Harwich

| Harwich | |

Harwich in late-May 2004 |

|

Harwich |

|

| Population | 17,684 (2011)[1] |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | TM243313 |

| District | Tendring |

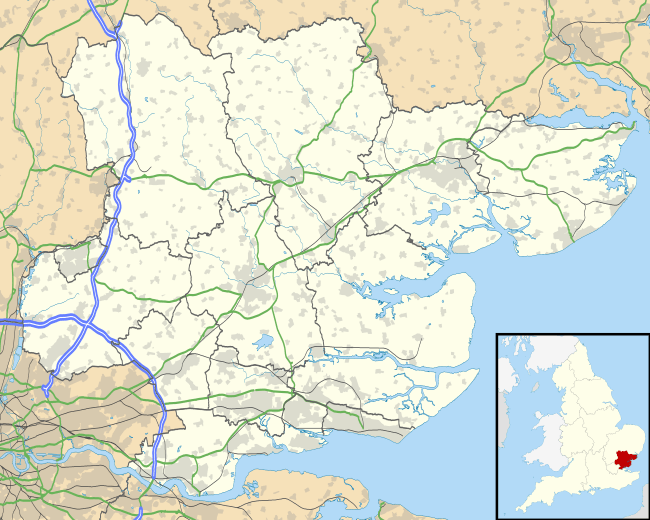

| Shire county | Essex |

| Region | East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HARWICH |

| Postcode district | CO12 5 |

| Dialling code | 01255 |

| Police | Essex |

| Fire | Essex |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| EU Parliament | East of England |

| UK Parliament | Harwich and North Essex |

Coordinates: 51°56′40″N 1°17′23″E / 51.944580°N 1.289852°E

Harwich /ˈhærɪtʃ/ is a town in Essex, England and one of the Haven ports, located on the coast with the North Sea to the east. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the northeast, Ipswich to the northwest, Colchester to the southwest and Clacton-on-Sea to the south. It is the northernmost coastal town within Essex.

Its position on the estuaries of the Stour and Orwell rivers and its usefulness to mariners as the only safe anchorage between the Thames and the Humber led to a long period of maritime significance, both civil and military. The town became a naval base in 1657 and was heavily fortified,[2] with Harwich Redoubt, Beacon Hill Battery, and Bath Side Battery.

Harwich today is contiguous with Dovercourt and the two, along with Parkeston, are often referred to collectively as Harwich.

History

The town's name means "military settlement," from Old English here-wic.[3]

The town received its charter in 1238, although there is evidence of earlier settlement – for example, a record of a chapel in 1177, and some indications of a possible Roman presence.

Because of its strategic position, Harwich was the target for the invasion of Britain by William of Orange on 11 November 1688. However, unfavourable winds forced his fleet to sail into the English Channel instead and eventually land at Torbay. Due to the involvement of the Schomberg family in the invasion, Charles Louis Schomberg was made Marquess of Harwich.[4]

Writer Daniel Defoe devotes a few pages to the town in A tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain. Visiting in 1722, he noted its formidable fort and harbour "of a vast extent".[5] The town, he recounts, was also known for an unusual spring rising on Beacon Hill (a promontory to the north-east of the town), which "petrified" clay, allowing it to be used to pave Harwich's streets and build its walls. The locals also claimed that "the same spring is said to turn wood into iron", but Defoe put this down to the presence of "copperas" in the water. Regarding the atmosphere of the town, he states: "Harwich is a town of hurry and business, not much of gaiety and pleasure; yet the inhabitants seem warm in their nests and some of them are very wealthy".[5]

Royal Naval Dockyard

Harwich Dockyard was established as a Royal Navy Dockyard in 1652. It ceased to operate as a Royal Dockyard in 1713 (though a Royal Navy presence was maintained until 1829). During the Second World War parts of Harwich were again requisitioned for naval use, and ships were based at HMS Badger; Badger was decommissioned in 1946, but the Royal Naval Auxiliary Service maintained a headquarters on the site until 1992.[6]

Port

The Royal Navy is no longer present in Harwich but Harwich International Port at nearby Parkeston continues to offer regular ferry services to the Hook of Holland (Hoek van Holland) in the Netherlands. Many operations of the large container port at Felixstowe and of Trinity House, the lighthouse authority, are managed from Harwich.

The port is famous for the phrase "Harwich for the Continent", seen on road signs and in London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) advertisements.[7][8]

Lighthouses

The Harwich High Lighthouse of 1818 | |

| Location |

Harwich Essex England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°56′40″N 1°17′19″E / 51.944468°N 1.288553°E |

| Year first constructed | 1665 (first) |

| Year first lit | 1818 (current) |

| Deactivated | 1863 |

| Construction | brick tower |

| Tower shape | tapered enneagonal prism with light shown from the top window and tented roof [9] |

| Markings / pattern | unpainted tower |

| Height | 21 metres (69 ft) |

| ARLHS number | ENG-093 |

| Managing agent | The Harwich Society[10] |

At least three pairs of lighthouses have been built over recent centuries as leading lights, to help guide vessels into Harwich. The earliest pair were wooden structures: the High Light stood on top of the old Town Gate, whilst the Low Light (featured in a painting by Constable) stood on the foreshore. Both were coal-fired.

In 1818 these were replaced by stone structures, designed by John Rennie Senior, which can still be seen today (they no longer function as lighthouses: one houses the town's maritime museum, the other is (in 2015) also being converted into a museum).[11] They were owned by General Rebow of Wivenhoe Park, who was able to charge 1d per ton on all cargo entering the port, for upkeep of the lights. In 1836 Rebow's lease on the lights was purchased by Trinity House, but in 1863 they were declared redundant due to a change the position of the channel used by ships entering and leaving the port, caused by shifting sands.[12]

They were in turn replaced by the pair of cast iron lights at nearby Dovercourt; these too remain in situ, but were decommissioned (again due to shifting of the channel) in 1917.

Painting of Harwich lighthouse by John Constable c.1820.

Painting of Harwich lighthouse by John Constable c.1820. The Harwich Low Lighthouse of 1818

The Harwich Low Lighthouse of 1818 Dovercourt High Light (1863)

Dovercourt High Light (1863) Dovercourt Low Light (1863)

Dovercourt Low Light (1863)

Architecture

Despite, or perhaps because of, its small size Harwich is highly regarded in terms of architectural heritage, and the whole of the older part of the town, excluding Navyard Wharf, is a conservation area.[13]

The regular street plan with principal thoroughfares connected by numerous small alleys indicates the town’s medieval origins, although many buildings of this period are hidden behind 18th century facades.

The extant medieval structures are largely private homes. The house featured in the image of Kings Head St to the left is unique in the town and is an example of a sailmaker's house, thought to have been built circa 1600. Notable public buildings include the parish church of St. Nicholas (1821)[14] in a restrained Gothic style, with many original furnishings, including a somewhat altered organ in the west end gallery. There is also the Guildhall of 1769, the only Grade I listed building in Harwich.[15]

The Pier Hotel of 1860 and the building that was the Great Eastern Hotel of 1864 can both been seen on the quayside, both reflecting the town's new importance to travellers following the arrival of the railway line from Colchester in 1854. In 1923, The Great Eastern Hotel was closed[16] by the newly formed LNER, as the Great Eastern Railway had opened a new hotel with the same name at the new passenger port at Parkeston Quay, causing a decline in numbers. The hotel became the Harwich Town Hall, which included the Magistrates Court and, following changes in local government, was sold and divided into apartments.

Also of interest are the High Lighthouse (1818), the unusual Treadwheel Crane (late 17th century), the Old Custom Houses on West Street, a number of Victorian shopfronts and the Electric Palace Cinema (1911), one of the oldest purpose-built cinemas to survive complete with its ornamental frontage and original projection room still intact and operational.

There is little notable building from the later parts of the 20th century, but major recent additions include the lifeboat station and two new structures for Trinity House. The Trinity House office building, next door to the Old Custom Houses, was completed in 2005. All three additions are influenced by the high-tech style.

Notable inhabitants

Harwich was the home town of Christopher Jones, the master and quarter-owner of the Mayflower. The famous diarist Samuel Pepys was the Member of Parliament for Harwich. Christopher Newport, captain of the expedition that founded Jamestown, Virginia, also hailed from Harwich. Captain Charles Fryatt lived in Harwich, and his body was brought back from Belgium in 1919 and he was buried at Dovercourt. More recently, the reclusive but well-known award-winning Western Australian writer Randolph Stow made his home in Harwich, in the knowledge that his ancestors lived in the area. Stow's 1984 novel The Suburbs of Hell draws on Old Harwich for its setting. Stow was a notable and determined supporter of the project to conserve the historic character of the town.

Harwich has also historically hosted a number of notable visitors, including many members of British and European royalty; in many instances these visits are linked with Harwich's rich maritime past.[17]

Sport

Harwich is home to Harwich & Parkeston F.C.; Harwich and Dovercourt RFC; Harwich & Dovercourt Sailing Club; Harwich, Dovercourt & Parkeston Swimming Club; Harwich & Dovercourt Rugby Union Football Club; Harwich & Dovercourt Cricket Club; and Harwich Runners who with support from Harwich Swimming Club host the annual Harwich Triathlons.

See also

- Harwich Redoubt

- Harwich (UK Parliament constituency)

- Harwich and Dovercourt High School

- Harwich Lifeboat Station

- Harwich Mayflower Project

Notes

- ↑ "Town population 2011". Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ Trollope, C., "The Defences of Harwich", Fort (Fortress Study Group), 1982, (10), pp5-31

- ↑ Adrian Room, Placenames of the World (2003), "Harwich". Retrieved 20 December 2010

- ↑ "Charles Louis Schomberg, Marquess of Harwich". The Peerage. Lundy Consulting Ltd. 10 May 2003. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 Daniel Defoe, A tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-1726) Available online here

- ↑ "www.harwichanddovercourt.co.uk".

- ↑ 'Harwich for the Continent', LNER poster

- ↑ 'Harwich for the Continent ', LNER poster, 1934

- ↑ High Lighthouse, Harwich British Listed Buildings. Retrieved May 2nd, 2016

- ↑ Harwich High The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved May 2nd, 2016

- ↑ "Local newspaper report".

- ↑ "Harwich Society website".

- ↑ Harwich Society, 2008.

- ↑ UK Attraction: St. Nicholas Church.

- ↑ Harwich Society, 2008.

- ↑ Hughes, Geoffrey (1986). LNER. Shepperton: Ian Allan Ltd. p. 157. ISBN 0-7110-1428-0.

- ↑ "Vision of Britain". visionofbritain.org. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

References

- Pevsner, Nikolaus and Radcliffe, Enid (2002). The Buildings of England: Essex. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09601-1.

- Smith Stuart Reynolds (consultants); et al. (2006). Tendring District Council Conservation Area Review: Harwich Conservation Area (PDF). Tendring District Council.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harwich. |