CryoSat-2

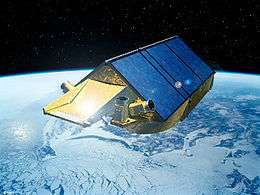

Artist's impression of CryoSat in orbit | |

| Mission type | Earth observation |

|---|---|

| Operator | ESA |

| COSPAR ID | 2010-013A |

| SATCAT № | 36508 |

| Website |

www |

| Mission duration | 3 years (planned) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | EADS Astrium |

| Launch mass | 720 kilograms (1,590 lb) |

| Dry mass | 684 kilograms (1,508 lb) |

| Dimensions | 4.6 by 2.3 metres (15.1 ft × 7.5 ft) |

| Power | 850 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 8 April 2010, 13:57:04 UTC[1] |

| Rocket | Dnepr |

| Launch site | Baikonur 109/95 |

| Contractor | ISC Kosmotras |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee | 718 kilometres (446 mi)[2] |

| Apogee | 732 kilometres (455 mi)[2] |

| Inclination | 92.03 degrees[2] |

| Period | 99.16 minutes[2] |

| Epoch | 24 January 2015, 20:44:24 UTC[2] |

| Transponders | |

| Band |

S Band (TT&C support) X Band (science data acquisition) |

| Bandwidth |

8kbit/s download (S Band) 100Mbit/s download (X Band) 2kbit/s upload (S Band) |

| Instruments | |

|

SIRAL: SAR Interferometer Radar Altimeter DORIS: Doppler Orbitography and Radiopositioning Integration by Satellite LRR: Laser Retroreflector | |

| |

CryoSat-2 is a European Space Agency environmental research satellite which was launched in April 2010. It provides scientists with data about the polar ice caps and tracks changes in the thickness of the ice with a resolution of about 1.3 centimetres (1⁄2 in).

CryoSat-2 was built as a replacement for CryoSat-1, whose Rokot carrier rocket was unable to achieve orbit, resulting in the loss of the satellite. Compared to its predecessor, CryoSat-2 features software upgrades, greater battery capacity and an updated instrument package. Its main instrument is an interferometric radar range-finder with twin antennas, which measures the height difference between the upper surface of floating ice and surrounding water. This is often known as 'free-board'.

CryoSat-2 is operated as part of the CryoSat programme to study the Earth's polar ice caps, which is itself part of the Living Planet programme. The CryoSat-2 spacecraft was constructed by EADS Astrium, and was launched by ISC Kosmotras, using a Dnepr carrier rocket, on 8 April 2010. On 22 October 2010, CryoSat-2 was declared operational following six months of on-orbit testing.[3]

Background

The initial proposal for the CryoSat programme was submitted as part of a call for proposals in July 1998 for Earth Explorer missions as part of the European Space Agency's Living Planet programme.[4][5] It was selected for further studies in 1999, and following completion of a feasibility study the mission was authorised. The construction phase began in 2001, and in 2002 EADS Astrium was awarded a contract to build the spacecraft. A contract was also signed with Eurockot, to conduct the launch of the satellite using a Rokot/Briz-KM carrier rocket.[4]

Construction of the original spacecraft was completed in August 2004. Following testing, the spacecraft was shipped to the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in Russia during August 2005 and arrived on 1 September.[6] The launch occurred from Site 133/3 on 8 October, however due to a missing command in the rocket's flight control system, the second stage engine did not shut down at the end of its planned burn, and instead the stage burned to depletion.[7] This prevented the second stage and Briz-KM from separating, and as a result the rocket failed to achieve orbit. The spacecraft was lost when it reentered over the Arctic Ocean, north of Greenland.[8][9]

Due to the importance of the CryoSat mission for understanding global warming and reductions in polar ice caps, a replacement satellite was proposed.[10][11] The development of CryoSat-2 was authorised in February 2006, less than five months after the failure.[12]

Development

Like its predecessor, CryoSat-2 was constructed by EADS Astrium, with its main instrument being built by Thales Alenia Space.[13] Construction and testing of the spacecraft's primary instrument was completed by February 2008, when it was shipped for integration with the rest of the spacecraft.[14] In August 2009, the spacecraft's ground infrastructure, which had been redesigned since the original mission, was declared ready for use.[15] Construction and testing of the spacecraft had been completed by mid-September.[16] The Project Manager for the CryoSat-2 mission was Richard Francis, who had been the Systems Manager on the original CryoSat mission.[17]

CryoSat-2 is an almost-identical copy of the original spacecraft,[18] however modifications were made including the addition of a backup radar altimeter.[16] In total, 85 improvements were made to the spacecraft when it was rebuilt.[19]

Supporting Measurements: CRYOVEX

It was clear from the beginning of the CryoSat programme that an extensive series of measurements would be needed, both to understand interaction of the radar waves with the surface of the ice caps and to relate the measured freeboard of floating sea ice with its thickness. This latter, in particular, would have to take account of snow loading. For sea ice, which moves as it is blown by the wind, it was also necessary to develop techniques which could give consistent results when measured from platforms travelling at different speed (scientists on the surface, helicopter-towed sounders, aircraft-borne radars and CryoSat itself). A number of campaigns were performed under a programme called CRYOVEX[19] which aimed to address each of the identified areas of uncertainty. These campaigns continued through the development of the original CryoSat and were planned to continue after its launch.

Following the announcement that CryoSat-2 would be built the CRYOVEX programme was extended. Experiments were conducted in Antarctica to determine how snow could affect its readings, and to provide data for calibrating the satellite.[20] In January 2007 the European Space Agency issued a request for proposals for further calibration and validation experiments.[21] Further CryoVEx experiments were conducted on Svalbard in 2007,[22] followed by a final expedition to Greenland and the Devon Ice Cap in 2008.[23] Additional snow measurements were provided by the Arctic Arc Expedition, and the Alfred Wegener Institute's Airborne Synthetic Aperture and Interferometric Radar Altimeter System (ASIRAS) instrument, mounted aboard a Dornier Do 228 aircraft.[22]

Final preparations

When it was approved in February 2006, the launch of CryoSat-2 was planned for March 2009.[12] It was originally planned that like its predecessor it would be launched by a Rokot,[24] however due to a lack of available launches a Dnepr rocket was selected instead. ISC Kosmotras were contracted to perform the launch.[25] Due to delays to earlier missions and range availability problems, the launch was delayed until February 2010.[26]

The Dnepr rocket assigned to launch CryoSat-2 arrived at the Baikonur Cosmodrome by train on 29 December 2009.[27] On 12 January 2010, the first two stages of the rocket were loaded into the launch canister, and the canister was prepared for transportation to the launch site.[28] On 14 January, it was rolled out to Site 109/95, where it was installed into its silo. The next day saw the third stage transported to the silo, and installed atop the rocket.[29]

Following the completion of its construction, CryoSat-2 was placed into storage to await launch.[16] In January 2010, the spacecraft was removed from storage, and shipped to Baikonur for launch. It departed Munich Franz Josef Strauss Airport aboard an Antonov An-124 aircraft on 12 January,[30] and arrived at Baikonur the next day.[30][31] Following arrival at the launch site, final assembly and testing were conducted.[32]

During final testing, engineers detected that the spacecraft's X band (NATO H/I/J bands) communications antenna was transmitting only a tiny fraction of the power that it should. Thermal imaging showed that the waveguide to the antenna, deep inside the spacecraft, was very hot. Clearly that was where the missing power was being dissipated. The waveguide could not normally be inspected or repaired without major disassembly of the satellite, which would have required a return to the facilities in Europe and resulted in a major delay to the launch. To avoid doing this, a local surgeon was brought in to inspect the component with an endoscope.[33] The surgeon, Tatiana Zykova,[34] discovered that two pieces of ferrite were lodged in the tube, and was able to remove both of them. Engineers were able to assist the removal of the second one with a magnet.[33] It was determined that the ferrite had come from an absorption load installed deep inside the antenna, which was intended to improve its performance. Some ferrite (the remaining stump of this load) was removed from inside the base of the antenna in order to prevent any further debris falling into the waveguide.[33]

On 4 February, the CryoSat-2 spacecraft was fuelled for launch. Then on 10 February it was attached to the payload adaptor, and encapsulated in the payload fairing,[35] to form a unit known as the Space Head Module.[32] This was transported to the launch pad by means of a vehicle known as the crocodile, and installed atop the carrier rocket.[36] Rollout occurred on 15 February, and the next day the satellite was activated in order to test its systems following integration onto the rocket.[35]

Launch

When the spacecraft was installed atop the Dnepr, launch was scheduled to occur on 25 February, at 13:57 UTC.[37] Prior to this, a practice countdown was scheduled for 19 February.[36] Several hours before the practice was scheduled to begin ISC Kosmotras announced that the launch had been delayed, and as a result the practice did not take place.[35] The delay was caused by a concern that the second stage manoeuvring engines did not have a sufficient quantity of reserve fuel.[38]

Following the delay, the Space Head Module was removed from the rocket, and returned to its integration building on 22 February.[35] Whilst it was in the integration building, daily inspections were made to ensure that the spacecraft was still functioning normally. Once the fuel issue had been resolved, the launch was rescheduled for 8 April, and launch operations resumed.[39] On 1 April, the Space Head Module was returned to the silo, and reinstalled atop the Dnepr. Following integrated tests, the practice countdown was successfully conducted on 6 April.[40]

CryoSat-2 was launched at 13:57:04 UTC on 8 April 2010.[1] Following a successful launch,[41] CryoSat-2 separated from the upper stage of the Dnepr into a low Earth orbit. The first signals from the satellite were detected by a ground station at the Broglio Space Centre in Malindi, Kenya, seventeen minutes after launch.[42]

Mission

CryoSat-2's mission is to study the Earth's polar ice caps,[43] measuring, and looking for variation in, the thickness of the ice. Its mission is identical to that of the original CryoSat.[42]

The primary instruments aboard CryoSat-2 are SIRAL-2,[14] the SAR/Interferometric Radar Altimeters;[19] which uses radar to determine and monitor the spacecraft's altitude in order to measure the elevation of the ice. Unlike the original CryoSat, two SIRAL instruments are installed aboard CryoSat-2, with one serving as a backup in case the other fails.[16]

A second instrument, Doppler Orbit and Radio Positioning Integration by Satellite, or DORIS, is used to calculate precisely the spacecraft's orbit.[44] An array of retroreflectors are also carried aboard the spacecraft, and allow measurements to be made from the ground to verify the orbital data provided by DORIS.[44][45]

Following launch, CryoSat-2 was placed into a low Earth orbit with a perigee of 720 kilometres (450 mi), an apogee of 732 kilometres (455 mi), 92 degrees of inclination and an orbital period of 99.2 minutes.[46] It had a mass at launch of 750 kilograms (1,650 lb),[24] and is expected to operate for at least three years.[45]

Launch and Early Orbit Phase operations were completed in the morning of 11 April 2010, and SIRAL-2 was activated later the same day.[47] At 14:40 UTC, the spacecraft returned its first scientific data.[48] Initial data on ice thickness was presented by the mission's Lead Investigator, Duncan Wingham, at the 2010 Living Planet Symposium on 1 July.[49] Later the same month, data was made available to scientists for the first time.[50] The spacecraft underwent six months of on-orbit testing and commissioning, which concluded with a review on 22 October 2010 that found the spacecraft was operating as expected, and that it was ready to begin operations.[51]

The exploitation phase of the mission started on the 26 October 2010 under the responsibility of Tommaso Parrinello who is currently the Mission Manager.

Results

The primary mission of Cryosat-2 is to measure ice thickness and hence volume. Previous satellites could only measure ice area and ice extent ( defined by the proporiton of sea surface which is covered with ice ).

The UK Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling ( CPOM ) [52] now provided near real time data products and maps of sea-ice thickness and volume. Graphs and maps are copyright and are available at source :

- Arctic sea-ice volume maps [53]

- graphs of monthly total Arctic sea-ice [54]

These measurements cannot be made accurately in the Arctic summer due to the presence of pools of melt water which cover significant areas of ice and which the satellite cannot distinguish from open water. For this reason the project does not provide data between May and September each year.

Data from CryoSat-2 has shown 25,000 seamounts, with more to come as data is interpreted.[55][56][57][58]

See also

- ESA's Living Planet Programme

- ICESat (NASA)

References

- 1 2 McDowell, Jonathan. "Launch Log". Jonathan's Space Page. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "CRYOSAT 2 Satellite details 2010-013A NORAD 36508". N2YO. 24 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "CryoSat-2 Earth Explorer Opportunity Mission-2". ESA eoPortal. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- 1 2 Wade, Mark. "Cryosat". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Coppinger, Rob (22 April 2010). "Cryosat: a decade long journey for industry". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "L-37". CryoSat Daily. Eurockot. 1 September 2005. Archived from the original on 11 March 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Zak, Anatoly. "Rockot". RussianSpaceWeb. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat Mission lost due to launch failure". European Space Agency. 8 October 2005. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat Mission has been lost". Eurockot. 8 October 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Cryosat team desperate to rebuild". BBC News. 10 October 2005. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (8 April 2010). "European ice-watching satellite will launch Thursday". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "ESA confirms CryoSat recovery mission". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 24 February 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat ready for launch: Media Day at IABG/Munich". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 4 September 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Major milestone reached in CryoSat-2 development". Living Planet Programme - CryoSat-2. European Space Agency. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Ground segment declared ready for CryoSat mission". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 de Selding, Peter B. (14 September 2009). "ESAs Cryosat 2 Faces Delay due to Launch Range Issues". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat-2 Project Manager: interview with Richard Francis". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (9 April 2010). "Cryosat-2 - A measure of Europe's ambition". BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 "CryoSat-2 on the road to recovery". Living Planet Programme - CryoSat-2. European Space Agency. 12 March 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Workshop on Antarctic sea-ice highlights need for CryoSat-2 mission". Living Planet Programme - CryoSat-2. European Space Agency. 9 August 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat-2 Announcement of Opportunity". Living Planet Programme - CryoSat-2. European Space Agency. 11 January 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Scientists and polar explorers brave the elements in support of CryoSat-2". Living Planet Programme - CryoSat-2. European Space Agency. 19 April 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Scientists endure Arctic for last campaign prior to CryoSat-2 launch". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 Krebs, Gunter. "Cryosat 1,2". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (8 April 2010). "Russian Dnepr rocket launches with CryoSat-2". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "February launch for ESA's CryoSat ice mission". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 14 September 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "На Байконур доставлена ракета РС-20". Russian Federal Space Agency. 30 December 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "На космодроме Байконуре начались работы по подготовке к пуску ракеты РС-20 с КА "КриоСат-2"". Russian Federal Space Agency. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "На Байконуре готовятся к пуску "КриоСат-2"". Russian Federal Space Agency. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "CryoSat-2 – the icy mission is hotting up". EADS Astrium. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "На космодром Байконур доставлен космический аппарат КриоСат-2". Russian Federal Space Agency. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Entry 3: Important milestone passed". CryoSat Launch Diary. European Space Agency. 12 February 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Entry 2: CryoSat-2 undergoes surgery". CryoSat Launch Diary. European Space Agency. 29 January 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Entry 2: CryoSat-2 undergoes surgery - images". CryoSat Launch Diary. European Space Agency. 29 January 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Jäger, Klaus; Paul, Edmund. "Cryosat-2 Activities in February". EADS Astrium. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Entry 4: Crocodile to the silo". CryoSat Launch Diary. European Space Agency. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Last look at CryoSat-2". Observing the Earth. European Space Agency. 11 February 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Entry 5: Launch delayed". CryoSat Launch Diary. European Space Agency. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Entry 7: Launch campaign resumes". CryoSat Launch Diary. European Space Agency. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Jäger, Klaus; Paul, Edmund. "Cryosat-2 Blog, live from Kazakhstan". EADS Astrium. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Jones, Tamera (8 April 2010). "Successful launch for ESA's CryoSat-2 ice mission". Natural Environment Research Council. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Successful launch for ESA's CryoSat-2 ice satellite". Permanent Mission in Russia. European Space Agency. 8 April 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat: an icy mission". European Space Agency. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "ILRS Mission Support". CryoSat. NASA International Laser Ranging Service. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Cryosat". NASA International Laser Ranging Service. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CRYOSAT 2 Satellite details". Real Time Satellite Tracking. N2YO.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (12 April 2010). "Esa's Cryosat mission switches on radar instrument". BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "ESA's ice mission delivers first data". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 13 April 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "CryoSat-2 exceeding expectations". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 1 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "Scientists receive first CryoSat-2 data". CryoSat. European Space Agency. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (27 October 2010). "CryoSat 2 passes in-orbit tests with flying colors". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ↑ http://cpom.leeds.ac.uk/

- ↑ http://www.cpom.ucl.ac.uk/csopr/seaice.html?%20show_cell_thk_ts_large=0&ts_area_or_point=all&basin_selected=0&show_basin_thickness=0&thk_period=0&year=2014&season=Autumn&select_thk_vol=select_vol

- ↑ http://www.cpom.ucl.ac.uk/csopr/seaice.html?show_cell_thk_ts_large=1&ts_area_or_point=all&basin_selected=0&show_basin_thickness=0&thk_period=0&select_thk_vol=select_vol&year=2014&season=Autumn

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan. "Satellites detect 'thousands' of new ocean-bottom mountains" BBC News, 2 October 2014.

- ↑ "New Map Exposes Previously Unseen Details of Seafloor"

- ↑ David T. Sandwell, R. Dietmar Müller, Walter H. F. Smith, Emmanuel Garcia, Richard Francis. "New global marine gravity model from CryoSat-2 and Jason-1 reveals buried tectonic structure" Science 3 October 2014: Vol. 346 no. 6205 pp. 65-67. DOI: 10.1126/science.1258213

- ↑ "Cryosat 4 Plus" DTU Space