Darién Gap

The Darién Gap (Spanish: Región del Darién or Tapón del Darién) is a break in the Pan-American Highway consisting of a large swath of undeveloped swampland and forest within Panama's Darién Province in Central America and the northern portion of Colombia's Chocó Department in South America. It measures just over 160 km (99 mi) long and about 50 km (31 mi) wide. Roadbuilding through this area is expensive, and the environmental cost is high. Political consensus in favor of road construction has not emerged. Consequently there is no road connection through the Darién Gap connecting North America with South America and it is the missing link of the Pan-American Highway.

The geography of the Darién Gap on the Colombian side is dominated primarily by the river delta of the Atrato River, which creates a flat marshland at least 80 km (50 mi) wide, half of this being swampland. The Serranía del Baudó range extends along Colombia's Pacific coast and extends into Panama. The Panamanian side, in sharp contrast, is a mountainous rainforest, with terrain reaching from 60 m (200 ft) in the valley floors to 1,845 m (6,053 ft) at the tallest peak (Cerro Tacarcuna, in the Serranía del Darién).

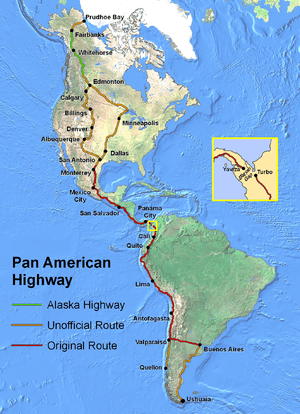

Pan-American Highway

The Pan-American Highway is a system of roads measuring about 48,000 km (30,000 mi) long that crosses through the entirety of North, Central, and South America, with the sole exception of the Darién Gap. On the South American side, the highway terminates at Turbo, Colombia near 8°6′N 76°40′W / 8.100°N 76.667°W. On the Panamanian side, the road terminus is the town of Yaviza at 8°9′N 77°41′W / 8.150°N 77.683°W. This marks a straight-line separation of about 100 km (60 mi). In between is marshland and forest.

Efforts have been made for decades to remedy this missing link in the Pan-American highway. Planning began in 1971 with the help of United States funding, but this was halted in 1974 after concerns raised by environmentalists. Another effort to build the road began in 1992, but by 1994 a United Nations agency reported that the road, and the subsequent development, would cause extensive environmental damage. Cited reasons include evidence that the Darién Gap has prevented the spread of diseased cattle into Central and North America, which have not seen foot-and-mouth disease since 1954, and since at least the 1970s this has been a substantial factor in preventing a road link through the Darién Gap.[1][2] The Embera-Wounaan and Kuna have also expressed concern that the road would bring about the potential erosion of their cultures.

Many people, groups, indigenous populations, and governments are opposed to completing the Darién portion of the highway. Reasons for opposition include protecting the rain forest, containing the spread of tropical diseases, protecting the livelihood of indigenous peoples in the area, preventing drug trafficking[3] and its associated violence, and preventing foot-and-mouth disease from entering North America. The extension of the highway as far as Yaviza resulted in severe deforestation alongside the highway route within a decade.

One option proposed, in a study by Bio-Pacifico, is a short ferry link from Colombia to a new ferry port in Panama, with an extension of the existing Panama highway that would complete the highway without violating these environmental concerns. Another idea is to use a combination of bridges and tunnels to avoid the environmentally sensitive regions.[4] The Everglades Skyway is an example of an environmentally conscious bridge being developed over the Florida Everglades in order to avoid the environmental impact of a conventional roadway.

The gap has been crossed by adventurers on bicycle, motorbike, all-terrain vehicle, and foot, dealing with jungle, swamp, insects, and other hazards.

Within the gap

People

The Darién Gap is home to the Embera-Wounaan and Kuna (and the former home of the Cueva people before their extermination in the 16th century). Travel is often by dugout canoe (piragua). On the Panamanian side, La Palma is the capital of the province and the main cultural centre. Other mestizo population centers include Yaviza and El Real. The Darién Gap had a reported population of 1,700 in 1980. Corn, cassava, plantains, and bananas are staple crops wherever land is developed.

Natural resources

Two major national parks exist in the Darién Gap: Darién National Park (Spanish: Parque Nacional Darién) in Panama and Los Katíos National Park (Spanish: Parque Nacional de Los Katíos) in Colombia. The Darién Gap forests had extensive cedrela and mahogany cover at one time, but many of these trees were removed by loggers.

Darién National Park covers around 5,790 square kilometres of land and was established in 1980. It is the largest national park in Central America.

Crossings of the Darién Gap

The Gap can be transited by off-road vehicles attempting intercontinental journeys. The first post-colonial expedition to the Darién was the Marsh Darien Expedition[5] in 1924–5, supported by several major sponsors, including the Smithsonian Institution.

The first vehicular crossing of the Gap was by the Land Rover La Cucaracha Cariñosa (The Affectionate Cockroach) and a Jeep of the Trans-Darién Expedition of 1959–60, crewed by Amado Araúz (Panama), his wife Reina Torres de Araúz, former Special Air Service man Richard E. Bevir (UK), and engineer Terence John Whitfield (Australia).[6] They left Chepo, Panama, on 2 February 1960 and reached Quibdó, Colombia, on 17 June 1960, averaging 201 m (220 yd) per hour over 136 days. They traveled a great deal of the distance up the vast Atrato River.

In December 1960, on a motorcycle trip from Alaska to Argentina, adventurer Danny Liska[7] attempted to transit the Darién Gap from Panama to Colombia.[8] Liska was forced to abandon his motorcycle and proceed across the Gap by boat and foot. In 1961, a team of three 1961 Chevrolet Corvairs and several support vehicles departed from Panama. The group was sponsored by Dick Doane Chevrolet (a Chicago Chevrolet dealer) and the Chevrolet division of General Motors. After 109 days they reached the Colombia Border with two Corvairs, the third having been abandoned in the jungle. This was the first crossing by a standard two wheel drive passenger car. It has been documented by a Jam Handy Productions film along with an article in Automobile Quarterly magazine (Volume 1 number 3, from the fall of 1962).

A pair of Range Rovers was used on the British Trans-Americas Expedition in 1972 led by John Blashford-Snell, which is claimed to be the first vehicle-based expedition to traverse both American continents north to south through the Darién Gap. The Expedition crossed the Atrato Swamp in Colombia with the cars on special inflatable rafts that were carried in the backs of the vehicles. However, they received substantial support from the British Army. Blashford-Snell's book, Something Lost Behind the Ranges (Harper Collins) has several chapters on the Darién expedition. The Hundred Days of Darien, a book written by Russell Braddon in 1974, also chronicles this expedition.

The first fully overland wheeled crossing (others used boats for some sections) of the Gap was that of British cyclist Ian Hibell, who rode from Cape Horn to Alaska between 1971 and 1973. Hibell took the "direct" overland south-to-north route, including an overland crossing of the Atrato Swamp in Colombia. Hibell completed his crossing of the Gap accompanied by two New Zealand cycling companions who had ridden with him from Cape Horn, but neither of these continued with Hibell on to Alaska. Hibell's "Cape Horn to Alaska" expedition forms part of his 1984 book Into the Remote Places.

The first motorcycle crossing was by Robert L. Webb in March 1975. Another four-wheel drive crossing was in 1978–1979 by Mark A. Smith and his team. Smith and his team drove the 400 km (250 mi) stretch of the gap in 30 days using five stock Jeep CJ-7s. They travelled many miles up the Atrato River on barges. Smith has released his book, Driven by a Dream, which documents the crossing.

The first all-land auto crossing was in 1985–87 by Loren Upton and Patty Mercier in a CJ-5 Jeep, taking 741 days to travel 125 miles (201 km). This crossing is documented in the 1992 Guinness Book of Records. Ed Culberson was the first one to follow the entire Pan-American highway including the Darién Gap proposed route on a motorcycle, a BMW R80G/S. From Yaviza he first followed the Loren Upton team but would go solo just before Pucuru, hiring his own guides.[9]

In the 1990s, the gap was briefly joined by ferry service, provided by Crucero Express, but this company ceased operations in 1997.

There have been several notable crossings by foot. Sebastian Snow crossed the Gap with Wade Davis in 1975 as part of his unbroken walk from Tierra del Fuego to Costa Rica. The trip is documented in his 1976 book The Rucksack Man. In 1981, George Meegan crossed the gap on a similar journey. He too started in Tierra del Fuego and eventually ended in Alaska. His 1988 biography, The Longest Walk, describes the trip and includes a 25-page chapter on his foray through the Gap. In 2001, as a part of his Goliath Expedition—a trek to forge an unbroken footpath from the tip of South America to the Bering Strait and back to his home in England—Karl Bushby (UK) crossed the gap on foot, using no transport or boats, from Colombia to Panama.

In 1979 evangelist Arthur Blessitt traversed the gap while carrying a 12-foot wooden cross, a trek confirmed by Guinness World Records as part of "the longest round the world pilgrimage" for Christ. Traveling alone with a machete plus one backpack crammed with water bottles, a hammock, Bible, notepad, lemon drops, and Blessitt's signature Jesus stickers saying "Smile! God Loves you", Blessitt describes his experience in a book, The Cross, and in a full-length movie of the same name.[10][11][12][13]

Most crossings of the Darién Gap region have been from Panama to Colombia. In July 1961, three college students crossed from the Bay of San Miguel to Puerto Obaldia on the Gulf of Parita (near Colombia) and ultimately to Mulatupu in what was then known as San Blas and now identified as Kuna Yala. The trip across the Darién was by banana boat, piraqua, and foot via the Tuira river (La Palma and El Real de Santa Maria), Río Chucunaque (Yaviza), Rio Tuquesa (Chaua's (General Choco Chief) Trading Post—Choco Indian village) and Serranía del Darién.[14][15]

In 1985, Project Raleigh, which evolved from Project Drake in 1984 and in 1989 became Raleigh International, sponsored an expedition which also crossed the Darién coast to coast.[16] Their path was similar to the 1961 route above, but in reverse. The expedition started in The Bay of Caledonia at the Serranía del Darién and followed the Río Membrillo ultimately to the Río Chucunaque and Yaviza, roughly following the route taken by Balboa in 1513.

Between the early 1980s and mid-1990s a British adventure travel company, Encounter Overland, organized 2–3 week trekking trips through the Darién Gap from Panama to Colombia or vice versa. These trips used a combination of whatever transport was available: jeeps, bus, boats, and of course plenty of walking, with travellers carrying their own supplies. These groups were made up of male and female participants from any number of nationalities and age groups, and were led by experienced trek leaders. One leader went on to do nine Darién Gap trips and later acted as a logistics guide and coordinator for the BBC Natural History Unit during the production of a documentary called A Tramp in the Darien, which screened on BBC in 1990–91.

A complete overland crossing of the Darién rainforest by foot and riverboat (i.e., from the last road in Panama to the first road in Colombia) became more dangerous in the 1990s because of the Colombian conflict. The Colombian portion of the Darién rainforest in the Katios Park region eventually fell under control of armed groups. Furthermore, combatants from Colombia even entered Panama, occupied some Panamanian jungle villages and kidnapped or killed inhabitants and travelers. Just as hostilities were starting to worsen, 18-year-old Andrew Egan traversed the Darien Rainforest, detailing the excursion in the book Crossing the Darien Gap.

As of 2013, the coastal route on the east side of the Darién Isthmus has become relatively safe. This is by motorboat across the Gulf of Uraba from Turbo to Capurganá, and then hopping the coast to Sapzurro and hike from there to La Miel (Panama). Any inland routes through the Darien remain highly dangerous.[17]

From May 2013, Colombian neo-paramilitary forces were reported to be very active in the Darien around Los Katios National Park and the Cuenca Cacarica [18]

Migrants from Africa have been known to cross the Darién Gap as a method of migrating to the United States. This route may entail flying to Ecuador (taking advantage of that nation's liberal visa policy), and attempting to cross the gap on foot. [19] The journalist Jason Motlagh was interviewed by Sacha Pfeiffer on NPR's nationally syndicated radio show On Point in 2016 concerning his work following migrants through the Darién Gap.[20]

Armed conflict and kidnappings

The Darién Gap is subject to the presence and activities of the Marxist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which has committed assassinations, kidnappings, and human rights violations during its decades-long insurgency against the Colombian government.[21] FARC rebels are present on both the Colombian and Panamanian sides of the border.[22] In 2000, two British travellers, Tom Hart Dyke and Paul Winder, were kidnapped by suspected FARC guerillas in the Darién Gap while hunting for rare orchids, a plant for which Dyke has a particular passion. The two were held captive for nine months and threatened with death before eventually being released unharmed and without a ransom being paid. Dyke and Winder later documented their experience in the book The Cloud Garden and an episode of Locked Up Abroad.

Other political victims of the Darién Gap include three New Tribes missionaries, who disappeared from Pucuro on the Panamanian side in 1993.[23]

In 2003, Robert Young Pelton, on assignment for National Geographic Adventure magazine, and two traveling companions, Mark Wedeven and Megan Smaker, were detained for one week by the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, a pro-government paramilitary organization, in a highly publicized incident.[24][25]

In 2013, Swedish backpacker Jan Philip Braunisch disappeared in the area after leaving the Colombian town of Riosucio with the intention of attempting a crossing on foot to Panama, via the Cuenca Cacarica. His skeletal remains were recovered in June 2015 with evidence he had been killed with a shot in the head. The FARC admitted to killing him confusing him for a foreign spy.[26]

In popular culture

The Darién gap is referenced directly in the 2014 film Indigenous. It is also mentioned in John Keats' poem "On First Looking into Chapman's Homer" and Arthur Ransome's 'Swallows and Amazons', where the children name a promontory after Keats' poem.

It was also referenced in Prison Break as the location where the two main protagonists intended to hide after their prison escape.

Further, it is a major part of the plot in the film "The Art of Travel", where the protagonist joins a group that are intent on crossing the Darien Gap in record time.

See also

References

- ↑ U.S. GAO - Transportation: Construction Progress and Problems of the Darien Gap Highway

- ↑ Press Releases 2011 | Embassy of the United States Panama

- ↑ Perilla, Jisel (4 January 2011). Frommer's Panama. John Wiley & Sons. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-118-00112-7.

- ↑ http://www.futuristspeaker.com/2014/12/the-coming-era-of-mega-systems-part-1-transportation/ The Coming Era of Mega Systems, Part 1 – Transportation

- ↑ Marsh Darien Expedition

- ↑ Trans Darien Expedition

- ↑ Danny Liska Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Danny Liska "Across the Darien Gap by River and Trail II", Peruvian Times, Vol XXI, Num. 1068(June 2, 1961), pg. 10

- ↑ Obsessions Die Hard

- ↑ Longest ongoing pilgrimage

- ↑ The Cross: Arthur Blessitt: Amazon.com: Books

- ↑ The Cross

- ↑ Welcome to The Official Website of Arthur Blessitt

- ↑ "Brought Back Darien Bush", Panama Star & Herald], July 9, 1961, pg. 1

- ↑ Carl Adler, "A Trip to Panama", The Scholastic, Vol. 104, No. 11, January 18, 1963, pg. 18

- ↑ "After Trek Through the Jungle Youth's Ready to Go Again". Raleigh The News & Observer, June 25, 1985

- ↑ Crossing the Darien Gap, documentary film (2013), March 2013.

- ↑ Paramilitaries intensify operations in Uraba and Choco (2013), October 2013.

- ↑ Kahn, Carrie (22 June 2016). "ia Cargo Ships and Jungle Treks, Africans Dream Of Reaching The U.S. 5:02 Queue Download Embed Transcript Facebook Twitter Google+ Email June 22, 20165:27 PM ET". NPR. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "Stories From The Dangerous Darién Gap | On Point". Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ↑ Amnesty International | Working to Protect Human Rights

- ↑ "Panama's Darien teems with FARC drug runners". Reuters. 26 May 2010.

- ↑ Alford, Deann (1 September 2001). "New Tribes Missionaries Kidnapped in 1993 Declared Dead". Christianity Today. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ↑ "3 Americans freed, 2 journalists still captive in Colombia". CNN.com. 2003-01-24. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ↑ Markey, Sean (2003-01-22). "Adventure Writer Reportedly Kidnapped in Panama". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ "FARC admits to killing Swedish tourist in northwest Colombia". Retrieved 2015-10-06.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Darien Gap. |

- "Pan-American Highway and the Environment"

- "A State of Nature: Life, Death, and Tourism in the Darién Gap", 2013

Coordinates: 7°54′N 77°28′W / 7.90°N 77.46°W