Ethanol precipitation

Ethanol precipitation is a method used to purify and/or concentrate RNA, DNA, and polysaccharides such as pectin and xyloglucan from aqueous solutions by adding ethanol as an antisolvent.

DNA Precipitation

Theory

DNA is polar due to its highly charged phosphate backbone. Its polarity makes it water-soluble (water is polar) according to the principle "like dissolves like".

Because of the high polarity of water, illustrated by its high dielectric constant of 80.1 (at 20 °C), electrostatic forces between charged particles are considerably lower in aqueous solution than they are in a vacuum or in air.

This relation is reflected in Coulomb's law, which can be used to calculate the force acting on two charges and separated by a distance by using the dielectric constant (also called relative static permittivity) of the medium in the denominator of the equation ( is an electric constant):

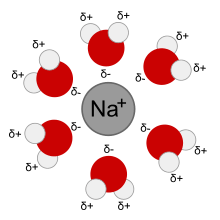

At an atomic level, the reduction in the force acting on a charge results from water molecules forming a hydration shell around it. This fact makes water a very good solvent for charged compounds like salts. Electric force which normally holds salt crystals together by way of ionic bonds is weakened in the presence of water allowing ions to separate from the crystal and spread through solution.

The same mechanism operates in the case of negatively charged phosphate groups on a DNA backbone: even though positive ions are present in solution, the relatively weak net electrostatic force prevents them from forming stable ionic bonds with phosphates and precipitating out of solution.

Ethanol is much less polar than water, with a dielectric constant of 24.3 (at 25 °C). This means that adding ethanol to solution disrupts the screening of charges by water. If enough ethanol is added, the electrical attraction between phosphate groups and any positive ions present in solution becomes strong enough to form stable ionic bonds and DNA precipitation. This usually happens when ethanol composes over 64% of the solution. As the mechanism suggests, the solution has to contain positive ions for precipitation to occur; usually Na+, NH4+ or Li+ plays this role .[1]

Practice

DNA is precipitated by first ensuring that the correct concentration of positive ions is present in solution (too much will result in a lot of salt co-precipitating with DNA, too little will result in incomplete DNA recovery) and then adding two to three volumes of at least 95% ethanol. Many protocols advise storing DNA at low temperature at this point, but there are also observation that it does not improve DNA recovery, and may even lower precipitation efficiency while using over-night incubation time.[2][3] In most cases, good efficiency is achieved at room temperature but when possible degradation is taken into account it is probably best to incubate DNA on wet ice. Optimal incubation time depends on the length and concentration of DNA. Smaller fragments and lower concentrations will require longer times to achieve acceptable recovery. For very small lengths and low concentrations over-night incubation is recommended. In such cases use of carriers like tRNA, glycogen or linear polyacrylamide can greatly improve recovery.

During incubation DNA and some salts will precipitate from solution, in the next step this precipitate is collected by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge tube at high speeds (~12,000g). Time and speed of centrifugation has the biggest effect on DNA recovery rates. Again smaller fragments and higher dilutions require longer and faster centrifugation. Centrifugation can be done either at room temperature or in 4 °C or 0 °C. During centrifugation precipitated DNA has to move through ethanol solution to the bottom of the tube, lower temperatures increase viscosity of the solution and larger volumes make the distance longer, so both those factors lower efficiency of this process requiring longer centrifugation for the same effect.[2][3] After centrifugation the supernatant solution is removed, leaving a pellet of crude DNA. Whether the pellet is visible depends on the amount of DNA and on its purity (dirtier pellets are easier to see) or the use of co-precipitants.

In the next step, 70% ethanol is added to the pellet, and it is gently mixed to break the pellet loose and wash it. This removes some of the salts present in the leftover supernatant and bound to DNA pellet making the final DNA cleaner. This suspension is centrifuged again to once again pellet DNA and the supernatant solution is removed. This step is repeated once.

Finally, the pellet is air-dried and the DNA is resuspended in water or other desired buffer. It is important not to over-dry the pellet as it may lead to denaturation of DNA and make it harder to resuspend.

Isopropanol can also be used instead of ethanol; the precipitation efficiency of the isopropanol is higher making one volume enough for precipitation. However, isopropanol is less volatile than ethanol and needs more time to air-dry in the final step. The pellet might also adhere less tightly to the tube when using isopropanol.[1]

Protocol

- Add 1/10 volume of sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2).

- Add 2.5–3.0 X volume (calculated after addition of sodium acetate) of at least 95% ethanol.

- Incubate on ice for 15 minutes. In case of small DNA fragments or high dilutions overnight incubation gives best results, incubation below 0 °C does not significantly improve efficiency.[2][3]

- Centrifuge at > 14,000 x g for 30 minutes at room temperature or 4 °C.

- Discard supernatant being careful not to throw out DNA pellet which may or may not be visible.

- Rinse with 70% ethanol

- Centrifuge again for 15 minutes.

- Discard supernatant and dissolve pellet in desired buffer. Make sure the buffer comes into contact with the whole surface of the tube since a significant portion of DNA may be deposited on the walls instead of in the pellet.[1]

See also

- DNA extraction

- Phenol–chloroform_extraction

- Spin column-based nucleic acid purification

- Salting in

- Salting out

- SCODA DNA purification

References

- 1 2 3 Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Third Edition) by Joseph Sambrook, Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Melbourne, Australia; David Russell, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas

- 1 2 3 Zeugin JA, Hartley JL (1985). "Ethanol Precipitation of DNA" (PDF). Focus. 7 (4): 1–2. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- 1 2 3 Crouse J, Amorese D (1987). "Ethanol Precipitation: Ammonium Acetate as an Alternative to Sodium Acetate" (PDF). Focus. 9 (2): 3–5. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

External links

- bitesizebio.com The Basics: How Ethanol Precipitation of DNA and RNA Works

- Zeugin JA, Hartley JL (1985). "Ethanol Precipitation of DNA" (PDF). Focus. 7 (4): 1–2. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- Crouse J, Amorese D (1987). "Ethanol Precipitation: Ammonium Acetate as an Alternative to Sodium Acetate" (PDF). Focus. 9 (2): 3–5. Retrieved 2008-09-10.