English cadence

In conventional classical music theory, the English cadence is a distinctive contrapuntal pattern particular to the authentic or perfect cadence described as archaic[1] or old-fashioned[2] sounding. This pattern is so named because of its use primarily by English composers of the High Renaissance and Restoration periods. The hallmark of this device is the dissonant augmented octave (compound augmented unison) produced by a false relation between the split seventh scale degree.

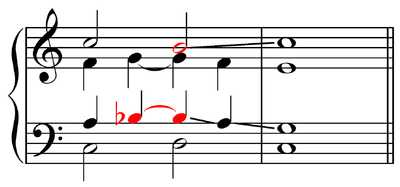

Popular with English composers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but named in the twentieth century, the English cadence is a type of full close featuring the blue seventh against the dominant chord[3] which in C would be B♭ and G–B♮–D.

Characteristics

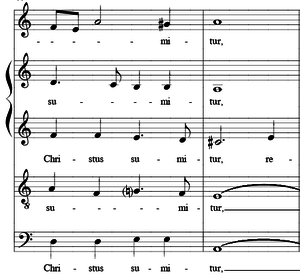

For instance, observe beat 4 of the example shown at right: the tenor's G♮ sounds concurrently with the soprano's G♯. This voice leading entails the seventh degree's dual functionality, or its capacity for opposing voice-leading tendencies. That is, a lowered seventh degree resolves downward to the sixth (e.g., G–F), while a raised seventh (i.e., a leading tone) resolves upward to the first degree (e.g., G♯–A).

In harmonic terms, the basis of the English cadence is the authentic cadence, which follows the chord progression V–I. This variant is characterized by a penultimate, dominant chord with a split third, thereby creating a false relation between the germane parts.

The contrapuntal nature of the device dictates a minimum of three parts, though it is generally found in works with four or more parts. Where this musical device is used in music written in a minor key, it is common for it to be combined with a Picardy third, ultimately producing a major tonic.

The Corelli cadence is another "clash cadence".

History and usage

The English cadence was primarily used in choral music, though it is also present in contemporaneous music for consorts of viols and other instruments.

The cadence is found as early as Machaut (c. 1300–1377).[5]

The origins of this cadential form are unclear. The end of Tallis's Spem in alium contains an example.[6]

Described as "stale" by Morley in 1597,[7] the device fell out of use in the early part of the seventeenth century, though we still find many examples of it in Purcell's anthems ("My heart is inditing" or "Rejoice in the Lord alway" for instance). This was due partly to a period of decline for music and composition in England, as well as to the development of generally accepted rules of harmony in which the false relation was no longer acceptable.

Sources

- ↑ Carver, Anthony (1988). The Development of Sacred Polychoral Music to the Time of Schütz, p.136. ISBN 0-521-30398-2. If the clash cadence is already, "archaic, [and/or] mannered," in the music of Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672) it must surely be so now.

- ↑ Herissone, Rebecca (2001). Music Theory in Seventeenth-Century England, p.170. ISBN 0-19-816700-8.

- ↑ van der Merwe, Peter (2005). Roots of the Classical: The Popular Origins of Western Music, p.492. ISBN 0-19-816647-8.

- ↑ Latham, Alison, ed. (2002). The Oxford Companion to Music, p.192. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- ↑ Apel, Willi and Binkley, Thomas (1990). Italian Violin Music of the Seventeenth Century, p.56. ISBN 0-253-30683-3.

- ↑ Diane Kelsey McColley (1998). Poetry and Music in Seventeenth-Century England, p.40. ISBN 0-521-59363-8.

- ↑ Curtis, Alan (1969). Sweelinck's Keyboard Music: A Study of English Elements in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Composition, p.155. 1987 edition: ISBN 90-04-08263-8.