Canal of the Pharaohs

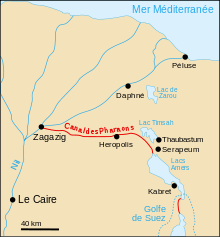

The Canal of the Pharaohs, also called the Ancient Suez Canal or Necho's Canal, is the forerunner of the Suez Canal, constructed in ancient times. It followed a different course than its modern counterpart, by linking the Nile to the Red Sea via the Wadi Tumilat. Work began under the Pharaohs. According to Suez Inscriptions and Herodotus, the first opening of the canal was under Persian king Darius the Great,[1][2][3][4] but later ancient authors like Aristotle, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder claim that he failed to complete the work.[5] Another possibility is that it was finished in the Ptolemaic period under Ptolemy II, when Greek engineers solved the problem of overcoming the difference in height through canal locks.[6][7][8]

Egyptian and Persian works

Probably first cut or at least begun by Necho II, in the late 6th century BC, Darius the Great either re-dug or completed it. Exactly when it was finally completed is not known as the classical sources disagree.

Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions comprise five Egyptian monuments, including the Chalouf Stele[9] commemorate the construction and completion of the canal linking the Nile River with the Red Sea by Darius I of Persia.[10] They were located along the Darius Canal through the valley of Wadi Tumilat and probably recorded sections of the canal as well.[11] In the second half of the 19th century, French cartographers discovered the remnants of the north–south section of Darius Canal past the east side of Lake Timsah and ending near the north end of the Great Bitter Lake.[12]

At least as far back as Aristotle there have been suggestions that perhaps as early as the 12th Dynasty, Pharaoh Senusret III (1878 BC–1839 BC), also called Sesostris, may have started a canal joining the River Nile with the Red Sea. In his Meteorology, Aristotle wrote:

One of their kings tried to make a canal to it (for it would have been of no little advantage to them for the whole region to have become navigable; Sesostris is said to have been the first of the ancient kings to try), but he found that the sea was higher than the land. So he first, and Darius afterwards, stopped making the canal, lest the sea should mix with the river water and spoil it.[13]

Strabo also wrote that Sesostris started to build a canal, and Pliny the Elder wrote:

165. Next comes the Tyro tribe and, on the Red Sea, the harbour of the Daneoi, from which Sesostris, king of Egypt, intended to carry a ship-canal to where the Nile flows into what is known as the Delta; this is a distance of over 60 miles. Later the Persian king Darius had the same idea, and yet again Ptolemy II, who made a trench 100 feet wide, 30 feet deep and about 35 miles long, as far as the Bitter Lakes.[14]

Although Herodotus (2.158) tells us Darius I continued work on the canal,[15] Aristotle (Aristot. met. I 14 P 352b.), Strabo (Strab. XVII 1, 25 C 804. 805.), and Pliny the Elder (Plin. n. h. VI 165f.) all say that he failed to complete it,[15] while Diodorus Siculus does not mention a completion of the canal by Necho II.[16] Pliny the Elder also says that Ptolemy II, who took up the work again, also stopped because of the differences of water level.[11] Diodorus, however, reports that it was completed by Ptolemy II after being fitted with a lock.[17]

Greek, Roman and Islamic works

Ptolemy II was the first to solve the problem of keeping the Nile free of salt water when his engineers invented the water lock around 274/273 BC.[18]

In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy the Astronomer mentions a "River of Trajan", a Roman canal running from the Nile to the Red Sea.

Islamic texts also discuss the canal, which they say had been silted up by the seventh century but reopened in 641 or 642 AD by 'Amr ibn al-'As, the conqueror of Egypt, and which was in use until closed in 767 AD in order to stop supplies reaching Mecca and Medina which were in rebellion.[11]

Thereafter, the land routes to tranship camel caravans' goods were from Alexandria to ports on the Red Sea or the northern Byzantine silk route through the Caucasian Mountains transhipping on the Caspian Sea and thence to India.

During his Egyptian expedition, Napoleon found the canal in 1799.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1994-12-15). "DARIUS iii. Darius I the Great". Encyclopedia Iranica. New York. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbraun. p. 384 & 479. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. "Darius' Suez Inscriptions". Livius.org. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ↑ Munn-Rankin, J.M. (2011). "Darius I". London: Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ↑ Schörner 2000, p. 31, 40, fn. 33

- ↑ Moore 1950, pp. 99–101

- ↑ Froriep 1986, p. 46

- ↑ Schörner 2000, pp. 33–35

- ↑ William Matthew Flinders Petrie, A History of Egypt. Volume 3: From the XIXth to the XXXth Dynasties, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 0-543-99326-4, p. 366

- ↑ Barbara Watterson (1997), The Egyptians, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-21195-0, p.186

- 1 2 3 Redmount, Carol A. "The Wadi Tumilat and the "Canal of the Pharaohs"" Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Apr., 1995), pp. 127-135

- ↑ Carte hydrographique de l'Basse Egypte et d'une partie de l'Isthme de Suez (1855, 1882). Volume 87, page 803. Paris. See .

- ↑ Meteorology (1.15)

- ↑ The Elder Pliny and John Healey Natural History (6.33.165) Penguin Classics; Reprint edition (5 Feb 2004) ISBN 978-0-14-044413-1 p.70

- 1 2 Schörner 2000, p. 40, fn. 33

- ↑ Schörner 2000, p. 31

- ↑ Schörner 2000, p. 34

- ↑ Gmirkin, Russell Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch T.& T.Clark Ltd (24 Aug 2006) ISBN 978-0-567-02592-0 p.236

References

- Froriep, Siegfried (1986): "Ein Wasserweg in Bithynien. Bemühungen der Römer, Byzantiner und Osmanen", Antike Welt, 2nd Special Edition, pp. 39–50

- Moore, Frank Gardner (1950): "Three Canal Projects, Roman and Byzantine", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 97–111

- Schörner, Hadwiga (2000): "Künstliche Schiffahrtskanäle in der Antike. Der sogenannte antike Suez-Kanal", Skyllis, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 28–43