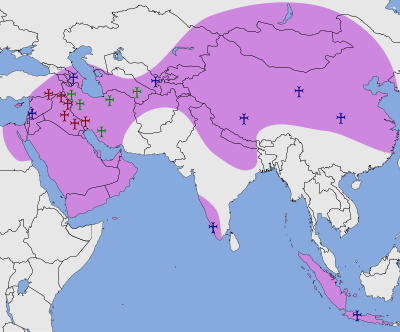

Dioceses of the Church of the East to 1318

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Liturgy and worship |

|

At the height of its power, in the 10th century AD, the dioceses of the Church of the East numbered well over a hundred and stretched from Egypt to China. These dioceses were organised into six interior provinces in Mesopotamia, in the Church's Iraqi heartland, and a dozen or more second-rank exterior provinces. Most of the exterior provinces were located in Iran, Central Asia, India and China, testifying to the Church's remarkable eastern expansion in the Middle Ages. A number of East Syrian dioceses were also established in the towns of the eastern Mediterranean, in Palestine, Syria, Cilicia and Egypt.

Sources

There are few sources for the ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East before the Sassanian (Persian) period, and the information provided in martyr acts and local histories such as the Chronicle of Erbil may not always be genuine. The Chronicle of Erbil, for example, provides a list of East Syrian dioceses supposedly in existence by 225. References to bishops in other sources confirm the existence of many of these dioceses, but it is impossible to be sure that all of them had been founded at this early period. Diocesan history was a subject particularly susceptible to later alteration, as bishops sought to gain prestige by exaggerating the antiquity of their dioceses, and such evidence for an early diocesan structure in the Church of the East must be treated with great caution. Firmer ground is only reached with the 4th-century narratives of the martyrdoms of bishops during the persecution of Shapur II, which name several bishops and dioceses in Mesopotamia and elsewhere.

The ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East in the Sassanian period, at least in the interior provinces and from the 5th century onwards, is known in some detail from the records of synods convened by the patriarchs Isaac in 410, Yahballaha I in 420, Dadishoʿ in 424, Acacius in 486, Babaï in 497, Aba I in 540 and 544, Joseph in 554, Ezekiel in 576, Ishoʿyahb I in 585 and Gregory in 605.[1] These documents record the names of the bishops who were either present at these gatherings, or who adhered to their acts by proxy or later signature. These synods also dealt with diocesan discipline, and throw interesting light on the problems which the leaders of the church faced in trying to maintain high standards of conduct among their widely dispersed episcopate.

After the Arab conquest in the 7th century, the sources for the ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East are of a slightly different nature from the synodical acts and historical narratives of the Sassanian period. As far as its patriarchs are concerned, reign-dates and other dry but interesting details have often been meticulously preserved, giving the historian a far better chronological framework for the Ummayad and ʿAbbasid periods than for the Mongol and post-Mongol periods. The 11th-century Chronography of Eliya Bar Shinaya, edited in 1910 by E. W. Brooks and translated into Latin (Eliae Metropolitae Nisibeni Opus Chronologicum), recorded the date of consecration, length of reign and date of death of all the patriarchs from Timothy I (780–823) to Yohannan V (1001–11), and also supplied important information on some of Timothy's predecessors.

Valuable additional information on the careers of the East Syrian patriarchs is supplied in histories of the Church of the East since its foundation written by the 12th-century East Syrian author Mari ibn Sulaiman and the 14th-century authors ʿAmr ibn Mattai and Sliba ibn Yuhanna. Mari's history, written in the second half of the 12th century, ends with the reign of the patriarch ʿAbdishoʿ III (1139–48). The 14th-century writer ʿAmr ibn Mattai, bishop of Tirhan, abridged Mari's history but also provided a number of new details and brought it up to the reign of the patriarch Yahballaha III (1281–1317). Sliba, in turn, continued ʿAmr's text into the reign of the patriarch Timothy II (1318 – c. 1332). Unfortunately, no English translation has yet been made of these important sources. They remain available only in their original Arabic, and in a Latin translation (Maris, Amri, et Salibae: De Patriarchis Nestorianorum Commentaria) made between 1896 and 1899 by their editor, Enrico Gismondi.

There are also a number of valuable references to the Church of the East and its bishops in the Chronicon Ecclesiasticum of the 13th-century West Syrian writer Bar Hebraeus. Although principally a history of the Syrian Orthodox Church, the Chronicon Ecclesiasticum frequently mentions developments in the East Syrian church that affected the West Syrians. Like its East Syrian counterparts, the Chronicon Ecclesiasticum has not yet been translated into English, and remains available only in its Syriac original and in a Latin translation (Bar Hebraeus Chronicon Ecclesiasticum) made in 1877 by its editors, Jean Baptiste Abbeloos and Thomas Joseph Lamy.

Rather less is known about the diocesan organisation of the Church of the East under the caliphate than during the Sassanian period. Although the acts of several synods held between the 7th and 13th centuries were recorded (the 14th-century author ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis mentions the acts of the synods of Ishoʿ Bar Nun and Eliya I, for example), most have not survived. The synod of the patriarch Gregory in 605 was the last ecumenical synod of the Church of the East whose acts have survived in full, though the records of local synods convened at Dairin in Beth Qatraye by the patriarch Giwargis in 676 and in Adiabene in 790 by Timothy I have also survived by chance.[2] The main sources for the episcopal organisation of the Church of the East during the Ummayad and ʿAbbasid periods are the histories of Mari, ʿAmr and Sliba, which frequently record the names and dioceses of the metropolitans and bishops present at the consecration of a patriarch or appointed by him during his reign. These records tend to be patchy before the 11th century, and the chance survival of a list of bishops present at the consecration of the patriarch Yohannan IV in 900 helps to fill one of the many gaps in our knowledge.[3] The records of attendance at patriarchal consecrations must be used with caution, however, as they can give a misleading impression. They inevitably gave prominence to the bishops of Mesopotamia and overlooked those of the more remote dioceses who were unable to be present. These bishops were often recorded in the acts of the Sassanian synods, because they adhered to their acts by letter.

Two lists in Arabic of East Syrian metropolitan provinces and their constituent dioceses during the ʿAbbasid period have survived. The first, reproduced in Assemani's Bibliotheca Orientalis, was made in 893 by the historian Eliya of Damascus.[4] The second, a summary ecclesiastical history of the Church of the East known as the Mukhtasar al-akhbar al-biʿiya, was compiled in 1007/8. This history, published by B. Haddad (Baghdad, 2000), survives in an Arabic manuscript in the possession of the Chaldean Church, and the French ecclesiastical historian J. M. Fiey made selective use of it in Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus (Beirut, 1993), a study of the dioceses of the West and East Syrian churches.

A number of local histories of monasteries in northern Mesopotamia were also written at this period (in particular Thomas of Marga’s Book of Governors, the History of Rabban Bar ʿIdta, the History of Rabban Hormizd the Persian, the History of Mar Sabrishoʿ of Beth Qoqa and the Life of Rabban Joseph Busnaya) and these histories, together with a number of hagiographical accounts of the lives of notable holy men, occasionally mention bishops of the northern Mesopotamian dioceses.

Thomas of Marga is a particularly important source for the second half of the 8th century and the first half of the 9th century, a period for which little synodical information has survived and also few references to the attendance of bishops at patriarchal consecrations. As a monk of the important monastery of Beth ʿAbe, and later the secretary of the patriarch Abraham II (832–50), he had access to a wide range of written sources, including the correspondence of the patriarch Timothy I, and could also draw on the traditions of his old monastery and the long memories of its monks. Thirty or forty otherwise unattested bishops of this period are mentioned in the Book of Governors, and it is the prime source for the existence of the northern Mesopotamian diocese of Salakh. A particularly important passage mentions the prophecy of the monastery’s superior Quriaqos, who flourished around the middle of the 8th century, that forty-two of the monks under his care would later become bishops, metropolitans, or even patriarchs. Thomas was able to name, and supply interesting information about, thirty-one of these bishops.[5]

Nevertheless, references to bishops beyond Mesopotamia are infrequent and capricious. Furthermore, many of the relevant sources are in Arabic rather than Syriac, and often use a different Arabic name for a diocese previously attested only in the familiar Syriac form of the synodical acts and other early sources. Most of the Mesopotamian dioceses can be readily identified in their new Arabic guise, but on occasion the use of Arabic presents difficulties of identification.

Parthian period

By the middle of the 4th century, when many of its bishops were martyred during the persecution of Shapur II, the Church of the East probably had twenty or more dioceses within the borders of the Sassanian empire, in Beth Aramaye (ܒܝܬ ܐܪܡܝܐ), Beth Huzaye (ܒܝܬ ܗܘܙܝܐ), Maishan (ܡܝܫܢ), Adiabene (Hdyab, ܚܕܝܐܒ) and Beth Garmaï (ܒܝܬܓܪܡܝ), and possibly also in Khorasan. Some of these dioceses may have been at least a century old, and it is possible that many of them were founded before the Sassanian period. According to the Chronicle of Erbil there were several dioceses in Adiabene and elsewhere in the Parthian empire as early as the end of the 1st century, and more than twenty dioceses in 225 in Mesopotamia and northern Arabia, including the following seventeen named dioceses: Bēṯ Zaḇdai (ܒܝܬ ܙܒܕܝ), Karkhā d-Bēṯ Slōkh (ܟܪܟܐ ܕܒܝܬ ܣܠܘܟ), Kaškar (ܟܫܟܪ), Bēṯ Lapaṭ (ܒܝܬ ܠܦܛ), Hormīzd Ardašīr (ܗܘܪܡܝܙܕ ܐܪܕܫܝܪ), Prāṯ d-Maišān (ܦܪܬ ܕܡܝܫܢ), Ḥnīṯā (ܚܢܝܬܐ), Ḥrḇaṯ Glāl (ܚܪܒܬ ܓܠܠ), Arzun (ܐܪܙܘܢ), Beth Niqator (apparently a district in Beth Garmaï), Shahrgard, Beth Meskene (possibly Piroz Shabur, later an East Syrian diocese), Hulwan (ܚܘܠܘܐܢ), Beth Qatraye (ܒܝܬ ܩܛܪܝܐ), Hazza (probably the village of that name near Erbil, though the reading is disputed), Dailam and Shigar (Sinjar). The cities of Nisibis (ܢܨܝܒܝܢ) and Seleucia-Ctesiphon, it was said, did not have bishops at this period because of the hostility of the pagans towards an overt Christian presence in the towns. The list is plausible, though it is perhaps surprising to find dioceses for Hulwan, Beth Qatraye, Dailam and Shigar so early, and it is not clear whether Beth Niqator was ever an East Syrian diocese.

Sassanid period

During the 4th century the dioceses of the Church of the East began to group themselves into regional clusters, looking for leadership to the bishop of the chief city of the region. This process was formalised at the synod of Isaac in 410, which first asserted the priority of the 'grand metropolitan' of Seleucia-Ctesiphon and then grouped most of the Mesopotamian dioceses into five geographically-based provinces (by order of precedence, Beth Huzaye, Nisibis, Maishan, Adiabene and Beth Garmaï), each headed by a metropolitan bishop with jurisdiction over several suffragan bishops. Canon XXI of the synod foreshadowed the extension of this metropolitan principle to a number of more remote dioceses in Fars, Media, Tabaristan, Khorasan and elsewhere.[6] In the second half of the 6th century the bishops of Rev Ardashir and Merv (and possibly Herat) also became metropolitans. The new status of the bishops of Rev Ardashir and Merv was recognised at the synod of Joseph in 554, and henceforth they took sixth and seventh place in precedence respectively after the metropolitan of Beth Garmaï. The bishop of Hulwan became a metropolitan during the reign of Ishoʿyahb II (628–45). The system established at this synod survived unchanged in its essentials for nearly a millennium. Although during this period the number of metropolitan provinces increased as the church’s horizons expanded, and although some suffragan dioceses within the original six metropolitan provinces died out and others took their place, all the metropolitan provinces created or recognised in 410 were still in existence in 1318.

Interior provinces

Province of the Patriarch

The patriarch himself sat at Seleucia-Ctesiphon or, more precisely, the Sassanian foundation of Veh-Ardashir on the west bank of the Tigris, built in the 3rd century adjacent to the old city of Seleucia, which was thereafter abandoned. Ctesiphon, founded by the Parthians, was nearby on the east bank of the Tigris, and the double city was always known by its early name Seleucia-Ctesiphon to the East Syrians. It was not normal for the head of an eastern church to administer an ecclesiastical province in addition to his many other duties, but circumstances made it necessary for Yahballaha I to assume responsibility for a number of dioceses in Beth Aramaye.

The dioceses of Kashkar, Zabe, Hirta (al-Hira), Beth Daraye and Dasqarta d'Malka (the Sassanian winter capital Dastagird), doubtless because of their antiquity or their proximity to the capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon, were reluctant to be placed under the jurisdiction of a metropolitan, and it was felt necessary to treat them tactfully. A special relationship between the diocese of Kashkar, believed to have been an apostolic foundation, and the diocese of Seleucia-Ctesiphon was defined in Canon XXI of the synod of 410:

The first and chief seat is that of Seleucia and Ctesiphon; the bishop who occupies it is the grand metropolitan and chief of all the bishops. The bishop of Kashkar is placed under the jurisdiction of this metropolitan; he is his right arm and minister, and he governs the diocese after his death.[7]

Although the bishops of Beth Aramaye were admonished in the acts of these synods, they persisted in their intransigence, and in 420 Yahballaha I placed them under his direct supervision. This ad hoc arrangement was later formalised by the creation of a 'province of the patriarch'. As foreshadowed in the synod of Isaac in 410, Kashkar was the highest ranking diocese in this province, and the bishop of Kaskar became the 'guardian of the throne' (natar kursya) during the interregnum between one patriarch's death and the election of his successor. The diocese of Dasqarta d'Malka is not mentioned again after 424, but bishops of the other dioceses were present at most of the 5th- and 6th-century synods. Three more dioceses in Beth Aramaye are mentioned in the acts of the later synods: Piroz Shabur (first mentioned in 486); Tirhan (first mentioned in 544); and Shenna d'Beth Ramman or Qardaliabad (first mentioned in 576). All three dioceses were to have a long history.

Province of Beth Huzaye (Elam)

The metropolitan of Beth Huzaye (ʿIlam or Elam), who resided in the town of Beth Lapat (Veh az Andiokh Shapur), enjoyed the right of consecrating a new patriarch. In 410 it was not possible to appoint a metropolitan for Beth Huzaye, as several bishops of Beth Lapat were competing for precedence and the synod declined to choose between them.[8] Instead, it merely laid down that once it became possible to appoint a metropolitan, he would have jurisdiction over the dioceses of Karka d'Ledan, Hormizd Ardashir, Shushter (Shushtra, ܫܘܫܛܪܐ) and Susa (Shush, ܫܘܫ). These dioceses were all founded at least a century earlier, and their bishops were present at most of the synods of the 5th and 6th centuries. A bishop of Ispahan was present at the synod of Dadishoʿ in 424, and by 576 there were also dioceses for Mihraganqadaq (probably the 'Beth Mihraqaye' included in the title of the diocese of Ispahan in 497) and Ram Hormizd (Ramiz).

Province of Nisibis

In 363 the Roman emperor Jovian was obliged to cede Nisibis and five neighbouring districts to Persia to extricate the defeated army of his predecessor Julian from Persian territory. The Nisibis region, after nearly fifty years of rule by Constantine and his Christian successors, may well have contained more Christians than the entire Sassanian empire, and this Christian population was absorbed into the Church of the East in a single generation. The impact of the cession of Nisibis on the demography of the Church of the East was so marked that the province of Nisibis was ranked second among the five metropolitan provinces established at the synod of Isaac in 410, a precedence apparently conceded without dispute by the bishops of the three older Persian provinces relegated to a lower rank.

The bishop of Nisibis was recognised in 410 as the metropolitan of Arzun (ܐܪܙܘܢ), Qardu (ܩܪܕܘ), Beth Zabdaï (ܒܝܬ ܙܒܕܝ), Beth Rahimaï (ܒܝܬ ܪܚܡܝ) and Beth Moksaye (ܒܝܬ ܡܘܟܣܝܐ). These were the Syriac names for Arzanene, Corduene, Zabdicene, Rehimene and Moxoene, the five districts ceded by Rome to Persia in 363.[8] The metropolitan diocese of Nisibis (ܢܨܝܒܝܢ) and the suffragan dioceses of Arzun, Qardu and Beth Zabdaï were to enjoy a long history, but Beth Rahimaï is not mentioned again, while Beth Moksaye is not mentioned after 424, when its bishop Atticus (probably, from his name, a Roman) subscribed to the acts of the synod of Dadishoʿ. Besides the bishop of Arzun, a bishop of 'Aoustan d’Arzun' (plausibly identified with the district of Ingilene) also attended these two synods, and his diocese was also assigned to the province of Nisibis. The diocese of Aoustan d'Arzun survived into the 6th century, but is not mentioned after 554.

During the 5th and 6th centuries three new dioceses in the province of Nisibis were founded in Persian territory, in Beth ʿArabaye (the hinterland of Nisibis, between Mosul and the Tigris and Khabur rivers) and in the hill country to the northeast of Arzun. By 497 a diocese had been established at Balad (the modern Eski Mosul) on the Tigris, which persisted into the 14th century.[9] By 563 there was also a diocese for Shigar (Sinjar), deep inside Beth ʿArabaye, and by 585 a diocese for Kartwaye, the country to the west of Lake Van inhabited by the Kartaw Kurds.[10]

The famous School of Nisibis was an important seminary and theological academy of the Church of the East during the late Sassanian period, and in the last two centuries of Sassanian rule generated a remarkable outpouring of East Syrian theological scholarship.

Province of Maishan

In southern Mesopotamia, the bishop of Prath d'Maishan (ܦܪܬ ܕܡܝܫܢ) became metropolitan of Maishan (ܡܝܫܢ) in 410, responsible also for the three suffragan dioceses of Karka d'Maishan (ܟܪܟܐ ܕܡܝܫܢ), Rima (ܪܝܡܐ) and Nahargur (ܢܗܪܓܘܪ). The bishops of these four dioceses attended most of the synods of the 5th and 6th centuries.[11]

Province of Adiabene

_of_Hewl%C3%AAr_(Erbil).jpg)

The bishop of Erbil became metropolitan of Adiabene in 410, responsible also for the six suffragan dioceses of Beth Nuhadra (ܒܝܬ ܢܘܗܕܪܐ), Beth Bgash, Beth Dasen, Ramonin, Beth Mahqart and Dabarin.[8] Bishops of the dioceses of Beth Nuhadra, Beth Bgash and Beth Dasen, which covered the modern ʿAmadiya and Hakkari regions, were present at most of the early synods, and these three dioceses continued without interruption into the 13th century. The other three dioceses are not mentioned again, and have been tentatively identified with three dioceses better known under other names: Ramonin with Shenna d'Beth Ramman in Beth Aramaye, on the Tigris near its junction with the Great Zab; Beth Mahrqart with Beth Qardu in the Nisibis region, across the Tigris from the district of Beth Zabdaï; and Dabarin with Tirhan, a district of Beth Aramaye which lay between the Tigris and the Jabal Ḥamrin, to the southwest of Beth Garmaï.

By the middle of the 6th century there were also dioceses in the province of Adiabene for Maʿaltha (ܡܥܠܬܐ) or Maʿalthaya (ܡܥܠܬܝܐ), a town in the Hnitha (ܚܢܝܬܐ) or Zibar district to the east of ʿAqra, and for Nineveh. The diocese of Maʿaltha is first mentioned in 497, and the diocese of Nineveh in 554, and bishops of both dioceses attended most of the later synods.[12]

Province of Beth Garmaï

The bishop of Karka d'Beth Slokh (ܟܪܟܐ ܕܒܝܬ ܣܠܘܟ, modern Kirkuk) became metropolitan of Beth Garmaï, responsible also for the five suffragan dioceses of Shahrgard, Lashom (ܠܫܘܡ), Mahoze d'Arewan (ܡܚܘܙܐ ܕܐܪܝܘܢ), Radani and Hrbath Glal (ܚܪܒܬܓܠܠ). Bishops from these five dioceses are found at most of the synods in the 5th and 6th centuries.[8] Two other dioceses also existed in the Beth Garmaï district in the 5th century which do not appear to have been under the jurisdiction of its metropolitan. A diocese existed at Tahal as early as 420, which seems to have been an independent diocese until just before the end of the 6th century, and bishops of the Karme district on the west bank of the Tigris around Tagrit, in later centuries a West Syrian stronghold, were present at the synods of 486 and 554.

Unlocalised dioceses

Several dioceses mentioned in the acts of the early synods cannot be convincingly localised. A bishop Ardaq of 'Mashkena d'Qurdu' was present at the synod of Dadishoʿ in 424, a bishop Mushe of 'Hamir' at the synod of Acacius in 486, bishops of 'Barhis' at the synods of 544, 576 and 605, and a bishop of ʿAïn Sipne at the synod of Ezekiel in 576. Given the personal attendance of their bishops at these synods, these dioceses were probably in Mesopotamia rather than the exterior provinces.[13]

Exterior provinces

Canon XXI of the synod of 410 provided that 'the bishops of the more remote dioceses of Fars, the Islands, Beth Madaye [Media], Beth Raziqaye [Rai] and also the country of Abrashahr [Nishapur], must later accept the definition established in this council'.[6] This reference demonstrates that the influence of the Church of the East in the 5th century had extended beyond the non-Iranian fringes of the Sassanian empire to include several districts within Iran itself, and had also spread southwards to the islands off the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf, which were under Sassanian control at this period. By the middle of the 6th century the Church's reach seems to have spread well beyond the frontiers of the Sassanian empire, as a passage in the acts of the synod of Aba I in 544 refers to East Syrian communities 'in every district and every town throughout the territory of the Persian empire, in the rest of the East, and in the neighbouring countries'.[14]

Fars and Arabia

There were at least eight dioceses in Fars and the islands of the Persian Gulf in the 5th century, and probably eleven or more by the end of the Sassanian period. In Fars the diocese of Rev Ardashir is first mentioned in 420, the dioceses of Ardashir Khurrah (Shiraf), Darabgard, Istakhr, and Kazrun (Shapur or Bih Shapur) in 424, and a diocese of Qish in 540. On the Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf dioceses are first mentioned for Dairin and Mashmahig in 410 and for Beth Mazunaye (Oman) in 424. By 540 the bishop of Rev Ardashir had become a metropolitan, responsible for the dioceses of both Fars and Arabia. A fourth Arabian diocese, Hagar, is first mentioned in 576, and a fifth diocese, Hatta (previously part of the diocese of Hagar), is first mentioned in the acts of a regional synod held on the Persian Gulf island of Dairin in 676 by the patriarch Giwargis to determine the episcopal succession in Beth Qatraye, but may have been created before the Arab conquest.

Khorasan and Segestan

An East Syrian diocese for Abrashahr (Nishapur) evidently existed by the beginning of the 5th century, though it was not assigned to a metropolitan province in 410.[6] Three more East Syrian dioceses in Khorasan and Segestan are attested a few years later. The bishops Bar Shaba of Merv, David of Abrashahr, Yazdoï of Herat and Aphrid of Segestan were present at the synod of Dadishoʿ in 424.[15] The uncommon name of the bishop of Merv, Bar Shaba, means 'son of the deportation', suggesting that Merv's Christian community may have been deported from Roman territory.

The diocese of Segestan, whose bishop probably sat at Zarang, was disputed during the schism of Narsaï and Elishaʿ in the 520s. The patriarch Aba I resolved the dispute in 544 by temporarily dividing the diocese, assigning Zarang, Farah and Qash to the bishop Yazdaphrid and Bist and Rukut to the bishop Sargis. He ordered that the diocese should be reunited as soon as one of these bishops died.[16]

The Christian population of the Merv region seems to have increased during the 6th century, as the bishop of Merv was recognised as a metropolitan at the synod of Joseph in 554 and Herat also became a metropolitan diocese shortly afterwards. The first known metropolitan of Herat was present at the synod of Ishoʿyahb I in 585. The growing importance of the Merv region for the Church of the East is also attested by the appearance of several more Christian centres during the late 5th and 6th century. By the end of the 5th century the diocese of Abrashahr (Nishapur) also included the city of Tus, whose name featured in 497 in the title of the bishop Yohannis of 'Tus and Abrashahr'. Four more dioceses seem also to have been created in the 6th century. The bishops Yohannan of 'Abiward and Shahr Peroz' and Theodore of Merw-i Rud accepted the acts of the synod of Joseph in 554, the latter by letter, while the bishops Habib of Pusang and Gabriel of 'Badisi and Qadistan' adhered by proxy to the decisions of the synod of Ishoʿyahb I in 585, sending deacons to represent them.[17] None of these four dioceses is mentioned again, and it is not clear when they lapsed.

Media

By the end of the 5th century there were at least three East Syrian dioceses in the Sassanian province of Media in western Iran. Canon XXI of the synod of Isaac in 410 foreshadowed the extension of the metropolitan principle to the bishops of Beth Madaye and other relatively remote regions.[6] Hamadan (ancient Ecbatana) was the chief city of Media, and the Syriac name Beth Madaye (Media) was regularly used to refer to the East Syrian diocese of Hamadan as well as to the region as a whole. Although no East Syrian bishops of Beth Madaye are attested before 457, this reference probably indicates that the diocese of Hamadan was already in existence in 410. Bishops of Beth Madaye were present at most of the synods held between 486 and 605.[18] Two other dioceses in western Iran, Beth Lashpar (Hulwan) and Masabadan, seem also to have been established in the 5th century. A bishop of 'the deportation of Beth Lashpar' was present at the synod of Dadishoʿ in 424, and bishops of Beth Lashpar also attended the later synods of the 5th and 6th centuries.[19] Bishops of the nearby locality of Masabadan were present at the synod of Joseph in 554 and the synod of Ezekiel in 576.[20]

Rai and Tabaristan

In Tabaristan (northern Iran), the diocese of Rai (Beth Raziqaye) is first mentioned in 410, and seems to have had a fairly uninterrupted succession of bishops for the next six and a half centuries. Bishops of Rai are first attested in 424 and last mentioned towards the end of the 11th century.[21]

An East Syrian diocese was established in the Sassanian province of Gurgan (Hyrcania) to the southeast of the Caspian Sea in the 5th century for a community of Christians deported from Roman territory.[22] The bishop Domitian 'of the deportation of Gurgan', evidently from his name a Roman, was present at the synod of Dadishoʿ in 424, and three other 5th- and 6th-century bishops of Gurgan attended the later synods, the last of whom, Zaʿura, was among the signatories of the acts of the synod of Ezekiel in 576.[23] The bishops of Gurgan probably sat in the provincial capital Astarabad.[24]

Adarbaigan and Gilan

Bishops of the diocese of 'Adarbaigan' were present at most of the synods between 486 and 605. The diocese of Adarbaigan appears to have covered the territory included within the Sassanian province of Atropatene. It was bounded on the west by the Salmas and Urmi plains to the west of Lake Urmi and to the south by the diocese of Salakh in the province of Adiabene. Its centre seems to have been the town of Ganzak. The diocese of Adarbaigan was not assigned to a metropolitan province in 410, and may have remained independent throughout the Sassanian period. By the end of the 8th century, however, Adarbaigan was a suffragan diocese in the province of Adiabene.[25]

An East Syrian diocese for Paidangaran (modern Baylaqan) is attested during the 6th century, but only two of its bishops are known.[26] The bishop Yohannan of Paidangaran, first mentioned in 540, adhered to the acts of the synod of Mar Aba I in 544.[27] The bishop Yaʿqob of Paidangaran was present at the synod of Joseph in 544.[28]

The bishop Surin of 'Amol and Gilan' was present at the synod of Joseph in 554.[29]

Umayyad and Abbasid periods

A good starting point for a discussion of the diocesan organisation of the Church of the East after the Arab conquest is a list of fifteen contemporary East Syrian 'eparchies' or ecclesiastical provinces compiled in 893 by the metropolitan Eliya of Damascus. The list (in Arabic) included the province of the patriarch and fourteen metropolitan provinces: Jundishabur (Beth Huzaye), Nisibin (Nisibis), al-Basra (Maishan), al-Mawsil (Mosul), Bajarmi (Beth Garmaï), al-Sham (Damascus), al-Ray (Rai), Hara (Herat), Maru (Merv), Armenia, Qand (Samarqand), Fars, Bardaʿa and Hulwan.[4]

An important source for the ecclesiastical organisation of the Church of the East in the 12th century is a collection of canons, attributed to the patriarch Eliya III (1176–90), for the consecration of bishops, metropolitans and patriarchs. Included in the canons is what appears to be a contemporary list of twenty-five East Syrian dioceses, in the following order: (a) Nisibis; (b) Mardin; (c) Amid and Maiperqat; (d) Singara; (e) Beth Zabdaï; (f) Erbil; (g) Beth Waziq; (h) Athor [Mosul]; (i) Balad; (j) Marga; (k) Kfar Zamre; (l) Fars and Kirman; (m) Hindaye and Qatraye (India and northern Arabia); (n) Arzun and Beth Dlish (Bidlis); (o) Hamadan; (p) Halah; (q) Urmi; (r) Halat, Van and Wastan; (s) Najran; (t) Kashkar; (u) Shenna d'Beth Ramman; (v) Nevaketh; (w) Soqotra; (x) Pushtadar; and (y) the Islands of the Sea.[30]

There are some obvious omissions from this list, notably a number of dioceses in the province of Mosul, but it is probably legitimate to conclude that all the dioceses mentioned in the list were still in existence in the last quarter of the 12th century. If so, the list has some interesting surprises, such as the survival of dioceses for Fars and Kirman and for Najran at this late date. The mention of the diocese of Kfar Zamre near Balad, attested only once before, in 790, is another surprise, as is the mention of a diocese for Pushtadar in Persia. However, there is no need to doubt the authenticity of the list. Its mention of dioceses for Nevaketh and the Islands of the Sea have a convincing topicality.

Interior provinces

Province of the Patriarch

According to Eliya of Damascus, there were thirteen dioceses in the province of the patriarch in 893: Kashkar, al-Tirhan, Dair Hazql (an alternative name for al-Nuʿmaniya, the chief town in the diocese of Zabe), al-Hira (Hirta), al-Anbar (Piroz Shabur), al-Sin (Shenna d’Beth Ramman), ʿUkbara, al-Radhan, Nifr, al-Qasra, 'Ba Daraya and Ba Kusaya' (Beth Daraye), ʿAbdasi (Nahargur), and al-Buwazikh (Konishabur or Beth Waziq). Eight of these dioceses already existed in the Sassanian period, but the diocese of Beth Waziq is first mentioned in the second half of the 7th century, and the dioceses of ʿUkbara, al-Radhan, Nifr, and al-Qasra were probably founded in the 9th century. The first bishop of ʿUkbara whose name has been recorded, Hakima, was consecrated by the patriarch Sargis around 870, and bishops of al-Qasra, al-Radhan and Nifr are first mentioned in the 10th century. A bishop of 'al-Qasr and Nahrawan' became patriarch in 963, and then consecrated bishops for al-Radhan and for 'Nifr and al-Nil'. Eliya's list helps to confirm the impression given by the literary sources, that the East Syrian communities in Beth Aramaye were at their most prosperous in the 10th century.

A partial list of bishops present at the consecration of the patriarch Yohannan IV in 900 included several bishops from the province of the patriarch, including the bishops of Zabe and Beth Daraye and also the bishops Ishoʿzkha of 'the Gubeans', Hnanishoʿ of Delasar, Quriaqos of Meskene and Yohannan 'of the Jews'. The last four dioceses are not mentioned elsewhere and cannot be satisfactorily localised.[3]

In the 11th century decline began to set in. The diocese of Hirta (al-Hira) came to an end, and four other dioceses were combined into two: Nifr and al-Nil with Zabe (al-Zawabi and al-Nuʿmaniya), and Beth Waziq (al-Buwazikh) with Shenna d'Beth Ramman (al-Sin). Three more dioceses ceased to exist in the 12th century. The dioceses of Piroz Shabur (al-Anbar) and Qasr and Nahrawan are last mentioned in 1111, and the senior diocese of Kashkar in 1176. By the patriarchal election of 1222 the guardianship of the vacant patriarchal throne, the traditional privilege of the bishop of Kashkar, had passed to the metropolitans of ʿIlam. The trend of decline continued in the 13th century. The diocese of Zabe and Nil is last mentioned during the reign of Yahballaha II (1190–1222), and the diocese of ʿUkbara in 1222. Only three dioceses are known to have been still in existence at the end of the 13th century: Beth Waziq and Shenna, Beth Daron (Ba Daron), and (perhaps due to its sheltered position between the Tigris and the Jabal Hamrin) Tirhan. However, East Syrian communities may also have persisted in districts which no longer had bishops: a manuscript of 1276 was copied by a monk named Giwargis at the monastery of Mar Yonan 'on the Euphrates, near Piroz Shabur which is Anbar', nearly a century and a half after the last mention of a bishop of Anbar.[31]

Province of Elam

Of the seven suffragan dioceses attested in the province of Beth Huzaye in 576, only four were still in existence at the end of the 9th century. The diocese of Ram Hormizd seems to have lapsed, and the dioceses of Karka d'Ledan and Mihrganqadaq had been combined with the dioceses of Susa and Ispahan respectively. In 893 Eliya of Damascus listed four suffragan dioceses in the 'eparchy of Jundishapur', in the following order: Karkh Ladan and al-Sus (Susa and Karha d'Ledan), al-Ahwaz (Hormizd Ardashir), Tesr (Shushter) and Mihrganqadaq (Ispahan and Mihraganqadaq).[4] It is doubtful whether any of these dioceses survived into the 14th century. The diocese of Shushter is last mentioned in 1007/8, Hormizd Ardashir in 1012, Ispahan in 1111 and Susa in 1281. Only the metropolitan diocese of Jundishapur certainly survived into the 14th century, and with additional prestige. ʿIlam had for centuries ranked first among the metropolitan provinces of the Church of the East, and its metropolitan enjoyed the privilege of consecrating a new patriarch and sitting on his right hand at synods. By 1222, in consequence of the demise of the diocese of Kashkar in the province of the patriarch, he had also acquired the privilege of guarding the vacant patriarchal throne.

The East Syrian author ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis, writing around the end of the 13th century, mentions the bishop Gabriel of Shahpur Khwast (modern Hurremabad), who perhaps flourished during the 10th century. From its geographical location, Shahpur Khwast might have been a diocese in the province of ʿIlam, but it is not mentioned in any other source.[32]

Province of Nisibis

The metropolitan province of Nisibis had a number of suffragan dioceses at different periods, including the dioceses of Arzun, Beth Rahimaï, Beth Qardu (later renamed Tamanon), Beth Zabdaï, Qube d’Arzun, Balad, Shigar (Sinjar), Armenia, Harran and Callinicus (Raqqa), Maiperqat (with Amid and Mardin), Reshʿaïna, and Qarta and Adarma.

Probably during the Ummayad period, the East Syrian diocese of Armenia was attached to the province of Nisibis. The bishop Artashahr of Armenia was present at the synod of Dadishoʿ in 424, but the diocese was not assigned to a metropolitan province. In the late 13th century Armenia was certainly a suffragan diocese of the province of Nisibis, and its dependency probably went back to the 7th or 8th century. The bishops of Armenia appear to have sat at the town of Halat (Ahlat) on the northern shore of Lake Van.

The Arab conquest allowed the East Syrians to move into western Mesopotamia and establish communities in Damascus and other towns that had formerly been in Roman territory, where they lived alongside much larger Syrian Orthodox, Armenian and Melkite communities. Some of these western communities were placed under the jurisdiction of the East Syrian metropolitans of Damascus, but others were attached to the province of Nisibis. The latter included a diocese for Harran and Callinicus (Raqqa), first attested in the 8th century and last mentioned towards the end of the 11th century, and a diocese at Maiperqat, first mentioned at the end of the 11th century, whose bishops were also responsible for the East Syrian communities in Amid and Mardin.[33] Lists of dioceses in the province of Nisibis during the 11th and 13th centuries also mention a diocese for the Syrian town of Reshʿaïna (Raʿs al-ʿAin). Reshʿaïna is a plausible location for an East Syrian diocese at this period, but none of its bishops are known.[34]

Province of Maishan

The province of Maishan seems to have come to an end in the 13th century. The metropolitan diocese of Prath d’Maishan is last mentioned in 1222, and the suffragan dioceses of Nahargur (ʿAbdasi), Karka d'Maishan (Dastumisan), and Rima (Nahr al-Dayr) probably ceased to exist rather earlier. The diocese of Nahargur is last mentioned at the end of the 9th century, in the list of Eliya of Damascus. The last-known bishop of Karka d'Maishan, Abraham, was present at the synod held by the patriarch Yohannan IV shortly after his election in 900, and an unnamed bishop of Rima attended the consecration of Eliya I in Baghdad in 1028.[35]

Provinces of Mosul and Erbil

Erbil, the chief town of Adiabene, lost much of its former importance with the growth of the city of Mosul, and during the reign of the patriarch Timothy I (780–823) the seat of the metropolitans of Adiabene was moved to Mosul. The dioceses of Adiabene were governed by a 'metropolitan of Mosul and Erbil' for the next four and a half centuries. Around 1200, Mosul and Erbil became separate metropolitan provinces. The last known metropolitan of Mosul and Erbil was Tittos, who was appointed by Eliya III (1175–89). Thereafter separate metropolitan bishops for Mosul and for Erbil are recorded in a fairly complete series from 1210 to 1318.

Five new dioceses in the province of Mosul and Erbil were established during the Ummayad and ʿAbbasid periods: Marga, Salakh, Haditha, Taimana and Hebton. The dioceses of Marga and Salakh, covering the districts around ʿAmadiya and ʿAqra, are first mentioned in the 8th century but may have been created earlier, perhaps in response to West Syrian competition in the Mosul region in the 7th century. The diocese of Marga persisted into the 14th century, but the diocese of Salakh is last mentioned in the 9th century. By the 8th century there was also an East Syrian diocese for the town of Hdatta (Haditha) on the Tigris, which persisted into the 14th century. The diocese of Taimana, which embraced the district south of the Tigris in the vicinity of Mosul and included the monastery of Mar Mikha'il, is attested between the 8th and 10th centuries, but does not seem to have persisted into the 13th century.[36]

A number of East Syrian bishops are attested between the 8th and 13th centuries for the diocese of Hebton, a region of northwest Adiabene to the south of the Great Zab, adjacent to the district of Marga. It is not clear when the diocese was created, but it is first mentioned under the name 'Hnitha and Hebton' in 790. Hnitha was another name for the diocese of Maʿaltha, and the patriarch Timothy I is said to have united the dioceses of Hebton and Ḥnitha in order to punish the presumption of the bishop Rustam of Hnitha, who had opposed his election. The union was not permanent, and by the 11th century Hebton and Maʿaltha were again separate dioceses.

By the middle of the 8th century the diocese of Adarbaigan, formerly independent, was a suffragan diocese of the province of Adiabene.[37]

Province of Beth Garmaï

In its heyday, at the end of the 6th century, there were at least nine dioceses in the province of Beth Garmaï. As in Beth Aramaye, the Christian population of Beth Garmaï began to fall in the first centuries of Moslem rule, and the province's decline is reflected in the forced relocation of the metropolis from Karka d'Beth Slokh (Kirkuk) in the 9th century and the gradual disappearance of all of the province's suffragan dioceses between the 7th and 12th centuries. The dioceses of Hrbath Glal and Barhis are last mentioned in 605; Mahoze d’Arewan around 650; Karka d’Beth Slokh around 830; Khanijar in 893; Lashom around 895; Tahal around 900; Shahrgard in 1019; and Shahrzur around 1134. By the beginning of the 14th century the metropolitan of Beth Garmaï, who now sat at Daquqa, was the only remaining bishop in this once-flourishing province.

Exterior provinces

Fars and Arabia

At the beginning of the 7th century there were several dioceses in the province of Fars and its dependencies in northern Arabia (Beth Qatraye). Fars was marked out by its Arab conquerors for a thoroughgoing process of islamicisation, and Christianity declined more rapidly in this region than in any other part of the former Sassanian empire. The last-known bishop of the metropolitan see of Rev Ardashir was ʿAbdishoʿ, who was present at the enthronement of the patriarch ʿAbdishoʿ III in 1138. In 890 Eliya of Damascus listed the suffragan sees of Fars, in order of seniority, as Shiraz, Istakhr, Shapur (probably to be identified with Bih Shapur, i.e. Kazrun), Karman, Darabgard, Shiraf (Ardashir Khurrah), Marmadit, and the island of Soqotra. Only two bishops are known from the mainland dioceses: Melek of Darabgard, who was deposed in the 560s, and Gabriel of Bih Shapur, who was present at the enthronement of ʿAbdishoʿ I in 963. Fars was spared by the Mongols for its timely submission in the 1220s, but by then there seem to have been few Christians left, although an East Syrian community (probably without bishops) survived at Hormuz. This community is last mentioned in the 16th century.

Of the northern Arabian dioceses, Mashmahig is last mentioned around 650, and Dairin, Oman (Beth Mazunaye), Hajar and Hatta in 676. Soqotra remained an isolated outpost of Christianity in the Arabian sea, and its bishop attended the enthronement of the patriarch Yahballaha III in 1281. Marco Polo visited the island in the 1280s, and claimed that it had an East Syrian archbishop, with a suffragan bishop on the nearby 'Island of Males'. In a casual testimony to the impressive geographical extension of the Church of the East in the ʿAbbasid period, Thomas of Marga mentions that Yemen and Sanaʿa had a bishop named Peter during the reign of the patriarch Abraham II (837–50) who had earlier served in China. This diocese is not mentioned again.

Khorasan and Segestan

Timothy I consecrated a metropolitan named Hnanishoʿ for Sarbaz in the 790s. This diocese is not mentioned again. In 893 Eliya of Damascus recorded that the metropolitan province of Merv had suffragan sees at 'Dair Hans', 'Damadut', and 'Daʿbar Sanai', three districts whose locations are entirely unknown.

By the 11th century East Syrian Christianity was in decline in Khorasan and Segestan. The last-known metropolitan of Merv was ʿAbdishoʿ, who was consecrated by the patriarch Mari (987–1000). The last-known metropolitan of Herat was Giwargis, who flourished in the reign of Sabrishoʿ III (1064–72). If any of the suffragan dioceses were still in existence at this period, they are not mentioned. The surviving urban Christian communities in Khorasan suffered a heavy blow at the start of the 13th century, when the cities of Merv, Nishapur and Herat were stormed by Genghis Khan in 1220. Their inhabitants were massacred, and although all three cities were refounded shortly afterwards, it is likely that they had only small East Syrian communities thereafter. Nevertheless, at least one diocese survived into the 13th century. In 1279 an unnamed bishop of Tus entertained the monks Bar Sawma and Marqos in the monastery of Mar Sehyon near Tus during their pilgrimage from China to Jerusalem.

Media

In 893 Eliya of Damascus listed Hulwan as a metropolitan province, with suffragan dioceses for Dinawar (al-Dinur), Hamadan, Nihawand and al-Kuj.[4] 'Al-Kuj' cannot be readily localised, and has been tentatively identified with Karaj d'Abu Dulaf.[38] Little is known about these suffragan dioceses, except for isolated references to bishops of Dinawar and Nihawand, and by the end of the 12th century Hulwan and Hamadan were probably the only surviving centres of East Syrian Christianity in Media. Around the beginning of the 13th century the metropolitan see of Hulwan was transferred to Hamadan, in consequence of the decline in Hulwan's importance. The last-known bishop of Hulwan and Hamadan, Yohannan, flourished during the reign of Eliya III (1176–90). Hamadan was sacked in 1220, and during the reign of Yahballaha III was also on more than one occasion the scene of anti-Christian riots. It is possible that its Christian population at the end of the 13th century was small indeed, and it is not known whether it was still the seat of a metropolitan bishop.

Rai and Tabaristan

The diocese of Rai was raised to metropolitan status in 790 by the patriarch Timothy I. According to Eliya of Damascus, Gurgan was a suffragan diocese of the province of Rai in 893. It is doubtful whether either diocese still existed at the end of the 13th century. The last-known bishop of Rai, ʿAbd al-Masih, was present at the consecration of ʿAbdishoʿ II in 1075 as 'metropolitan of Hulwan and Rai', suggesting that the episcopal seat of the bishops of Rai had been transferred to Hulwan. According to the Mukhtasar of 1007/08, the diocese of 'Gurgan, Bilad al-Jibal and Dailam' had been suppressed, 'owing to the disappearance of Christianity in the region'.[39]

Little Armenia

The Arran or Little Armenia district in modern Azerbaijan, with its chief town Bardaʿa, was an East Syrian metropolitan province in the 10th and 11th centuries, and represented the northernmost extension of the Church of the East.[40] A manuscript note of 1137 mentions that the diocese of Bardaʿa and Armenia no longer existed, and that the responsibilities of its metropolitans had been undertaken by the bishop of Halat.

Dailam, Gilan and Muqan

A major missionary drive was undertaken by the Church of the East in Dailam and Gilan towards the end of the 8th century on the initiative of the patriarch Timothy I (780–823), led by three metropolitans and several suffragan bishops from the monastery of Beth ʿAbe. Thomas of Marga, who gave a detailed account of this mission in the Book of Governors, preserved the names of the East Syrian bishops sent to Dailam:

Mar Qardagh, Mar Shubhalishoʿ and Mar Yahballaha were elected metropolitans of Gilan and of Dailam; and Thomas of Hdod, Zakkai of Beth Mule, Shem Bar Arlaye, Ephrem, Shemʿon, Hnanya and David, who went with them from this monastery, were elected and consecrated bishops of those countries.[41]

The metropolitan province of Dailam and Gilan created by Timothy I was transitory. Moslem missionaries began to convert the Dailam region to Islam in the 9th century, and by the beginning of the 11th century the East Syrian diocese of Dailam, by then united with Gurgan as a suffragan diocese of Rai, no longer existed.[42]

Timothy I also consecrated a bishop named Eliya for the Caspian district of Muqan, a diocese not mentioned elsewhere and probably also short-lived.[43]

Turkestan

In Central Asia, the patriarch Sliba-zkha (714–28) created a metropolitan province for Samarqand, and a metropolitan of Samarqand is attested in 1018.[44] Samarqand surrendered to Genghis Khan in 1220, and although many of its citizens were killed, the city was not destroyed. Marco Polo mentions an East Syrian community in Samarqand in the 1270s. Timothy I (780–823) consecrated a metropolitan for Beth Turkaye, 'the country of the Turks'. Beth Turkaye has been distinguished from Samarqand by the French scholar Dauvillier, who noted that ʿAmr listed the two provinces separately, but may well have been another name for the same province. Eliya III (1176–90) created a metropolitan province for Kashgar and Nevaketh.[45]

India

India, which boasted a substantion East Syrian community at least as early as the 3rd century (the Saint Thomas Christians), became a metropolitan province of the Church of the East in the 7th century. Although few references to its clergy have survived, the colophon of a manuscript copied in 1301 in the church of Mar Quriaqos in Cranganore mentions the metropolitan Yaʿqob of India. The metropolitan seat for India at this period was probably Cranganore, described in this manuscript as 'the royal city', and the main strength of the East Syrian church in India was along the Malabar Coast, where it was when the Portuguese arrived in India at the beginning of the 16th century. There were also East Syrian communities on the east coast, around Madras and the shrine of Saint Thomas at Meliapur.

Islands of the Sea

An East Syrian metropolitan province in the "Islands of the Sea" existed at some point between the 11th and 14th centuries; this may be a reference to the East Indies. The patriarch Sabrishoʿ III (1064–72) despatched the metropolitan Hnanishoʿ of Jerusalem on a visitation to 'the Islands of the Sea'.[46] These 'Islands of the Sea' may well have been the East Indies, as a list of metropolitan provinces compiled by the East Syrian writer ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis at the beginning of the 14th century includes the province 'of the Islands of the Sea between Dabag, Sin and Masin'. Sin and Masin appear to refer to northern and southern China respectively, and Dabag to Java, implying that the province covered at least some of the islands of the East Indies. The memory of this province persisted into the 16th century. In 1503 the patriarch Eliya V, in response to the request of a delegation from the East Syrian Christians of Malabar, also consecrated a number of bishops 'for India and the Islands of the Sea between Dabag, Sin and Masin'.[47]

China and Tibet

The Church of the East is perhaps best known nowadays for its missionary work in China during the Tang Dynasty. The first recorded Christian mission to China was led by a Nestorian Christian with the Chinese name Alopen, who arrived in the Chinese capital Chang'an in 635.[48] In 781 a tablet (commonly known as the Nestorian Stele) was erected in the grounds of a Christian monastery in the Chinese capital Chang'an by the city's Christian community, displaying a long inscription in Chinese with occasional glosses in Syriac. The inscription described the eventful progress of the Nestorian mission in China since Alopen's arrival.

China became a metropolitan province of the Church of the East, under the name Beth Sinaye, in the first quarter of the 8th century. According to the 14th-century writer ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis, the province was established by the patriarch Sliba-zkha (714–28).[49] Arguing from its position in the list of exterior provinces, which implied an 8th-century foundation, and on grounds of general historical probability, ʿAbdishoʿ refuted alternative claims that the province of Beth Sinaye had been founded either by the 5th-century patriarch Ahha (410–14) or the 6th-century patriarch Shila (503–23).[50]

The Nestorian Stele inscription was composed in 781 by Adam, 'priest, bishop and papash of Sinistan', probably the metropolitan of Beth Sinaye, and the inscription also mentions the archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan [Chang'an] and Gabriel of Sarag [Lo-yang]; Yazdbuzid, 'priest and country-bishop of Khumdan'; Sargis, 'priest and country-bishop'; and the bishop Yohannan. These references confirm that the Church of the East in China had a well-developed hierarchy at the end of the 8th century, with bishops in both northern capitals, and there were probably other dioceses besides Chang'an and Lo-yang. Shortly afterwards Thomas of Marga mentions the monk David of Beth ʿAbe, who was metropolitan of Beth Sinaye during the reign of Timothy I (780–823). Timothy I is said also to have consecrated a metropolitan for Tibet (Beth Tuptaye), a province not again mentioned. The province of Beth Sinaye is last mentioned in 987 by the Arab writer Abu'l Faraj, who met a Nestorian monk who had recently returned from China, who informed him that 'Christianity was just extinct in China; the native Christians had perished in one way or another; the church which they had used had been destroyed; and there was only one Christian left in the land'.[51]

Syria, Palestine, Cilicia and Egypt

Although the main East Syrian missionary impetus was eastwards, the Arab conquests paved the way for the establishment of East Syrian communities to the west of the Church's northern Mesopotamian heartland, in Syria, Palestine, Cilicia and Egypt. Damascus became the seat of an East Syrian metropolitan around the end of the 8th century, and the province had five suffragan dioceses in 893: Aleppo, Jerusalem, Mambeg, Mopsuestia, and Tarsus and Malatya.[4]

According to Thomas of Marga, the diocese of Damascus was established in the 7th century as a suffragan diocese in the province of Nisibis. The earliest known bishop of Damascus, Yohannan, is attested in 630. His title was 'bishop of the scattered of Damascus', presumably a population of East Syrian refugees displaced by the Roman-Persian Wars. Damascus was raised to metropolitan status by the patriarch Timothy I (780–823). In 790 the bishop Shallita of Damascus was still a suffragan bishop.[52] Some time after 790 Timothy consecrated the future patriarch Sabrishoʿ II (831–5) as the city's first metropolitan.[53] Several metropolitans of Damascus are attested between the 9th and 11th centuries, including Eliya Ibn ʿUbaid, who was consecrated in 893 by the patriarch Yohannan III and bore the title 'metropolitan of Damascus, Jerusalem and the Shore (probably a reference to the East Syrian communities in Cilicia)'.[54] The last known metropolitan of Damascus, Marqos, was consecrated during the reign of the patriarch ʿAbdishoʿ II (1074–90).[55] It is not clear whether the diocese of Damascus survived into the 12th century.

Although little is known about its episcopal succession, the East Syrian diocese of Jerusalem seems to have remained a suffragan diocese in the province of Damascus throughout the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries.[56] The earliest known bishop of Jerusalem was Eliya Ibn ʿUbaid, who was appointed metropolitan of Damascus in 893 by the patriarch Yohannan III.[54] Nearly two centuries later a bishop named Hnanishoʿ was consecrated for Jerusalem by the patriarch Sabrishoʿ III (1064–72).[46]

Little is known about the diocese of Aleppo, and even less about the dioceses of Mambeg, Mopsuestia, and Tarsus and Malatya. The literary sources have preserved the name of only one bishop from these regions, Ibn Tubah, who was consecrated for Aleppo by the patriarch Sabrishoʿ III in 1064.[46]

A number of East Syrian bishops of Egypt are attested between the 8th and 11th centuries. The earliest known bishop, Yohannan, is attested around the beginning of the 8th century. His successors included Sulaiman, consecrated in error by the patriarch ʿAbdishoʿ I (983–6) and recalled when it was discovered that the diocese already had a bishop; Joseph al-Shirazi, injured during a riot in 996 in which Christian churches in Egypt were attacked; Yohannan of Haditha, consecrated by the patriarch Sabrishoʿ III in 1064; and Marqos, present at the consecration of the patriarch Makkikha I in 1092. It is doubtful whether the East Syrian diocese of Egypt survived into the 13th century.[57]

Mongol period

At the end of the 13th century the Church of the East still extended across Asia to China. Twenty-two bishops were present at the consecration of Yahballaha III in 1281, and while most of them were from the dioceses of northern Mesopotamia, the metropolitans of Jerusalem, ʿIlam, and Tangut (northwest China), and the bishops of Susa and the island of Soqotra were also present. During their journey from China to Baghdad in 1279, Yahballaha and Bar Sawma were offered hospitality by an unnamed bishop of Tus in northeastern Persia, confirming that there was still a Christian community in Khorasan, however reduced. India had a metropolitan named Yaʿqob at the beginning of the 14th century, mentioned together with the patriarch Yahballaha 'the fifth (sic), the Turk' in a colophon of 1301. In the 1320s Yahballaha's biographer praised the progress made by the Church of the East in converting the 'Indians, Chinese and Turks', without suggesting that this achievement was under threat.[58] In 1348 ʿAmr listed twenty-seven metropolitan provinces stretching from Jerusalem to China, and although his list may be anachronistic in several respects, he was surely accurate in portraying a church whose horizons still stretched far beyond Kurdistan. The provincial structure of the church in 1318 was much the same as it had been when it was established in 410 at the synod of Isaac, and many of the 14th-century dioceses had existed, though perhaps under a different name, nine hundred years earlier.

Interior provinces

At the same time, however, significant changes had taken place which were only partially reflected in the organisational structure of the church. Between the 7th and 14th centuries Christianity gradually disappeared in southern and central Iraq (the ecclesiastical provinces of Maishan, Beth Aramaye and Beth Garmaï). There were twelve dioceses in the patriarchal province of Beth Aramaye at the beginning of the 11th century, only three of which (Beth Waziq, Beth Daron, and Tirhan, all well to the north of Baghdad) survived into the 14th century.[59] There were four dioceses in Maishan (the Basra district) at the end of the 9th century, only one of which (the metropolitan diocese of Prath d’Maishan) survived into the 13th century, to be mentioned for the last time in 1222.[35] There were at least nine dioceses in the province of Beth Garmaï in the 7th century, only one of which (the metropolitan diocese of Daquqa) survived into the 14th century.[60] The disappearance of these dioceses was a slow and apparently peaceful process (which can be traced in some detail in Beth Aramaye, where dioceses were repeatedly amalgamated over a period of two centuries), and it is probable that the consolidation of Islam in these districts was accompanied by a gradual migration of East Syrian Christians to northern Iraq, whose Christian population was larger and more deeply rooted, not only in the towns but in hundreds of long-established Christian villages.

By the end of the 13th century, although isolated East Syrian outposts persisted to the southeast of the Great Zab, the districts of northern Mesopotamia included in the metropolitan provinces of Mosul and Nisibis were clearly regarded as the heartland of the Church of the East. When the monks Bar Sawma and Marqos (the future patriarch Yahballaha III) arrived in Mesopotamia from China in the late 1270s, they visited several East Syrian monasteries and churches:

They arrived in Baghdad, and from there they went to the great church of Kokhe, and to the monastery of Mar Mari the apostle, and received a blessing from the relics of that country. And from there they turned back and came to the country of Beth Garmaï, and they received blessings from the shrine of Mar Ezekiel, which was full of helps and healings. And from there they went to Erbil, and from there to Mosul. And they went to Shigar, and Nisibis and Mardin, and were blessed by the shrine containing the bones of Mar Awgin, the second Christ. And from there they went to Gazarta d'Beth Zabdaï, and they were blessed by all the shrines and monasteries, and the religious houses, and the monks, and the fathers in their dioceses.[61]

With the exception of the patriarchal church of Kokhe in Baghdad and the nearby monastery of Mar Mari, all these sites were well to the north of Baghdad, in the districts of northern Mesopotamia where historic East Syrian Christianity survived into the 20th century.

A similar pattern is evident several years later. Eleven bishops were present at the consecration of the patriarch Timothy II in 1318: the metropolitans Joseph of ʿIlam, ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis and Shemʿon of Mosul, and the bishops Shemʿon of Beth Garmaï, Shemʿon of Tirhan, Shemʿon of Balad, Yohannan of Beth Waziq, Yohannan of Shigar, ʿAbdishoʿ of Hnitha, Isaac of Beth Daron and Ishoʿyahb of Tella and Barbelli (Marga). Timothy himself had been metropolitan of Erbil before his election as patriarch. Again, with the exception of ʿIlam (whose metropolitan, Joseph, was present in his capacity of 'guardian of the throne' (natar kursya) all the dioceses represented were in northern Mesopotamia.[62]

Provinces of Mosul and Erbil

At the beginning of the 13th century there were at least eight suffragan dioceses in the provinces of Mosul and Erbil: Haditha, Maʿaltha, Hebton, Beth Bgash, Dasen, Beth Nuhadra, Marga and Urmi. The diocese of Hebton is last mentioned in 1257, when its bishop Gabriel attended the consecration of the patriarch Makkikha II.[63] The diocese of Dasen definitely persisted into the 14th century, as did the diocese of Marga, though it was renamed Tella and Barbelli in the second half of the 13th century. It is possible that the dioceses of Beth Nuhadra, Beth Bgash and Haditha also survived into the 14th century. Haditha, indeed, is mentioned as a diocese at the beginning of the 14th century by ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis.[64] Urmi too, although none of its bishops are known, may also have persisted as a diocese into the 16th century, when it again appears as the seat of an East Syrian bishop.[65] The diocese of Maʿaltha is last mentioned in 1281, but probably persisted into the 14th century under the name Hnitha. The bishop ʿAbdishoʿ 'of Hnitha', attested in 1310 and 1318, was almost certainly a bishop of the diocese formerly known as Maʿaltha.[66]

Province of Nisibis

The celebrated East Syrian writer ʿAbdishoʿ of Nisibis, himself metropolitan of Nisibis and Armenia, listed thirteen suffragan dioceses in the province 'of Soba (Nisibis) and Mediterranean Syria' at the end of the 13th century, in the following order: Arzun, Qube, Beth Rahimaï, Balad, Shigar, Qardu, Tamanon, Beth Zabdaï, Halat, Harran, Amid, Reshʿaïna and 'Adormiah' (Qarta and Adarma).[67] It has been convincingly argued that ʿAbdishoʿ was giving a conspectus of dioceses in the province of Nisibis at various periods in its history rather than an authentic list of late 13th-century dioceses, and it is most unlikely that dioceses of Qube, Beth Rahimaï, Harran and Reshʿaïna still existed at this period.

A diocese was founded around the middle of the 13th century to the north of the Tur ʿAbdin for the town of Hesna d'Kifa, perhaps in response to East Syrian immigration to the towns of the Tigris plain during the Mongol period. At the same time, a number of older dioceses may have ceased to exist. The dioceses of Qaimar and Qarta and Adarma are last mentioned towards the end of the 12th century, and the diocese of Tamanon in 1265, and it is not clear whether they persisted into the 14th century. The only dioceses in the province of Nisibis definitely in existence at the end of the 13th century were Armenia (whose bishops sat at Halat on the northern shore of Lake Van), Shigar, Balad, Arzun and Maiperqat.

Exterior provinces

Arabia, Persia and Central Asia

By the end of the 13th century Christianity was also declining in the exterior provinces. Between the 7th and 14th centuries Christianity gradually disappeared in Arabia and Persia. There were at least five dioceses in northern Arabia in the 7th century and nine in Fars at the end of the 9th century, only one of which (the isolated island of Soqotra) survived into the 14th century.[68] There were perhaps twenty East Syrian dioceses in Media, Tabaristan, Khorasan and Segestan at the end of the 9th century, only one of which (Tus in Khorasan) survived into the 13th century.[69]

The East Syrian communities in Central Asia disappeared during the 14th century. Continual warfare eventually made it impossible for the Church of the East to send bishops to minister to its far-flung congregations. The blame for the destruction of the Christian communities east of Iraq has often been thrown upon the Turco-Mongol leader Timur, whose campaigns during the 1390s spread havoc throughout Persia and Central Asia. There is no reason to doubt that Timur was responsible for the destruction of certain Christian communities, but in much of central Asia Christianity had died out decades earlier. The surviving evidence, including a large number of dated graves, indicates that the crisis for the Church of the East occurred in the 1340s rather than the 1390s. Few Christian graves have been found later than the 1340s, indicating that the isolated East Syrian communities in Central Asia, weakened by warfare, plague and lack of leadership, converted to Islam around the middle of the 14th century.

Adarbaigan

Although the Church of the East was losing ground to Islam in Iran and Central Asia, it was making gains elsewhere. The migration of Christians from southern Mesopotamia led to a revival of Christianity in the province of Adarbaigan, where Christians could practice their religion freely under Mongol protection. An East Syrian diocese is mentioned as early as 1074 at Urmi,[65] and three others were created before the end of the 13th century, one a new metropolitan see for the province of Adarbaigan (possibly replacing the old metropolitan province of Arran, and with its seat at Tabriz), and three others for Eshnuq, Salmas and al-Rustaq (probably to be identified with the Shemsdin district of Hakkari).[70] The metropolitan of Adarbaigan was present at the consecration of the patriarch Denha I in 1265, while bishops of Eshnuq, Salmas and al-Rustaq attended the consecration of Yahballaha III in 1281. The foundation of these four dioceses probably reflected a migration of East Syrian Christians to the shores of Lake Urmi after the lakeside towns became Mongol cantonments in the 1240s. According to the Armenian historian Kirakos of Gandzak, the Mongol occupation of Adarbaigan enabled churches to be built in Tabriz and Nakichevan for the first time in those cities’ history. Substantial Christian communities are attested in both towns at the end of the 13th century, and also in Maragha, Hamadan and Sultaniyyeh.

China

There were also temporary Christian gains further afield. The Mongol conquest of China in the second half of the 13th century allowed the East Syrian church to return to China, and by the end of the century two new metropolitan provinces had been created for China, Tangut and 'Katai and Ong'.[71]

The province of Tangut covered northwestern China, and its metropolitan seems to have sat at Almaliq. The province evidently had several dioceses, even though they cannot now be localised, as the metropolitan Shemʿon Bar Qaligh of Tangut was arrested by the patriarch Denha I shortly before his death in 1281 'together with a number of his bishops'.[72]

The province of Katai [Cathay] and Ong, which seems to have replaced the old T'ang dynasty province of Beth Sinaye, covered northern China and the country of the Christian Ongut tribe around the great bend of the Yellow River. The metropolitans of Katai and Ong probably sat at the Mongol capital Khanbaliq. The patriarch Yahballaha III grew up in a monastery in northern China in the 1270s, and the metropolitans Giwargis and Nestoris are mentioned in his biography.[73] Yahballaha himself was consecrated metropolitan of Katai and Ong by the patriarch Denha I shortly before his death in 1281.[74]

During the first half of the 14th century there were East Syrian Christian communities in many cities in China, and the province of Katai and Ong probably had several suffragan dioceses. In 1253 William of Rubruck mentioned a Nestorian bishop in the town of 'Segin' (Xijing, modern Datong in Shanxi province). The tomb of a Nestorian bishop named Shlemun, who died in 1313, has recently been discovered at Quanzhou in Fujian province. Shlemun's epitaph described him as 'administrator of the Christians and Manicheans of Manzi (south China)'. Marco Polo had earlier reported the existence of a Manichean community in Fujian, at first thought to be Christian, and it is not surprising to find this small religious minority represented officially by a Christian bishop.[75]

The 14th-century Nestorian communities in China existed under Mongol protection, and were dispersed when the Mongol Yuan dynasty was overthrown in 1368.

Palestine and Cyprus

There were East Syrian communities at Antioch, Tripolis and Acre in the 1240s. The metropolitan Abraham 'of Jerusalem and Tripolis' was present at the consecration of the patriarch Yaballaha III in 1281.[76] Abraham probably sat in the coastal city of Tripolis (still in Crusader hands until 1289) rather than Jerusalem, which had fallen definitively to the Mameluks in 1241.

The Crusader stronghold of Acre, the last city in the Holy Land under Christian control, fell to the Mameluks in 1291. Most of the city's Christians, unwilling to live under Moslem rule, abandoned their homes and resettled in Christian Cyprus. Cyprus had an East Syrian bishop in 1445, Timothy, who made a Catholic profession of faith at the Council of Florence, and was probably already the seat of an East Syrian bishop or metropolitan by the end of the 13th century.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Chabot, 274–5, 283–4, 285, 306–7 and 318–51

- ↑ Chabot, 318–51, 482 and 608

- 1 2 MS Paris BN Syr 354, folio 147

- 1 2 3 4 5 Assemani, BO, ii. 485–9

- ↑ Wallis Budge, Book of Governors, ii. 444–9

- 1 2 3 4 Chabot, 273

- ↑ Chabot, 272

- 1 2 3 4 Chabot, 272–3

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 57–8

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 134

- ↑ Chabot, 272–3; Fiey, POCN, 59–60, 100, 114 and 125–6

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 106 and 115–16

- ↑ Chabot, 285, 344–5, 368 and 479

- ↑ Chabot, 320–1

- ↑ Chabot, 285

- ↑ Chabot, 339-45

- ↑ Chabot, 366 and 423

- ↑ Chabot, 306, 316, 366 and 479

- ↑ Chabot, 285, 287, 307, 315, 366, 368, 423 and 479

- ↑ Chabot, 366 and 368

- ↑ Fiey, Médie chrétienne, 378–82; POCN, 124

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 85–6

- ↑ Chabot, 285, 315, 328 and 368

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 85–6

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 81–2

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 119

- ↑ Chabot, 328 and 344–5

- ↑ Chabot, 366

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 82–3

- ↑ MS Cambridge Add. 1988

- ↑ MS Harvard Syr 27

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 131

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 49–50 and 88

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 124

- 1 2 Fiey, AC, iii. 272–82

- ↑ Fiey, AC, ii. 336–7; and POCN, 137

- ↑ Wallis Budge, Book of Governors, ii. 315–16

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 99

- ↑ Fiey POCN, 86

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 58–9

- ↑ Wallis Budge, Book of Governors, ii. 447–8

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 82–3

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 113

- ↑ Eliya of Nisibis, Chronography (ed. Brooks), i. 35

- ↑ Dauvillier, Provinces chaldéennes, 283–91; Fiey, POCN, 128

- 1 2 3 Mari, 125 (Arabic), 110 (Latin)

- ↑ Dauvillier, Provinces chaldéennes, 314–16

- ↑ Moule, Christians in China before the Year 1550, 38

- ↑ Mai, Scriptorum Veterum Nova Collectio, x. 141

- ↑ Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church, 123–4

- ↑ Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church, 222

- ↑ Chabot, 608.

- ↑ Mari, 76 (Arabic), 67–8 (Latin)

- 1 2 Sliba, 80 (Arabic)

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 72

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 97–8

- ↑ Meinardus, 116–21; Fiey, POCN, 78

- ↑ Wallis Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, 122–3

- ↑ Fiey, AC, iii. 151–262

- ↑ Fiey, AC, iii. 54–146

- ↑ Wallis Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, 142–3

- ↑ Assemani, BO, iii. i. 567–80

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 89–90

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 86–7

- 1 2 Fiey, POCN, 141–2

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 91–2 and 106

- ↑ Chabot, 619–20

- ↑ Fiey, Communautés syriaques, 177–219

- ↑ Fiey, Communautés syriaques, 75–104 and 357–84

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 126, 127 and 142–3

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 48–9, 103–4 and 137–8

- ↑ Bar Hebraeus, Ecclesiastical Chronicle, ii. 450

- ↑ Wallis Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, 127 and 132

- ↑ Bar Hebraeus, Ecclesiastical Chronicle, ii. 452

- ↑ Lieu, S., Manichaeism in Central Asia and China, 180

- ↑ Sliba, 124 (Arabic)

References

- Abbeloos, J. B., and Lamy, T. J., Bar Hebraeus, Chronicon Ecclesiasticum (3 vols, Paris, 1877)

- Assemani, J. A., De Catholicis seu Patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum (Rome, 1775)

- Assemani, J. S., Bibliotheca Orientalis Clementino-Vaticana (4 vols, Rome, 1719–28)

- Brooks, E. W., Eliae Metropolitae Nisibeni Opus Chronologicum (Rome, 1910)

- Chabot, J. B., Synodicon Orientale (Paris, 1902)

- Dauvillier, J., 'Les provinces chaldéennes "de l'extérieur" au Moyen Âge', in Mélanges Cavallera (Toulouse, 1948), reprinted in Histoire et institutions des Églises orientales au Moyen Âge (Variorum Reprints, London, 1983)

- Fiey, J. M., Assyrie chrétienne (3 vols, Beirut, 1962)

- Fiey, J. M., Communautés syriaques en Iran et en Irak, des origines à 1552 (London, 1979)

- Fiey, J. M., 'L'Élam, La Première des Métropoles Ecclésiastiques Syriennes Orientales', Parole de l'Orient, 1 (1970), 123–53

- Fiey, J. M., Nisibe, métropole syriaque orientale et ses suffragants, des origines à nos jours (Louvain, 1977)

- Fiey, J. M., Pour un Oriens Christianus novus; répertoire des diocèses Syriaques orientaux et occidentaux (Beirut, 1993)

- Gismondi, H., Maris, Amri, et Salibae: De Patriarchis Nestorianorum Commentaria I: Amri et Salibae Textus (Rome, 1896)

- Gismondi, H., Maris, Amri, et Salibae: De Patriarchis Nestorianorum Commentaria II: Maris textus arabicus et versio Latina (Rome, 1899)

- Meinardus, O., 'The Nestorians in Egypt', Oriens Christianus, 51 (1967), 116–21

- Moule, Arthur C., Christians in China before the year 1550, London, 1930

- Tfinkdji, J., 'L’église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd’hui', Annuaire Pontifical Catholique, 17 (1914), 449–525

- Tisserant, E., 'Église nestorienne', Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, 11, cols. 157–323

- Wallis Budge, E. A., The Book of Governors: The Historia Monastica of Thomas, Bishop of Marga, AD 840 (London, 1893)

- Wallis Budge, E. A., The Monks of Kublai Khan (London, 1928)

- Wilmshurst, D. J., The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913 (Louvain, 2000)

- Wilmshurst, D. J., The Martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East (London, 2011).