Deaf rights movement

The Deaf rights movement encompasses a series of social movements within the disability rights and cultural diversity movements that encourages deaf and hard of hearing people and society to adopt a position of respect for Deaf people, accepting deafness as a cultural identity and a variation in functioning rather than a communication disorder to be cured.

Deaf education

Oralism

Oralism focuses on teaching deaf students through oral communicative means rather than sign languages.

There is strong opposition within Deaf communities to the oralist method of teaching deaf children to speak and lip read with limited or no use of sign language in the classroom. The method is intended to make it easier for deaf children to integrate into hearing communities, but the benefits of learning in such an environment are disputed. The use of sign language is also central to Deaf identity and attempts to limit its use are viewed as an attack.

Deaf Schools

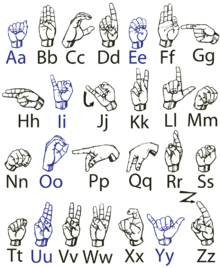

Parents of deaf children also have to opportunity to send their children to deaf schools, where the curriculum is taught in American Sign Language. The first school for the education of deaf individuals was the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons, which opened on April 15, 1817.[1] This was a coeducation insitiution.[1] This school was later renamed the American School for the Deaf, and was granted federal money to set up of deaf institutions around the country.[1] Many teachers in these schools were women, because according to PBS and the research done for the film Through Deaf Eyes, they were better at instructing due to the patience it took to do something repetitively.[2] The American School for the Deaf was set up based on a British model of education for deaf individuals with instruction in the subjects of reading, writing, history, math, and an advanced study of the Bible.[1]

Gallaudet University is the only deaf university in the world, which instructs in American Sign Language, and promotes research and publications for the deaf community.[3] Gallaudet University is responsible for expanding services and education for deaf individuals in developing countries around the world, as well as in the United States.[4] Many deaf individuals choose to be educated in a deaf environment for their college level education.[3]

Deaf President Now

Deaf President Now was a protest in Gallaudet University, a university for deaf and hard of hearing students, against its appointment of a hearing person as the president. Gallaudet had always been run by hearing presidents prior to the protest. As a result of the protests, I. King Jordan became the first deaf president of Gallaudet.

Public accommodations

Deaf individuals are given certain accommodations that help them in their daily lives. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, along with the amendments that followed the law, allowed deaf individuals certain rights that, previous to 1990, were not granted to deaf individuals.[5] The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed on July 26, 1990 by President George H.W. Bush.[6] The main benefit of the ADA was the right for deaf people to have access to interpreters, which in turn, allowed more equal access to education.[6] The ADA helped to ease the communication barrier between hearing individuals and the members of the deaf and hard of hearing communities, provide equal employment opportunities, and telecommunication devices.[7] The ADA also allows for equal opportunities for deaf and hard of hearing individuals by making it illegal to discriminate against these individuals on account of their disability.

Deaf culture movement

Deaf culture is a culture defined by usage of sign language and many cultural and social norms.

Cochlear implants

Within the Deaf community, there is strong opposition to the use of cochlear implants and sometimes also hearing aids and similar technologies. This is often justified in terms of a rejection of the view that deafness, as a condition, is something that needs to be fixed.

Others argue that this technology also threatens the continued existence of Deaf culture, but Kathryn Woodcock argues that it is a greater threat to Deaf culture to reject prospective members just because they used to hear, because their parents chose an implant for them, because they find environmental sound useful, etc.[8] Cochlear implants may improve the perception of sound for suitable implantees, but they do not reverse deafness, or create a normal perception of sounds.

The statement that deafness is not a disability, disorder or disease

Many Deaf people and Deaf linguists reject the idea deafness is a disability.[9] However, some disability rights activists consider this rejection to be the result of internalized ableism.[10]

See also

- Deaf culture

- Sign language

- Deaf education

- Models of deafness

- Audism

- Surdophobia

- Deaf President Now

- Disability rights movement

- Deafhood

References

- 1 2 3 4 Crowley, John. "Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb". www.disabilitymuseum.org. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Oral Education and Women in the Classroom". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- 1 2 "Gallaudet University". www2.gallaudet.edu. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- ↑ "Reviewing The Pioneering Roles Of Gallaudet University Alumni In Advancing Deaf Education And Services In Developing Countries: Insights And Challenges From Nigeria." American Annals Of The Deaf 2 (2015): 75. Project MUSE. Web. 15 Mar. 2016.

- ↑ "Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990,AS AMENDED with ADA Amendments Act of 2008". www.ada.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- 1 2 Stanton, John F. "Breaking The Sound Barriers: How The Americans With Disabilities Act And Technology Have Enabled Deaf Lawyers To Succeed." Valparaiso University Law Review 45.3 (2011): 1185-1245. Index to Legal Periodicals & Books Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 15 Mar. 2016.

- ↑ Legal Rights. [Electronic Resource] : The Guide For Deaf And Hard Of Hearing People. n.p.: Washington, DC : Gallaudet University Press, [2015] (Baltimore, Md. : Project MUSE, 2015), 2015. Louisiana State University. Web. 15 Mar. 2016.

- ↑ Woodcock, Kathryn (1992). Cochlear Implants vs. Deaf Culture? In Mervin Garretson (ed.), Viewpoints on Deafness: A Deaf American Monograph. Silver Spring, MD: National Association for the Deaf.

- ↑ Ladd, Paddy (2003). Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood. Multilingual Matters. p. 502. ISBN 1-85359-545-4.

- ↑ Fleischer, Doris Zames; Zames, Frieda (June 2011). "The Disability Rights Movement: From Charity to Confrontation": 14–32. JSTOR j.ctt14bt7kv.