Filipino mestizo

|

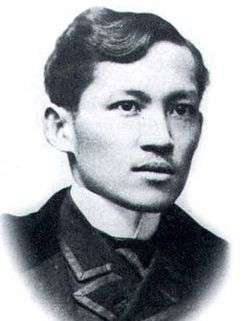

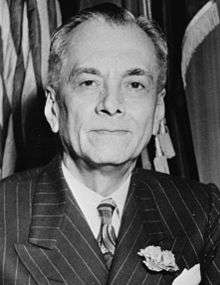

Notable Filipino mestizos: José Rizal • Andrés Bonifacio • Manuel L. Quezon • Datu Piang • Charlene Gonzales • Marian Rivera • Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala • Venus Raj • Vanessa Hudgens • Jaime Sin • Megan Young • Pia Wurtzbach | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Est. 30% - 35% of the population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Philippines, United States, Canada, Spain | |

| Languages | |

| Philippine languages, Spanish, English, other European languages, Japanese, Chinese, or other languages. | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Predominantly Roman Catholic, with a minority of Protestants) and Islam, or other religions. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Filipino people and foreign ethnic groups of his/her own ancestry |

| Demographics of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Filipinos |

| Mestizos |

| Immigrants or Expatriates |

Filipino mestizo is a term used in the Philippines to describe people of mixed Filipino and any foreign ancestry.[1] The word mestizo is of Spanish origin, and was originally used in the Americas to only describe people of mixed European and Native American ancestry.[2]

History

Spanish period

The Spanish expedition in 1565, prompted a period of Spanish colonization over the Philippines which lasted for 333 years. The Roman Catholic Church played an important role in allowing Spanish settlements in the Philippines. The Spanish government and religious missionaries were quick to learn native Filipino languages and Roman Catholic rituals were interpreted in accordance with Filipino beliefs and values. As a result, a folk Roman Catholicism developed in the Philippines.[3] European settlers from Spain and Mexico immigrated and their offspring (of either Spanish, or Spanish and Filipino) may have adopted the culture of their parents and grandparents. Most Filipinos of Spanish descent in the Philippines are of mixed ancestries or are of pure European ancestry. Some individuals still speak Spanish in the country, in addition, Chavacano (a creole language based largely on the Spanish vocabulary) is widely spoken in the Southern Philippines, including the Zamboanga Peninsula and its neighbouring regions. Spanish era periodicals record that as much as one third of the inhabitants of the island of Luzon possess varying degrees of Spanish and Latino admixture.[4] In addition to Luzon, select cities such as Bacolod, Cebu, Iloilo or Zamboanga which are home to historical military fortifications or commercial ports during the Spanish era also holds sizable mestizo communities.[5] This historical Spanish and Latino admixture is confirmed by a June 2015 genetic study done by the University of California's Institute of Genetics with a sample of 1700 Filipinos, that observed that "Among individuals reporting only an East Asian nationality, the large majority have only East Asian genetic ancestry; however, there are also individuals that appear to have mixed East Asian–European genetic ancestry that self-reported only their East Asian nationality. Of particular interest is the continuous nature of a modest amount of European genetic ancestry in self-identified Filipinos, consistent with older European admixture."[6]

Chinese immigration

Even before Spanish arrived in the Philippines, the Chinese have traded with the natives of the Philippines. During the colonial period, there was an increase in the number of Chinese immigrants into the Philippines. The Spaniards restricted the activities of the Chinese and confined them to the Parián which was located near Intramuros. Most of the Chinese residents earned their livelihood as traders.

Many of the Chinese who arrived during the Spanish period were Cantonese, who worked as labourers, but there were also Fujianese, who entered the retail trade. The Chinese resident in the islands were encouraged to intermarry with Filipinos, convert to Roman Catholicism and adopt Hispanic names, surnames and customs through the Catálogo alfabético de apellidos introduced by the Spaniards in the mid-19th century.

During the United States colonial period, the Chinese Exclusion Act of the United States was also applied to the Philippines.[7]

After the Second World War and the victory of the Communists in the Chinese Civil War, many refugees who fled from Mainland China settled in the Philippines. This group formed the bulk of the current population of Chinese Filipinos.[8] After the Philippines achieved full sovereignty on 4 July 1946, Chinese immigrants became naturalised Filipino citizens, while the children of these new citizens who were born in the country acquired Filipino citizenship from birth.[9]

Chinese Filipinos are one of the largest overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.[10] Sangleys—Filipinos with at least some Chinese ancestry—comprise 18-27% of the Philippine population.[11] There are roughly 1.5 million Filipinos with pure Chinese ancestry, or about 1.6% of the population.[12]

Colonial caste system

The history of racial mixture in the Philippines occurred on a smaller scale than other Spanish territories during the Spanish colonial period from the 16th to the 19th century. This ethno-religious social stratification schema was similar to the casta system used in Hispanic America, with some major differences.

The system was used for taxation purposes, with indios and negritos who lived within the colony paying a base tax, mestizos de sangley paying double the base tax, sangleys paying quadruple; blancos, however, paid no tax. The caste system was abolished after the Philippine Declaration of Independence from Spain in 1898, and the term Filipino was expanded to include the entire population of the Philippines regardless of racial ancestry. However, aspects of this class system persist to a certain degree in modern Philippines and are coloured by social and economic factors.

| Term | Definition | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Negrito | person of pure Aeta ancestry | |

| Indio | person of pure Austronesian ancestry | |

| Sangley | person of pure Chinese ancestry | |

| Mestizo de Sangley | person of mixed Chinese and Austronesian ancestry | |

| Árabe | person of pure Arab ancestry | |

| Mestizo de Bombay | person of mixed Indian and Austronesian ancestry | |

| Mestizo de Árabe | person of mixed Arab, Spanish, and Austronesian ancestry | |

| Mestizo de Español | person of mixed Spanish and Austronesian ancestry | |

| Mestizo de Judios | person of mixed Jew and Austronesian ancestry | |

| Tornatrás | person of mixed Spanish, Austronesian and Chinese ancestry | |

| Filipino/Insulares | person of pure Spanish descent born in the Philippines | |

| Americano | person of Criollo (either pure Spanish blood, or mostly), Castizo (1/4 Native American, 3/4 Spanish) or Mestizo (1/2 Spanish, 1/2 Native American) descent born in Spanish America ("from the Americas") | |

| Peninsulares | person of pure Spanish descent born in Spain ("from the Iberian Peninsula") |

Persons classified as blancos (whites) were subdivided into the peninsulares (persons of pure Spanish descent born in Spain); insulares or filipinos (persons of pure Spanish descent born in the Philippines); mestizos de español (persons of mixed Autronesian and Spanish ancestry), and tornatrás (persons of mixed Austronesian, Chinese, and Spanish ancestry). Manila and its arrabales was racially segregated, with blancos living in the walled city of Intramuros, unbaptised sangleys in the Paríán, Catholic sangleys and mestizos de sangley in Binondo, and anything beyond were reserved for indios with the exception of lands in Cebu and several other Spanish posts. Only mestizos de sangley were allowed to enter Intramuros to work as servants for blancos (including mestizos de español) and in various occupations needed for the colony.

Persons of pure Spanish descent living in the Philippines who were born in Hispanic America were classified as américanos. Mestizos and mulattoes born in Hispanic America living in the Philippines kept their legal classification as such, and usually came as indentured servants to the américanos. The Philippine-born children of américanos were classified as filipinos. Philippine-born children of mestizos and mulattoes from Hispanic America were classified based on patrilineal descent.

The indigenous peoples of the Philippines were referred to as Indios (for those of pure Austronesian descent) and negritos. Indio was a general term applied to native Austronesians as a legal classification; it was only applied to Christianised natives who lived in proximity to the Spanish colonies. Persons who lived outside of Manila, Cebu, and areas with a large Spanish concentration were classified as such: naturales were baptised Austronesians of the lowland and coastal towns. Unbaptised Austronesians and Aetas who lived in the towns were classified as salvajes (savages) or infieles (infidels). Remontados ("those who went to the mountains") and tulisanes (bandits) were Austronesians and Aetas who refused to live in towns and moved upland. These were considered to live outside the social order as Catholicism was a driving force in everyday life, as well as determinant of social class.

The Spanish legally classified the Aetas as negritos based on their appearance. The word term would be misinterpreted and used by future European scholars as an ethnoracial term in and of itself. Both Christianised Aetas who lived in the colony and unbaptised Aetas who lived in tribes outside of the colony were classified negrito. Christianised Aetas who lived in Manila were not allowed to enter Intramuros and lived in areas designated for indios. Persons of Aeta descent were also viewed as being outside the social order as they usually lived in tribes beyond settlements and resisted conversion to Christianity.

Marriages

This legal system of racial classification based on patrilineal descent had no parallel anywhere in the Spanish-ruled colonies in the Americas. In general, a son born of a sangley male and an indio or mestiza de sangley was classified as mestizo de sangley; all subsequent male descendants were mestizos de sangley regardless of whether they married an india or a mestiza de sangley. A daughter born in such a manner, however, acquired the legal classification of her husband, i.e., she became an india if she married an indio but remained a mestiza de sangley if she married a mestizo de sangley or a sangley. In this way, a chino mestizo male descendant of a paternal sangley ancestor never lost his legal status as a mestizo de sangley no matter how little percentage of Chinese blood he had in his veins or how many generations had passed since his first Chinese ancestor; he was thus a mestizo de sangley in perpetuity.

However, a mestiza de sangley who married a blanco (Filipino, mestizo de español, peninsular, or américano) kept her status, but her children were classified as tornatrás. An india who married a blanco also kept her status, while her children were classified as mestizo de español. A mestiza de español who married another blanco would maintain her caste, but was considered an india if she married an indio, thus forcing her to pay the indio tax rate. She would, however, remain in her caste if she married a mestizo de español, filipino, or peninsular.

Conversely, a mestizo de español or sangley kept his status regardless of whom he married. If a mestizo de español or sangley married a filipina (i.e., Philippine-born woman of pure Spanish descent), the woman would lose her status and be classified with her husband, becoming a mestiza de español or sangley. If a filipina married an indio, her legal status would change to india despite being of pure Spanish descent.

Persons of mixed Aeta and Austronesian ancestry were classified based on patrilineal descent. If the father was negrito and the mother was India (Austronesian), the child was classified as negrito. If the father was indio and the mother was negrita, the child was classified as indio.

See also

- Template:Miscegenation in Spanish Philippines

- Demographics of the Philippines

- Ethnic groups in the Philippines

- Comparisons with other countries

- Casta (comparable caste system in Latin America)

- Indo people of Indonesia

- Eurasian

- Amerasian

- Afro-Asian

- Multiracial

- Template:Miscegenation in Spanish colonies

References

- ↑ "Mestizo - Define Mestizo at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ "Mestizo - Define Mestizo at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ International Studies & Programs at Michigan State University. "Asian Studies Center - Michigan State University - Oops!". msu.edu.

- ↑ Jagor, Fëdor, et al. (1870). The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes

- ↑ Quinze Ans de Voyage Autor de Monde Vol. II ( 1840). Retrieved 2014-7-25 from Institute for Research of Iloilo Official Website.

- ↑ *Institute for Human Genetics, University of California San Francisco (2015). "Self-identified East Asian nationalities correlated with genetic clustering, consistent with extensive endogamy. Individuals of mixed East Asian-European genetic ancestry were easily identified; we also observed a modest amount of European genetic ancestry in individuals self-identified as Filipinos" (PDF). Genetics Online: 1.

- ↑ "Chinese Exclusion Act: 1882". thenagain.info.

- ↑ http://filipino-chinese.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2&Itemid=1

- ↑ "Website Disabled". homestead.com.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Sangley, Intsik und Sino : die chinesische Haendlerminoritaet in den Philippine".

- ↑ "The ethnic Chinese variable in domestic and foreign policies in Malaysia and Indonesia" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-23.

Further reading

- Wickberg, Edgar. (March 1964) "The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine History". The Journal of Southeast Asian History, 5(1), 62–100. Lawrence, Kansas: The University of Kansas, CEAS.

- Monroy, Emily. (23 August 2002) "Race Mixing and Westernization in Latin America and the Philippines". analitica.com. Caracas, Venezuela.

- Gambe, Annabelle R. (2000) Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. Münster, Hamburg and Berlin: LIT Verlag.

- Anderson, Benedict. (1988) Cacique Democracy in the Philippines: Origins and Dreams.

- Weightman, George H. (February 1960) The Philippine Chinese: A Cultural History of A Marginal Trading Company. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Dissertation Information Service.

- Tettoni, Luca Invernizzi and Sosrowardoyo, Tara. (1997). Filipino Style. Periplus Editions Ltd. Hong Kong, China.

- Tan, Hock Beng. (1994). Tropical Architecture and Interiors. Page One Publishing Pte Ltd. Singapore.

- Advisory Body Evaluation (1999). UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Medina, Elizabeth. (1999) "Thru the Lens of Latin America: A Wide-Angle View of the Philippine Colonial Experience". Santiago, Chile.

- The Colonial Imaginary. Photography in the Philippines during the Spanish Period 1860–1898 (2006). Casa Asia: Centro Cultural Conde Duque. Madrid, Spain.

- Blair, E. H. and Robertson, J.A. (editors). (1907) History of the Philippine Islands Vols. 1 and 2 by Dr. Antonio de Morga (Translated and Annotated in English). The Arthur H. Clark Company. Cleveland, Ohio.

- Craig, Austin. (2004). Lineage, Life and Labors of Jose Rizal, Philippine Patriot. Kessinger Publishing. Whitefish, Montana.

- Culture and fertility: the case of the Philippines

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)