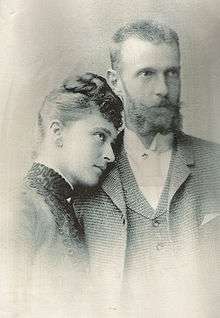

Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine (1864–1918)

Grand Duchess Elisabeth of Russia (Russian: Елизавета Фëдоровна Романова, Yelizaveta Fyodorovna Romanova; canonized as Holy Martyr Yelizaveta Fyodorovna; 1 November 1864 – 18 July 1918) was a German princess of the House of Hesse-Darmstadt, and the wife of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, fifth son of Emperor Alexander II of Russia and Princess Marie of Hesse and the Rhine. She was also a maternal great-aunt of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the consort of Elizabeth II.

Granddaughter of Queen Victoria and an older sister of Alexandra, the last Russian Empress, Elisabeth became famous in Russian society for her beauty and charitable works among the poor. After the Socialist Revolutionary Party's Combat Organization murdered her husband with a dynamite bomb in 1905, Elisabeth publicly forgave Sergei's murderer, Ivan Kalyayev, and campaigned without success for him to be pardoned. She then departed the Imperial Court and became a nun, founding the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent dedicated to helping the downtrodden of Moscow. In 1918 she was arrested and ultimately executed by the Bolsheviks.

In 1981 Elisabeth was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, and in 1992 by the Moscow Patriarchate.

Princess of Hesse

Elisabeth was born on 1 November 1864 as the second child of Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and British Princess Alice. Through her mother, she was a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. Princess Alice chose the name "Elisabeth" for her daughter after visiting the shrine of St. Elizabeth of Hungary, ancestress of the House of Hesse, in Marburg. Alice so admired St. Elisabeth that she decided to name her new daughter after her. Elisabeth was known as "Ella" within her family.[1]

Though she came from one of the oldest and noblest houses in Germany, Elisabeth and her family lived a rather modest life by royal standards. The children swept the floors and cleaned their own rooms, while their mother sewed dresses herself for the children. During the Austro-Prussian War, Princess Alice often took Elisabeth with her while visiting wounded soldiers in a nearby hospital. In this relatively happy and secure environment, Elisabeth grew up surrounded by English domestic habits, and English became her first language. Later in life, she would tell a friend that, within her family, she and her siblings spoke English to their mother and German to their father.

In the autumn of 1878, diphtheria swept through the Hesse household, killing Elisabeth's youngest sister, Marie on 16 November, as well as her mother Alice on 14 December. Elisabeth had been sent away to her paternal grandmother's home at the beginning of the outbreak and she was the only member of her family to remain unaffected. When she was finally allowed to return home, she described the meeting as "terribly sad" and said that everything was "like a horrible dream".

Admirers and suitors

Charming and with a very accommodating personality, Elisabeth was considered by many historians and contemporaries to be one of the most beautiful women in Europe at that time. As a young woman, she caught the eye of her elder cousin, the future German Emperor William II. He was a student then at Bonn University, and on weekends he often visited his Aunt Alice and his Hessian relatives. During these frequent visits, he fell in love with Elisabeth,[2] writing numerous love poems and regularly sending them to her. He proposed to Elisabeth in 1878.

Besides William II, she had many other admirers, among them Lord Charles Montagu, the second son of the 7th Duke of Manchester, and Henry Wilson, later a distinguished soldier.

Yet another of Elisabeth's suitors was the future Frederick II, Grand Duke of Baden, William's first cousin. Queen Victoria described him as "so good and steady", with "such a safe and happy position," that when Elisabeth declined to marry him the Queen "deeply regretted it". Frederick's grandmother, the Empress Augusta, was so furious at Elisabeth's rejection of Frederick that it took some time for her to forgive Elisabeth.

Other admirers included:

- Elisabeth's husband's cousin, Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (the poet KR). He wrote a poem about her first arrival in Russia, and the general impression she made to all the people present at the time.

- Prince Felix Yusupov considered her a second mother, and stated in his memoirs that she helped him greatly during the most difficult moments of his life.

- As a young girl, Queen Marie of Romania was very fascinated with her Cousin Ella, and would later describe her beauty and sweetness in her memoirs as "a thing of dreams".

- The French Ambassador to the Russian court, Maurice Paleologue, wrote in his memoirs how Elisabeth was capable of arousing what he described as "profane passions".

But it was a Russian Grand Duke who ultimately won Elisabeth's heart. Elisabeth's great-aunt, Empress Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, was a frequent visitor to Hesse. During these visits, she was usually accompanied by her youngest sons, Sergei and Paul. Elisabeth had known the boys since they were children, and she initially viewed them as haughty and reserved. Sergei, especially, was a very serious young man, intensely religious, and he found himself attracted to Elisabeth after seeing her as a young woman for the first time in several years.

At first, Sergei made little impression on Elisabeth. But after the death of both of Sergei’s parents within a year of each other and the shock of his loss caused Elisabeth to gradually see Sergei “in a new light”. She had felt this same grief after the death of her mother, and their other similarities (both were artistic and religious) began to draw them closer together. It was said that Sergei was especially attached to Elisabeth because she had the same character as his beloved mother. So when Sergei proposed to her for the second time, she accepted—much to the chagrin of her grandmother Queen Victoria.

Grand Duchess of Russia

Sergei and Elisabeth married on 15 (3) June 1884, at the Chapel of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. She became Grand Duchess Yelizaveta Fyodorovna. It was actually at the wedding that Sergei's 16-year-old nephew, Tsarevich Nicholas, first met his future wife, Elisabeth's youngest sister, Princess Alix.

The new Grand Duchess made a good first impression on her husband’s family and the Russian people. “Everyone fell in love with her from the moment she came to Russia from her beloved Darmstadt”, wrote one of Sergei's cousins. The couple settled in the Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace in St. Petersburg; after Sergei was appointed Governor-General of Moscow by his elder brother, Tsar Alexander III, in 1892, they resided in one of the Kremlin palaces. During the summer, they stayed at Ilyinskoe, an estate outside Moscow that Sergei had inherited from his mother.

The couple never had children of their own, but their Ilyinskoe estate was usually filled with parties that Elisabeth organized especially for children. They eventually became the foster parents of Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich and Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, Sergei’s niece and nephew.

Although Elisabeth was not legally required to convert to Russian Orthodoxy from her native Lutheran religion, she voluntarily chose to do so in 1891. Although some members of her family questioned her motives, her conversion appears to have been sincere.

Elisabeth was somewhat instrumental in the marriage of her nephew-by-marriage, Tsar Nicholas II, to her youngest sister Alix. Much to the dismay of Queen Victoria, Elisabeth had been encouraging Nicholas, then tsarevich, in his pursuit of Alix. When Nicholas did propose to Alix in 1894, and Alix rejected him on the basis of her refusal to convert to Orthodoxy, it was Elisabeth who spoke with Alix and encouraged her to convert. When Nicholas proposed to her again, a few days later, Alix then accepted.

On 18 February 1905, Sergei was assassinated in the Kremlin by the Socialist-Revolutionary, Ivan Kalyayev. The event came as a terrible shock to Elisabeth, although it was as if her prophecy had come true that "God will punish us severely" which she made after the Grand Duke expelled 20,000 Jews from Moscow, by simply surrounding thousands of families houses with soldiers and expelling the Jews without any notice overnight out of their homes and the city, but she never lost her calm. Her niece Marie later recalled that her aunt’s face was “pale and stricken rigid” and she would never forget her expression of infinite sadness. In her rooms, said Marie, Elisabeth “let herself fall weakly into an armchair...her eyes dry and with the same peculiar fixity of gaze, she looked straight into space, and said nothing.” As visitors came and went, she looked without ever seeming to see them. Throughout the day of her husband's murder, Elisabeth refused to cry. But Marie recalled how her aunt slowly abandoned her rigid self-control, finally breaking down into sobs. Many of her family and friends feared that she would suffer a nervous breakdown, but she quickly recovered her equanimity.

According to Edvard Radzinsky,

"Elizabeth spent all the days before the burial in ceaseless prayer. On her husband's tombstone she wrote: 'Father, release them, they know not what they do.' She understood the words of the Gospels heart and soul, and on the eve of the funeral she demanded to be taken to the prison where Kalyayev was being held. Brought into his cell, she asked, 'Why did you kill my husband?' 'I killed Sergei Alexandrovich because he was a weapon of tyranny. I was taking revenge for the people.' 'Do not listen to your pride. Repent... and I will beg the Sovereign to give you your life. I will ask him for you. I myself have already forgiven you.' On the eve of revolution, she had already found a way out; forgiveness! Forgive through the impossible pain and blood -- and thereby stop it then, at the beginning, this bloody wheel. By her example, poor Ella appealed to society, calling upon the people to live in Christian faith. 'No!" replied Kalyayev. 'I do not repent. I must die for my deed and I will... My death will be more useful to my cause than Sergei Alexandrovich's death.' Kalyayev was sentenced to death. 'I am pleased with your sentence,' he told the judges. 'I hope that you will carry it out just as openly and publicly as I carried out the sentence of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Learn to look the advancing revolution right in the face.'"[3]

Kalyayev was hanged on 23 May 1905.

Religious life

After Sergei’s death, Elisabeth wore mourning clothes and became a vegetarian. In 1909, she sold off her magnificent collection of jewels and sold her other luxurious possessions; even her wedding ring was not spared. With the proceeds she opened the Convent of Saints Martha and Mary and became its abbess.

She soon opened a hospital, a chapel, a pharmacy and an orphanage on its grounds. Elisabeth and her nuns worked tirelessly among the poor and the sick of Moscow. She often visited Moscow’s worst slums and did all she could to help alleviate the suffering of the poor.

For many years, Elisabeth's institution helped the poor and the orphans in Moscow by fostering the prayer and charity of devout women. Here, there arose a vision of a renewed diaconate for women, one that combined intercession and action in the heart of a disordered world. Although the Orthodox Church rejected her idea of a female diaconate, it did bless and encourage Elisabeth's many charitable efforts.

In 1916, Elisabeth had what was to be her final meeting with sister Alexandra, the tsarina, at Tsarskoye Selo. While the meeting took place in private, the tutor to the tsar's children apparently recalled that the discussion included Elisabeth expressing her concerns over the influence that Grigori Rasputin had over Alexandra and the imperial court, and begging her to heed the warnings of both herself and other members of the imperial family.

In 2010 an historian claimed that Elisabeth may have been aware that the murder of Rasputin was to take place and secondly, she knew who was going to commit that particular murder when she wrote a letter and sent it to the Tsar and two telegrams to Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and Zinaida Yusupova, her friend. The telegrams, which were written the night of the murder, reveal that the Grand Duchess was aware of who the murderers were before that information had been released to the public, and she stated that she felt that the killing was a "patriotic act."[4]

Murder

In 1918, Lenin ordered the Cheka to arrest Elisabeth. They then exiled her first to Perm, then to Yekaterinburg, where she spent a few days and was joined by others: the Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich Romanov; Princes Ioann Konstantinovich, Konstantin Konstantinovich, Igor Konstantinovich and Vladimir Pavlovich Paley; Grand Duke Sergei's secretary, Fyodor Remez; and Varvara Yakovleva, a sister from the Grand Duchess's convent. They were all taken to Alapayevsk on 20 May 1918, where they were housed in the Napolnaya School on the outskirts of the town.

At noon on 17 July, Cheka officer Pyotr Startsev and a few Bolshevik workers came to the school. They took from the prisoners whatever money they had left and announced that they would be transferred that night to the Upper Siniachikhensky factory compound. The Red Army guards were told to leave and Cheka men replaced them. That night the prisoners were awakened and driven in carts on a road leading to the village of Siniachikha, some 18 kilometres (11 miles) from Alapayevsk where there was an abandoned iron mine with a pit 20 metres (66 feet) deep. Here they halted. The Cheka beat all the prisoners before throwing their victims into this pit, Elisabeth being the first. Hand grenades were then hurled down the shaft, but only one victim, Fyodor Remez, died as a result of the grenades.

According to the personal account of Vasily Ryabov, one of the killers, Elisabeth and the others survived the initial fall into the mine, prompting Ryabov to toss in a grenade after them. Following the explosion, he claimed to have heard Elisabeth and the others singing an Orthodox hymn from the bottom of the shaft.[5] Unnerved, Ryabov threw down a second grenade, but the singing continued. Finally a large quantity of brushwood was shoved into the opening and set alight, upon which Ryabov posted a guard over the site and departed.

Early on 18 July 1918, the leader of the Alapayevsk Cheka, Abramov, and the head of the Yekaterinburg Regional Soviet, Beloborodov, who had been involved in the execution of the Imperial Family, exchanged a number of telegrams in a pre-arranged plan saying that the school had been attacked by an "unidentified gang". A month later, Alapayevsk fell to the White Army of Admiral Alexander Kolchak.

Legacy

| Saint and New Martyr, Elisabeth Romanov | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Saint, Princess and New Martyr | |

| Born | 1 November 1864 |

| Died | 18 July 1918 |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized |

1981 (ROCOR) 1992 (Moscow) by Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia and Moscow Patriarchate respectively |

On 8 October 1918, White Army soldiers discovered the remains of Elisabeth and her companions, still within the shaft where they had been murdered. Despite having lain there for almost three months, the bodies were in relatively good condition. Most were thought to have died slowly from injuries or starvation, rather than the subsequent fire. Elisabeth had died of wounds sustained in her fall into the mine, but before her death had still found strength to bandage the head of the dying Prince Ioann with her wimple. With the Red Army approaching, their remains were removed further east and buried in the cemetery of the Russian Orthodox Mission in Peking (now Beijing), China, before being ultimately taken to Jerusalem, where they were laid to rest in the Church of Maria Magdalene.

Elisabeth was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in 1981, and in 1992 by the Moscow Patriarchate as New Martyr Yelisaveta Fyodorovna. Her principal shrines are the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent she founded in Moscow, and the Saint Mary Magdalene Convent on the Mount of Olives, which she and her husband helped build, and where her relics (along with those of Nun Barbara, her former maid) are enshrined. She is one of the ten 20th-century martyrs from across the world who are depicted in statues above the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey, London, England,[6] and she is also represented in the restored nave screen installed at St Albans Cathedral in April 2015.[7]

A statue of Elisabeth was erected in the garden of her convent after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Its inscription reads: "To the Grand Duchess Yelizaveta Fyodorovna: With Repentance."

Rehabilitation

On 8 June 2009, the Prosecutor General of Russia officially posthumously rehabilitated Yelizaveta Fyodorovna, along with other Romanovs: Mikhail Alexandrovich, Sergei Mikhailovich, Ioann Konstantinovich, Konstantin Konstantinovich and Igor Konstantinovich. "All of these people were subjected to repression in the form of arrest, deportation and being held by the Cheka without charge," said a representative of the office.[8]

Titles and styles

- Her Grand Ducal Highness Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and the Rhine (1864–1884)

- Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Yelizaveta Fyodorovna of Russia (1884–1918)

- Holy Martyr Yelizaveta Fyodorovna (since 1981)

Ancestry

See also

Notes

- ↑ Carte de visite of the young princess http://www.jcosmas.com/cdvimages/cdv-26combined.jpg

- ↑ Packard, Jerrold M, Victoria's Daughters, New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1998. p. 176.

- ↑ Edvard Radzinsky, The Last Tsar, page 82.

- ↑ M. Nelipa (2010) The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin. A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire, p. 269-271.

- ↑ Serfes, Nektarios. "Murder of the Grand Duchess Elisabeth". The Lives of Saints. Archimandrite Nektarios Serfes.

- ↑ Burials and memorials in Westminster Abbey#20th Century Martyrs

- ↑ "New statues mark St Albans Cathedral's 900th anniversary". BBC Regional News, Beds, Herts & Bucks. 25 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ "Генпрокуратура решила реабилитировать казнённых членов царской семьи" [Prosecutor General's Office Decides to Rehabilitate the Executed Members of the Royal Family]. Nezavisimaya Gazeta (in Russian). 8 June 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

Further reading

- Paleologue, Maurice. An Ambassador's Memoirs, 1922

- Grand Duchess Marie of Russia. Education of a Princess, 1931

- Queen Marie of Romania. The Story of My Life, 1934

- Almedingen, E.M. An Unbroken Unity, 1964

- Duff, David. Hessian Tapestry, 1967

- Millar, Lubov, Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia, US edition, Redding, CA., 1991, ISBN 1-879066-01-7

- Mager, Hugo. Elizabeth, Grand Duchess of Russia, 1998, ISBN 0-7867-0509-4

- Zeepvat, Charlotte. Romanov Autumn, 2000, ISBN 5-8276-0034-2

- Belyakova, Zoia. The Romanovs: the Way It Was, 2000, ISBN 5-8276-0034-2

- Warwick, Christopher Ella: Princess, Saint and Martyr, 2007, ISBN 047087063X

- Croft, Christina Most Beautiful Princess — A Novel Based on the Life of Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia, 2008, ISBN 0-9559853-0-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Duchess Yelizaveta Fyodorovna. |

Orthodox sources

- The Life of the Holy Royal Martyr Grand Duchess Yelizaveta

- Life of the Holy New Martyr Grand Duchess Yelizaveta, by Metropolitan Anastassy

- Pilgrimage to Alapaevsk

- Photo Library of Saint Elizabeth

- OrthodoxWiki:Elizabeth the New Martyr

Orthodox hymns to Saint Elizabeth

- Akathist to the New Martyr Elizabeth

- Canon to the New Martyrs Grand Duchess Yelizaveta and Nun Barbara

Secular sources

- Murder details

- The Alexander Palace Time Machine

- American Reporter Interviews Elisabeth in 1917

- HIH Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna by Countess Alexandra Olsoufieff

- Yelizaveta and Romanov Discussion Forum

- Murder of the Romanovs at Alapayevsk