David Hampton

| David Hampton | |

|---|---|

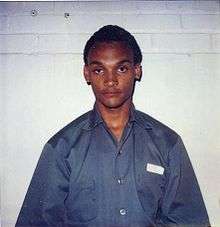

Mug shot of David Hampton, taken by New York State Department of Correctional Services on January 10, 1985, after Hampton was arrested for attempted burglary. | |

| Born |

April 28, 1964 Buffalo, New York |

| Died |

July 18, 2003 (aged 39) Beth Israel Medical Center Manhattan, New York City |

| Other names | David Poitier, Patrick Owens, Antonio Jones, David Hampton-Montilio |

| Criminal charge | Fraud, fare-beating, credit-card theft, threats of violence, burglary, harassment |

| Criminal penalty | Twenty-one month prison term |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Attempted burglary |

David Hampton (April 28, 1964 – July 18, 2003) was an American con artist and robber who became infamous in the 1980s after he managed to convince a group of wealthy Manhattanites to give him money, food, and shelter, convincing them he was the son of Sidney Poitier. His story became the inspiration for a play and a film. He died of AIDS-related complications in 2003.

Background

Hampton was born in Buffalo, New York and was the eldest son of an attorney. He moved to New York City in 1981 and stumbled upon his now-famous ruse in 1983 when he and another man were attempting to gain entry into Studio 54. Unable to obtain entry, Hampton's partner decided to pose as Gregory Peck's son while Hampton assumed the identity of Sidney Poitier's son. They were ushered in as celebrities. Hampton began employing the persona of "David Poitier" to cadge free meals in restaurants. He also persuaded at least a dozen people into letting him stay with them and give him money, including Melanie Griffith, Gary Sinise, Calvin Klein; John Jay Iselin, the president of WNET; Osborn Elliott, the dean of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism; and a Manhattan urologist. He convinced some that he was an acquaintance of their children, some that he had just missed a plane to Los Angeles with his luggage still on it, and some that his belongings had been stolen.[1][2]

In October 1983, Hampton was arrested and convicted for his frauds and was ordered to pay restitution of $4,490 to his various victims. After refusing to comply with these terms, he was sentenced to a term of 18 months to 4 years in prison.

Six Degrees of Separation

Playwright John Guare became interested in Hampton's story through his friendship with Inger McCabe Elliott and Osborn Elliott, who had been outraged to find "David Poitier" in bed with another man the morning after they let him into their home. Six Degrees of Separation opened at the Lincoln Center in May 1990 and became a long-running success.[3]

Hampton attempted to parlay the play's success to his benefit, giving interviews to the press, gate-crashing a producer's party, and beginning a campaign of harassment against Guare that included phone calls and death threats, prompting Guare to apply for a restraining order in April 1991, which was unsuccessful. In the fall of 1991, Hampton filed a $100 million lawsuit, claiming that the play had infringed on the copyright on his persona and his story. The lawsuit was eventually dismissed.

Later life

After his release, Hampton continued to adopt false identities. After the play and film made his original con well-known, Hampton evolved other false identities and traveled extensively to find new victims. Hampton was in and out of prison in numerous states. He was interviewed during each break from incarceration by a journalist with the TV show The Justice Files, seen in the USA on Discovery Channel.

After declaring his rehabilitation, Hampton continued traveling at least as late as 1996, where he found a large number of men who, even if they'd heard of his notoriety from the East Coast, had never seen his picture or the press, allowing him to move about unnoticed and simultaneously con multiple victims. In Spring 1996, Hampton arrived in Seattle, Washington, USA, posing as Antonio de Montilio, the son of a wealthy District of Columbia physician. Due to his light skin color, victims claimed he could easily be believed as the Puerto Rican he claimed to be. Typically, his story was colorful. Hampton claimed to have been mugged upon arriving in Seattle early for a work assignment for Vogue magazine. He was to interview Bill Gates but was suddenly in peril as his wallet was stolen and nothing could be replaced until that weekend was over. Hampton managed to woo two people within blocks of each other without their being aware that he was working them both. It is believed that he was first drawn to one victim, Justin Baird, because Baird had been identified at RPlace as the official taking in fundraising dollars from Bunny Brigade volunteers as they returned from their collection rounds.

David Hampton died of AIDS-related complications while being treated for his illness at Beth Israel Hospital in Manhattan.[4]

See also

- Alan Conway, a con-artist with a similar modus operandi

References

- ↑ "Obituary: David Hampton". telegraph.co.uk. 2003-07-22. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Witchel, Alex (1990-06-21). "The Life of Fakery and Delusion In John Guare's 'Six Degrees'". nytimes.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Kasindorf, Jeanie (1991-03-25). "Six Degrees of Impersonation". New York Magazine. p. 40. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ↑ Jones, Kenneth (2003-07-20). "David Hampton, Con-Man Whose Exploits Inspired Six Degrees, Dead at 38". playbill.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

David Hampton, the inspiration for the young black con-man who fools white New York society in John Guare's popular play, Six Degrees of Separation, died at New York's Beth Israel Hospital, a friend told newspapers and wire services. Mr. Hampton was 39 and the cause of death was apparently complications from AIDS.

External links

- Suspect in Hoax is Arrested Here in Rendezvous at nytimes.com (October 19, 1983)

- Teen-Ager Who Posed As Poitier 'Son' Guilty at nytimes.com (November 20, 1983)

- Impersonator Wants To Portray Still Others, This Time, Onstage at nytimes.com (July 31, 1990)

- HEADLINERS; Playing Himself at nytimes.com (August 5, 1990)

- About New York; He Conned the Society Crowd but Died Alone at nytimes.com (July 19, 2003)