History of Shetland

The History of Shetland concerns the subarctic archipelago of Shetland in Scotland. The early history of the islands is dominated by the influence of the Vikings and from the 14th century on by the relationship with the Kingdom of Scotland, and then latterly as part of the United Kingdom.

Prehistory

Due to building in stone on virtually treeless islands—a practice dating to at least the early Neolithic Period—Shetland is extremely rich in physical remains of the prehistoric eras and there are over 5,000 archaeological sites all told.[2] A midden site at West Voe on the south coast of Mainland, dated to 4320–4030 BC, has provided the first evidence of Mesolithic human activity on Shetland.[3][4] The same site provides dates for early Neolithic activity and finds at Scourd of Brouster in Walls have been dated to 3400 BC.[Note 1] "Shetland knives" are stone tools that date from this period made from felsite from Northmavine.[6]

Viking expansion

The image is from the Icelandic manuscript Flateyjarbók from the 15th century.

By the end of the 9th century the Scandinavians shifted their attention from plundering to invasion, mainly due to the overpopulation of Scandinavia in comparison to resources and arable land available there.[7]

Shetland was colonised by Norsemen in the 9th century, the fate of the existing indigenous population being uncertain. The colonisers gave it that name and established their laws and language. That language evolved into the West Nordic language Norn, which survived into the 19th century.

After Harald Finehair took control of all Norway, many of his opponents fled, some to Orkney and Shetland. From the Northern Isles they continued to raid Scotland and Norway, prompting Harald Hårfagre to raise a large fleet which he sailed to the islands. In about 875 he and his forces took control of Shetland and Orkney. Ragnvald, Earl of Møre received Orkney and Shetland as an earldom from the king as reparation for his son's being killed in battle in Scotland. Ragnvald gave the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.

Shetland was Christianised in the 10th century.

Conflict with Norway

In 1194 when king Sverre Sigurdsson (ca 1145–1202) ruled Norway and Harald Maddadsson was Earl of Orkney and Shetland, the Lendmann Hallkjell Jonsson and the Earl's brother-in-law Olav raised an army called the eyjarskeggjar on Orkney and sailed for Norway. Their pretender king was Olav's young foster son Sigurd, son of king Magnus Erlingsson. The eyjarskeggjar were beaten in the Battle of Florvåg near Bergen. The body of Sigurd Magnusson was displayed for the king in Bergen in order for him to be sure of the death of his enemy, but he also demanded that Harald Maddadsson (Harald jarl) answer for his part in the uprising. In 1195 the earl sailed to Norway to reconcile with King Sverre. As a punishment the king placed the earldom of Shetland under the direct rule of the king, from which it was probably never returned.

Increased Scottish interest

When Alexander III of Scotland turned twenty-one in 1262 and became of age he declared his intention of continuing the aggressive policy his father had begun towards the western and northern isles. This had been put on hold when his father had died thirteen years earlier. Alexander sent a formal demand to the Norwegian King Håkon Håkonsson.

After decades of civil war, Norway had achieved stability and grown to be a substantial nation with influence in Europe and the potential to be a powerful force in war. With this as a background, King Håkon rejected all demands from the Scots. The Norwegians regarded all the islands in the North Sea as part of the Norwegian realm. To add weight to his answer, King Håkon activated the leidang and set off from Norway in a fleet which is said to have been the largest ever assembled in Norway. The fleet met up in Breideyarsund in Shetland (probably today's Bressay Sound) before the king and his men sailed for Scotland and made landfall on Arran. The aim was to conduct negotiations with the army as a backup.

Alexander III drew out the negotiations while he patiently waited for the autumn storms to set in. Finally, after tiresome diplomatic talks, King Håkon lost his patience and decided to attack. At the same time a large storm set in which destroyed several of his ships and kept others from making landfall. The Battle of Largs in October 1263 was not decisive and both parties claimed victory, but King Håkon Håkonsson's position was hopeless. On 5 October, he returned to Orkney with a discontented army, and there he died of a fever on 17 December 1263. His death halted any further Norwegian expansion in Scotland.

King Magnus Lagabøte broke with his father's expansion policy and started negotiations with Alexander III. In the Treaty of Perth of 1266 he surrendered his furthest Norwegian possessions including Man and the Sudreyar (Hebrides) to Scotland in return for 4,000 marks sterling and an annuity of 100 marks. The Scots also recognised Norwegian sovereignty over Orkney and Shetland.

One of the main reasons behind the Norwegian desire for peace with Scotland was that trade with England was suffering from the constant state of war. In the new trade agreement between England and Norway in 1223 the English demanded Norway make peace with Scotland. In 1269, this agreement was expanded to include mutual free trade.

Pawned to Scotland

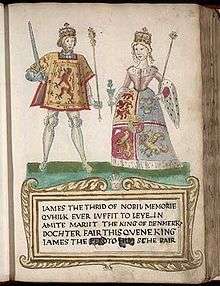

In the 14th century Norway still treated Orkney and Shetland as a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing, and in 1379 the Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson.[8] In 1348 Norway was severely weakened by the Black Plague and in 1397 it entered the Kalmar Union. With time Norway came increasingly under Danish control. King Christian I of Denmark and Norway was in financial trouble and, when his daughter Margaret became engaged to James III of Scotland in 1468, he needed money to pay her dowry. Under Norse udal law, the king had no overall ownership of the land in the realm as in the Scottish feudal system. He was king of his people, rather than king of the land. What the king did not personally own was owned absolutely by others. The King's lands represented only a small part of Shetland.[9] Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Riksråd (Council of the Realm) he entered into a commercial contract on 8 September 1468 with the King of Scots in which he pawned his personal interests in Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilders.[10] On 28 May the next year he also pawned his Shetland interests for 8,000 Rhenish guilders.[11] He secured a clause in the contract which gave Christian or his successors the right to redeem the islands[12] for a fixed sum of 210 kilograms (460 lb) of gold or 2,310 kilograms (5,090 lb) of silver. There was an obligation to retain the language and laws of Norway, which was not only implicit in the pawning document, but is acknowledged in later correspondence between James III and King Christian’s son John (Hans).[13] In 1470 William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness ceded his title to James III and on 20 February 1472, the Northern Isles were directly annexed to the Crown of Scotland.[14]

James and his successors fended off all attempts by the Danes to redeem them (by formal letter or by special embassies were made in 1549, 1550, 1558, 1560, 1585, 1589, 1640, 1660 and other intermediate years) not by contesting the validity of the claim, but by simply avoiding the issue.[15]

Hansa era

From the early 15th century on the Shetlanders sold their goods through the Hanseatic League of German merchantmen. The Hansa would buy shiploads of salted fish, wool and butter and import salt, cloth, beer and other goods. The late 16th century and early 17th century was dominated by the influence of the despotic Robert Stewart, Earl of Orkney, who was granted the islands by his half-sister Mary Queen of Scots, and his son Patrick. The latter commenced the building of Scalloway Castle, but after his execution in 1609 the Crown annexed Orkney and Shetland again until 1643 when Charles I granted them to William Douglas, 7th Earl of Morton. These rights were held on and off by the Mortons until 1766, when they were sold by James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton to Sir Laurence Dundas.[16][17]

British era

The trade with the North German towns lasted until the 1707 Act of Union prohibited the German merchants from trading with Shetland. Shetland then went into an economic depression as the Scottish and local traders were not as skilled in trading with salted fish. However, some local merchant-lairds took up where the German merchants had left off, and fitted out their own ships to export fish from Shetland to the Continent. For the independent farmers of Shetland this had negative consequences, as they now had to fish for these merchant-lairds.[18] With the passing of the Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886 the Liberal prime minister William Ewart Gladstone emancipated crofters from the rule of the landlords. The Act enabled those who had effectively been landowners' serfs to become owner-occupiers of their own small farms.[19][20]

During the 200 years after the pawning the islands were passed back and forth fourteen times between the Crown and courtiers as a means of extracting income. Laws were changed, weights and measures altered and the language suppressed, a process historians now call "feudalization" as a means by which Shetland supposedly became incorporated into Scotland, particularly during the 17th century. The term is a nonsense because a feudal charter requires ownership by the Crown[21] - ownership it has never had and has never openly claimed to have had. As late as the 20th century the courts declared that no land in Shetland was under feudal tenure.[22]

The Crown might have thought that by prescription (the passage of time) it gave them ownership necessary to give out feudal charters, grants, or licences. It certainly behaved that way. Nevertheless, this was proved wrong by the Treaty of Breda (1667). Its direct concern was the redistribution of colonial lands throughout the world after the second Anglo-Dutch war. It was signed by ‘the plenipotentiaries of Europe’ - delegations having full government power.

The Danish delegation tried to have a clause inserted to have the islands returned without delay. Because the overall treaty was too important to Charles II he eventually conceded that the original marriage document still stood, that his and previous monarchs’ actions in granting out the islands under feudal charters were illegal.

In 1669 Charles passed his 1669 Act for annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the Crown, restoring the situation much as it had been in 1469. He abolished the office of Sheriff and ‘erected Shetland into a Stewartry’, having ‘a direct dependence upon His Majesty and his officers’ (what today we would today call a Crown Dependency)[Note 2]. Charles II also provided that, in the event of a ‘general dissolution of his majesty’s properties’ by which he clearly meant the Act of Union, Shetland was not to be included. Shetland could not be incorporated into the realm of Scotland or the proposed new union with England. The terms of the marriage document also meant that any Acts of Parliament before or after the pawning could have had no relevance to Shetland.

With the consent of Parliament, Charles was taking the exclusive rights to the islands back to the Crown for all time coming. Furthermore, he was specifically excluding Shetland from the coming Act of Union, even going so far as to say that the Act of Union itself would be null and void if Shetland were to be included.

Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success.[23] Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by a Scottish Act of Parliament on 27 December 1669 which officially made the islands a Crown dependency and exempt from any "dissolution of His Majesty’s lands". In 1742 a further Act of Parliament returned the estates to a later Earl of Morton, although the original Act of Parliament specifically ruled that any future act regarding the islands status would be "considered null, void and of no effect".

Nonetheless, Shetland's connection with Norway has proven to be enduring. When Norway became independent again in 1906 the Shetland authorities sent a letter to King Haakon VII in which they stated: "Today no 'foreign' flag is more familiar or more welcome in our voes and havens than that of Norway, and Shetlanders continue to look upon Norway as their mother-land, and recall with pride and affection the time when their forefathers were under the rule of the Kings of Norway."[24]

Napoleonic wars

Some 3000 Shetlanders served in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars from 1800 to 1815.[25]

World War II

During World War II a Norwegian naval unit nicknamed the "Shetland Bus" was established by the Special Operations Executive Norwegian Section in the autumn of 1940 with a base first at Lunna and later in Scalloway in order to conduct operations on the coast of Norway. About 30 fishing vessels used by Norwegian refugees were gathered in Shetland. Many of these vessels were rented, and Norwegian fishermen were recruited as volunteers to operate them.

The Shetland Bus sailed in covert operations between Norway and Shetland, carrying men from Company Linge, intelligence agents, refugees, instructors for the resistance, and military supplies. Many people on the run from the Germans, and much important information on German activity in Norway, were brought back to the Allies this way. Some mines were laid and direct action against German ships was also taken. At the start the unit was under a British command, but later Norwegians joined in the command.

The fishing vessels made 80 trips across the sea. German attacks and bad weather caused the loss of 10 boats, 44 crewmen, and 60 refugees. Because of the high losses it was decided to procure faster vessels. The Americans gave the unit the use of three submarine chasers (HNoMS Hessa, HNoMS Hitra and HNoMS Vigra). None of the trips with these vessels incurred loss of life or equipment.[26]

The Shetland Bus made over 200 trips across the sea and the most famous of the men, Leif Andreas Larsen (Shetlands-Larsen) made 52 of them.[27]

Cultural influences

Historical, archaeological, place-name and linguistic evidence indicates Norse cultural dominance of Shetland during the Viking period.[28] A few place names might have Pictish origin, but this is disputed. Several genetic studies have been conducted investigating the genetic makeup of the islands' population today in order to establish its origin. Shetlanders are less than half Scandinavian in origin. They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives.[29] After the islands were transferred to Scotland thousands of Scots families emigrated to Shetland in the 16th and 17th centuries. Contacts with Germany and the Netherlands through the fishing trade brought smaller numbers of immigrants from those countries. World War II and the oil industry have also contributed to population increase through immigration.[18]

Population development

The population development on Shetland has through the times been affected by deaths at sea and epidemics. Smallpox afflicted the islands in the 17th and 18th centuries, but as vaccines became common after 1760 the population increased to 40,000 in 1861. The population increase led to a lack of food and many young men went away to serve in the British merchant fleet. 100 years later the islands' population was more than halved. This decrease was mainly caused by the large number of Shetlandic men being lost at sea during the two world wars and the waves of emigration in the 1920s and 1930s. Now more people of Shetlandic background live in Canada, Australia and New Zealand than in Shetland.

| District | Population 1961 | Population 1971 | Population 1981 | Population 1991 | Population 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bound Skerry (& Grunay) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bressay | 269 | 248 | 334 | 352 | 384 |

| Bruray | 34 | 35 | 33 | 27 | 26 |

| East Burra | 92 | 64 | 78 | 72 | 66 |

| Fair Isle | 64 | 65 | 58 | 67 | 69 |

| Fetlar | 127 | 88 | 101 | 90 | 86 |

| Foula | 54 | 33 | 39 | 40 | 31 |

| Housay | 71 | 63 | 49 | 58 | 50 |

| Mainland | 13,282 | 12,944 | 17,722 | 17,562 | 17,550 |

| Muckle Flugga | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muckle Roe | 103 | 94 | 99 | 115 | 104 |

| Noss | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Papa Stour | 55 | 24 | 33 | 33 | 25 |

| Trondra | 20 | 17 | 93 | 117 | 133 |

| Unst | 1,148 | 1,124 | 1,140 | 1,055 | 720 |

| Vaila | 9 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| West Burra | 561 | 501 | 767 | 817 | 753 |

| Whalsay | 764 | 870 | 1,031 | 1,041 | 1,589 |

| Yell | 1,155 | 1,143 | 1,191 | 1,075 | 957 |

| Total | 17,814 | 17,327 | 22,768 | 22,522 | 22,990 |

Timeline

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 875 | Harald Hårfagre took control of the islands |

| 1195 | Harald Maddadsson lost the earldom of Shetland and the islands are put directly under the Norwegian king Sverre Sigurdsson |

| 1379 | The Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson |

| 1469 | Christian I pawned Shetland to the Scottish king James III for a dowry |

| 1700–1760 | Smallpox hit the islands |

| 18th century | Norn language gradually dies out |

| 1707 | The German merchants lost their trading rights in Shetland |

| 1708 | Capital moved from Scalloway to Lerwick |

| 1880s | William Ewart Gladstone freed the serfs |

| 1940 | Shetland bus established by the Special Operations Executive |

| 1969 | Shetland marks 500 years under both Norwegian and Scottish rule |

| 1975 | Lerwick Town Council and Zetland County Council merged to Shetland Islands Council |

| 1978 | Oil terminal in Sullom Voe opened |

References

- Notes

- ↑ The Scord of Brouster site includes a cluster of six or seven walled fields and three stone circular houses that contains the earliest hoe-blades found so far in Scotland.[5]

- ↑ The Isle of Man is a Crown Dependency. It is one of Her Majesty’s personal dominions, not subject to Acts of the UK Parliament. In Shetland, because it is only in the position of having trusteeship, the Crown has an even weaker hold than it has in the Isle of Man, so a new description would have to be invented.

- Footnotes

- ↑ " Jarlshof & Scatness" shetland-heritage.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ↑ Turner (1998) p. 18

- ↑ Melton, Nigel D. "West Voe: A Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition Site in Shetland" in Noble et al (2008) pp. 23, 33

- ↑ Melton, N. D. & Nicholson R. A. (March 2004) "The Mesolithic in the Northern Isles: the preliminary evaluation of an oyster midden at West Voe, Sumburgh, Shetland, U.K." Antiquity 78 No 299.

- ↑ Fleming (2005) p. 47 quoting Clarke, P.A. (1995) Observations of Social Change in Prehistoric Orkney and Shetland based on a Study of the Types and Context of Coarse Stone Artefacts. M. Litt. thesis. University of Glasgow.

- ↑ Schei (2006) p. 10

- ↑ James Graham-Campbell: Cultural Atlas of the Viking World, 1999. Page 38. ISBN 0-8160-3004-9

- ↑ Julian Richards, Vikingblod, page 235, Hermon Forlag, ISBN 978-82-8320-016-4

- ↑ Ballantyne and Smith, Shetland Documents 1195-1579, "the crown had only a small landed estate in Shetland"

- ↑ Acquisition of Orkney and Shetland 1468-9 or http://web.archive.org/web/20070610085151/http://www.rosslyntemplars.org.uk/orkney&shetland.htm

- ↑ University Library, University in Bergen: Article on Shetland (Norwegian)

- ↑ No original is known to exist: transcript in British Library, Royal Mss., 18.B.vi, p.13. Latin. Printed in NgL, 2nd series, ii, no. 116; based on the translation of B.E. Crawford, ‘The earldom of Orkney and lordship of Shetland: a reinterpretation of their pledging to Scotland in 1468–70’, in Saga-Book, xvii, 1966–69, pp.175–76

- ↑ Edinburgh University Library, Laing MSS, La. Ill - 322, pp 16–17

- ↑ Macdougall, Norman (1982). James III: a political study. J. Donald. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-85976-078-2. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

What James III had acquired from Earl William in return for this compensation was the comital rights in Orkney and Shetland. He already held a wadset of the royal rights; and to ensure his complete control, he referred the matter to parliament. On 20 February 1472 the three estates approved the annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the crown...

- ↑ Gilbert Goudie, The Danish Claims upon Orkney and Shetland, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. 21 p. 245

- ↑ Schei (2006) pp. 14–16

- ↑ Nicolson (1972) pp. 56–57

- 1 2 Visit.Shetland.org history page

- ↑ "A History of Shetland" Visit.Shetland.org

- ↑ McLean, Duncan (20 September 1998) "Getting on the Map". London. The Independent. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ McNeil - Common Law Aboriginal Title, p. 139: "If the Crown grants land where it has neither title nor possession, the grant is simply void." - p. 82: "In common law, if the king was not in possession, he could not grant." - p.93: "For the Crown to be in possession of land its title in most cases must appear as a matter of record." Stair - The Laws of Scotland, Vol 24, p.202: "There can be no proper feudal holding that does not flow from the Crown."

- ↑ Lord Johnson, Lord Advocat v. Balfour, 1907. SC 1360 at 1368.

- ↑ Universitas, Norsken som døde (Norwegian article on the history of the islands) (Norwegian)

- ↑ Schei (2006) p. 13

- ↑ Ursula Smith" Shetlopedia. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ University in Bergen, Historical institute page on the Shetland Gang(Norwegian)

- ↑ Kulturnett Hordaland page on Shetlands-Larsen(Norwegian)

- ↑ Jones G. (1984) A History of the Vikings Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- ↑ Article: Genetic evidence for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods

Further reading

- Coull, James R. "A comparison of demographic trends in the Faroe and Shetland Islands." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (1967): 159-166.

- Miller, James. The North Atlantic Front: Orkney, Shetland, Faroe and Iceland at War (2004)

- Nicolson, James R. (1972) Shetland. Newton Abbott. David & Charles.

- Schei, Liv Kjørsvik (2006) The Shetland Isles. Grantown-on-Spey. Colin Baxter Photography. ISBN 978-1-84107-330-9

- Withrington, Donald J. Shetland and the outside world, 1469-1969. Oxford Univ Pr, 1983.