Gunpowder Empires

The Gunpowder Empires is a term used to describe the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires. Each of these three empires had considerable military success using the newly developed firearms, especially cannon and small arms, in the course of their empires.[1]

The Hodgson-McNeill concept

The phrase was coined by Marshall G.S. Hodgson and his colleague William H. McNeill at the University of Chicago. Hodgson used the phrase in the title of Book 5 ("The Second Flowering: The Empires of Gunpowder Times") of his highly influential three-volume work, The Venture of Islam (1974).[2] Hodgson saw gunpowder weapons as the key to the "military patronage states of the Later Middle Period" which replaced the unstable, geographically limited confederations of Turkic clans that prevailed in post-Mongol times. Hodgson defined a "military patronage state" as one having three characteristics:

first, a legitimization of independent dynastic law; second, the conception of the whole state as a single military force; third, the attempt to explain all economic and high cultural resources as appanages of the chief military families.[3]

Such states grew "out of Mongol notions of greatness," but "[s]uch notions could fully mature and create stable bureaucratic empires only after gunpowder weapons and their specialized technology attained a primary place in military life."[4]

McNeill argued that whenever such states “were able to monopolize the new artillery, central authorities were able to unite larger territories into new, or newly consolidated, empires.” [5] Monopolization was key. Although Europe pioneered the development of the new artillery in the fifteenth century, no state monopolized it. Gun-casting know-how had been concentrated in the Low Countries near the mouths of the Scheldt and Rhine rivers. France and the Habsburgs divided those territories among themselves resulting in an arms standoff.[6] By contrast, such monopolies allowed states to create militarized empires in the Near East, Russia and India, and “in a considerably modified fashion” in China and Japan.[7]

Recent views on the concept

More recently, the Hodgson-McNeill Gunpowder-Empire hypothesis has been called into disfavor as a neither "adequate [n]or accurate" explanation, although the term remains in use.[8] Reasons other than (or in addition to) military technology have been offered for the nearly simultaneous rise of three centralized military empires in contiguous areas dominated by decentralized Turkic tribes. One explanation, called "Confessionalization" by historians of fifteenth century Europe, invokes examination of how the relation of church and state "mediated through confessional statements and church ordinances" lead to the origins of absolutist polities. Douglas Streusand uses the Safavids as an example:

The Safavids from the beginning imposed a new religious identity on their general population; they did not seek to develop a national or linguistic identity, but their policy had that effect.[9]

One problem of the Hodgson-McNeill theory is that the acquisition of firearms does not seem to have preceded the initial acquisition of territory constituting the imperial critical mass of any of the three early modern Islamic empires. except in the case of the Mughal empire. Moreover, it seems that the commitment to military autocratic rule pre-dated the acquisition of gunpowder weapons in all three cases. Nor does it seem to be the case that the acquisition of gunpowder weapons and their integration into the military was influenced by considerations of whichever variety of Islam the particular empire promoted.[10] Whether or not gunpowder was inherently linked to the existence of any of these three empires, it cannot be questioned that each of the three acquired artillery and firearms early in their history and made such weapons an integral part of their military tactics.

Gunpowder weapons in the three empires

Ottoman Empire

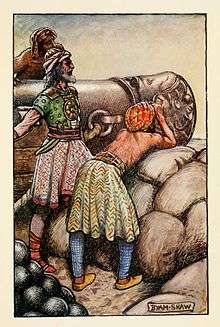

The first of the three empires to acquire gunpowder weapons was the Ottoman. Its decision was inevitable given that it faced Byzantine, Balkan and Hungarian fortresses and enemies already possessing such weapons. The adoption of the weapons by the Ottomans was so rapid that they "preceded both their European and Middle Eastern adversaries in establishing centralized and permanent troops specialized in the manufacturing and handling of firearms. "[11] But it was their use of artillery that shocked their adversaries and impelled the other two Islamic empires to accelerate their weapons program. The Ottomans had artillery at least by the reign of Bayazid I and used them in the sieges of Constantinople in 1399 and 1402. They finally proved their worth as siege engines in the successful siege of Salonica in 1430.[12] The Ottomans employed European founders to cast their cannons and by the siege of Constantinople in 1453, they had large enough cannons to batter the walls of the city to the surprise of the defenders. [13]

The Ottoman military's regularized use of firearms proceeded ahead of the pace of their European counterparts. The Janissaries had been an infantry bodyguard using bows and arrows. During the rule of Sultan Mehmed II they were drilled with firearms and became "perhaps the first standing infantry force equipped with firearms in the world."[12] The combination of artillery and Janissary firepower proved decisive at the Varna in 1444 against a force of Crusaders, the Başkent in 1473 against the Aq Qoyunlu,[14] and Mohács in 1526 against Hungary. But the battle which convinced the Safavids and the Mughals of the efficacy of gunpowder was Chaldiran.

At Chaldiran the Ottomans met the Safavids in battle for the first time. Sultan Selim I moved east with his field artillery in 1514 to confront what he perceived as a Shia threat instigated by Shah Ismail in favor of Selim's rivals. Ismail staked his reputation as a divinely-favored ruler on an open cavalry charge against a fixed Ottoman position. The Ottomans deployed their cannons between the carts that carried them, which also provided cover for the armed Janissaries. The result of the charge was devastating losses to the Safavid cavalry. The defeat was so thorough that the Ottoman forces were able to move on and briefly occupy the Safavid capital. Only the limited campaign radius of the Ottoman army prevented it from holding Tabriz and ending the Safavid rule.[15]

Safavid Empire

Although the Chaldiran defeat brought an end to Ismail's territorial expansion program, the shah nonetheless took immediate steps to protect against the real threat from the Ottoman sultanate by arming his troops with gunpowder weapons. Within two years of Chaldiran Ismail had a corps of musketeers (tofangchi) numbering 8,000 and by 1521 possibly 20,000.[16] After Abbas the Great reformed the army (around 1598), the Safavid forces had an artillery corp of 12,000 and 500 cannons as well as 12,000 musketeers.[17]

The Safavids first put their gunpowder arms to good use against the Uzbeks, who had invaded eastern Persia during the civil war that followed the death of Ismail I. The young shah Tahmasp I headed an army to relieve Herat and encountered the Uzbeks on September 24, 1528 at Jam, where the Safavids decisively beat the Uzbeks. The shah's army deployed cannons (swivel guns on wagons) in the center protected by wagons with cavalry on both flanks. Mughal emperor Babur described the formation at Jam as "in the Anatolian fashion."[18] The several thousand gun-bearing infantry also massed in the center as did the Janissaries of the Ottoman army. Although the Uzbek cavalry engaged and turned the Safavid army on both flanks, the Safavid center held (because not directly engaged by the Uzbeks). Rallying under Tahmasp's personal leadership the infantry of the center engaged and scattered the Uzbek center and secured the field.[19]

Mughal Empire

.jpg)

By the time he was invited by Lodi governor of Lahore Daulat Khan to support his rebellion against Lodi Sultan Ibrahim Khan, Babur was familiar with gunpowder firearms and field artillery and a method for deploying them. Babur had employed Ottoman expert Ustad Ali Quli, who showed Babur the standard Ottoman formation—artillery and firearm-equipped infantry protected by wagons in the center and the mounted archers on both wings. Babur used this formation at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, where the Afghan and Rajput forces loyal to the Delhi sultanate, though superior in numbers but without the gunpowder weapons, were defeated. The decisive victory of the Timurid forces is one reason opponents rarely met Mughal princes in pitched battle over the course of the empire's history.[20]

-

Mughal musketeer

References

- ↑ Charles T. Evans. "The Gunpowder Empires". Northern Virginia Community College. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ↑ Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974) ("Hodgson").

- ↑ Hodgson, 2:405-06.

- ↑ Hodgson, 3:16.

- ↑ William H. McNeill, “The Age of Gunpowder Empires, 1450-1800” in Islamic & European Expansion: The Forging of a Global Order edited by Michael Adas (pp. 103-139) (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993) (“McNeill”), p. 103.

- ↑ McNeill, pp. 110-11.

- ↑ McNeill, p. 103.

- ↑ Douglas E. Streusand, Islamic Gunpowder Empires: Otomans, Safavids, and Mughals (Philadelphia: Westview Press, c. 2011) ("Streusand"), p. 3.

- ↑ Streusand, p. 4.

- ↑ Gábor Ágoston, Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2005) ("Ágoston”), p. 192.

- ↑ Ágoston, p. 92.

- 1 2 Streusand, p. 83.

- ↑ McNeill, p. 125.

- ↑ Shai Har-El, Struggle for Domination in the Middle East: The Ottoman-Mamluk War, 1485-91 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995), pp. 98-99

- ↑ Streusand, p. 145.

- ↑ Mathee, Rudi (December 15, 1999). "Firearms". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved February 1, 2015. (Updated as of January 26, 2012.)

- ↑ Ágoston, pp. 59-60 & n.165.

- ↑ Alexander Mikaberidze, "Jam, Battle of (1528)" in Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia ed. Alexander Mikaberidze (Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, ©2011), vol i, pp. 442-43.

- ↑ Streusand, p. 170.

- ↑ Streusand, p. 255.