Harlem riot of 1943

| Harlem riot of 1943 | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 1–2, 1943 |

| Location | Harlem, New York City |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 6 |

| Arrested | 600 |

On August 1 and 2 of 1943, a race riot took place in Harlem, New York City, after a white police officer, James Collins, shot and wounded Robert Bandy, an African American soldier who inquired about a woman's arrest for disorderly conduct and sought to have her released. Bandy reportedly hit the officer, and was shot while trying to flee from the scene. A crowd of about 3,000 people gathered around Bandy and the officer as they attempted to enter a hospital for treatment, when someone in the crowd incorrectly reported that Bandy had been killed. A riot ensued that lasted for two days and led to six deaths, nearly 600 arrests, vandalism, theft, property destruction and monetary damages. New York City Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia ultimately restored order in the borough on August 2 with the recruitment of several thousand officers and volunteer forces to contain the rioters.

The underlying causes of the riot stemmed from a disparity between the values of American democracy and the conditions of black citizens, strained and exemplified by World War II. Discriminatory practices in employment and city services created tension among African Americans as they sought to reject their state of living. Segregated in the Army, Bandy came to represent black soldiers, and Collins came to represent white suppression to Harlemites. Culturally, the riot inspired the "theatrical climax" of Ralph Ellison's novel Invisible Man, winner of the 1953 National Book Award, and artist William Johnson's representation of the "oppressed and debased community" in Moon Over Harlem.

Cause

On Sunday, August 1, 1943, a white policeman attempted to arrest an African American woman for disturbing the peace in the lobby of the Braddock Hotel. The hotel, which once hosted show business celebrities in the 1920s, had become a location known for prostitution by the 1940s. The Army designated the area as a "raided premise", and a policeman was stationed in the lobby to prevent further crime.[1]

Various accounts detail how Marjorie (Margie) Polite, the African American woman, became confrontational with James Collins, the white policeman. According to one, Polite checked into the hotel on August 1, but was unsatisfied and asked for another room. When she switched rooms and found the new accommodation did not have the shower and bath she wanted, Polite asked for a refund, which she received.[2] Afterwards, however, she asked for a $1 tip ($14 in 2014)[3] that she gave to an elevator operator to be returned. The operator refused; Polite began to protest loudly, which caught the attention of Collins. According to another account, she became drunk at a party in one of the rooms, and confronted the officer as she attempted to leave.[4]

After Collins told Polite to leave, she became verbally abusive of the officer and Collins arrested her on the grounds of disturbing the peace. Florine Roberts, the mother of Robert Bandy, a black soldier in the U.S. Army, observed the incident and asked for Polite's release. The official police report held that the soldier threatened Collins; in the report, Bandy and Mrs. Roberts proceeded to attack Collins.[2] Bandy then hit the officer, and while attempting to flee, Collins shot Bandy in the shoulder with his revolver.[2] In an interview with PM, the soldier stated that he intervened when the officer pushed Polite. According to Bandy, Collins threw his nightstick at Bandy, which he caught. When Bandy hesitated after Collins asked for its return, Collins shot him.[5] Bandy's wound was superficial, but he was taken to Sydenham Hospital for treatment. Crowds quickly gathered around Bandy as he entered the hospital, around the hotel, and around police headquarters, where a crowd of 3,000 amassed by 9:00 pm.[6][7] The crowds combined and grew tense as rumors that an African American soldier had been shot soon turned to rumors that an African American soldier had been killed.[6][7]

Riot

"The rumor is false that a Negro soldier was killed at the Braddock Hotel tonight. He is only slightly wounded and is in no danger. Go to your homes! [...] Don't destroy in one night the reputation as good citizens you have taken a lifetime to build. Go home – now!"

Message White spoke to rioters[8]

At 10:30 pm, the crowd became violent after an individual threw a bottle off of a roof into the crowd aggregated about the hospital. The group dispersed into gangs containing between 50–100 members. The gangs first broke windows of white businesses as they traveled through Harlem: if the mob was informed the business was under black ownership, it left the establishment alone. If the ownership was white, however, the store would be looted and vandalized.[7] Rioters broke streetlights and threw white mannequins onto the ground.[9] In grocery stores, the rioters took war-scarce items, such as coffee and sugar; clothing, liquor, and furniture stores were also looted.[7] Estimates put the total monetary damage between $250,000–$5,000,000, which included 1,485 stores burglarized and 4,495 windows broken.[10][11]

When Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia was informed of the situation at 9:00 pm, he met with police and visited the riot district with black authority figures such as Max Yergan and Hope Stevens.[12] La Guardia ordered all unoccupied officers into the region: in addition to the 6,000 city and military police, 1,500 volunteers were called on to help control the riot, with an additional 8,000 guardsmen "on standby".[13][14] Traffic was directed around Harlem to contain the riot.[12] After he returned from the tour, the mayor made the first of a series of radio announcements that urged Harlemites to return home. Soon after, he met with Walter Francis White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to discuss the appropriate action to take; White suggested that black leaders again visit the district to spread the message of order.[14] Just after 2:00 A.M, the mayor instructed all taverns to close.[12]

Aftermath

The riot ended on the night of August 2. Cleanup efforts started that day; the New York City Department of Sanitation worked to clean the area for three days and the New York City Departments of Buildings and Housing boarded windows. The city assigned a police escort for all department workers.[15] The Red Cross gave Harlemites lemonade and crullers, and the mayor organized various hospitals to handle an influx of patients.[16] By August 4, traffic had resumed through the borough, and taverns reopened the next day.[15] La Guardia had food delivered to the residents of Harlem, and on August 6, food supplies returned to normal levels.[17] Overall, six people died and nearly 700 were injured. Six hundred men and women were arrested in connection with the riot.[11]

Underlying issues

In a piece for the Berkeley Journal of Sociology, academic L. Alex Swan attributes the riot to a disparity between the values of American democracy and the conditions of black citizens.[18] Swan cites, for example, the segregation of blacks in the armed forces while the United States fought for freedom.[19] Charles Lawrence of Fisk University described "resentment of status given Negro members of the armed forces" as "perhaps the greatest single psychological factor in the making of the Harlem riot", as Bandy came to represent black soldiers and Collins came to represent white suppression.[20] When Franklin D. Roosevelt gave his Four Freedoms speech, calling for freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear for people "everywhere in the world", African Americans felt they never had such freedoms themselves, and were willing to fight for them domestically.[21] Michael Harrington described the black resident of Harlem as a "second-class citizen in his own neighborhood".[22]

After the Harlem Riot of 1935 caused widespread destruction, La Guardia ordered a commission to pinpoint its underlying causes: commission head E. Franklin Frazier wrote that "economic and social forces created a state of emotional tension which sought release upon the slightest provocation".[7] The report listed several "economic and social forces" that worked against blacks, including discrimination in employment and city services, overcrowding in housing, and police brutality. Specifically, it criticized New York City Police Commissioner Lewis Joseph Valentine and New York City Hospitals Commissioner Sigismund S. Goldwater, both of whom responded with criticisms of the report. Conflicted, La Guardia asked academic Alain LeRoy Locke to analyze both accounts and assess the situation: confidentially, he wrote to La Guardia that Valentine was blameworthy and listed several areas for immediate improvement, such as health and education. Publicly, he published an article in the Survey Graphic which blamed the 1935 riot on the state of affairs that La Guardia inherited.[23]

Communally, conditions for black Harlemites improved by 1943, with better employment in civil services, for instance, but economic problems became exacerbated under wartime conditions, which enforced employment discrimination in new war and non-war industries and business.[24][25] Though new projects such as the Harlem River Houses expanded black housing, by 1943, Harlem housing had deteriorated as new construction slowed and buildings were destroyed.[24][25] Although the state of African Americans improved relative to society, individuals could not accelerate their own progress.[26]

Cultural depictions

Several authors and artists have depicted the event in their respective publications and works. African American novelist James Baldwin wrote of the riot, which occurred on the same day as his father's funeral and his nineteenth birthday, in Notes of a Native Son.[27] "It seemed to me", Baldwin wrote, "that God himself had devised, to mark my father's end, the most sustained and brutally dissonant of codas".[28] In a commentary piece for The New York Times, Langston Hughes called the chapter "superb", and particularly quoted Baldwin's observation that "to smash something is the ghetto's chronic need".[29] Hughes himself wrote "The Ballad of Margie Polite", a poem on the riot published in New York Amsterdam News, which "seems to honor rather than censure Polite for her role as a catalyst" according to Laurie Leach of Studies in the Literary Imagination.[30] Ralph Ellison drew upon his experiences covering the riot for the New York Post as inspiration for the "theatrical climax" of Invisible Man, winner of the 1953 National Book Award.[31][32]

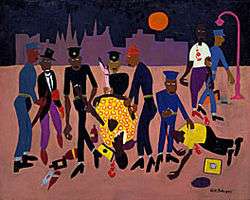

Artist William Johnson used images taken from news reports as inspiration for his c. 1943–1944 painting Moon Over Harlem: after "[stripping them] of their melodramatic quality", according to critic Richard Powell, Johnson "creates in their place a kind of expressive distortion and calculated rawness." Powell notes that the central figure in Moon Over Harlem, an upside-down African American woman harassed by three officers, represents "an oppressed and debased community, whose frustrations and self-destruction prompted an authoritative abuse of power".[33]

See also

- Beaumont Race Riot of 1943

- Detroit Race Riot (1943)

- Harlem Riot of 1964

- Mass racial violence in the United States

References

- ↑ Brandt 1996, p. 184

- 1 2 3 Capeci 1977, p. 100

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ Brandt 1996, p. 185

- ↑ Lawrence 1947, pp. 242–243

- 1 2 Capeci 1977, p. 101

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lawrence 1947, p. 243

- ↑ Brandt 1996, p. 194

- ↑ Brandt 1996, p. 188

- ↑ Capeci 1977, p. 102

- 1 2 Brandt 1996, p. 207

- 1 2 3 Capeci 1977, p. 103

- ↑ Brandt 1996, p. 190

- 1 2 Capeci 1977, p. 104

- 1 2 Brandt 1996, p. 206

- ↑ Capeci 1977, pp. 105–106

- ↑ Capeci 1977, p. 107

- ↑ Swan 1971, p. 77

- ↑ Swan 1971, p. 79

- ↑ Lawrence 1947, p. 244

- ↑ Swan 1971, p. 78

- ↑ Harrington, Michael (1997) [First published 1962]. The Other America: Poverty in the United States. Simon & Schuster. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-684-82678-3.

- ↑ Capeci 1977, pp. 5–7

- 1 2 Capeci 1977, p. 7

- 1 2 Lawrence 1947, pp. 243–244

- ↑ Swan 1971, p. 82

- ↑ Boyd, Herb (2009). Baldwin's Harlem: A Biography of James Baldwin. Simon and Schuster. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7432-9308-2.

- ↑ Baldwin, James (1984) [First published 1955]. Notes of a Native Son. Beacon Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8070-6431-3.

- ↑ Hughes, Langston (February 26, 1958). "Notes of a Native Son". The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- ↑ Leach, Laurie (September 22, 2007). "Margie Polite, the Riot Starter: Harlem, 1943". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 40 (2). (subscription required)

- ↑ Prescott, Orville (April 16, 1952). "Books of the Times". The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- ↑ Graham, Maryemma; Singh, Amritjit, eds. (1995). Conversations with Ralph Ellison. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-87805-781-1.

- ↑ Powell, Richard J. (1991). Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-8478-1421-3.

Bibliography

- Brandt, Nat (1996). Harlem at War: The Black Experience in WWII. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0462-4.

- Capeci, Dominic J. (1977). The Harlem Riot of 1943. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-0-87722-094-7.

- Lawrence, Charles R. Jr. "Race Riots in the United States 1942–1946". Fisk University. As published in Guzman, Jesse P. (1947). Negro Year Book: A Review of Events Affecting Negro Life, 1941–1946.

- Swan, L. Alex (1971). "The Harlem and Detroit Riots of 1943: A Comparative Analysis". Berkeley Journal of Sociology. Regents of the University of California. 16 (7): 75–93. JSTOR 40999915.