Curtana

Curtana, also known as the Sword of Mercy, is a ceremonial sword used at the coronation of British kings and queens. One of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, its end is blunt and squared, said to symbolize mercy. It is linked to the legendary sword carried by Tristan and Ogier the Dane.

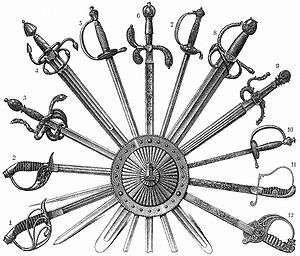

Description

The sword measures 96.5 centimetres (38 in) long and 19 centimetres (7.5 in) wide at the handle. About 2.5 centimetres (1 in) of the steel blade's tip is missing. The blade features a decorative 'running wolf' mark which originated in the town of Passau, Lower Bavaria, Germany.[1] It has a gilt-iron hilt, a wooden grip bound in wire, and a leather sheath bound in crimson velvet with gold embroidery that was made in 1821.[2]

History

A coronation sword named Curtana (from the Latin Curtus, meaning short[3]) is first documented in the reign of Henry III of England as one of three swords employed in the coronation of Queen Eleanor of Provence in 1236.[4][5] The coronation tradition involving three swords (Curtana being principal among them[6]) dates back at least to Richard I (reigned 1189–99), though the individual swords' meanings have changed over time.[5]

Henry III's Curtana was said to have been the sword of the legendary knight Tristan. This connection may have come about due to its broken end, as Tristan was said to have left a piece of his sword in the skull of Morholt.[4] A sword named "Cortana", "Curtana", etc., was also attributed to Ogier the Dane, one of Emperor Charlemagne's paladins in the Matter of France. According to legend, it bore the inscription "My name is Cortana, of the same steel and temper as Joyeuse and Durendal",[7] and when Ogier was about to slay the son of Charlemagne, an angel appeared and knocked it out of his hand, breaking the tip and exclaiming "Mercy is better than revenge!"[1] The 13th-century Prose Tristan states that Ogier had inherited Tristan's sword, shortening it and naming it Cortaine; this suggests the author knew the tradition connecting Henry's Curtana to Tristan.[4][8]

The meaning attributed to Curtana and the other two British coronation swords shifted over time. During the coronation of Henry IV, Curtana was evidently considered to be the "Sword of Justice", while a second sword was the "Sword of the Church". Eventually, however, Curtana's blunt edge was taken to represent mercy, and it thus came to be known as the Sword of Mercy. Henry VI's coronation featured Curtana as the Sword of Mercy along with two other swords: the sharply-pointed Sword of Temporal Justice and the more obtuse Sword of Spiritual Justice; these designations remain today.[5][1]

The current sword was likely made for Charles I's coronation in 1626. Before then, a new sword was generally made for each coronation. A royal cutler supplied the sword but its blade was actually created in the 1580s by Italian bladesmiths Giandonato and Andrea Ferrara.[9] Together with the other two swords and the Coronation Spoon, it is one of the few pieces of the Crown Jewels to have survived the English Civil War intact. It is not clear if the swords were used by Charles II but they have been used continuously since the coronation of his successor James II in 1685.[2]

Use

Until the 14th century, it was the job of the Earl of Chester to carry the sword before the monarch at his or her coronation. Today, another high-ranking peer of the realm is chosen by the monarch for this privilege.[10] When not in use, the sword is on display with the other Crown Jewels in the Jewel House at the Tower of London.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kenneth J. Mears; Simon Thurley; Claire Murphy (1994). The Crown Jewels. Historic Royal Palaces. p. 9. ASIN B000HHY1ZQ.

- 1 2 The Sword of Mercy at the Royal Collection.

- ↑ Concise English Dictionary. Wordsworth Editions. 1993. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-84022-497-9.

- 1 2 3 Christopher Harper-Bill; Ruth Harvey (1990). The Ideals and Practice of Medieval Knighthood III. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-0-85115-265-3.

- 1 2 3 Leopold George Wickham Legg (1901). English Coronation Records. A. Constable & Co. pp. xxiii–xv. ASIN B002WTYP2Q.

- ↑ Sir James Sibbald David Scott (1868). The British Army: Its Origin, Progress, and Equipment. Cassell, Petter & Galpin. p. 170.

- ↑ Thomas Bulfinch (1999). Bulfinch's Mythology: Legends of Charlemagne. Random House. p. 1247. ISBN 978-0-679-64001-1.

- ↑ Edmund Garratt Gardner (2003). Arthurian Legend in Italian Literature. Kessinger Publishing. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7661-5870-2.

- ↑ Anna Keay (2011). The Crown Jewels: The Official Illustrated History. Thames & Hudson. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-500-51575-4.

- ↑ George Younghusband; Cyril Davenport (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. Cassell & Co. p. 38. ASIN B00086FM86.