De Rivaz engine

The de Rivaz engine was a pioneering reciprocating engine designed and developed from 1804 by the Franco-Swiss inventor Isaac de Rivaz. The engine has a claim to be the world's first internal combustion engine and contained some features of modern engines including spark ignition and the use of hydrogen gas as a fuel.

Starting with a stationary engine suitable to work a pump in 1804, de Rivaz progressed to a small experimental vehicle built in 1807, which was the first wheeled vehicle to be powered by an internal combustion engine. In subsequent years de Rivaz developed his design, and in 1813 built a larger 6-meter long vehicle, weighing almost a ton.

Background

Towards the end of the 18th century Isaac de Rivaz, a Franco-Swiss artillery officer and inventor, designed several successful steam powered carriages, or charettes as he called them in the French language. His army experience with cannon had led him to think about using an explosive charge to drive a piston instead of steam.[1] In 1804 he began to experiment with explosions created inside a cylinder with a piston. His first designs were for a stationary engine to power a pump.[2] The engine was powered by a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen gases ignited to create an explosion within the cylinder and drive the piston out. The gas mixture was ignited by an electric spark in the same manner as a modern internal combustion engine. In 1806 he moved on to apply the design to what became the world's first internal combustion engine driven automobile.[3][4]

In 1807 de Rivaz placed his experimental prototype engine in a carriage and used it to propel the vehicle a short distance. This was the first vehicle to be powered by an internal combustion engine. On 30 January 1807 Isaac de Rivaz was granted patent No. 731 in Paris. A patent in the State of Valais (now Swiss) patent office also dates it to 1807.[1][3][5]

Operating independently, the French brothers Nicéphore and Claude Niépce built an internal combustion engine called the Pyreolophore in 1807, which they used to power a boat by the reaction from a pulsed water jet. The honour of whose design was the first internal combustion engine is still debated. The Niépce patent is dated 20 July 1807.[6]

Operation

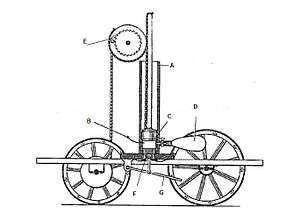

The de Rivaz engine had no timing mechanism and the introduction of the fuel mixture and ignition were all under manual control. The compressed hydrogen gas fuel was stored in a balloon connected by a pipe to the cylinder. Oxygen was supplied from the air by a separate air inlet. Manually operated valves allowed introduction of the gas and air at the correct point in the cycle. A lever worked by hand moved a secondary, opposed, piston. This evacuated the exhaust gases, sucked in a fresh mixture and closed the inlet and exhaust valves. A Volta cell was used to ignite the gas within the cylinder by pressing an external button that created an electric spark inside the cylinder.[1][7]

The explosion drove the piston freely up the vertically mounted cylinder, storing the energy by lifting the heavy piston to an elevated position.[8] The piston returned under its own weight and engaged a ratchet that connected the piston rod to a pulley. This pulley was in turn attached to a drum around which a rope was wound. The rope's other end was attached to a second drum on the charette's front wheels. The weight of the piston during its return down the cylinder was enough to turn the drums and move the charette. When the return stroke was over, the ratchet allowed the top drum to disconnect from the piston rod ready for the next powered lift of the piston.[1][7][8]

Around 1985 the Giannada Automobile Museum produced two reconstructions of the charette, a model about 50 cm long and a larger working one about 2 meters long. The working model used air pressure to simulate the gas/chemical explosion. On one occasion this car moved about 100 meters in front of the museum as part of a demonstration.[9]

Later vehicles

In 1813 de Rivaz built a much larger experimental vehicle he called the grand char mécanique. This was 6 meters long, equipped with wheels of two meters in diameter and weighed almost a ton. The cylinder was 1.5 meters long and the piston had a stroke of 97 cm. The explosive gas mixture used was now composed of about 2 liters of coal gas and 10 to 12 liters of air.[1] In the Swiss town of Vevey the machine, was loaded with 700 pounds of stone and wood together with four men and ran for 26 meters on a slope of about 9% at a speed of 3 km/h. With each stroke of the piston, the vehicle moved ahead from four to six meters.[3]

Few of his contemporaries took his work seriously. The French Academy of Sciences argued that the internal combustion engine would never rival the performance of the steam engine.[1]

See also

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- Pyréolophore another internal combustion engine approach from the same historical era.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Michelet, Henri (1965). L'inventeur Isaac de Rivaz: 1752 – 1828 (in French). Editions Saint-Augustin. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ Cleveland, Cutler; Tom Lawrence (August 24, 2008). "De Rivaz, François Isaac". Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Archived from the original on April 16, 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- 1 2 3 "Car History: The chronology". Cybersteering.com. 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ↑ Andrews, John (2007). "Hydrogen Cars and Land Speed Record". H2-Hydro-Gen. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- ↑ "L'inventeur du moteur à explosion" (in French). Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- ↑ "Other Inventions: The Pyrelophore". Niépce House Museum. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Hydrogen Fuel Cars 1807 – 1986". Hydrogen Fuel Cars Now. 2005–2011.

- 1 2 Eckermann, Erik (2001). World history of the automobile. SAE. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-7680-0800-X. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- ↑ "de Rivaz family History". 2 March 2006.