Franz Aepinus

| Franz Aepinus | |

|---|---|

| Born |

December 13, 1724 Rostock, Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

| Died | August 10, 1802 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | German, Russian |

| Fields | electricity and magnetism, astronomy |

Franz Ulrich Theodor Aepinus (December 13, 1724 – August 10, 1802) was a German and Russian Empire natural philosopher. Aepinus is best known for his researches, theoretical and experimental, in electricity and magnetism.

Life

He was born at Rostock in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. He was descended from Johannes Aepinus (1499–1553), the first to adopt the Greek form (αἰπεινός) of the family name Hugk or Huck, and a leading theologian and controversialist at the time of the Protestant Reformation. After studying medicine for a time, Franz Aepinus devoted himself to the physical and mathematical sciences, in which he soon gained such distinction that he was admitted a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. In 1755 he was briefly the director of the Astronomisches Rechen-Institut. In 1757 he settled in St Petersburg as member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and professor of physics, and remained there till his retirement in 1798. The rest of his life was spent at Dorpat.[1]

He enjoyed the favor of Empress Catherine II of Russia, who appointed him tutor to her son Paul, and endeavoured, without success, to establish normal schools throughout the empire under his direction.[1] In 1761, Aepinus was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1764, he was appointed as a head of the cryptographic service of Russia, and held this position till 1797, during 33 years.

Works

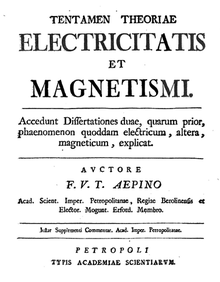

His principal work, Tentamen Theoriae Electricitatis et Magnetismi (An Attempt at a Theory of Electricity and Magnetism), published at St Petersburg in 1759, was the first systematic attempt to apply mathematical reasoning to these subjects. He also published a treatise, in 1761, De Distributione Caloris per Tellurem (On the Distribution of Heat in the Earth), and he was the author of memoirs on different subjects in astronomy, mechanics, optics and pure mathematics, contained in the journals of the learned societies of St Petersburg and Berlin. His discussion of the effects of parallax in the transit of a planet over the sun's disc excited great interest, having appeared (in 1764) between the dates of the two transits of Venus that took place in the 18th century.[1]

Electrical theories

Aepinus and Henry Cavendish devised theories of electricity which were essentially the same, yet had been framed without any communication between these two philosophers. Aepinus however published his theory about ten years before that of Cavendish. These are essentially modern theories which eventually put to rest the idea of two fluids.

Their theories said that

- ... the electric fluid is a substance, the particles of which repel each other, and attract the particles of all other matter, with a force inversely as the square of distance. [the square law was added later]

- The particles of all other matter also repel each other, and attract those of the electric fluid with a force varying according to the same law. Or, if we consider the electric fluid as matter different from all other matter, the particles of all matter, both those of the electric fluid, and of other matter, repel particles of the same kind, and attract those of a contrary kind, with a force inversely as the square of the distance.

Cavendish and Aepinus believed that the electric fluid was

- another sort of matter. ... Its weight in any body probably bears a very small proportion to the weight of the matter in the body, but yet the force with which the electric fluid in any body attracts any particle of matter in that body, must be equal to the force with which the matter of the body repels that particle, otherwise the body would appear electrical, as will afterwards appear.

In effect, they are imagining the 'electric fluid' as consisting of electrons with almost no mass, but still with substantial electrical attractive and repulsive power. Static electricity then becomes a matter of a superabundance of electrons in one body, and a shortage of electrons in another.

Notes

- 1 2 3

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aepinus, Franz Ulrich Theodor". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 258.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aepinus, Franz Ulrich Theodor". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 258.

References

- Electricity entry in Edinburgh Encyclopaedia of 1832

Further reading

- Heilbron, John L. (1970). "Aepinus, Franz Ulrich Theodosius". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 66–68. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

- Essay on the Theory of Electricity and Magnetism by Roderick Weir Home.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Franz Aepinus. |

- Weisstein, Eric W. (ed.). "Aepinus, Franz (1724–1802)". ScienceWorld.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Franz Aepinus", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.