Elands Bay Cave

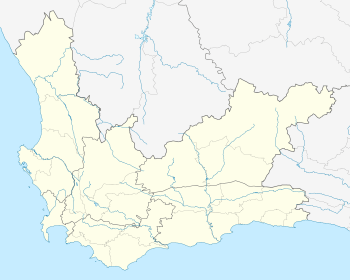

| Elands Bay Cave | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Elands Bay, Western Cape Province, South Africa |

| Coordinates | 32°19′03.5″S 18°19′04.6″E / 32.317639°S 18.317944°ECoordinates: 32°19′03.5″S 18°19′04.6″E / 32.317639°S 18.317944°E |

Elands Bay Cave is located near the mouth of the Verlorenvlei estuary on the Atlantic coast of South Africa's Western Cape Province.[1] The climate has continuously become drier since the habitation of hunter-gatherers in the Later Pleistocene. The archaeological remains recovered from previous excavations at Elands Bay Cave have been studied to help answer questions regarding the relationship of people and their landscape, the role of climate change that could have determined or influenced subsistence changes, and the impact of pastoralism and agriculture on hunter-gatherer communities.[2]

History of Research

Renowned archaeologist John Parkington excavated Elands Bay Cave in the 1970s providing vast information of the cave's inhabitants. Parkington frequently used methods of comparing various characteristics in his findings in order to highlight phases of transformations at Elands Bay Cave.[2] Other archaeologists and specialists have analyzed the findings from Parkington. Parkington, Cartwright, Cowling, Baxter, and Meadows (2000), analyzed wood charcoal and pollen data from Elands Bay Cave to explain the environmental change. Klein, in 2001 studied fossil remains and faunal data to indicate hunter-gatherer behavioral and cultural adaptations. In 1999, Cowling, Cartwright, Parkington, & Allsopp researched wood charcoal in order to explain environmental changes. Woodborne, Hart, & Parkington (1995) researched seal bones to construct the timing and the duration of hunter-gatherer coastal journeys. Orton (2006) examined raw materials to produce a lithic sequence for the Later Stone Age in Elands Bay Cave. Lastly, Matthews (1999) used taphonomy and previous research by Peter Andrews to understand the formation and interpretation of micromammals at Elands Bay Cave.

Environment

The coastline of Elands Bay Cave has changed dramatically since the end of the Ice Age.[1] A coastal plain once extended some 20 km west of Elands Bay Cave into the sea.[1] Heavier rainfall and different ocean levels allowed Elands Bay Cave to be a lush environment in the past. Testing of faunal remains, bones, and wood charcoals provided evidence of wetter conditions in the terminal Pleistocene. During that time, the environment consisted of colder weather with heavier rain fall which created vegetation that was different than it is today.[3] Now, it has become a drier environment with different species residing there. Rainfall from 9,600 to 13,600 years ago produced 400 mm comparable to today’s 300 mm.[4] More recent environmental conditions near Elands Bay Cave are characteristic of mild weather with an approximated 200–250 mm per year of rainfall occurring every winter.[4] Elands Bay Cave is in close proximity (approximately 3 kilometers) to a rich intertidal environment supporting numerous shellfish species, sea birds, kelp beds, and marine mammals.[5]

Over time, the climatic atmosphere near Elands Bay Cave became drier and the soil conditions turned to sand. Dense shrubs are maintained by older sand creating patches of subtropical plants in the area.[4] These environmental changes resulted in a reduction of available resources such as fresh water, mussels, and shellfish.

Transitions from the last glaciation to the Holocene had a significant impact on the type of vegetation and wildlife that could be supported along the southern coast.[6] Researchers suggest that because of increased aridity, the inhabitants of Elands Bay Cave abandoned the site and migrated elsewhere. Lack of archaeological remains concerning the dates of 8,000 to 4,400 and 4,000 BP support the theory of an occupation hiatus during these time frames.[6]

Excavations

Archaeological excavations at Elands Bay Cave began in the 1970s. Scientific interest has focused on investigating coastal changes, subsistence and seasonal mobility.[1] Faunal remains representing the time period of 13.600-12.000 years ago were left behind by the cave's occupants.[1] The majority of the faunal assemblage consists of grazing animals and is indicative of a grassland environment.[1] The faunal remains were examined and compared to collections at the South Africa Museum in Cape Town. Few marine specimens were recovered from this time span and is indicative of the 12 km distance from the cave to the coast.[1] Cartwright and Parkington (1997) excavated 6,700 fragments of wood charcoal that were retrieved through dry sieving large soil samples of 39 collections. Excavation of wood charcoal and pollen in the cave suggests that last glacial maximum had wetter conditions with lush forests and Afromontane elements 20,000 years ago.[3] There were also varieties of charcoal tested from 20,000, 13,500, and 10,500 years ago. Researchers have also analyzed micromammals, such as mice, as paleoenvironmental indicators.[7] Micromammal remains were encountered during excavations and occur throughout the units dating from 13,260 to 300 years before present.[7] The micromammal specimens were recovered using 12mm and 3mm sieves, however, the researchers comment that this mesh size was likely too large to account for smaller faunal remains.[7] Understanding the taphonomic processes that contributed to the deposition of the micromammal remains at Elands Bay Cave is important because it has identified a number of predators likely responsible for the accumulation of faunal material.[7] that became a great tool for formation of micromammal collection.[7] Excavations in Elands Bay Cave and surrounding areas support a hypothesis of migration in winter months. Assemblages of shellfish findings portray that the theory of shellfish changing in size during prehistoric times because of environment was overthrown and was replaced by consuming large amounts of shellfish at the time. Observations and excavations were done in Elands Bay Cave in order to properly identify species of fish bones with accurate representation in specific levels. Excavations that were conducted from 1970 to 1978 in Elands Bay Cave concluded that there was a stratified sequence of deposits that dated to the late Pleistocene.[8] Between 8000 and 6000 years ago, the rise in sea level eventually resulted in the present location of Elands Bay Cave now on the coast.[1] Excavations after 4,000 BP revealed there were 13 different species of fish represented at the site, 6 of which are still found today in the aquatic milieus.[8] These findings supported the conclusion that due to the close proximity to the coast, fishing activities were the dominant subsistence strategy practiced by the people who occupied Elands Bay Cave.[1] With the coastline in its present-day location by about 6000 years ago, the inhabitants of the cave were thus in a favorable location to exploit marine resources.[1]

Stratigraphy and Dating

There are 60 radiocarbon dates that represent activity during the Holocene, a large part of the terminal Pleistocene, and also the last glacial maximum.[9] Stratigraphy dating and the Middle Stone Age artifacts are at the base, then ashy loam's before 20,000 years ago BP, lastly topped with shell middens. Upper shell middens range from 3,800 to 300 BP, though there was a disturbance of accumulation from 7,900 years ago that stopped for about 4,000 years. Around 11,000 to 9,000 years ago the terrestrial fauna began to change. Shell middens from the Holocene are on top of Pleistocene soil that was accumulated from the last glacial period.[9] Prior to 9,000 BP, seals do not appear to be seasonal at Elands Bay Cave. The seal collection was divided into two collections: upper ranging from 1,400 BP and lower ranging from 10,000 BP to 9,500 BP.[10] Charcoal that was 40,000 years old was studied. Proteoid fynbos was able to be harvested because of improved soils in 12,450 BP to 13,600 BP. In the terminal Pleistocene, approximately 16,000 to 8,000 years ago, ostrich egg shells and animal bones were introduced to the cave. Establishment of non-micro lithic industry was discovered to be from 10,000 BP continuing on to 8900 BP.[11] It is found that major increase of formal tools took place in 9,500 BP.[11] The transitions of tool assemblages in Elands Bay Cave are assumed to be from 8,800 to 8,500 BP.[11] In 8,000 BP Holocene, Elands Bay Cave had microlithics for the first time. Radiocarbon dates indicate that Albany Industry was in use circa 13,000 and 9,000 BP.[6]

Findings

Artefacts and Faunal Remains

Elands Bay Cave is perceived as the central site because it includes the largest sample sizes and covers more time spans.[6] Elands Bay Cave has been used at different times for various purposes; evidence found at the cave suggests that there is a series of overlapping events that are in no constant order. The research that has been done in the cave concludes that people lived there around 4,400 to 3,000 years ago and that hunting and gathering activities persisted until the 17th century AD. Migration patterns were found due to shell midden evidence from marine resources archaeologists found displaying exploitation from that time. All the research contributes in various ways of monitoring stratigraphic anomalies within Elands Bay Cave.

Culture

Group sizes varied at different points, some were just a few families and at other times there could have been up to 100 people. Either way, a community was built. Hunter-gatherers became more advanced in the Later Stone age compared to the Middle Stone Age. Expansion of hearths found inside Elands Bay Cave illustrates that people were skillful with fire. It also indicates cultural evolution by gathering together when it was dark or cold outside. They also discovered that hunter-gatherers stored food underground in containers and used ostrich eggs as portable water vessels. People from the Later Stone Age seemed to have gathered the most remains from fish and aerial birds which indicate artefactual observation conclusion of people fishing and fowling routinely.[12]

Seal Bones

Seal mandibles that were found at the cave were compared to mandibles from South Africa Museum and Department of Sea Fisheries Collection. The upper division of seals collection explained that seals were hunted during winter and spring months. This implies that hunter-gatherers would purposefully plan to be at the Elands Bay Cave at those times. The lower collection finds that there was no seasonal correlation to habitation and that the seals were 2 years old. The study of seal mandibles aid in gaining understanding of deaths and predict probable seasonal migration. Through carbon isotope testing, upper level dating of seal bones were found to not be consistent with findings of human remains at the same time. These findings were all to demonstrate that the cave was accessible and used to easily capture seals pups. Animal bones demonstrate drastic change in vegetation. Seal bones are plentiful after 11,000 to 10,000 BP.[6] Bones used to identify seals in Elands Bay Cave are mainly the remains of limb bones, such as the humeri. These bone types can be distinguished from other wildlife skeletal remains because they lack a marrow cavity. During 11,000 to 10,000 BP sea levels rose, this allowed seals to be exploited through hunting.[4]

Wood and Pollen Findings

Before 4,000 BP people from Elands Bay Cave would gather wood from moister plants that would grow in different areas.[4] Pollen in small denominations is discovered from the last glacial maximum but none from past that time.[4] This is presented through the connection of higher moisture availability supporting fuel wood accessibility and variety. Samples of wood charcoal and pollen that are 17,000 to 20,000 years old (terminal Pleistocene) show a connection to vegetation rather than rainfall. Recent charcoal resembles xeric thicket and states that vegetation was more diverse.[3] There is a drainage system that has gone through Elands Bay Cave, the Velorenvlei. It is speculated that the connection from that drainage system to Elands Bay Cave has a significant impact on the collection of pollen that is found in Elands Bay Cave.[4] It is revealed that the moisture in the soil has been deteriorating from at least 4,000 years ago; other observations conclude similar findings because of evidence from pollen and faunal remains from the same epochs.[4]

Middens

The stratigraphy of Elands Bay Cave is dominated by shell midden as well as levels composed of ashy matrix interpreted as living floor features containing remnants of grasses possibly used as bedding, bone and shell.[5] There was 40 cubic meters of shell middens found from the Holocene period. Aside from mussel shells, middens consisted of ostrich shells and other marine shells.[13] It was discovered that ostrich eggs, used as water containers, were sometimes repurposed as beads after breaking. Some wood charcoal from 40,000 years ago from the terminal Holocene (300 years ago) to early late Pleistocene revealed that it was beyond range of carbon dating. There was only 25-44 g/m3 microfaunal found.[7] In early Holocene, limpets were the dominant species represented within the midden levels. Four stratigraphic levels were observed throughout the middens and were documented. Stages 1,2, and 3 are the top three levels; they are believed to be dated to around 1,500 to 600 BP.[6] The lower stage, level 4, is understood to be dated no older that 1,500 BP.[6]

Taphonomy

Archeological evidence supports taphonomy investigations in order to rule out assumptions of extinction or depletion of wildlife. It is important to identify who the predator is before environment analysis. It was found that the study of taphonomy was important because it allowed researchers to distinguish the factors responsible for the collection and establishment of habits and behaviors of different species. Researchers discovered that predator species contributed to micromammal accumulations and with this, helped recreate the environment they lived in. Remains from different predator birds show that the Barn Owl was not the only airborne wildlife using the cave as a shelter.[7] Additional suspect predators include different owl species such as the spotted eagle owl, the giant owl, the Cape eagle owl, as well the black backed jackal and the grey mongoose.[7]

Bones

There were remains of sheep bones found at Elands Bay Cave between 2,000 and 1,500 BP. The first bone collectors in Elands Bay Cave were discovered to be people from the Stone Age.[6] Some bones were gnawed and chewed, which predicted the habitation of carnivores and porcupines.[6] Evidence suggests that mole rats could have been introduced by people bringing them when they migrated to Elands Bay Cave or, the more likely suggestion is that they were brought by Eagle owls after 10,000 BP. There are fluctuations in evidence which are reflections of periods when the owls used the cave. Fossil samples from mole rat humeri’s were collected and tested. Jaws and foot bones are the most common bones used to identify species since they are long-lasting and easy to identify even when in pieces.[6] Over time there was a reduction in mole rat sizes in the collections, likely because of weather and environmental changes. This would explain the appearance of certain animals like hedgehogs since they favor wetter climates. Some animals such as the Cape horse became extinct and others like the hedgehog came about. This could be seen through fossils found in soil deposits.

Fish

Fish species within the faunal assemblage recovered from Elands Bay Cave increased over time and represent both estuary and marine varieties.[8] This is a reflection of higher sea levels from the conversion of the last glaciation to the Holocene.[6] Excavations from 1970 to 1978, revealed that the white steenbras was the most prevalent fish specie.[8] The varying size of the white steenbras over time may reflect a fishing technology that employed the use of fish gorges.[8] Layers where bone gorges were present typically were void of small age classes.[8] Fish species remained relatively unchanged throughout the Holocene levels, with the most common type being the Sparidae.[8]

Shellfish

Shellfish remains discovered after 4,000 BP indicate an increase in marine resource exploitation and represents a shift away from mammals as the dietary staple.[8] This was produced because the coastline became part of the cave’s basin. A high percentage, 90%, of shell middens from the Holocene period were black mussels.[14] These types of findings in an area would indicate a settlement with shellfish being a large portion of their daily nutritional intake. In Elands Bay Cave there were three main shell middens remains: Black mussels, and two different classes of limpets.[14] The shells that were found had not reached full adulthood within the cave, which leads archaeologists to believe that they were an essential part of their diet.[14] There were notable different sizes outside the cave but it is speculated that it is because of the consumption inside the cave that the mussels were accessible and therefore, there was a slim chance for the shellfish to reach mature age.

Artefacts

Stone Tools

Until 9,000 years ago in the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, stone tools were made out of quartz. There was an abundance of vein quartz, even if found in small forms like pebbles. Even though the principal material of the tools was quartz, other materials were also found in sizable quantities.[11] These include a substantial amount of hornfels, tough siltstones, and dolerite.[15] Aside from quartz and silcrete, the other materials are unknown on how they got to the location. Quality raw materials are suspected to have been brought from other regions. It is also suggested that they could have manifested through trade or simply carried in from migration.

Discussion

Elands Bay Cave was not always occupied. There are conflicting theories of seasonal migration to the cave just like in the Early Holocene. Yet, lack of evidence of seals in Elands Bay Cave at that time leads some to suggest that it was not a seasonal habitation. Since there are no signs of transitions even with the vast diverse archeologically evidence of faunal and artifact remains, it suggests to some that people did live there for a long time not just occasionally. Hunter-gatherers were able to understand and use the land at a local and regional scale. This is demonstrated with the large amount of seal evidence in faunal collection in the terminal Pleistocene. Migration could have been an occurrence because of harsh weather and less agricultural resources which would lead them to find a location that produced more dietary supplements.

Although charcoal analysis proved faunal diversity, more research is needed to close gaps in charcoal records. Changing behavior, creating culture, and emergence of new systems need to still be studied in depth in order to gain a greater sense of the historical Elands Bay Cave community.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul (2012). Archaeology Theories, Methods, and Practice (6th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. p. 253.

- 1 2 Parkington, John (1988). "The Pleistocene/Holocene transition in the Western Cape, South Africa, observations from Verlorenvlei". BAR International Series. 405: 197–206.

- 1 2 3 Parkington, J., Cartwright, C., Cowling, R. M., Baxter, A., & Meadows, M (2000). "Palaeovegetation at the last glacial maximum in the Western Cape, South Africa: wood charcoal and pollen evidence from Elands Bay Cave" (PDF). South African Journal of Science. 96: 543–546.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cowling, R. M.; Cartwright, C. R.; Parkington, J. E.; Allsopp, J. C. (1999). "Fossil wood charcoal assemblages from Elands Bay Cave, South Africa: implications for Late Quaternary vegetation and climates in the winter-rainfall fynbos biome". Journal of Biogeography. 26 (2): 367–378. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00275.x.

- 1 2 Parkington, John (1972). "Seasonal Mobility in the Later Stone Age". Africa Studies (31): 223–43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Klein, R. G., & Cruz-Uribe, K (1987). "Large mammal and tortoise bones from Elands Bay Cave and nearby sites, western Cape Province, South Africa". Papers in the Prehistory of the Western Cape, South Africa. 132: 163.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Matthews, Thalassa (1999). "Taphonomy and the micromammals from Elands Bay Cave". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 54 (170): 133–140. doi:10.2307/3889292. JSTOR 3889292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Poggenpoel, C. A. (1987). "The implications of fish bone assemblages from Eland's Bay Cave, Tortoise Cave and Diepkloof for changes in the Holocene history of Verlorenvlei". Papers in the Prehistory of the Western Cape, South Africa. 322: 217.

- 1 2 Cartwright, Caroline; Parkington, John (1997). "The wood charcoal assemblages from Elands Bay Cave, southwestern Cape: principles, procedures and preliminary interpretation". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 52 (165): 59–72. doi:10.2307/3888977. JSTOR 3888977.

- ↑ Woodborne, Stephan; Hart, Ken; Parkington, John (1995). "Seal bones as indicators of the timing and duration of hunter-gatherer coastal visits". Journal of Archaeological Science. 22 (6): 727–740. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(95)90003-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Orton, Jayson (2006). "The Later Stone Age lithic sequence at Elands Bay, Western Cape, South Africa: raw materials, artefacts and sporadic change". Southern African Humanities. 18 (2): 1–28.

- ↑ Klein, R. (2001). "Southern Africa and modern human origins". Journal of Anthropological Research. 57 (1): 1–16. JSTOR 3630795.

- ↑ Parkington, John (1976). "Coastal settlement between the mouths of the Berg and Olifants Rivers, Cape Province". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 31 (123/124): 127–140. doi:10.2307/3887733. JSTOR 3887733.

- 1 2 3 Buchanan, W. F.; Hall, S. L.; Henderson, J.; Olivier, A.; Pettigrew, J. M.; Parkington, J. E.; Robertshaw, P. T. (1978). "Coastal shell middens in the Paternoster area, south-western Cape". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 33 (127): 89–93. doi:10.2307/3888255. JSTOR 3888255.

- ↑ Bailey, G., & Parkington, J (1988). The archaeology of prehistoric coastlines. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 25036 6.