German submarine U-864

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | U-864 |

| Ordered: | 5 June 1941 |

| Builder: | DeSchiMAG AG Weser, Bremen |

| Yard number: | 1070 |

| Laid down: | 15 October 1942 |

| Launched: | 12 August 1943 |

| Commissioned: | 9 December 1943 |

| Fate: | Sunk with all hands, 9 February 1945 by HMS Venturer, North Sea west of Bergen |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Type IXD2 U-boat |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: |

|

| Beam: |

|

| Height: | 10.20 m (33 ft 6 in) |

| Draught: | 5.35 m (17 ft 7 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Range: |

|

| Test depth: | Calculated crush depth: 230 m (754 ft 7 in) |

| Boats & landing craft carried: | 2 dinghies |

| Complement: | 55–63 officers & ratings |

| Armament: |

|

| Service record | |

| Part of: |

|

| Commanders: |

|

| Operations: | 1 patrol: 7–9 February 1945 |

German submarine U-864 was a Type IX U-boat of Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine in World War II. She departed from Kiel on 5 December 1944 on her last mission, to transport to Japan a large quantity of mercury and parts and engineering drawings for German jet fighters. While returning to Bergen, Norway to repair a misfiring engine, U-864 was detected and sunk on 9 February 1945 by the British submarine HMS Venturer, killing all 73 on board. It is the only instance in the history of naval warfare where one submarine intentionally sank another while both were submerged.

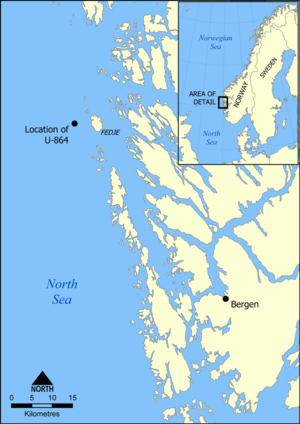

The shipwreck was located in March 2003 by the Royal Norwegian Navy 2 nmi (3.7 km; 2.3 mi) west of the island of Fedje in the North Sea, at 150 metres (490 ft).[1] The mercury had been seeping out of rusted containers, contaminating the region and sea life.[2] One study recommended entombing the wreck under a layer of sand as well as gravel and concrete. The Norwegian government instead awarded a contract to a salvage company to raise the wreck; however, the proposed operation was put on hold pending additional studies.

Design

German Type IXD2 submarines were considerably larger than the original Type IXs. U-864 had a displacement of 1,610 tonnes (1,580 long tons) when at the surface and 1,799 tonnes (1,771 long tons) while submerged.[3] The U-boat had a total length of 87.58 m (287 ft 4 in), a pressure hull length of 68.50 m (224 ft 9 in), a beam of 7.50 m (24 ft 7 in), a height of 10.20 m (33 ft 6 in), and a draught of 5.35 m (17 ft 7 in). The submarine was powered by two MAN M 9 V 40/46 supercharged four-stroke, nine-cylinder diesel engines plus two MWM RS34.5S six-cylinder four-stroke diesel engines for cruising, producing a total of 9,000 metric horsepower (6,620 kW; 8,880 shp) for use while surfaced, two Siemens-Schuckert 2 GU 345/34 double-acting electric motors producing a total of 1,000 shaft horsepower (1,010 PS; 750 kW) for use while submerged. She had two shafts and two 1.85 m (6 ft) propellers. The boat was capable of operating at depths of up to 200 metres (660 ft).[3]

The submarine had a maximum surface speed of 20.8 knots (38.5 km/h; 23.9 mph) and a maximum submerged speed of 6.9 knots (12.8 km/h; 7.9 mph).[3] When submerged, the boat could operate for 121 nautical miles (224 km; 139 mi) at 2 knots (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph); when surfaced, she could travel 12,750 nautical miles (23,610 km; 14,670 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). U-864 was fitted with six 53.3 cm (21 in) torpedo tubes (four fitted at the bow and two at the stern), 24 torpedoes, one 10.5 cm (4.13 in) SK C/32 naval gun, 150 rounds, and a 3.7 cm (1.5 in) with 2575 rounds as well as two 2 cm (0.79 in) anti-aircraft guns with 8100 rounds. The boat had a complement of fifty-five.[3]

Service history

Early career

Commanded throughout her entire career by Korvettenkapitän Ralf-Reimar Wolfram,[4] she served with the 4th U-boat Flotilla undergoing crew training from her commissioning until 31 October 1944. She was then reassigned to the 33rd U-boat Flotilla.[5]

Final voyage

According to decrypted intercepts of German naval communications with Japan, U-864's mission was to transport military equipment to Japan destined for the Japanese military industry, a mission code-named Operation Caesar. The cargo included approximately 67 short tons (61 t) of metallic mercury in 1,857 32-kilogram (71 lb) steel flasks stored in her keel. That the mercury was contained in steel canisters was confirmed when one of the canisters containing mercury was located and brought to the surface during surveys of her wreck in 2005. Approximately 1,500 short tons (1,400 t) of mercury was purchased by the Japanese from Italy between 1942 and Italy's surrender in September 1943. This had the highest priority for submarine shipment to Japan and was used in the manufacture of explosives, especially primers.

There was some speculation as to whether U-864 was carrying uranium oxide, as was U-234, which surrendered to the US Navy in the Atlantic on 15 May 1945, but Det Norske Veritas (DNV) concluded that there was no evidence that uranium oxide was on board U-864 when she departed Bergen. During the Norwegian Coastal Administration's investigation of the wreck of U-864 in 2005, radiation measurements were made but no traces of uranium oxide were found.[6]

According to her cargo list, U-864 also carried parts and engineering drawings for German jet fighter aircraft and other military supplies for Japan, while among her passengers were Messerschmitt engineers Rolf von Chlingensperg and Riclef Schomerus, Japanese torpedo expert Tadao Yamoto, and Japanese fuel expert Toshio Nakai.[6]

U-864, commanded by Wolfram, left Kiel on 5 December 1944, arriving at Horten Naval Base, Norway four days later. Before leaving Germany, U-864 had been refitted with a snorkel mast. Several messages found in the Ultra archives show that there were problems with the snorkel, which needed repairs before U-864 put to sea for her voyage to Japan. All Schnorkel trials and training were conducted at Horten near Oslo. U-864 would have needed to be certified ready to sail at Horten before proceeding to Bergen.[6]

While en route to Bergen, U-864 ran aground and had to stop in Farsund for repairs, not arriving in Bergen until 5 January 1945. While docked in the Bruno U-boat pens, U-864 received minor damage on 12 January when the pens and shipping in the harbour were attacked by 32 Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers and one Mosquito bomber of Numbers 9 and 617 Squadrons. At least one Tallboy bomb penetrated the roof of the bunker causing severe damage inside, and left one of the seven pens unusable for the remainder of the war.[7][8]

Sinking

Meanwhile, repairs and adjustments to her snorkel had been completed, and U-864 had commenced submerged trials. British submarine HMS Venturer, commanded by Lieutenant James "Jimmy" S. Launders, was sent on her eleventh patrol from the British submarine base at Lerwick in the Shetland Islands to Fedje, north of Bergen. After German radio transmissions regarding U-864 were decrypted, she was rerouted to intercept the U-boat. On 6 February U-864 passed the Fedje area without being detected, but one of her engines began to misfire and she was ordered to return to Bergen. A signal stated that a new escort would be provided her at Hellisøy on 10 February. She made for there, but on 9 February Venturer heard U-864's engine noise (Launders had decided not to use ASDIC since it would betray his position) and spotted the U-boat's periscope.

In an unusually long engagement for a submarine and in a situation for which neither crew had been trained, Launders waited 45 minutes after first contact before going to action stations, waiting in vain for U-864 to surface and thus present an easier target. Upon realizing they were being followed by the British submarine and that their escort had still not arrived, U-864 initiated zig-zagging evasive manoeuvres. Each submarine risked raising her periscope. Venturer had only eight torpedoes (four tubes and four reloads) as opposed to U-864's total of 22. After three hours, Launders decided to fire a spread of torpedoes at the U-boat's predicted position. The torpedoes were released beginning at 12:12 and then at 17 second intervals after that (taking four minutes to reach their target), and Launders then dived suddenly to evade any retaliation from his opponent. U-864 heard the torpedoes coming and also dived deeper and turned away to avoid them, managing to avoid the first three but unknowingly steering into the path of the fourth. Imploding, she split in two, sinking with all hands and coming to rest more than 150 m (500 ft) below the surface on the sea floor, 2 nmi (3.7 km; 2.3 mi) west of the island of Fedje.[6]

Rediscovery

In March 2003, the Royal Norwegian Navy minesweeper KNM Tyr, alerted by local fishermen, found the wreck.[9] An expedition to gather more detail by sonar mapping of the seafloor was mounted in October 2003.[10] The wreck was in two major sections, fore and aft, with the center section missing, including the conning tower. Further analysis was performed with a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) in August 2005, locating an additional 107 pieces of vessel debris in the area, likely parts of the exploded center section.[10] The mercury, contained in 1,857 rusting steel bottles located down in the vessel's keel, was found to be leaking out and currently poses a severe environmental threat, from potential mercury poisoning.[2]

So far 4 kilograms (8.8 lb) per year of mercury is leaking out into the surrounding environment, resulting in high levels of contamination in cod, torsk and edible crab around the wreck.[11] Boating and fishing near the wreck has been prohibited. Although attempts using robotic vehicles to dig into the half-buried keel were abandoned after the unstable wreck shifted, one of the steel bottles was recovered. Its original 5 millimetres (0.20 in) thick wall was found to have corroded badly, leaving in places a 1 millimetre (0.039 in) thickness of steel.[12]

The delicate condition of the 2,400-ton wreck, the rusting mercury bottles, and the live torpedoes on board would make a lifting operation extremely dangerous, with significant potential for an environmental catastrophe.[12][13] A three-year study by the Norwegian Coastal Administration has recommended entombing the wreck in a 12 metres (39 ft) thickness of sand, with a reinforcing layer of gravel or concrete to prevent erosion. This is being proposed as a permanent solution to the problem, and the proposal notes that similar techniques have been successfully used around 30 times to contain mercury-contaminated sites over the past 20 years.[14]

The proposal of entombing the wreck rather than removing it has been criticised by locals concerned about possible future leakage.[15]

On 11 November 2008, the Norwegian Coastal Administration awarded the contract for the possible salvage of U-864 submarine and its cargo of mercury to salvage company Mammoet Salvage BV. Mammoet, which was awarded the contract for the salvage of Russian nuclear submarine Kursk in 2001 had proposed a method of raising U-864's wreck which would satisfy the environmental requirements, described as "a safe and innovative salvage solution". This was reported to be a safe, fully remotely controlled operation which would raise the submarine and remove the source of pollution without the need for anyone working under water. On 29 January 2009, the Norwegian government approved the proposed method of raising the wreck, and the operation was scheduled to begin in 2010.[16][17] The operation was estimated to cost 1 billion kroner (USD 153 million).[18] However, the operation was postponed after the government wanted additional studies done.[19]

References

- ↑ "U-864: Extended investigations 2006". Norwegian Coastal Administration press release. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- 1 2 Olsvik, PA; Brattås, M; Lie, KK; Goksøyr, A. (April 2011). "Transcriptional responses in juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) after exposure to mercury-contaminated sediments obtained near the wreck of the German WW2 submarine U-864, and from Bergen Harbor, Western Norway". Chemosphere. 83 (4): 552–63. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.12.019. PMID 21195448.

- 1 2 3 4 Gröner 1991, pp. 74-75.

- ↑ "U864". U864 Homepage. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- ↑ "U-864". Uboat.net. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 "Salvage of U864 – Supplementary Studies – Study No. 7: Cargo" (PDF). Det Norske Veritas Report No. 23916. Det Norske Veritas. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009.

- ↑ "Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary, Campaign Diary, January 1945". Royal Air Force, UK Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 26 January 2007.

- ↑ "The Bases in Norway, Bergen". U-boat.net. Retrieved 26 January 2007.

- ↑ "U-864: Extended investigations 2006". Norwegian Coastal Administration. 2006. Archived from the original on 18 August 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Vurdering og anbefaling av videre miljøtiltak ved vraket av U-864" (PDF). Recommendation for further action, U-864 phase 1 (in Norwegian). Norwegian Coastal Administration. 20 January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2011. (Translation: Assessment and recommendation of further environmental initiatives by the wreck of U-864.)

- ↑ "NCA recommends covering wrecked mercury-submarine outside Bergen". Friends of the Earth Norway. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- 1 2 Martin Fletcher (19 December 2006). "Toxic timebomb surfaces 60 years after U-boat lost duel to the death". The Times. London. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ↑ Doug Mellgren (20 December 2006). "Sub Poses Environmental Threat in Norway". Associated Press report on Washington Post website.

- ↑ "The Norwegian Coastal Administration recommends encasing and covering the wreck of the submarine U-864" (PDF). Norwegian Coastal Administration press release. 19 December 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ↑ Alan Cowell and Walter Gibbs (11 January 2007). "Nazi U-Boat Imperils Norwegians Decades After the War". New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ "U-864 skal heves". Aftenposten. Bergens Tidende. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "Sunken WW2 submarine to be raised". The Norway Post. Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 30 January 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "Norway to raise toxic Nazi submarine wreck". The Local\. AFP. 30 January 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ↑ "U-864: Salvage operation postponed". Global Adventures, LLC. 15 March 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

Bibliography

- Busch, Rainer; Röll, Hans-Joachim (1999). German U-boat commanders of World War II : a biographical dictionary. Translated by Brooks, Geoffrey. London, Annapolis, Md: Greenhill Books, Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-186-6.

- Busch, Rainer; Röll, Hans-Joachim (1999). Deutsche U-Boot-Verluste von September 1939 bis Mai 1945 [German U-boat losses from September 1939 to May 1945]. Der U-Boot-Krieg (in German). IV. Hamburg, Berlin, Bonn: Mittler. ISBN 3-8132-0514-2.

- Gröner, Erich; Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin (1991). U-boats and Mine Warfare Vessels. German Warships 1815–1945. 2. Translated by Thomas, Keith; Magowan, Rachel. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-593-4.

- Preisler, Jerome; Sewell, Kenneth (2012). Code Name Caesar: The Secret Hunt for U-Boat 864 During World War II. Berkley Hardcover. ISBN 042524525X.

External links

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "The Type IXD2 boat U-864". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Roll of Remembrance

Coordinates: 60°46′10″N 4°37′15″E / 60.76944°N 4.62083°E