential site of a useful second colony. It was an island, cut off from the mainland of Australia and isolated geographically, making it ideal for a penal colony, and was rich in timber, a resource useful to the Royal Navy.[2] In 1803, the British authorities decided to colonise Tasmania, and to establish a permanent settlement on the island that was at the time known as Van Diemen's Land, primarily to prevent the French from doing so. During this period tensions between Great Britain and France remained high. The two nations had been fighting the French Revolutionary Wars with each other through much of the 1790s, and would soon be engaging each other again in the Napoleonic Wars.[3]

The first British settlement in Van Diemen's Land had begun on 8 September 1803, at Risdon Cove on the Derwent River's eastern shore. However, the arrival of Lieutenant-Governor David Collins on 16 February 1804, saw him make the decision to relocate the settlement to Sullivan's Cove on the western shore of the Derwent River. Within days of the settlement's establishment, Collins had decided the new colony would need protection should the French send warships up the river to threaten the fledgling colony.[2] A crude earthwork redoubt was dug into an elevated position near the centre of Sullivan's Cove, in the area that is now Franklin Square, and two ships cannons were placed inside. For the next seven years, this muddy emplacement would serve as the only defensive position of what was growing to become Hobart Town.[4]

When Governor Lachlan Macquarie toured the Hobart Town settlement in 1811, he was alarmed at the poor state of the defences and the general disorganisation of the colony. Along with planning for a new grid pattern of streets to be laid out, and new administrative and other buildings to be built, he commissioned the building of Anglesea Barracks, which opened in 1814, and is now the oldest continually occupied barracks in Australia. Macquarie also suggested the construction of more permanent fortifications.[2] Following his advice, a new location comprising an area of 8 acres (32,000 m2) was selected at the eastern end of Battery Point on the southern side of Sullivan's Cove, and construction began on what was to become the first of a series of new defensive installations.

Mulgrave Battery

By 1818, the new battery had been completed on a location in Battery Point near the present Castray Esplanade, and was named Mulgrave Battery in honour of Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave, who was at that time Master-General of the Ordnance. The battery had six guns which projected forward through earthwork embrasures. At first, these were ships guns, but in 1824 they were replaced with 32 pounders.[5] Now Hobart Town had two firing positions protecting either side of the entrance to Sullivans Cove.

Upon its completion, the Mulgrave Battery soon attracted heavy criticism from those who had to serve there. Members of the Royal Artillery felt it was inadequate, and one critic is even said to have described the battery as "a poor pitiful mud fort."[4] Engineers reported that the gun carriages were a danger to men firing the guns, and so new timber was sent from Macquarie Harbour in 1829 to make them safer; however, records showed that only one gun had been upgraded by 1831. The same year, the galleries were improved with large 15 metre long sections of timber, heavy bolts, braces and bars.[6]

As the colony began to grow larger, more British units were sent to serve in the settlement of Hobart Town. Amongst one of these contingents was a commander of the Royal Engineers named Captain Roger Kelsall, who arrived in Hobart in 1835 to take over HM Ordnance Department.[7] When he arrived, he assessed these two fortifications, and wrote in his report that he felt the colony was virtually undefended.[4] He devised an ambitious plan to fortify the whole inner harbour of the Derwent River with a network of heavily armed and fortified batteries located at Macquarie Point, Battery Point and Bellerive Bluff on the eastern shore. He envisaged the forts all having an interlocking firing arc, which would cover the entire approach to Sullivan's Cove, making it impossible for ships to enter the docks or attack the town unchallenged.

The scale of the plan was enormous for such a small colony, the population being approximately 20,000 in the 1830s.[8] This meant that the cost was too prohibitive, considering that at that period the British Empire enjoyed relative peace with the exception of border conflicts in India. Nevertheless, despite funding problems, work using convict labour began in 1840. Mulgrave Battery was enhanced and expanded, and a new site was located slightly further up the hillside on Battery Point, behind the location of the Mulgrave Battery, where construction also commenced in 1840.[9] A semaphore station, built in 1829, and signal mast were constructed above Mulgrave Battery, allowing communication with ships entering the mouth of the river, and through a relay system of masts, all the way to Port Arthur penitentiary on the Tasman Peninsula.[10]

The modern Hobart suburb of Battery Point takes its name from the Mulgrave Battery. The original guardhouse, built in 1818 which had been located nearby is the oldest building in Battery Point, and one of the oldest buildings still standing in Tasmania.[11]

Prince of Wales Battery and Albert Battery

The new battery, named the "Prince of Wales Battery", was completed in 1842. That year ten new 8-inch (200 mm) muzzle loading cannons were lifted into position, enhancing the firepower of the colony's defences. Despite its significant firepower, the poor location and firing angles of the new fortress soon became obvious. The powder magazine was fitted out in 1845.

The layout of the fortifications continued to have the Mulgrave and Prince of Wales batteries to the south of Sullivan's Cove and the Queen's Battery to the north, until the outbreak of the Crimean War with the Russian Empire. Fear of attack or even invasion by Russian warships of the Imperial Russian Navy, which were known to sail in the South Pacific, led to calls for review of Hobart Town's defences. A commission was called and it found that further strengthening was needed. With the problems of the Prince of Wales Battery, it was decided a third battery, the Albert Battery (originally called Prince Albert's Battery after HRH Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's Prince Consort), would be constructed even further up the hill, behind the Prince of Wales Battery.

By 1855, the colony of Van Diemen's Land was granted responsible self-government by the Colonial Office, and renamed Tasmania. The Colonial Office began to pressure the newly formed local government to take more responsibility for the self-defence of the colony.

As a result of these calls, the Tasmanian colonial government began to establish Volunteer Local Militia Forces. One such force, established in 1859 was the Hobart Town Artillery Company under the command of Captain A. F. Smith, formerly of the 99th. (Wiltshire) Regiment, who began to assume responsibility for the Hobart fortifications from the Royal Artillery who were increasingly being withdrawn, and had all departed well before the withdrawal of the last British forces from Tasmania in 1870. Prior to this, in 1868 a Defence Proposals paper had been published which outlined the need for greater defensive fortifications. It also suggested the need for proposed batteries further to the south of Hobart Town on either side of the river.

Improvements to ship's armaments meant that the existing fortifications, which provided covering fire to a range of approximately 2,000 yards (2,000 m), would allow enemy ships to ship outside the range of the defenders guns and still be able to bombard the town. This left the colony virtually defenceless.[12]

Three Imperial Russian Navy warships, the Africa, Plastun, and Vestnik, arrived in January 1882. Britain and its empire had fought against the Russians 26 years previously during the Crimean War and the colony was virtually defenceless. The Russians were on a goodwill mission, but had they had hostile intent, the colony would have easily fallen. As a result, the visit caused a great deal of debate about the state of the colony's defences.[13][14]

It had also highlighted the state of decay the existing fortresses had reached. Another Commission was carried out, and it was decided the Mulgrave, Prince of Wales and Albert Batteries were inadequate for the defence of the town. By 1878, both had been condemned, and were dismantled by 1880. In 1882, the sites were handed over to Hobart City Council for use as public space, although the subterranean Prince of Wales magazine remains. Most of the stonework was removed and reused in the construction of the Alexandra Battery further to the south.[15]

Following the closures, the entrance to the old magazine soon became a popular place for children to play, and at night, the underground magazine rooms often became a meeting place for men to drink and play cards, until they were closed and kept permanently locked by the council in 1934.[4]

To this day, the park in which the Mulgrave, Prince of Wales and Albert Batteries had been located remains a popular public park, and is named Princes Park in honour of the men who served in the batteries there, and as a reminder of the heritage of the site. The iron gate at the entrance of the underground magazine rooms can still be seen at the base of the park.[15]

Queen's Battery

As part of Major Roger Kellsall's recommendations, another site to the north-eastern side of Hobart Town was to be used for an additional fortification. This site, located almost exactly underneath the present site of the Hobart Cenotaph war memorial upon Queens Domain was first constructed in 1838 and opened the same year as Queen's Battery, named in honour of HRH Queen Victoria, who was on the throne at the time of the fort's construction. It had been envisaged that this would be the grandest of the forts in Hobart, and would command the prominent point overlooking the entrance to Sullivans Cove; however, the full plans were never developed. The battery was set back by delays and funding problems, and was not completed until 1864.[16]

With the imminent withdrawal of British forces due in 1870, a major review of defences had been carried out in 1868. It was decided the current system was inadequate to cope with advances in naval ordnance, and two new forts would be positioned at One Tree Point and Bellerive Bluff. The Queen's Battery was to assume the apex position of a triangular coverage of the entrance to Sullivans Cove.

As the Royal Artillery were to withdraw within two years, a handbook containing range tables was created by Staff-Sergeant R.H. Eccleston which suggested that to repel a vessel doing 10 knots (19 km/h) up the river would take 226 men approximately 30 minutes to fire 365 rounds from the 20 guns that were available from the existing three forts.[17] Despite this, it became an operational position, and for a time served as an effective defence. The Queen's Battery remained in operation until the 1920s. The excavation of the site in 1992 revealed the hot shot oven which was uncovered and metal parts for rolling the shot which had been preserved. The oven and archaeological trenches were later filled in at the request of the Returned and Services League (RSL). Hot shot was intended to be fired at wooden ships and to cause ignition of gunpowder. It was never fired in anger.

Alexandra Battery

Following the condemnation of the Mulgrave, Prince of Wales, and Albert batteries in 1878, it was decided to re-institute the plans for the alteration of the defensive strategy around the entrance to Sullivans Cove that were first drawn up in 1868.[16]

A triangle of fortresses with the Queen's Battery at the Apex, and two new batteries, the Alexandra Battery, named for Princess Alexandra, the Princess of Wales, and the Kangaroo Battery on the eastern shore would be adequate for the task. Construction began on the new fortifications in 1880, and at the same time, a new permanent field artillery unit, the Southern Tasmanian Volunteer Artillery equipped with two breech-loading 12-pound howitzers and two 32-pound guns on field carriages, was raised.[17]

Following the dismantling of the Battery Point batteries, much of the stonework was relocated to the Alexandra Battery. The Alexandra Battery site is now a public park with commanding views of the river, and much of the original construction is still accessible.[15]

Kangaroo Battery

The presence of the Russian warships in the Derwent River in 1873,[18] and the condemning of the Battery Point batteries in 1878 had expedited the development of the Alexandra and Kangaroo Batteries.

The design of the fort was a pentagon shape that fitted conveniently into the point of the bluff above the cliff. The ditch, tunnels and underground chambers had to be cut out of solid stone and faced with masonry. Several loopholes and firing ports were fitted into the stone encasements to allow rifle fire from every aspect of the fort. In case of an attempted infantry assault, caponiers faced both landward sides of the fort, with firing positions facing each direction. This meant that the only position to safely assault the fort with infantry was up the sheer cliffs of Kangaroo Bluff. Access to the caponiers was through iron hatchways that opened into open passageways three metres deep. These in turn led to tunnels accessing underground magazines, stores, a lamp room, well and the loading galleries. The loading galleries were ingenious and allowed the guns to be muzzle loaded with shells dragged along a conveyor belt directly to the muzzle of the gun, when it was in a downward tilted position.[12]

Construction of the Kangaroo Battery was begun when excavations began to be dug in September 1880, according to the plans of Colonel Peter Scratchley, a Royal Engineer who had been placed in charge of overseeing construction of defences for all of the Australian colonies.

Work was intermittent and beset by funding problems and delays, but in May 1883, Patrick Cronly was placed in charge of the construction on behalf of the Public Works Department, and under the supervision of Staff Officer Boddam, work was completed the following year with the arrival of two massive 14 tonne eight-inch (203 mm) cannons from England. The construction had cost £8,150 (A$16,300) at a time when labourers earned an average wage of about 4 shillings (50c) per day. The guns fired shells weighing 81.7 kg, and thanks to the barreled rifling, had excellent range and accuracy. In 1888, two smaller QF 6 pounder Nordenfelt guns were added. Although the projectiles were only 2.7 kg, they also had excellent accuracy and range. The same year, a Nordenfelt machine gun was mounted facing the entrance gate of the fort.

The first shots were fired on 12 February 1885. Later that year, a dry mound, and deepened wet moat were added, as was further coarse-work covered in broken bottle glass set in mortar. Fences were constructed around the moat in November 1885 when a local boy fell into the moat and drowned.[12]

From 1887, both the Alexandra and Kangaroo Batteries were being manned by detachments of the Southern Tasmanian Volunteer Artillery, as well as the Tasmanian Permanent Artillery.[17] In 1901 Tasmania joined the new Federation of Australia, and all of the city's fortifications passed into Commonwealth control. Kangaroo Fort remained operational until the 1920s, but never fired a shot in anger. In 1925, all of the guns were buried as obsolete, and in 1930, the Clarence City Council took over the site for use as a public park. In 1961, the Scenery Preservation Board acquired the site, and in 1970, the site was turned into a historical site, with the guns being dug up and put on display. The site is now operated by Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife Service and is a major tourist attraction.

Fort Direction and Pierson's Point

With the outbreak of World War II, the Department of Defence acquired land near South Arm close to the mouth of the Derwent River on the eastern shore, from Courtland Calvert and his sister in September 1939.[1] At first, the land was used purely as a training ground, with mock battles that were disruptive to locals being fought day and night. But as war preparations evolved, the Commonwealth decided that the port of Hobart would require some degree of defence to protect the state's vital zinc industry that was crucial to the war effort. Major Mark Pritchard was the first commanding officer of the new defences that became known as Fort Direction.[1] By the end of 1939, construction of two fortified six-inch (152 mm) Mk VII gun emplacements, and a small four room weatherboard control building had been completed. Soon there was also a flagpole and set of naval signals.[1][19]

Throughout the war, a 24-hour watch was maintained every day, and the site was usually manned by at least 15 Royal Australian Navy personnel. A record of every ship entering the Derwent River between 1940 and 1945 was kept. Between 1941 and 1944, both guns were regularly used for training exercises. Although never used in hostile action against enemy vessels, the guns were fired in anger once. A liberty ship entering the mouth of the Derwent River failed to obey instructions issued from the Naval Command on the hill above the fort, and one shell was accurately fired across her bow, which immediately resulted in the liberty ship hoving to.[1]

On the opposite western shore of the Derwent River, another emplacement was constructed with one four-inch (102 mm) gun. However, several huts to house men were constructed at that location as well as a complicated underground tunnel and command structure. Local residents recall barbed wire still surrounding the site well after the war and the site’s de-commissioning. Nearby Goat Bluff was also the location of further underground tunnel systems.[1]

The only enemy action to ever affect Hobart happened on 1 August 1942, when a submarine-launched Japanese spy plane flew from the submarine’s mooring in Great Oyster Bay south along the east coast of Tasmania, before flying northward along the Derwent River surveying Hobart and then returning to its mother submarine. Although both emplacements detected the flight, the plane was at too high an altitude to fire upon, and no aircraft were available to intercept it. After this event, two anti-aircraft guns were positioned on nearby hills, but the Japanese never returned to Tasmania again during the war.[1]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Potter (2006).

- 1 2 3 Robson (1983).

- ↑ French Revolution (1824).

- 1 2 3 4 Heritage Tasmania (2006).

- ↑ Dollery (1967), pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Engineering Heritage Committee, Tasmania Division (2004).

- ↑ Spratt (1992), p. 97.

- ↑ Bourke, et al. (2006).

- ↑ Dollery (1967), pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Barnard (2012), p. 39.

- ↑ Chapman & Chapman 1996, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Parks & Wildlife Service (2007).

- ↑ Massov (n.d.).

- ↑ The Mercury Newspaper (18 Jan 1882), Hobart. Available: trove.nla.gov.au

- 1 2 3 Hobart City Council, Parks and Gardens (n.d.).

- 1 2 Scripps (1989).

- 1 2 3 Petterwood (n.d.).

- ↑ Dollery (1967), p. 160.

- ↑ Horner (1995), p. 218.

References

- Barnard, Edwin. Capturing Time: Panoramas of Old Australia. Canberra: National Library Australia. ISBN 9780642277503.

- Bourke, John, Lucadou-Wells, Rosemary (October 2006). "Commerce and Public Water Policy: The Case of Hobart Town Van Diemen's Land 1804–1881" (PDF). International Business Review. 2 (2): 22–44. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Chapman, John; Chapman, Monica (1996). Tasmania. Hawthorne, Victoria: Lonely Planet. ISBN 9780864423849.

- Dollery, E.M. (April 1967). "Defences of the Derwent". Papers and Proceedings. Tasmanian Historical Research Association. 14 (4): 148–164. ISSN 0039-9809.

- Engineering Heritage Committee, Tasmania Division (June 2004). "Engineering Heritage Walk". Institution of Engineers, Australia. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Heritage Tasmania (February 2006). "On the Register: Princes Park, Battery Point" (PDF). Heritage Tasmania. p. 2. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Hobart City Council (n.d.). "Parks and Gardens". Hobart City Council. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- Horner, David (1995). The Gunners. A History of Australian Artillery. Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1863739173.

- Massov, Alexander (n.d.). "The Visit of the Russian Naval Squadron of Admiral Aslanbegov to Australia 1881–1882". Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- Mignet, François (1824). "History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814". Project Gutenburg. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- Parks & Wildlife Service (June 2007). "Guide to Tasmania's Historic Places – Kangaroo Bluff". Department of Tourism, Arts and the Environment. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Petterwood, Graeme (n.d.). "A Tasmanian Gunner's History". Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Potter, Maurice (August 2006). "South Arm: History". Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- Robson, L.L. (1983). A History of Tasmania. Volume 1. Van Diemen's Land from the Earliest Times to 1855. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554364-5.

- Scripps, Lindy (1989). Queen's Battery & Alexandra Battery. Hobart, Tasmania: Parks and Recreation Department. OCLC 220922178.

- Spratt, Peter (5–7 October 1992). "The Tasmanian Royal Engineers Building: The People Who Built it and What They Did - The Good and the Bad - Their Impact on the Building and its Conservation" (PDF). Sixth National Conference on Engineering Heritage. Hobart: Institution of Engineers, Australia, Tasmania Division: 97–100. ISBN 9780858255678.

Further reading

- MacFie, Peter (1986). "The Royal Engineers in Colonial Tasmania". Historic Environment. 5 (2): 4–14. ISSN 0726-6715.

- McNicoll, Ronald (1977). The Royal Australian Engineers 1835 to 1902: The Colonial Engineers. History of the Royal Australian Engineers. Volume I. Canberra: Australian Capital Territory: Corps Committee of the Royal Australian Engineers. ISBN 9780959687118.

Coordinates: 42°53′33″S 147°20′03″E / 42.892504°S 147.33417°E